Written Evidence Submitted by the BPI (British Phonographic Industry) (PEG0226)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chris Billam-Smith

MEET THE TEAM George McMillan Editor-in-Chief [email protected] Remembrance day this year marks 100 years since the end of World War One, it is a time when we remember those who have given their lives fighting in the armed forces. Our features section in this edition has a great piece on everything you need to know about the day and how to pay your respects. Elsewhere in the magazine you can find interviews with The Undateables star Daniel Wakeford, noughties legend Basshunter and local boxer Chris Billam Smith who is now prepping for his Commonwealth title fight. Have a spooky Halloween and we’ll see you at Christmas for the next edition of Nerve Magazine! Ryan Evans Aakash Bhatia Zlatna Nedev Design & Deputy Editor Features Editor Fashion & Lifestyle Editor [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Silva Chege Claire Boad Jonathan Nagioff Debates Editor Entertainment Editor Sports Editor [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 3 ISSUE 2 | OCTOBER 2018 | HALLOWEEN EDITION FEATURES 6 @nervemagazinebu Remembrance Day: 100 years 7 A whitewashed Hollywood 10 CONTENTS /Nerve Now My personal experience as an art model 13 CONTRIBUTORS FEATURES FASHION & LIFESTYLE 18 Danielle Werner Top tips for stress-free skin 19 Aakash Bhatia Paris Fashion Week 20 World’s most boring Halloween costumes 22 FASHION & LIFESTYLE Best fake tanning products 24 Clare Stephenson Gracie Leader DEBATES 26 Stephanie Lambert Zlatna Nedev Black culture in UK music 27 DESIGN Do we need a second Brexit vote? 30 DEBATES Ryan Evans Latin America refugee crisis 34 Ella Smith George McMillan Hannah Craven Jake Carter TWEETS FROM THE STREETS 36 Silva Chege James Harris ENTERTAINMENT 40 ENTERTAINMENT 7 Emma Reynolds The Daniel Wakeford Experience 41 George McMillan REMEMBERING 100 YEARS Basshunter: No. -

View Or Download Full Colour Catalogue May 2021

VIEW OR DOWNLOAD FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE 1986 — 2021 CELEBRATING 35 YEARS Ian Green - Elaine Sunter Managing Director Accounts, Royalties & Promotion & Promotion. ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Orders & General Enquiries To:- Tel (0)1875 814155 email - [email protected] • Website – www.greentrax.com GREENTRAX RECORDINGS LIMITED Cockenzie Business Centre Edinburgh Road, Cockenzie, East Lothian Scotland EH32 0XL tel : 01875 814155 / fax : 01875 813545 THIS IS OUR DOWNLOAD AND VIEW FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE FOR DETAILS OF AVAILABILITY AND ON WHICH FORMATS (CD AND OR DOWNLOAD/STREAMING) SEE OUR DOWNLOAD TEXT (NUMERICAL LIST) CATALOGUE (BELOW). AWARDS AND HONOURS BESTOWED ON GREENTRAX RECORDINGS AND Dr IAN GREEN Honorary Degree of Doctorate of Music from the Royal Conservatoire, Glasgow (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – The Hamish Henderson Award for Services to Traditional Music (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – Hall of Fame (Ian Green) East Lothian Business Annual Achievement Award For Good Business Practises (Greentrax Recordings) Midlothian and East Lothian Chamber of Commerce – Local Business Hero Award (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Hands Up For Trad – Landmark Award (Greentrax Recordings) Featured on Scottish Television’s ‘Artery’ Series (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Honorary Member of The Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland and Haddington Pipe Band (Ian Green) ‘Fuzz to Folk – Trax of My Life’ – Biography of Ian Green Published by Luath Press. Music Type Groups : Traditional & Contemporary, Instrumental -

Laura Marling - Song for Our Daughter Episode 184

Song Exploder Laura Marling - Song For Our Daughter Episode 184 Hrishikesh: You’re listening to Song Exploder, where musicians take apart their songs and piece by piece tell the story of how they were made. My name is Hrishikesh Hirway. (“Song for Our Daughter” by LAURA MARLING) Hrishikesh: Before we start, I want to mention that, in this episode, there’s some discussions of themes that might be difficult for some: sexual harassment and assault, as well as a mention of rape and suicide. Please use your best discretion. Laura Marling is a singer and songwriter from London. She won the Brit Award for Best British Female Solo Artist - she’s been nominated five times for that, along with the Mercury Prize, and the Grammy for Best Folk Album. Since 2008, she’s released seven albums. The most recent is called Song for Our Daughter. It’s also the name of the song that she takes apart in this episode. I spoke to Laura while she was in her home studio in London. (“Song for Our Daughter” by LAURA MARLING) Laura: My name is Laura Marling. (Music fades out) Laura: This is the longest I've ever taken to write a record. You know, I started very young. I put out my first album when I was 17, and I'm now 30. When I was young, in a really wonderful way, and I think everybody experiences this when they're young, you're kind of a functioning narcissist [laughter], in that you have this experience of the world, in which you are the central character. -

19.05.21 Notable Industry Recognition Awards List • ADC Advertising

19.05.21 Notable Industry Recognition Awards List • ADC Advertising Awards • AFI Awards • AICE & AICP (US) • Akil Koci Prize • American Academy of Arts and Letters Gold Medal in Music • American Cinema Editors • Angers Premier Plans • Annie Awards • APAs Awards • Argentine Academy of Cinematography Arts and Sciences Awards • ARIA Music Awards (Australian Recording Industry Association) Ariel • Art Directors Guild Awards • Arthur C. Clarke Award • Artios Awards • ASCAP awards (American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers) • Asia Pacific Screen Awards • ASTRA Awards • Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts (AACTS) • Australian Production Design Guild • Awit Awards (Philippine Association of the Record Industry) • BAA British Arrow Awards (British Advertising Awards) • Berlin International Film Festival • BET Awards (Black Entertainment Television, United States) • BFI London Film Festival • Bodil Awards • Brit Awards • British Composer Awards – For excellence in classical and jazz music • Brooklyn International Film Festival • Busan International Film Festival • Cairo International Film Festival • Canadian Screen Awards • Cannes International Film Festival / Festival de Cannes • Cannes Lions Awards • Chicago International Film Festival • Ciclope Awards • Cinedays – Skopje International Film Festival (European First and Second Films) • Cinema Audio Society Awards Cinema Jove International Film Festival • CinemaCon’s International • Classic Rock Roll of Honour Awards – An annual awards program bestowed by Classic Rock Clio -

Pan Macmillan AUTUMN CATALOGUE 2021 PUBLICITY CONTACTS

Pan Macmillan AUTUMN CATALOGUE 2021 PUBLICITY CONTACTS General enquiries [email protected] Alice Dewing FREELANCE [email protected] Anna Pallai Amy Canavan [email protected] [email protected] Caitlin Allen Camilla Elworthy [email protected] [email protected] Elinor Fewster Emma Bravo [email protected] [email protected] Emma Draude Gabriela Quattromini [email protected] [email protected] Emma Harrow Grace Harrison [email protected] [email protected] Jacqui Graham Hannah Corbett [email protected] [email protected] Jamie-Lee Nardone Hope Ndaba [email protected] [email protected] Laura Sherlock Jess Duffy [email protected] [email protected] Ruth Cairns Kate Green [email protected] [email protected] Philippa McEwan [email protected] Rosie Wilson [email protected] Siobhan Slattery [email protected] CONTENTS MACMILLAN PAN MANTLE TOR PICADOR MACMILLAN COLLECTOR’S LIBRARY BLUEBIRD ONE BOAT MACMILLAN Nine Lives Danielle Steel Nine Lives is a powerful love story by the world’s favourite storyteller, Danielle Steel. Nine Lives is a thought-provoking story of lost love and new beginnings, by the number one bestseller Danielle Steel. After a carefree childhood, Maggie Kelly came of age in the shadow of grief. Her father, a pilot, died when she was nine. Maggie saw her mother struggle to put their lives back together. As the family moved from one city to the next, her mother warned her about daredevil men and to avoid risk at all cost. Following her mother’s advice, and forgoing the magic of first love with a high-school boyfriend who she thought too wild, Maggie married a good, dependable man. -

FINAL- Jupiter Rising Press Release

PRESS RELEASE: 5 February 2019 FESTIVAL LAUNCH: JUPITER RISING 2019 The Comet is Coming. Image by Fabrice Bourgelle, 2019 • The Comet is Coming, The Vaselines, Alpha Maid and OH141 announced among the first artists to perform at JUPITER RISING, Scotland’s newest art and music festival • A new visual identity by Jim Lambie launches online today as part of JUPITER RISING’S artist-commission programme, which also includes the premiere of new work by Mary Hurrell as part of Edinburgh Art Festival • Curated as part of Jupiter Artland’s artistic-programme, the festival will weave throughout the 100-acre sculpture park offering a unique experience that transcends the music and art worlds JUPITER RISING: 23 – 25 August 2019 Download the trailer here. Scotland’s newest festival of cutting-edge art and music, JUPITER RISING has today announced the first artist line-up, with Mercury-prize nominees The Comet is Coming, The Vaselines, Alpha Maid and OH141. JUPITER RISING takes place within an iconic landscape of installations by world-leading artists at Jupiter Artland. A new visual identity by Turner-Prize nominated Glasgow-based contemporary visual artist, Jim Lambie launches online today, the first of JUPITER RISING’S artist-commission programme, made in collaboration with designer Simon Sweeney. The festival will also premiere a new work by artist Mary Hurrell as part of Edinburgh Art Festival. Founding Director of Jupiter Artland Nicky Wilson says: “Art, music, performance, feasting and dancing; I can’t think of a better way of evoking the spirit of Jupiter whilst supporting emerging artists and performers. This art-led festival will create a space for experimental, content-rich projects in an iconic landscape.” Revellers can expect an intelligently curated programme, from indie rock to experimental dance and psychedelic jazz. -

All Around the World the Global Opportunity for British Music

1 all around around the world all ALL British Music for Global Opportunity The AROUND THE WORLD CONTENTS Foreword by Geoff Taylor 4 Future Trade Agreements: What the British Music Industry Needs The global opportunity for British music 6 Tariffs and Free Movement of Services and Goods 32 Ease of Movement for Musicians and Crews 33 Protection of Intellectual Property 34 How the BPI Supports Exports Enforcement of Copyright Infringement 34 Why Copyright Matters 35 Music Export Growth Scheme 12 BPI Trade Missions 17 British Music Exports: A Worldwide Summary The global music landscape Europe 40 British Music & Global Growth 20 North America 46 Increasing Global Competition 22 Asia 48 British Music Exports 23 South/Central America 52 Record Companies Fuel this Global Success 24 Australasia 54 The Story of Breaking an Artist Globally 28 the future outlook for british music 56 4 5 all around around the world all around the world all The Global Opportunity for British Music for Global Opportunity The BRITISH MUSIC IS GLOBAL, British Music for Global Opportunity The AND SO IS ITS FUTURE FOREWORD BY GEOFF TAYLOR From the British ‘invasion’ of the US in the Sixties to the The global strength of North American music is more recent phenomenal international success of Adele, enhanced by its large population size. With younger Lewis Capaldi and Ed Sheeran, the UK has an almost music fans using streaming platforms as their unrivalled heritage in producing truly global recording THE GLOBAL TOP-SELLING ARTIST principal means of music discovery, the importance stars. We are the world’s leading exporter of music after of algorithmically-programmed playlists on streaming the US – and one of the few net exporters of music in ALBUM HAS COME FROM A BRITISH platforms is growing. -

N Ew Y O R K F Lu T E F a Ir 2021

The New York Flute Club Nancy Toff, President Deirdre McArdle, Flute Fair Program Chair The New York Flute Fair 2021 A VIRTUAL TOOLBOX with guest artist Julien Beaudiment Principal flutist, Lyon (France) Opera Orchestra Saturday and Sunday, April 10 and 11, 2021 via Zoom NEW YORK FLUTE FAIR 2021 BOARD OF DIRECTORS NANCY TOFF, President PATRICIA ZUBER, First Vice President KAORU HINATA, Second Vice President DEIRDRE MCARDLE, Recording Secretary KATHERINE SAENGER, Membership Secretary MAY YU WU, Treasurer AMY APPLETON JEFF MITCHELL JENNY CLINE NICOLE SCHROEDER RAIMATO DIANE COUZENS LINDA RAPPAPORT FRED MARCUSA JAYN ROSENFELD JUDITH MENDENHALL RIE SCHMIDT MALCOLM SPECTOR ADVISORY BOARD JEANNE BAXTRESSER ROBERT LANGEVIN STEFÁN RAGNAR HÖSKULDSSON MICHAEL PARLOFF SUE ANN KAHN RENÉE SIEBERT PAST PRESIDENTS Georges Barrère, 1920-1944 Eleanor Lawrence, 1979-1982 John Wummer, 1944-1947 John Solum, 1983-1986 Milton Wittgenstein, 1947-1952 Eleanor Lawrence, 1986-1989 Mildred Hunt Wummer, 1952-1955 Sue Ann Kahn, 1989-1992 Frederick Wilkins, 1955-1957 Nancy Toff, 1992-1995 Harry H. Moskovitz, 1957-1960 Rie Schmidt, 1995-1998 Paige Brook, 1960-1963 Patricia Spencer, 1998-2001 Mildred Hunt Wummer, 1963-1964 Jan Vinci, 2001-2002 Maurice S. Rosen, 1964-1967 Jayn Rosenfeld, 2002-2005 Harry H. Moskovitz, 1967-1970 David Wechsler, 2005-2008 Paige Brook, 1970-1973 Nancy Toff, 2008-2011 Eleanor Lawrence, 1973-1976 John McMurtery, 2011-2012 Harold Jones, 1976-1979 Wendy Stern, 2012-2015 Patricia Zuber, 2015-2018 FLUTE FAIR STAFF Program Chair: Deirdre McArdle -

A Centenary Celebration 100 Years of the London Chamber Orchestra

Available to stream online from 7:30pm, 7 May 2021 until midnight, 16 May 2021 A Centenary Celebration 100 years of the London Chamber Orchestra Programme With Christopher Warren-Green, conductor Handel Arrival of the Queen of Sheba Jess Gillam, presenter Mozart Divertimento in D Major, K205, I. Largo – Allegro Debussy Danses Sacrée et Profane Maconchy Concertino for Clarinet and Orchestra, III. Allegro Soloists Mozart Eine Kleine Nachtmusik, I. Allegro Anne Denholm, harp Britten Courtly Dance No. 5 Mark van de Wiel, clarinet Maxwell Davies Farewell to Stromness Various A Century of Music (premiere) Soloists, A Century of Music Elgar Introduction and Allegro Mary Bevan, soprano Pekka Kuusisto, violin London Chamber Orchestra Alison Balsom, trumpet Ksenija Sidorova, accordion Violin 1 Viola Flute & Piccolo Benjamin Beilman, violin Clio Gould Rosemary Warren-Green Harry Winstanley Jess Gillam, saxophone Manon Derome Kate Musker Gina McCormack Becky Low Oboe Sophie Lockett Jenny Coombes Gordon Hunt Imogen East Alison Alty Composers, A Century of Music Eunsley Park Cello Rob Yeomans Robert Max Clarinet & Bass Clarinet John Rutter Edward Bale Joely Koos Mark van de Wiel Freya Waley-Cohen Julia Graham Violin 2 Rachael Lander Bassoon Paul Max Edlin Charles Sewart Meyrick Alexander George Morton Anna Harpham Bass Alexandra Caldon Andy Marshall Horn Tim Jackson Guy Button Ben Daniel-Greep Richard Watkins Jo Godden Michael Thompson Gabriel Prokofiev Harriet Murray Percussion Cheryl Frances-Hoad Julian Poole Trumpet Ross Brown If you’re joining us in the virtual concert hall, we’d love to know about it! Tag us on your social media using the hashtag #LCOTogether George Frideric Handel Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Arrival of the Queen of Sheba Divertimento in D Major, K205 I. -

Sport and Masculinity in Victorian Popular

MARKED MEN: SPORT AND MASCULINITY IN VICTORIAN POPULAR CULTURE, 1866-1904 by Shannon Rose Smith A thesis submitted to the Department of English Language and Literature In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (July 2012) Copyright ©Shannon Rose Smith, 2012 Abstract In Marked Men: Sport and Masculinity in Victorian Popular Culture, 1866-1904 I examine the representation of the figure of the Victorian sportsman in different areas of nineteenth-century popular culture – newspapers, spectacular melodrama, and series detective fiction – and how these depictions register diverse incarnations of this figure, demonstrating a discomfort with, and anxiety about, the way in which the sporting experience after the Industrial Revolution influenced gender ideology, specifically that related to ideas of manliness. Far from simply celebrating the modern experience of sport as one that works to produce manly men, coverage in the Victorian press of sporting events such as the 1869 Oxford-Cambridge Boat Race, spectacular melodramas by Dion Boucicault, and series detective fiction by Arthur Conan Doyle and Arthur Morrison, all recognize that the relationship between men and modern sport is a complex, if fraught one; it produces men who are “marked” in a variety of ways by their sporting experience. This recognition is at the heart of our own understandings of this relationship in the twenty-first century. ii Acknowledgements I would like to express my lasting gratitude to Maggie Berg and Mary Louise Adams, under whose supervision I conducted the research for my study; both have had a marked impact on the kind of scholar I have become and both have taught me many lessons about the challenges and joys of scholarship. -

John Marks Exits Spotify SIGN up HERE (FREE!)

April 2, 2021 The MusicRow Weekly Friday, April 2, 2021 John Marks Exits Spotify SIGN UP HERE (FREE!) If you were forwarded this newsletter and would like to receive it, sign up here. THIS WEEK’S HEADLINES John Marks Exits Spotify Scotty McCreery Signs With UMPG Nashville Brian Kelley Partners With Warner Music Nashville For Solo Music River House Artists/Sony Music Nashville Sign Georgia Webster Sony Music Publishing Renews With Tom Douglas John Marks has left his position as Global Director of Country Music at Spotify, effective March 31, 2021. Date Set For 64th Annual Grammy Awards Marks joined Spotify in 2015, as one of only two Nashville Spotify employees covering the country market. While at the company, Marks was instrumental in growing the music streaming platform’s Hot Country Styles Haury Signs With brand, championing new artists, and establishing Spotify’s footprint in Warner Chappell Music Nashville. He was an integral figure in building Spotify’s reputation as a Nashville global symbol for music consumption and discovery and a driver of country music culture; culminating 6 million followers and 5 billion Round Hill Inks Agreement streams as of 4th Quarter 2020. With Zach Crowell, Establishes Joint Venture Marks spent most of his career in programming and operations in With Tape Room terrestrial radio. He moved to Nashville in 2010 to work at SiriusXM, where he became Head of Country Music Programming. During his 5- Carrie Underwood Deepens year tenure at SiriusXM, he brought The Highway to prominence, helping Her Musical Legacy With ‘My to bring artists like Florida Georgia Line, Old Dominion, Kelsea Ballerini, Chase Rice, and Russell Dickerson to a national audience. -

Nominations List

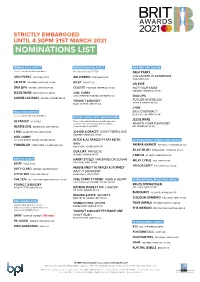

STRICTLY EMBARGOED UNTIL 4.30PM 31ST MARCH 2021 NOMINATIONS LIST FEMALE SOLO ARTIST BREAKTHROUGH ARTIST MASTERCARD ALBUM In association with Amazon Music In association with TikTok ARLO PARKS ARLO PARKS TRANSGRESSIVE ARLO PARKS TRANSGRESSIVE COLLAPSED IN SUNBEAMS TRANSGRESSIVE CELESTE POLYDOR, UNIVERSAL MUSIC BICEP NINJA TUNE CELESTE DUA LIPA WARNER, WARNER MUSIC CELESTE POLYDOR, UNIVERSAL MUSIC NOT YOUR MUSE POLYDOR, UNIVERSAL MUSIC JESSIE WARE EMI, UNIVERSAL MUSIC JOEL CORRY ASYLUM/PERFECT HAVOC, WARNER MUSIC DUA LIPA LIANNE LA HAVAS WARNER, WARNER MUSIC YOUNG T & BUGSEY FUTURE NOSTALGIA WARNER, WARNER MUSIC BLACK BUTTER, SONY MUSIC J HUS MALE SOLO ARTIST BIG CONSPIRACY BLACK BUTTER, SONY MUSIC In association with Amazon Music BRITISH SINGLE WITH MASTERCARD JESSIE WARE AJ TRACEY AJ TRACEY The top ten identified by chart eligible sales success then voted for by The Academy, WHAT'S YOUR PLEASURE? HEADIE ONE RELENTLESS, SONY MUSIC Supported by Capital FM EMI, UNIVERSAL MUSIC J HUS BLACK BUTTER, SONY MUSIC 220 KID & GRACEY DON'T NEED LOVE POLYDOR, UNIVERSAL MUSIC JOEL CORRY ASYLUM/PERFECT HAVOC, WARNER MUSIC AITCH & AJ TRACEY FT TAY KEITH INTERNATIONAL FEMALE SOLO ARTIST RAIN YUNGBLUD INTERSCOPE, UNIVERSAL MUSIC ARIANA GRANDE REPUBLIC, UNIVERSAL MUSIC NQ, VIRGIN, UNIVERSAL MUSIC BILLIE EILISH INTERSCOPE, UNIVERSAL MUSIC DUA LIPA PHYSICAL WARNER, WARNER MUSIC CARDI B ATLANTIC, WARNER MUSIC BRITISH GROUP HARRY STYLES WATERMELON SUGAR MILEY CYRUS RCA, SONY MUSIC COLUMBIA, SONY MUSIC BICEP NINJA TUNE TAYLOR SWIFT EMI, UNIVERSAL MUSIC HEADIE