Distribution and Conservation Status of Two Newly Described Cheirogaleid Species, Mirza Zaza and Microcebus Lehilahytsara

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Are Mouse Lemurs? in the WILD in CAPTIVITY

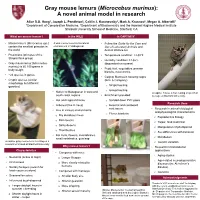

Gray mouse lemurs (Microcebus murinus): A novel animal model in research Alice S.O. Hong¹, Jozeph L. Pendleton², Caitlin J. Karanewsky², Mark A. Krasnow², Megan A. Albertelli¹ ¹Department of Comparative Medicine, ²Department of Biochemistry and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA What are mouse lemurs? In the WILD In CAPTIVITY • Mouse lemurs (Microcebus spp.) A wild mouse lemur in its natural • Follow the Guide for the Care and contain the smallest primates in environment in Madagascar. Use of Laboratory Animals and the world Animal Welfare Act • Prosimians (primates of the • Temperature condition: 74-80ºF Strepsirrhine group) • Humidity condition: 44-65% • Gray mouse lemur (Microcebus (dependent on season) murinus) is 80-100 grams in body weight. • Food: fruit, vegetables, primate biscuits, meal worms • ~24 species in genus • Caging: Marmoset housing cages • Cryptic species (similar (Britz & Company) morphology but different o genetics) Single housing o Group housing • Native to Madagascar in west and A captive mouse lemur resting on perch in south coast regions • Enrichment provided: its cage at Stanford University. • Hot and tropical climate o Sanded down PVC pipes Research Uses • Arboreal (live in trees) o External and cardboard nest boxes • Research in animal’s biological • Live in various environments: and physiological characteristics o Fleece blankets o Dry deciduous trees o Reproductive biology o Rain forests o Torpor, food restriction o Spiny deserts o Manipulation of photoperiod o Thornbushes o Sex differences with behavior • Eat fruits, flowers, invertebrates, o Metabolism small vertebrates, gum/sap A captive gray mouse lemur resting on a o Genetic variation researcher’s hand at Stanford University. -

Geogenetic Patterns in Mouse Lemurs (Genus Microcebus)

PAPER Geogenetic patterns in mouse lemurs (genus COLLOQUIUM Microcebus) reveal the ghosts of Madagascar’s forests past Anne D. Yodera,b,1, C. Ryan Campbella, Marina B. Blancob, Mario dos Reisc, Jörg U. Ganzhornd, Steven M. Goodmane,f, Kelsie E. Hunnicutta, Peter A. Larsena, Peter M. Kappelerg, Rodin M. Rasoloarisong,h, José M. Ralisonh, David L. Swofforda, and David W. Weisrocki aDepartment of Biology, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708; bDuke Lemur Center, Duke University, Durham, NC 27705; cSchool of Biological and Chemical Sciences, Queen Mary University of London, London E1 4NS, United Kingdom; dTierökologie und Naturschutz, Universität Hamburg, 20146 Hamburg, Germany; eField Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL 60605; fAssociation Vahatra, BP 3972, Antananarivo 101, Madagascar; gBehavioral Ecology and Sociobiology Unit, German Primate Centre, 37077 Goettingen, Germany; hDépartement de Biologie Animale, Université d’Antananarivo, BP 906, Antananarivo 101, Madagascar; and iDepartment of Biology, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 40506 Edited by Francisco J. Ayala, University of California, Irvine, CA, and approved May 4, 2016 (received for review February 18, 2016) Phylogeographic analysis can be described as the study of the geolog- higher elevations (generally above 1,900 m), the montane forest ical and climatological processes that have produced contemporary habitat gives way to an Ericaceae thicket. Along the western half of geographic distributions of populations and species. Here, we attempt the island, below 800 m elevation and to the west of the Central to understand how the dynamic process of landscape change on Highlands, the montane forests shift to dry deciduous forest dom- Madagascar has shaped the distribution of a targeted clade of mouse inated by drought-adapted trees and shrubs. -

Taxonomic Revision of Mouse Lemurs (Microcebus) in the Western Portions of Madagascar

International Journal of Primatology, Vol. 21, No. 6, 2000 Taxonomic Revision of Mouse Lemurs (Microcebus) in the Western Portions of Madagascar Rodin M. Rasoloarison,1 Steven M. Goodman,2 and Jo¨ rg U. Ganzhorn3 Received October 28, 1999; revised February 8, 2000; accepted April 17, 2000 The genus Microcebus (mouse lemurs) are the smallest extant primates. Until recently, they were considered to comprise two different species: Microcebus murinus, confined largely to dry forests on the western portion of Madagas- car, and M. rufus, occurring in humid forest formations of eastern Madagas- car. Specimens and recent field observations document rufous individuals in the west. However, the current taxonomy is entangled due to a lack of comparative material to quantify intrapopulation and intraspecific morpho- logical variation. On the basis of recently collected specimens of Microcebus from 12 localities in portions of western Madagascar, from Ankarana in the north to Beza Mahafaly in the south, we present a revision using external, cranial, and dental characters. We recognize seven species of Microcebus from western Madagascar. We name and describe 3 spp., resurrect a pre- viously synonymized species, and amend diagnoses for Microcebus murinus (J. F. Miller, 1777), M. myoxinus Peters, 1852, and M. ravelobensis Zimmer- mann et al., 1998. KEY WORDS: mouse lemurs; Microcebus; taxonomy; revision; new species. 1De´partement de Pale´ontologie et d’Anthropologie Biologique, B.P. 906, Universite´ d’Antana- narivo (101), Madagascar and Deutsches Primantenzentrum, Kellnerweg 4, D-37077 Go¨ t- tingen, Germany. 2To whom correspondence should be addressed at Field Museum of Natural History, Roosevelt Road at Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, Illinois 60605, USA and WWF, B.P. -

Lemurs of Madagascar – a Strategy for Their

Cover photo: Diademed sifaka (Propithecus diadema), Critically Endangered. (Photo: Russell A. Mittermeier) Back cover photo: Indri (Indri indri), Critically Endangered. (Photo: Russell A. Mittermeier) Lemurs of Madagascar A Strategy for Their Conservation 2013–2016 Edited by Christoph Schwitzer, Russell A. Mittermeier, Nicola Davies, Steig Johnson, Jonah Ratsimbazafy, Josia Razafindramanana, Edward E. Louis Jr., and Serge Rajaobelina Illustrations and layout by Stephen D. Nash IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group Bristol Conservation and Science Foundation Conservation International This publication was supported by the Conservation International/Margot Marsh Biodiversity Foundation Primate Action Fund, the Bristol, Clifton and West of England Zoological Society, Houston Zoo, the Institute for the Conservation of Tropical Environments, and Primate Conservation, Inc. Published by: IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group, Bristol Conservation and Science Foundation, and Conservation International Copyright: © 2013 IUCN Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Inquiries to the publisher should be directed to the following address: Russell A. Mittermeier, Chair, IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group, Conservation International, 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500, Arlington, VA 22202, USA Citation: Schwitzer C, Mittermeier RA, Davies N, Johnson S, Ratsimbazafy J, Razafindramanana J, Louis Jr. EE, Rajaobelina S (eds). 2013. Lemurs of Madagascar: A Strategy for Their Conservation 2013–2016. Bristol, UK: IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group, Bristol Conservation and Science Foundation, and Conservation International. 185 pp. ISBN: 978-1-934151-62-4 Illustrations: © Stephen D. -

Chitinase Expression in the Stomach of the Aye-Aye (Daubentonia

CHITINASE EXPRESSION IN THE STOMACH OF THE AYE-AYE (DAUBENTONIA MADAGASCARIENSIS). A thesis submitted To Kent State University in partial Fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Melia G. Romine August 2020 © Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Thesis written by Melia G. Romine B.S., Kent State University, 2018 M.A., Kent State University, 2020 Approved by _______________________, Advisor Dr. Anthony J. Tosi _______________________, Chair, Department of Anthropology Dr. Mary Ann Raghanti _______________________, Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Dr. Mandy Munro-Stasiuk TABLE OF CONTENTS -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------iii LIST OF FIGURES ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------v LIST OF TABLES -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------vi DEDICATION ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ------------------------------------------------------------------------------viii CHAPTERS I. INTRODUCTION ------------------------------------------------------------------------------1 FEEDING STRATEGIES ---------------------------------------------------------------------2 OPTIMAL FOOD SOURCES ----------------------------------------------------------------3 BODY SIZE -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------6 DAUBENTONIA -

Reproductive Biology of Mouse and Dwarf Lemurs of Eastern

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Open Access Dissertations 5-2010 Reproductive Biology of Mouse and Dwarf Lemurs of Eastern Madagascar, With an Emphasis on Brown Mouse Lemurs (Microcebus rufus) at Ranomafana National Park, A Southeastern Rainforest Marina Beatriz Blanco University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Blanco, Marina Beatriz, "Reproductive Biology of Mouse and Dwarf Lemurs of Eastern Madagascar, With an Emphasis on Brown Mouse Lemurs (Microcebus rufus) at Ranomafana National Park, A Southeastern Rainforest" (2010). Open Access Dissertations. 246. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations/246 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY OF MOUSE AND DWARF LEMURS OF EASTERN MADAGASCAR, WITH AN EMPHASIS ON BROWN MOUSE LEMURS (MICROCEBUS RUFUS ) AT RANOMAFANA NATIONAL PARK, A SOUTHEASTERN RAINFOREST A Dissertation Presented by MARINA BEATRIZ BLANCO Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2010 Anthropology © Copyright by Marina Beatriz Blanco 2010 All Rights Reserved REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY OF MOUSE AND DWARF LEMURS OF EASTERN MADAGASCAR, WITH AN EMPHASIS ON BROWN MOUSE LEMURS (MICROCEBUS RUFUS ) AT RANOMAFANA NATIONAL PARK, A SOUTHEASTERN RAINFOREST A Dissertation Presented by MARINA BEATRIZ BLANCO Approved as to style and content by: _______________________________________ Laurie R. -

Microcebus Griseorufus) Conservation: Local Resource Utilization and Habitat Disturbance at Beza Mahafaly, Sw Madagascar

THE HUMAN FACTOR IN MOUSE LEMUR (MICROCEBUS GRISEORUFUS) CONSERVATION: LOCAL RESOURCE UTILIZATION AND HABITAT DISTURBANCE AT BEZA MAHAFALY, SW MADAGASCAR A Dissertation Presented by EMILIENNE RASOAZANABARY Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2011 Anthropology © Copyright by Emilienne Rasoazanabary 2011 All Rights Reserved THE HUMAN FACTOR IN MOUSE LEMUR (MICROCEBUS GRISEORUFUS) CONSERVATION: LOCAL RESOURCE UTILIZATION AND HABITAT DISTURBANCE AT BEZA MAHAFALY, SW MADAGASCAR A Dissertation Presented By EMILIENNE RASOAZANABARY Approved as to style and content by: _______________________________________ Laurie R. Godfrey, Chair _______________________________________ Lynnette L. Sievert, Member _______________________________________ Todd K. Fuller, Member ____________________________________ Elizabeth Chilton, Department Head Anthropology This dissertation is dedicated to the late Berthe Rakotosamimanana and Gisèle Ravololonarivo (Both Professors in the DPAB) Claire (Cook at Beza Mahafaly) Pex and Gyca (Both nephews) Guy and Edmond (Both brothers-in-law) Claudia and Alfred (My older sister and my older brother) All of my grandparents Rainilaifiringa (Grandpa) All of the fellow gray mouse lemurs ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation has been more a process than a document; its completion is long anticipated and ever-so-welcome. So many people participated in and brought to me the most precious and profoundly appreciated support – academic, physical, and emotional. I would not have been able to conduct this work without leaning on those people. I am very grateful to every single one of them. In case you read the dissertation and find your name unlisted, just remember that my gratitude extends to each one of you. I am extremely grateful to Dr. -

January 2013

NEW PROGRAMS Duke’s research | conservation | education Alternate Winter 2013 COME LEARN WITH US! Mascot: Inside the The Duke Lemur Center is excited to introduce Mind of the two new programs to our Education Depart- Lemur ment. This winter and spring join us for our By Joel Bray, Duke student “Prosimians for Preschoolers” early childhood programs featuring two exciting parent- guided How do lemurs see the world? It’s a question I ask as classes, Lemur Play! and Junior Observers. an undergraduate researcher in a cognitive psychology These classes are designed for those little lemur lab at Duke, but I have also had the opportunity to do enthusiasts between the ages of three and five. so from a second, more unusual perspective. To find out more about the classes please visit our website (http://lemur.duke.edu/tours/ My first year at Duke, I tented with the Cameron prosimians-for-preschoolers/ ). If you would Crazies and, when given the opportunity, enthusiasti- like to ensure a space for your child, please call cally donned a Coquerel’s sifaka suit at the Duke vs. 919-401-7240. UNC basketball game. It was a hit and spawned a series of appearances on campus over the following We will also kick off our new summer camp years. The journey of that lemur culminated last spring, program this summer, July 15-19 and August when I was part of Tent #1 in Krzyzewskiville. With 5-9! This camp will be geared for upcoming 5th my group’s blessing, the lemur stood front and center to 8th graders. -

Lemurs of Madagascar and the Comoros the Lucn Red Data Book

Lemurs of Madagascar and the Comoros The lUCN Red Data Book Prepared by The World Conservation Monitoring Centre lUCN - The World Conservation Union 6(^2_ LEMURS OF MADAGASCAR and the Comoros The lUCN Red Data Book lUCN - THE WORLD CONSERVATION UNION Founded in 1948, lUCN - The World Conservation Union - is a membership organisation comprising governments, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), research institutions, and conservation agencies in 120 countries. The Union's objective is to promote and encourage the protection and sustainable utilisation of living resources. Several thousand scientists and experts from all continents form part of a network supporting the work of its six Commissions: threatened species, protected areas, ecology, sustainable development, environmental law and environmental education and training. Its thematic programmes include tropical forests, wetlands, marine ecosystems, plants, the Sahel, Antarctica, population and natural resources, and women in conservation. These activities enable lUCN and its members to develop sound policies and programmes for the conservation of biological diversity and sustainable development of natural resources. WCMC - THE WORLD CONSERVATION MONITORING CENTRE The World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) is a joint venture between the three partners in the World Conservation Strategy, the World Conservation Union (lUCN), the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Its mission is to support conservation and sustainable development by collecting and analysing global conservation data so that decisions affecting biological resources are based on the best available information. WCMC has developed a global overview database of the world's biological diversity that includes threatened plant and animal species, habitats of conservation concern, critical sites, protected areas of the world, and the utilisation and trade in wildlife species and products. -

On the Modulation and Maintenance of Hibernation in Captive Dwarf Lemurs Marina B

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN On the modulation and maintenance of hibernation in captive dwarf lemurs Marina B. Blanco 1,2*, Lydia K. Greene 1,2, Robert Schopler1, Cathy V. Williams1, Danielle Lynch1, Jenna Browning1, Kay Welser1, Melanie Simmons1, Peter H. Klopfer2 & Erin E. Ehmke1 In nature, photoperiod signals environmental seasonality and is a strong selective “zeitgeber” that synchronizes biological rhythms. For animals facing seasonal environmental challenges and energetic bottlenecks, daily torpor and hibernation are two metabolic strategies that can save energy. In the wild, the dwarf lemurs of Madagascar are obligate hibernators, hibernating between 3 and 7 months a year. In captivity, however, dwarf lemurs generally express torpor for periods far shorter than the hibernation season in Madagascar. We investigated whether fat-tailed dwarf lemurs (Cheirogaleus medius) housed at the Duke Lemur Center (DLC) could hibernate, by subjecting 8 individuals to husbandry conditions more in accord with those in Madagascar, including alternating photoperiods, low ambient temperatures, and food restriction. All dwarf lemurs displayed daily and multiday torpor bouts, including bouts lasting ~ 11 days. Ambient temperature was the greatest predictor of torpor bout duration, and food ingestion and night length also played a role. Unlike their wild counterparts, who rarely leave their hibernacula and do not feed during hibernation, DLC dwarf lemurs sporadically moved and ate. While demonstrating that captive dwarf lemurs are physiologically capable of hibernation, we argue that facilitating their hibernation serves both husbandry and research goals: frst, it enables lemurs to express the biphasic phenotypes (fattening and fat depletion) that are characteristic of their wild conspecifcs; second, by “renaturalizing” dwarf lemurs in captivity, they will emerge a better model for understanding both metabolic extremes in primates generally and metabolic disorders in humans specifcally. -

Social Organisation of the Northern Giant Mouse Lemur Mirza Zaza In

Contributions to Zoology, 82 (2) 71-83 (2013) Social organisation of the northern giant mouse lemur Mirza zaza in Sahamalaza, north western Madagascar, inferred from nest group composition and genetic relatedness E. Johanna Rode1, 2, K. Anne-Isola Nekaris2, Matthias Markolf3, Susanne Schliehe-Diecks3, Melanie Seiler1, 4, Ute Radespiel5, Christoph Schwitzer1, 6 1 Bristol Conservation and Science Foundation, c/o Bristol Zoo Gardens, Clifton, Bristol BS8 3HA, UK 2 Nocturnal Primate Research Group, School of Social Sciences and Law, Oxford Brookes University, Headington Campus, Gipsy Lane, OX3 0BP, UK 3 German Primate Center, Kellner Weg 4, 37077 Göttingen, Germany 4 School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol, Woodland Road, Bristol BS8 1UG, UK 5 Institute of Zoology, University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, Buenteweg 2, 30559 Hannover, Germany 6 E-mail: [email protected] Key words: conservation, fragmentation, genetic diversity, nest utilisation, sleeping site, small population genetics Abstract Nests and nest sites .................................................................. 75 Nest utilisation .......................................................................... 75 Shelters such as leaf nests, tree holes or vegetation tangles play a Discussion ........................................................................................ 79 crucial role in the life of many nocturnal mammals. While infor- Nests and nest sites .................................................................. 79 mation about characteristics -

Does the Grey Mouse Lemur Use Agonistic Vocalisations to Recognise Kin?

Contributions to Zoology, 87 (4) 261-274 (2018) Does the grey mouse lemur use agonistic vocalisations to recognise kin? Sharon E. Kessler1,2,3,5, Ute Radespiel3, Alida I. F. Hasiniaina3,4, Leanne T. Nash1, Elke Zimmermann3 1 Durham University, Department of Anthropology, South Rd, Durham DH1 3LE, UK. 2 Arizona State University, School of Human Evolution and Social Change, Box 872402, Tempe, AZ 85287-2402 U.S.A. 3 University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, Institute of Zoology, Bünteweg 17, 30559 Hannover, Germany. 4 Faculté des Sciences, Université de Mahajanga, BP 652, Mahajanga, Madagascar 5 E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: Playback experiment, kin recognition, solitary forager, ancestral primate, Microcebus murinus, Madagascar Abstract Playback experiments ......................................................267 Statistics ...........................................................................268 Frequent kin-biased coalitionary behaviour is a hallmark Results ...................................................................................269 of mammalian social complexity. Furthermore, selection to Genetic relatedness ..........................................................269 understand complex social dynamics is believed to underlie Differences in reactions to calls from kin, cage-mates, the co-evolution of social complexity and large brains. neighbours, and strangers ...............................................269 Vocalisations have been shown to be an important mechanism Discussion .............................................................................269