Form and Function of Third-Party Politeness in Cicero Risselada, R.; Van Gils, L.W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abkürzungsverzeichnis

625 Abkrzungsverzeichnis Quellen – Quelleneditionen – Zeitschriften und Sammelwerke Quellen Ach. Tat. Achilleus Tatios Acta Acta Apostolorum Aet. Aetios Ail. takt. Ailianos, Taktika Ain. Takt. Aineias Taktikos Aischyl. Prom. Aischylos, Prometheus Aischyl. Agam. Aischylos, Agamemnon Alk. Alkaios Amm. Ammianus Marcellinus Anaxandr. Anaxandros, Fragmente Anaximen. rhet. Alex. Anaximenes, Rhetorica ad Alexandrum Anon. Peripl. mar. Erythr. Anonymus, Periplus maris Erythraei Apoll. Rhod. Argon. Apollonios Rhodios, Argonautika Apollod. Apollodoros, Bibliotheke App. civ. Appianos, Bella civilia App. Ill. Appianos, Illyrica App. Mithr. Appianos, Mithridatius App. Pun. Appianos, Punica App. Samn. Appianos, Samnitica App. Syr. Appianos, Syriaca Apuleius, Metamorph. Apuleius, Metamorphosen Archim. Archimedes Aristeid. panath. Aristeides, Panathenaikos Aristid. Or. Ailios Aristeides, Oratores Aristoph. Ach. Aristophanes, Acharnenses Aristoph. Lys. Aristophanes, Lysistrata Aristoph. Nub. Aristophanes, Nubes Aristoph. Pax Aristophanes, Pax Aristot. an. post. Aristoteles, Analytica posteriora Aristot. Ath. pol. Aristoteles, Athenaion politeia Aristot. cael. Aristoteles, De caelo Aristot. hist. an. Aristoteles, Historia animalium Aristot. metaph. Aristoteles, Metaphysica Aristot. meteor. Aristoteles, Meterologica Aristot. Nikom. Ethik Aristoteles, Nikomachische Ethik Aristot. part. an. Aristoteles, De partibus animalium Aristot. phys. Aristoteles, Physica Aristot. pol. Aristoteles, Politica Aristot. probl. Aristoteles, Problemata Abkrzungsverzeichnis – -

Thesis Draft 3.23.2014.Docx

Cicero and Caesar: A Turbulent Amicitia by Adam L. Parison June, 2014 Director of Thesis/Dissertation: Dr. Frank E. Romer Major Department: History Though some study into the relationship between Cicero and Caesar has occurred, it is relatively little and the subject warrants more consideration. This is a significant gap in the historiography of late republican history. This thesis examines and attempts to define their relationship as a public amicitia. By looking at the letters of Cicero, his three Caesarian speeches, and his philosophical dialogue de Amicitia, I show that the amicitia between these two men was formed and maintained as a working relationship for their own political benefit, as each had something to gain from the other. Cicero’s extant letters encompass a little more than the last twenty years of Cicero’s life, when some of the most important events in Roman history were occurring. In this thesis, I examine selected letters from three collections, ad Quintum fratrem, ad Familiares, and ad Atticum for clues relating to Caesar’s amicitia with Cicero. These letters reveal the tumultuous path that the amicitia between Cicero and Caesar took over the years of the mid-50s until Caesar’s death, and , surprisingly, show Cicero’s inability to choose a side during the Civil War and feel confident in that choice. After Caesar’s victory at Pharsalus in 48, the letters reveal that Cicero hoped that Caesar could or would restore the republic, and that as time passed, he became less optimistic about Caesar and his government, but still maintained the public face of amicitia with Caesar. -

(2018) 57-72 an Ancient Example of Literary Blackmail?

AN ANCIENT EXAMPLE OF LITERARY BLACKMAIL ? C Coetzee ( Stellenbosch University ) Towards the end of his life and especially after his exile in 58 - 57 BC , Cicero’s publication program accelerated. While he aimed to promote his own glory, he had to do so in an environment where writing about oneself attracted censure. This article explores some of the ways in which Cicero tries to overcome this limitation. These include writing about himself indirectly, defending artists in court, soliciting historians to include his role as consul in their works and even attempts at public literary blackmail, specifically towards his prolific contemporary, Marcus Terentius Varro. Keywords : Cicero ; Varro ; De l egibus ; Pro Archia ; Academica ; publication ; glory . B y the time of the composition of his De f inibus in 45 BC , Cicero was very much aware that his publishing activity constituted a major achievement. Answering to the criticism that he focused too much on philosophy 1 and taking those to task who would discriminate against their own language, Cicero states in the prologue that those who would prefer him ‘to write upon other subjects may fairly be indulgent to one wh o has written much already — in fact no one of our nation more — and who perhaps will write still more if his life be prolonged’ ( 1 . 4 .11) . 2 We see the same sentiment expressed with rather more Ciceronian fire in letter 281, written to Atticus on 9 May of t he same year . Answering to the criticism of his continued mourning for the death of his daughter , 3 Cicero rages that ‘these happy folk who take me to task cannot read as many pages as I have written ’. -

Sallust's Histories and Triumviral Historiography

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Sallust's Histories and Triumviral Historiography Jennifer Gerrish University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Gerrish, Jennifer, "Sallust's Histories and Triumviral Historiography" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 511. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/511 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/511 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sallust's Histories and Triumviral Historiography Abstract This dissertation explores echoes of the triumviral period in Sallust's Histories and demonstrates how, through analogical historiography, Sallust presents himself as a new type of historian whose "exempla" are flawed and morally ambiguous, and who rejects the notion of a triumphant, ascendant Rome perpetuated by the triumvirs. Just as Sallust's unusual prose style is calculated to shake his reader out of complacency and force critical engagement with the reading process, his analogical historiography requires the reader to work through multiple layers of interpretation to reach the core arguments. In the De Legibus, Cicero lamented the lack of great Roman historians, and frequently implied that he might take up the task himself. He had a clear sense of what history ought to be : encomiastic and exemplary, reflecting a conception of Roman history as a triumphant story populated by glorious protagonists. In Sallust's view, however, the novel political circumstances of the triumviral period called for a new type of historiography. To create a portrait of moral clarity is, Sallust suggests, ineffective, because Romans have been too corrupted by ambitio and avaritia to follow the good examples of the past. -

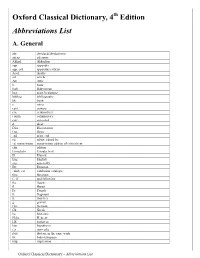

Abbreviations List A

Oxford Classical Dictionary, 4th Edition Abbreviations List A. General abr. abridged/abridgement adesp. adespota Akkad. Akkadian app. appendix app. crit. apparatus criticus Aeol. Aeolic art. article Att. Attic b. born Bab. Babylonian beg. at/nr. beginning bibliog. bibliography bk. book c. circa cent. century cm. centimetre/s comm. commentary corr. corrected d. died Diss. Dissertation Dor. Doric end at/nr. end ed. editor, edited by ed. maior/minor major/minor edition of critical text edn. edition Einzelschr. Einzelschrift El. Elamite Eng. English esp. especially Etr. Etruscan exhib. cat. exhibition catalogue fem. feminine f., ff. and following fig. figure fl. floruit Fr. French fr. fragment ft. foot/feet g. gram/s Ger. German Gk. Greek ha. hectare/s Hebr. Hebrew HS sesterces hyp. hypothesis i.a. inter alia ibid. ibidem, in the same work IE Indo-European imp. impression Oxford Classical Dictionary – Abbreviations List in. inch/es introd. introduction Ion. Ionic It. Italian kg. kilogram/s km. kilometre/s lb. pound/s l., ll. line, lines lit. literally lt. litre/s L. Linnaeus Lat. Latin m. metre/s masc. masculine mi. mile/s ml. millilitre/s mod. modern MS(S) manuscript(s) Mt. Mount n., nn. note, notes n.d. no date neut. neuter no. number ns new series NT New Testament OE Old English Ol. Olympiad ON Old Norse OP Old Persian orig. original (e.g. Ger./Fr. orig. [edn.]) OT Old Testament oz. ounce/s p.a. per annum PIE Proto-Indo-European pl. plate plur. plural pref. preface Proc. Proceedings prol. prologue ps.- pseudo- Pt. part ref. reference repr. -

Occupations and Attitudes Towards Them in the Late Roman Republic: Some Studies in the Literary Evidence

THE ‘SORDID’ OCCUPATIONS AND ATTITUDES TOWARDS THEM IN THE LATE ROMAN REPUBLIC: SOME STUDIES IN THE LITERARY EVIDENCE Laura K. Hickey BApp.Fin. BEc. (Macquarie University) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Research Department of Ancient History, Faculty of Arts Macquarie University, Sydney January, 2016 For my parents ii Table of Contents SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................ v DECLARATION .................................................................................................................. vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................. vii CHAPTER ONE .................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction and Literature Review ........................................................................................................................................ 1 Studies on servile and lower class occupations in Ciceronian Rome ...................................................................... 2 Approaches to the Study of Roman Occupations ............................................................................................................. 5 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................................................................... 11 Method -

Bibliography

Bibliography Abbreviations ASDErasmioperaomnia, Amsterdam, 1969–. CAH2 The Cambridge AncientHistory,2nd ed., Cambridge, 1984–2005. CIL Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum,Berlin, 1863–. DIVO Elisa Guadagnini and Giulio Vaccaro, Dizionario dei volgarizzamenti,http://tlion. sns.it/divo/. Eph.Tull. Ephemerides Tullianae,https://www.tulliana.eu/ephemerides/frames.htm. FRHist Timothy Cornell(ed.), The Fragments of the Roman Historians,Oxford, 2013. FRP Adrian S. Hollis (ed.), Fragments of Roman Poetry.c.60BC–AD 20,Oxford,2009. GL Heinrich Keil (ed.), Grammatici Latini,Leipzig, 1857–1880. LB JeanLeClerc(ed.), Desiderii Erasmi Operaomnia,Leiden, 1703–1706. MRR T. RobertS.Broughton, The Magistrates of the Roman Republic,New York, 1951– 1952 (Supplement1986 supersedes Suppl. 1960). OLD2 Peter G.W.Glare(ed.), Oxford Latin Dictionary, 2nd ed., Oxford2012. ORF4 EnricaMalcovati (ed.), Oratorum Romanorum fragmenta,4th ed., Torino 1976. Throughout this volume, references to ancient works aregiven according to the abbreviations of the OxfordClassical Dictionary. ForRenaissanceauthors,weused the abbreviations of Johann Ramminger’swebsite Neulateinische Wortliste. Ein Wörterbuch des Lateinischen von Petrarca bis 1700 (http://www.neulatein.de/words/start.htm). Workscited Abbot 2000: James C. Abbot, The Aeneid and the Conceptofdolus bonus,in: “Vergilius” 46, 59–82. Achard 1981: Guy Achard, Pratique rhétorique et idéologie politique dans les discours ‘optimates’ de Cicéron,Leiden. Ahl1976: Frederik M. Ahl, Lucan. An Introduction,Ithaca/London. vonAlbrecht 2003: Michael von Albrecht, Cicero’sStyle.ASynopsis. Followed by Selected Analytic Studies,Leiden/Boston. Alfonsi 1975: Luigi Alfonsi, Dal proemio del De inventione alle virtutes del De officiis,in: “Ciceroniana” 2, 111–120. Allen 1906–1958: Percy Stafford Allen et al. (eds.), Opus epistolarum Des. Erasmi Roterodami,Oxford. -

Download Download

«Ciceroniana on line» III, 1, 2019, 15-48 RAIJA VAINIO, REIMA VÄLIMÄKI, ALEKSI VESANTO, ANNI HELLA, FILIP GINTER, MARJO KAARTINEN, TEEMU IMMONEN1 RECONSIDERING AUTHORSHIP IN THE CICERONIAN CORPUS THROUGH COMPUTATIONAL AUTHORSHIP ATTRIBUTION The authorship of some texts related to Cicero or traditionally at- tributed to him has puzzled scholars for centuries. The most famous of these texts is Rhetorica ad C. Herennium, whose removal from the Cice- ronian corpus was proposed as early as the fifteenth century. The other two (minor) texts are Commentariolum petitionis, usually attributed to Marcus Cicero’s younger brother Quintus, and most recently De optimo genere oratorum. Sir Ronald Syme stated on the authenticity of old texts: «In every age the principal criteria of authenticity are the stylis- tic and the historical. They do not always bring certainty, for we do not know enough about either style or history. If a different approach can be devised, or a subsidiary method, so much the better»2. In recent years, digital methods have offered promising results for the reattribu- tion of classical texts. M. Kestemont, J.A. Stover and others have worked with some ancient Latin texts3, but although a computational analysis by R. Forsyth, D. Holmes, and E. Tse confirmed the consensus that Consolatio Ciceronis is indeed a sixteenth-century forgery4, until now these methods have had only a limited impact on the Ciceronian corpus itself. We attempt to take on this task with today’s highly ad- vanced computational methods and the use of high performance com- puting (CSC supercomputer, Kajaani, Finland). After a brief account on 1 The main responsibility of the historical background and interpreting the results (chapters 1-3 and 5) lies on Raija Vainio, and that of the methods and respective parts in the results (ch. -

Thesis Submitted in Conformity with the Requirements for the Degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Graduate Department of Classics University of Toronto

An Archaeology of Cicero’s Letters: A Study of Late Republican Textual Culture by Robert McCutcheon A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Graduate Department of Classics University of Toronto © Copyright by Robert McCutcheon 2013 An Archaeology of Cicero’s Letters: A Study of Late Republican Textual Culture Robert McCutcheon Doctorate of Philosophy Department of Classics University of Toronto 2013 Abstract This dissertation examines the hermeneutic role of the material epistula in the correspondence of the Roman elite at the end of the Republic. Through close readings of descriptions of the physical letter in Cicero’s Letters and with reference to the papyrological record and later epistolary cultures, I reconstruct the meaning of the material epistula for Cicero and his social cohort. Elite epistolography was not only a site of intricate discursive strategies, but also of complex material politics. Physical aspects of the epistula – such as whose handwriting (the author’s or a scribe’s) the recipient reads, the choice of medium for the epistle, and the identity of the letter-carrier – constituted a complex social performance on the part of the epistolographer that helped to delineate both his status in the community and his relationship with the letter’s addressee. By examining how the material form of an epistula could influence the reception of its linguistic contents, this dissertation also facilitates a more nuanced understanding of Cicero’s correspondence, in particular his epistolary relations with such figures as Atticus, Caelius, Plancus, and Antony. ii The first two chapters demonstrate that the mode of production for an epistula was a key material feature that republican epistolographers used in constructing and negotiating their relationships with each other. -

Spreading and Controlling Information in the Roman

Going Viral in Ancient Rome: Spreading and Controlling Information in the Roman Republic Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Brendan James McCarthy, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2018 Dissertation Committee: Nathan S. Rosenstein, Advisor Greg Anderson Tina Sessa Copyright by Brendan McCarthy 2018 Abstract In recent years scholars have discussed the role of communication in the Roman political system. These studies have focused mostly on major public events like votes and contiones. This study will add to that discussion by looking at word-of-mouth communication. Rome’s political elite formed information networks to spread news and took great care that their public events like contiones and ludi were well attended and made news. Rome’s non-elite lived in a thriving city that encouraged the movement of people and information. Using theories taken from communications studies, sociology and the spatial turn of archeology, this study will examine the way information was spread after public events. The Roman elite relied on word-of-mouth to ensure that their reputations grew and their agendas received public support. They took great care to ensure that their public events would become news by encouraging favorable audiences to share accounts of the events with their peers. Sharing news, therefore, would have been an integral way from Romans to participate in politics. i Dedication Dedicated to my grandfather, Edwin McCarthy, who loved history and now is history ii Acknowledgements This project was a long time in the making and I am grateful for all the support I received throughout the process. -

Week 13 Cicero's Somnium Scipionis Is the Conclusion to His Dialogue

85 Week 13 During a Spanish campaign he won the admiration of the Numidian king, Cicero’s Somnium Scipionis is the conclusion to his dialogue, De re publica. Masinissa, especially by his kindly treatment of the king’s nephew. He It was an influential text throughout the Middle Ages, Renaissance, and returned to Rome and was elected to the consulship in 205, though he was Enlightenment because the dream reports the basic philosophical world view only 30 and had not held the praetorship. The senate awarded Sicily as his of the Roman empire. province, and fearing his plan to invade Africa, denied him an army. But In 129 BC, on the eve of his death, Publius Cornelius Scipio volunteers flooded from all over Italy to join him, and in 204 with proconsular Aemilianus Africanus (Scipio Aemilianus) tells of the apparition of his authority he crossed over to invade Carthage. Upon landing, he was aided adoptive grandfather, Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus (Scipio Africanus), by Masinissa. Hannibal had to be recalled from Italy (just as Scipio had 20 years before. The time of the dream (149 BC) is the eve of the third hoped), and was ultimately defeated at Zama in 202. Scipio celebrated a Punic War. Scipio Africanus was the hero of the second Punic War (over 50 magnificent triumph, was granted the cognomen “Africanus”, and was years before) and the conqueror of Hannibal. From the vantage point of the offered a dictatorship for life, which he declined. His overwhelming Milky Way where he resides in the afterlife, Scipio Africanus shows his popularity caused him difficulties later, however, when his many enemies grandson the universe as it really is. -

Cicerótól Macrobiusig – Párhuzamok Az Erények Hálózatában

ACTA CLASSICA LI. 2015. UNIV. SCIENT. DEBRECEN. pp. 31–41. THE QUESTIONS OF LIFE AND DEATH BY CICERO AND MACROBIUS* BY ORSOLYA TÓTH Abstract: To Cicero’s Somnium Scipionis Macrobius prepared a Neoplatonic commentary in Late Antiquity. On the grounds of these two works and Cicero’s other political or philosophical writings and letters this study seeks an answer to the question what similarities and differences can be demonstrated between the two authors’ way of thinking as regards the nature of the virtues, the issue of vita activa and vita contemplativa, the meaning of life and the necessity of voluntary death. Keywords: Macrobius, Cicero, virtues, voluntary death The commentary literature flourishing in the Late Antiquity is usually divided into two categories: the first is the so-called grammatical type that follows and interprets the original text almost line by line, mainly on the grounds of lan- guage, religious and literary history, like the commentaries of Donatus and Servius, and the second is the philosophical type that chooses and explains an optional section from any author’s any work more freely.1 Macrobius’ com- mentary on the Somnium Scipionis also belongs to the latter category2 that ex- amines seven sections from Cicero’s work in two books each. Number seven, the numerus plenus3 is especially favourable for the author and it seems to be justified by the fact that he deals with it through 83 paragraphs in his work:4 no other topics discussed by him get such great attention.5 Macrobius starts the first book of Commentarii in Somnium Scipionis with a prologue thus the first *This study was prepared with the support of Hungarian National Foundation for Scientific Rese- arch (OTKA), grant no.