1 Private William Charles Norman, Number 669305 of the 3 Battalion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRINITY COLLEGE Cambridge Trinity College Cambridge College Trinity Annual Record Annual

2016 TRINITY COLLEGE cambridge trinity college cambridge annual record annual record 2016 Trinity College Cambridge Annual Record 2015–2016 Trinity College Cambridge CB2 1TQ Telephone: 01223 338400 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.trin.cam.ac.uk Contents 5 Editorial 11 Commemoration 12 Chapel Address 15 The Health of the College 18 The Master’s Response on Behalf of the College 25 Alumni Relations & Development 26 Alumni Relations and Associations 37 Dining Privileges 38 Annual Gatherings 39 Alumni Achievements CONTENTS 44 Donations to the College Library 47 College Activities 48 First & Third Trinity Boat Club 53 Field Clubs 71 Students’ Union and Societies 80 College Choir 83 Features 84 Hermes 86 Inside a Pirate’s Cookbook 93 “… Through a Glass Darkly…” 102 Robert Smith, John Harrison, and a College Clock 109 ‘We need to talk about Erskine’ 117 My time as advisor to the BBC’s War and Peace TRINITY ANNUAL RECORD 2016 | 3 123 Fellows, Staff, and Students 124 The Master and Fellows 139 Appointments and Distinctions 141 In Memoriam 155 A Ninetieth Birthday Speech 158 An Eightieth Birthday Speech 167 College Notes 181 The Register 182 In Memoriam 186 Addresses wanted CONTENTS TRINITY ANNUAL RECORD 2016 | 4 Editorial It is with some trepidation that I step into Boyd Hilton’s shoes and take on the editorship of this journal. He managed the transition to ‘glossy’ with flair and panache. As historian of the College and sometime holder of many of its working offices, he also brought a knowledge of its past and an understanding of its mysteries that I am unable to match. -

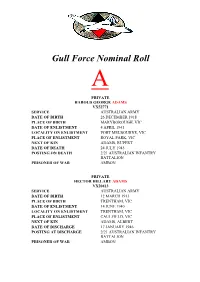

Nominal Roll A

Gull Force Nominal Roll A PRIVATE HAROLD GEORGE ADAMS VX52771 SERVICE AUSTRALIAN ARMY DATE OF BIRTH 26 DECEMBER 1918 PLACE OF BIRTH MARYBOROUGH, VIC DATE OF ENLISTMENT 4 APRIL 1941 LOCALITY ON ENLISTMENT PORT MELBOURNE, VIC PLACE OF ENLISTMENT ROYAL PARK, VIC NEXT OF KIN ADAMS, RUPERT DATE OF DEATH 24 JULY 1945 POSTING ON DEATH 2/21 AUSTRALIAN INFANTRY BATTALION PRISONER OF WAR AMBON PRIVATE HECTOR HILLARY ADAMS VX20413 SERVICE AUSTRALIAN ARMY DATE OF BIRTH 12 MARCH 1913 PLACE OF BIRTH TRENTHAM, VIC DATE OF ENLISTMENT 14 JUNE 1940 LOCALITY ON ENLISTMENT TRENTHAM, VIC PLACE OF ENLISTMENT CAULFIELD, VIC NEXT OF KIN ADAMS, ALBERT DATE OF DISCHARGE 17 JANUARY 1946 POSTING AT DISCHARGE 2/21 AUSTRALIAN INFANTRY BATTALION PRISONER OF WAR AMBON PRIVATE JAMES WILLIAM ADAMS VX39777 SERVICE AUSTRALIAN ARMY DATE OF BIRTH 1 MARCH 1919 PLACE OF BIRTH ALBERT PARK, VIC DATE OF ENLISTMENT 18 FEBRUARY 1941 LOCALITY ON ENLISTMENT ALBERT PARK, VIC PLACE OF ENLISTMENT ROYAL PARK, VIC NEXT OF KIN ADAMS, WILLIAM DATE OF DEATH 1 OCTOBER 1945 POSTING ON DEATH 2/21 AUSTRALIAN INFANTRY BATTALION PRISONER OF WAR AMBON/HAINAN PRIVATE ROBERT GEORGE ADAMS VX24928 SERVICE AUSTRALIAN ARMY DATE OF BIRTH 12 OCTOBER 1919 PLACE OF BIRTH HAWTHORN, VIC DATE OF ENLISTMENT 10 JUNE 1940 LOCALITY ON ENLISTMENT EAST KEW, VIC PLACE OF ENLISTMENT CAULFIELD, VIC NEXT OF KIN ADAMS, ROBERT DATE OF DEATH 20 FEBRUARY 1942 POSTING ON DEATH 2/21 AUSTRALIAN INFANTRY BATTALION PRISONER OF WAR LAHA PRIVATE KENNETH RANDALL ADAMSON WX9564 SERVICE AUSTRALIAN ARMY DATE OF BIRTH 5 FEBRUARY 1913 -

Table of Contents

The Proceedings of the Cambridge Historical Society, Volume 28, 1942 TABLE OF CONTENTS PROCEEDINGS ONE HUNDRED THIRTY-NINTH MEETING................................................................5 ONE HUNDRED FORTIETH MEETING.....................................................................7 ONE HUNDRED FORTY-FIRST MEETING................................................................8 ONE HUNDRED FORTY-SECOND MEETING..........................................................9 PAPERS THOMAS FULLER AND HIS DESCENDANTS.............................................................11 BY ARTHUR B. NICHOLS THE WYETH BACKGROUND.......................................................................................... 29 BY ROGER GILMAN ALL ABOARD THE "NATWYETHUM"............................................................................... 35 BY SAMUEL ATKINS ELIOT LONGFELLOW AND DICKENS........................................................................................ 55 THE STORY OF A TRANS-ATLANTIC FRIENDSHIP BY HENRY WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW DANA LOIS LILLEY HOWE'S INTRODUCTION TO THE CENTENARY OF THE CAMBRIDGE BOOK CLUB............................................................................................. 105 THE CENTENARY OF THE CAMBRIDGE BOOK CLUB.............................................. 109 BY FRANCIS GREENWOOD PEABODY ANNUAL REPORTS......................................................................... 121 MEMBERS....................................................................................... 125 THE CAMBRIDGE -

Administration of Barack H. Obama, 2009 Digest of Other White House Announcements December 31, 2009 January 20 January 21 Januar

Administration of Barack H. Obama, 2009 Digest of Other White House Announcements December 31, 2009 The following list includes the President's public schedule and other items of general interest announced by the Office of the Press Secretary and not included elsewhere in this Compilation. January 20 In the afternoon, in Statuary Hall at the U.S. Capitol, the President and Mrs. Obama participated in the Inaugural luncheon. Later, they attended the Inaugural parade. In the evening, at the Washington Convention Center, the President and Mrs. Obama attended and made remarks at the Neighborhood Ball. During the ball, he participated in an interview with Robin Roberts of ABC News. They then attended and made remarks at the Obama Home State Ball. Later in the evening, at the National Building Museum, the President and Mrs. Obama attended and made remarks at the Commander-in-Chief Ball. Then, at the Hilton Washington Hotel Center, they attended and made remarks at the Youth Ball. Later, at the Washington Convention Center, they attended and made remarks at the Biden Home State Ball followed by the Mid Atlantic Region Ball. January 21 In the morning, at the Washington Convention Center, the President and Mrs. Obama attended and made remarks at the West/Southwestern Regional Ball followed by the Midwestern Regional Ball. Later, at the DC Armory, they attended and made remarks at the Southern Regional Ball. Then, at Union Station, they attended and made remarks at the Eastern Regional Ball. Later in the morning, the President met with White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel. -

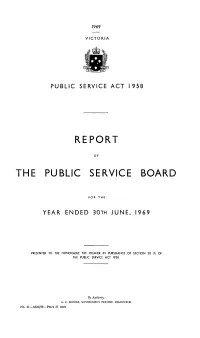

Report the Public Service Board

1969 VICTORIA PUBLIC SERVICE ACT 1958 REPORT OF THE PUBLIC SERVICE BOARD FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE, 1969 PRESENTED TO THE HONORABLE THE PREMIER IN PURSUANCE OF SECTION 20 (1) OF THE PUBLIC SERVICE ACT 1958 By Authority: A. C. BROOKS, GOVERNMENT PRINTER, MELBOURNE. No. 21.-6424/69.-PRICE 45 rents To the Honorable the Premier of Victoria. I furnish for submission to His Excellency the Governor in Council, as required by Section 20 of the Public Service Act 1958, the Annual Report on the Public Service for the year ended 30th June, 1969. F. E. CAHILL, Chairman, Public Service Board. 3rd December, 1969 CONTENTS SECTION PAGE Recruitment 7 2 The Service 8 3 Training 10 4 Staffing, Classification and Claims 12 5 Organization and Methods 15 6 Electronic Data Processing 18 7 Accommodation and Working Conditions 19 APPENDICES- ·• A" Number of Officers and Employees in the Various Departments and Salaries and Wages Paid 21 ,, B" Number of Permanent Officers in Each Division in the Various Departments .. 23 . c, Number of Males and Females (Permanent and Temporary) Employed in the Various Departments 23 D" Number of Officers in each Class of the Administrative and Professional Divisions in the Various Departments 24 "E" Recruitment of Staff 25 "F" Overtime and Penalty Rate Payments 26 "G" Appeals re Promotions 27 "H" Long Service Leave Applications 27 "I" Officers Sent Abroad 28 "J" Charges Referred to the Board 30 "K" Claims by Approved Associations 31 "L" Courses and Conferences Conducted by Departments 32 "M" Officers, Emp1oyees or Persons or Classes of Officers, Employees or Persons to Whom the Provisions of the Public Service Acts have been Declared not to Apply under Section 4 (1) (k) . -

1924 Totem.Pdf

‘ c:s:,-d0.;--:;;‘ ‘(5he Ninth Annual oJD ‘Uhe University of British Columbia DEDICATION To the memory of a staunch friend of this University’ DR. S. D. SCOTT, M.A., LL.D., for ten years Honorary Secretary of the Board of Governors, this Annual is respectfully” dedicated. — I ‘The University of British Columbia VANCOUVER, B. C. — President—LEONARD S. KLINCK, B.S.A. (Torcnto), M.S.A., D.Sc. (Iowa State College) FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCE Dean: H. T. J. COLEMAN, B.A. (Toronto), Ph.D. (Columbia). The courses in Arts and Science leading to the degrees of B.A. and M.A. embrace English literature, Classical literature, Modern Languages, History, Philosophy, the Principles of Economics and Government, Chemistry. Mathematics, Physics, Biology, Bacteriology and allied subjects. At the request of the Provincial Department of Education, courses in Education leading to the Academic Certificate are given in the faculty of Arts and Science. These courses are open to University Graduates only. FACULTY OF APPLIED SCIENCE Dean: REGINALD W. BROCK, M.A., LL.D. (Queen’s), F.G.S., F.R.S.C. Courses leading to the degrees of B.A.Sc. and M.A.Sc. are offered in Chemical Engineering, Chemistry, Civil Engineering, Forest Engineering, Geological Engineering, Mechanical Engineering, Metallurgical Engineering, Mining Engineering, Nursing and Public Health. FACULTY OF AGRICULTURE Dean: F. M. CLEMENT, B.S.A. (Toronto), M.A. (Wisconsin). The courses in Agriculture leading to the degrees of B.S.A. and M.S.A. include the departments of Agronomy, Animal Husbandry, Horticulture, Dairying, Poultry Husbandry, and subjects connected therewith. -

12414. Supplement to the London Gazette, 7 Octobek, 1.919

12414. SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 7 OCTOBEK, 1.919, Decorations conferred by M2/177581 Private George . Porter, 654th Mechanical Transport Depot, Royal Army HIS MAJESTY. THE KING OF ITALY. .'Service Corps (Carnoustie, Forfar). Order of St. Maurice and St. Lazarus. Officer. Brevet Colonel (Colonel in Army) Charles Anthony Lamb, C.M.G., M.V.O., Retired Decorations conferred by Pay, late Military Attache. THE PRESIDENT OF THE PORTU- Cavalier. GUESE REPUBLIC. Temporary Major Anthony Mario Caccia, Special List. Military Order of A viz. Grand Officer. Order of the Crown of Italy. Major-General Edwin Henry de Vere Atkin- Grand Officer. son, C.B., C.M.G., C.I.E. Major-General The Honourable Charles John Major-General John Joseph Gerrard, C.B., Sackville-West, K.B.E., C.M.G. C.M.G., M.B. Colonel (Honorary Brigadier-General) Gerald Commander. Hedley Ovens, C.B. (retired pay). Lieutenant-Colonel and Brevet Colonel (tempo- Colonel (temporary Brigadier-General) Henry rary Brigadier-General) Herbert William . Osman Vincent, C.B., O.M.G. Studd, C.B,, C.M.G., D.S.O., Coldstream Guards. .' ' Commander..' Major {temporary Brigadier-General). Chris- Major John Humphrey Barb our,. Jtf.B., Royal topher Birdwopd Thomson, C.B'.E.., V.S.O., Army JSEedical Corps. Bjoyal Engineers. Temporary Lieutenant (acting Major) Harold Major and Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel (tempo- Kenyon Benn, Royal Army'Ordnance Corps. rary Brigadier-General) Sir Hereward Lieutenant-Colonel and Brevet Colonel Henry W;ake, Bt., C.M.G., D.S.O., King's Royal Lawrence Norman Beynon, C.M.G., Royal 'Rifle Corps. Garrison Artillery. -

Charles G. Dawes Archive

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections Northwestern University Library, Evanston, Illinois 60208-2300 Charles G. Dawes Archive Biography: Charles Gates Dawes (1865-1951), prominent in U.S. politics and business, served as Comptroller of the Currency (1898-1901), director of the Military Board of Allied Supply (1918-1919), and first director of the Bureau of the Budget (1921). He received a Nobel Peace Prize as chairman of the Reparations Commission which restructured Germany's economy and devised a repayment plan (1924). He was elected Vice-President (1925- 1929), and appointed ambassador to England (1929-1931) and chairman of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (1932). Charles and his brothers founded Dawes Brothers Incorporated. Dawes formed the Central Trust Co. in Chicago (1902), guided its successor banks, and was influential in Chicago business, politics, and philanthropy until his death. Charles Gates Dawes was born and educated in Ohio. He married Caro Blymyer in 1889, practiced law, and incorporated a real estate business in Lincoln, Nebraska, before moving to Evanston, Illinois in 1895. He acquired utility companies and real estate in northern Illinois and Wisconsin; and in 1908, with his brothers Henry, Rufus, and Beman, formed Dawes Brothers Incorporated, to invest assets in banks, oil companies and real estate throughout the country. Various acquaintances who were prominent in political and industrial affairs trusted them to manage their investments as well. Other companies in which Charles Dawes and his brothers played leading roles included Chicago's Central Trust Co. and its successor banks and Pure Oil Company of Ohio. Dawes made significant philanthropic contributions to the Chicago metropolitan community. -

Point of Failure: British Army Brigadiers in the British Expeditionary Force and North Western Expeditionary Force, 1940 a Study of Advancement and Promotion

POINT OF FAILURE: BRITISH ARMY BRIGADIERS IN THE BRITISH EXPEDITIONARY FORCE AND NORTH WESTERN EXPEDITIONARY FORCE, 1940 A STUDY OF ADVANCEMENT AND PROMOTION - PHILIP MC CARTY MA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Wolverhampton for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2021 This work or any part thereof has not been previously presented in any form to the University or to any other body whether for the purposes of assessment, publication or for any other purpose (unless otherwise indicated). Save for any express acknowledgements, references and/or biographies cited in the work, I confirm that the intellectual content of the work is the result of my own efforts and of no other person. The right of Philip Mc Carty to be identified as author of this work is asserted in accordance with ss.77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. At this date copyright is owned by the author. POINT OF FAILURE PJ MC CARTY – UNIVERSITY OF WOLVERHAMPTON ABSTRACT By the summer of 1940 the British Army had suffered two simultaneous strategic defeats in Norway and France. Both had led to hurried and ignominious evacuations. A popular misconception contends that this led to a wholesale clearing out of the British Army’s command structure in order to start again, and that many officers suffered the loss of their careers in the necessity to rebuild an army both to withstand invasion and enable victory over Nazi Germany. This thesis contends that this belief is misplaced, and that rather than automatically ending the careers of all involved, some officers would progress and even thrive after 1940 in varying degrees. -

2018 Conference Schedule.Pmd

The American Veterans Center’s 21st Annual Veterans Conference & American Valor: A Salute to Our Heroes October 25-27, 2018 - Washington, DC Locations of Events: ‘The Wounded Warrior Experience’ ‘An Evening Reception & Conference Speaker Sessions Honoring Our Veterans’ The National Archives Friday Evening Reception - October 26 William G. McGowan Theater The Royal Norwegian Embassy 700 Pennsylvania Ave., NW Ambassador’s Residence Washington, DC 20408 3401 Massachusetts Ave, Washington, DC 20007 Business Attire ‘American Valor: A Salute to Our Heroes’ Omni Shoreham Hotel 2500 Calvert St. NW Washington, DC 20008 Black Tie Attire Visit www.americanveteranscenter.org for information on registration and special discounted rates at The Omni Shoreham Hotel. Schedule of Events: Times & Topics subject to change - Additional Speakers & Participants TBA Visit www.americanveteranscenter.org for continued updates and additions Thursday, October 25 6:30 PM - “The Wounded Warrior Experience” William G. McGowan Theater - The National Archives Presented by Military Order of the Purple Heart Service Foundation Featuring service members who have been wounded in the line of duty, sharing their inspiring stories of recovery and determination, along with resources available to service members transitioning from the military to the private sector. Featuring: Staff Sergeant Robert Bartlett - U.S. Army scout sniper, wounded by an Iranian-designed Explosively Formed Penetrator (EFP) while serving in Iraq, 2005. HM2 Joshua Chiarini - U.S. Navy Corpsman awarded the Silver Star and wounded in action saving Marines on combat patrol in Iraq, 2006. Jim Martinson - Veteran of Vietnam who lost both legs to a landmine, has since become an avid skier, snowboarder, and golfer; representing Military Order of the Purple Heart. -

Aberdeen Propinquity Book 1706

CA/5/10/2 Aberdeen Burgh Propinquity Book (CA/5/10/2) Volume 2 – 1706 – 1746 Directory of Cases 1. Date: 4th [?] 1706 Case: Ship “Eagle” of Aberdeen, sailing from Livorno to Leith or Aberdeen, commanded by Alexander Midleton. [See also entries 2, 3, 4, 8 Deponents: Alexander Midleton* (commander), Alexander Ffleming (mate), James Robertson (carpenter), Robert Bannerman (carpenter’s mate), George Milne (surgeon). Statement: The ship was attacked and taken on 1st April 1706 by the French privateer “Prince of Contie[?]” from Saint Mallas [St Malo?]. Alexander Midleton paid ransom and left hostages Patrick Bannerman, merchant in Aberdeen, and John Burnett, apprentice in London. The “Eagle” was delayed in her journey by bad weather and damaged cargo. In Dublin most of the crew were pressed into service in the English fleet. The “Eagle” could not proceed further and Alexander Midleton had to sell the cargo in Dublin. List of goods pillaged by the privateers. *Signature: Middleton 2. Date: 4th [?] 1706 Case: Ship “Eagle” of Aberdeen, sailing from Livorno to Leith or Aberdeen, commanded by Alexander Midleton. [See also entries 1, 3, 4, 8 Deponent: John Gordon, merchant in Aberdeen, on his own behalf and that of his company. Statement: Declaration of insurance on cargo. 3. Date: 4th [?] 1706 Case: Ship “Eagle” of Aberdeen, sailing from Livorno to Leith or Aberdeen, commanded by Alexander Midleton. [See also entries 1, 2, 4, 8 Deponent: Alexander Midleton, master of the “Eagle”. Statement: List of goods on board belonging to himself and declaration of loss by pillage. 4. Date: 4th [?] 1706 Case: Ship “Eagle” of Aberdeen, sailing from Livorno to Leith or Aberdeen, commanded by Alexander Midleton. -

Norman Cousins Papers, 1924-1991, Bulk 1944-1990

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft558004w3 No online items Finding Aid for the Norman Cousins papers, 1924-1991, bulk 1944-1990 Processed by Manuscripts Division staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Norman 1385 1 Cousins papers, 1924-1991, bulk 1944-1990 Finding Aid for the Norman Cousins Papers, 1924-1991, bulk 1944-1990 Collection number: 1385 UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Los Angeles, CA Contact Information Manuscripts Division UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Telephone: 310/825-4988 (10:00 a.m. - 4:45 p.m., Pacific Time) Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ Processed by: Manuscripts Division staff Encoded by: Caroline Cubé Text converted and initial container list EAD tagging in part by: Apex Data Services © 2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Norman Cousins papers, Date (inclusive): 1924-1991, bulk 1944-1990 Collection number: 1385 Creator: Cousins, Norman. Extent: 1816 boxes (908 linear ft.) Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Department of Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection.