An Exploration of Offender Characteristics, Criminal History Information and Specialisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1.1 Compare Criminal Behaviour and Deviance

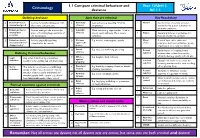

1.1 Compare criminal behaviour and Year 12/Unit 2. Criminology deviance AC 1.1 Defining deviance Acts that are criminal Key Vocabulary 1 Behaviour that is Such as heroically risking your own 1 Summary Less serious e.g. speeding. Tried by 1 Norms Specific rules or socially accepted unusual and good life to save someone else. offences magistrates. standards that govern behaviour in particular situations. 2 Behaviour that is Such as talking to the trees in the 2 Indictable More serious e.g. rape/murder. Tried in unusual and park, or hoarding huge quantities of offences crown court with jury. More severe 2 Values General principles or guidelines for eccentric old newspapers. sentences. how we should live our lives. 3 Behaviour that is Such as physically attacking 3 Violence E.g. murder, manslaughter, assault 3 Moral A set of basic rules, values and unusual and bad or someone for no reason. against the codes prinicples, held by an individual, group, disapproved of person organisation or society as a whole. 4 Sexual E.g. rape, sex trafficking, grooming. 4 Formal Punishments for breaking formal offences Defining Criminal behaviour sanction written rules or laws. Imposed by Offences official bodies e.g. courts, schools etc. Legal Any action forbidden by criminal law – 5 E.g. burglary, theft, robbery. 1 against definition 5 Informal Disapproval shown to a person for usually involves actus rea and mens rea property sanction breaking unwritten rules, such as telling 2 Social This includes consideration of differing 6 Fraud and E.g. frauds by company directors, benefit off or ignoring them. -

Criminal Law: Conspiracy to Defraud

CRIMINAL LAW: CONSPIRACY TO DEFRAUD LAW COMMISSION LAW COM No 228 The Law Commission (LAW COM. No. 228) CRIMINAL LAW: CONSPIRACY TO DEFRAUD Item 5 of the Fourth Programme of Law Reform: Criminal Law Laid before Parliament bj the Lord High Chancellor pursuant to sc :tion 3(2) of the Law Commissions Act 1965 Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 6 December 1994 LONDON: 11 HMSO E10.85 net The Law Commission was set up by section 1 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. The Commissioners are: The Honourable Mr Justice Brooke, Chairman Professor Andrew Burrows Miss Diana Faber Mr Charles Harpum Mr Stephen Silber QC The Secretary of the Law Commission is Mr Michael Sayers and its offices are at Conquest House, 37-38 John Street, Theobalds Road, London, WClN 2BQ. 11 LAW COMMISSION CRIMINAL LAW: CONSPIRACY TO DEFRAUD CONTENTS Paragraph Page PART I: INTRODUCTION 1.1 1 A. Background to the report 1. Our work on conspiracy generally 1.2 1 2. Restrictions on charging conspiracy to defraud following the Criminal Law Act 1977 1.8 3 3. The Roskill Report 1.10 4 4. The statutory reversal of Ayres 1.11 4 5. Law Commission Working Paper No 104 1.12 5 6. Developments in the law after publication of Working Paper No 104 1.13 6 7. Our subsequent work on the project 1.14 6 B. A general review of dishonesty offences 1.16 7 C. Summary of our conclusions 1.20 9 D. -

Criminal Code 2003.Pmd 273 11/27/2004, 12:35 PM 274 No

273 No. 9 ] Criminal Code [2004. SAINT LUCIA ______ No. 9 of 2004 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS CHAPTER ONE General Provisions PART I PRELIMINARY Section 1. Short title 2. Commencement 3. Application of Code 4. General construction of Code 5. Common law procedure to apply where necessary 6. Interpretation PART II JUSTIFICATIONS AND EXCUSES 7. Claim of right 8. Consent by deceit or duress void 9. Consent void by incapacity 10. Consent by mistake of fact 11. Consent by exercise of undue authority 12. Consent by person in authority not given in good faith 13. Exercise of authority 14. Explanation of authority 15. Invalid consent not prejudicial 16. Extent of justification 17. Consent to fight cannot justify harm 18. Consent to killing unjustifiable 19. Consent to harm or wound 20. Medical or surgical treatment must be proper 21. Medical or surgical or other force to minors or others in custody 22. Use of force, where person unable to consent 23. Revocation annuls consent 24. Ignorance or mistake of fact criminal code 2003.pmd 273 11/27/2004, 12:35 PM 274 No. 9 ] Criminal Code [2004. 25. Ignorance of law no excuse 26. Age of criminal responsibility 27. Presumption of mental disorder 28. Intoxication, when an excuse 29. Aider may justify same force as person aided 30. Arrest with or without process for crime 31. Arrest, etc., other than for indictable offence 32. Bona fide assistant and correctional officer 33. Bona fide execution of defective warrant or process 34. Reasonable use of force in self-defence 35. Defence of property, possession of right 36. -

Stuart Dingle YEAR of CALL: 2011

Stuart Dingle YEAR OF CALL: 2011 EXPERTISE Stuart undertakes criminal defence and prosecution work. He has defended in a wide range of cases, including section 18 GBHs, Fraud, trading standards infringements, aggravated burglaries, knifepoint robberies, violent disorder, indecent images, and violence including threats to kill. Stuart has a successful appellate practice and has had his cases referenced in Blackstones. Stuart defends in POCA proceedings and complex VAT/excise frauds. Stuart has particular experience of football disorder and defending against the imposition of Football Banning Orders. As well as representing private individuals Stuart has appeared on behalf of many fan support groups and travels across the country to represent fans in both Criminal cases and civil orders. Before his independent practice Stuart worked as a litigator and clerk, working on several multi-handed murders. Stuart has particular experience of considering pathological evidence. Stuart has successfully prosecuted and defended in a number of cases involving expert evidence and the consideration and cross examining of experts, including private driving, cell site, and medical causation evidence. Stuart is currently a Level 2 Panel Advocate for the CPS, and his casework includes specialist experience in domestic violence prosecution and advice. Stuart is also regularly instructed by the serious fraud division to deal with revenue, benefit and complex fraud cases. Stuart has experience advancing special hardship arguments to retain driving licences and has been sought to give advice on a variety of matters relating to driving law. In addition to crime and associated matters, Stuart also regular appears for quasi-criminal and regulatory matters including contested Football Banning Orders and Sexual Risk Orders. -

Colin Banham Crime

Colin Banham Crime Colin has over 17 years’ experience both defending and prosecuting in the criminal courts. He has been instructed as a leading Junior, led Junior and acting alone in serious and complex criminal allegations. He regularly defends and prosecutes cases including aggravated burglary, grievous bodily harm with intent, violent disorder, drugs conspiracies, robbery and large-scale fraud. Colin is graded by the CPS as a Level 4 Prosecutor and is a member of the Specialist Panels for Fraud (including fiscal fraud) and Serious Year of Call: 1999 Crime (including terrorism). Clerks Colin has extensive experience in serious road traffic offences. He is regularly instructed by insurers to represent defendants, particularly in Senior Practice Manager cases involving serious injury with underlying civil litigation. He accepts Andrew Trotter private instructions in all forms of motoring offences either directly or by referral. Chief Executive & Director of Clerking RECENT CASES Tony McDaid R v RS, DB & KM (2016): Instructed by the NCA in a multi-handed Contact a Clerk conspiracy to supply Class A drugs amounting to £50.4m. The case Tel: +44 (0) 845 210 5555 was conducted against a silk and two leading juniors. Fax: +44 (0) 121 606 1501 [email protected] R v KS-R (2016): Case involving allegations of causing serious injury by dangerous driving. R v CP (2016): Successfully defending a middle-aged lady alleged to have defrauded a pension scheme. R v ZN (2016): Defending a male alleged to have conspired to import a large amount of Khat into the UK. R v AB, PB & AE (2016): Prosecuting an allegation of conspiracy to supply cannabis amounting to almost £500,000. -

Offences Against Public Order

Ormerod & Laird: Smith, Hogan, and Ormerod's Criminal Law, 15th edition 31 Offences against public order 31.1 The Public Order Act 1986 31.1.1 Background The Public Order Act 1986 replaced the ancient common law offences of riot, rout, unlawful assembly and affray and some statutory offences relating to public order1 with new offences. These are, in descending order of gravity: s 1 riot; s 2 violent disorder; and, s 3 affray. In addition to these more serious offences, the Act created lower level offences: s 4 (threatening, abusive or insulting conduct intended, or likely, to provoke violence or cause fear of violence); s 5 (threatening or abusive conduct likely to cause harassment, alarm or distress); and s 4A (threatening, abusive or insulting conduct intentionally causing harassment, alarm 1 For the law before the 1986 Act, see the 5th edition of this book, Ch 20; for the background to the 1986 Act, see the Home Office, Review of the Public Order Act and Related Legislation (1980) Cmnd 7891 and Law Com Working Paper No 82 (1982) and LC 123, Offences Relating to Public Disorder (1983). For detailed studies of the new law at the time it was enacted, see R Card, Public Order: The New Law (1987) and ATH Smith, Offences against Public Order (1987). For a more recent detailed study of the offences, see P Thornton et al, The Law of Public Order and Protest (2010). © Oxford University Press, 2018. Ormerod & Laird: Smith, Hogan, and Ormerod's Criminal Law, 15th edition or distress) as added by subsequent legislation.2 These latter offences have become very heavily used. -

An Overview of the Prison Population of England and Wales Peter Cuthbertson

Who goes to prison? An overview of the prison population of England and Wales Peter Cuthbertson December 2017 Summary What sort of offence, and what sort of criminal history, persuades the courts to impose a custodial sentence? Much of the debate around sentencing, and the appropriate size of the prison population, rests on this question. It is widely suggested on one side of the debate that the courts persistently refuse to incarcerate large numbers of hardened criminals, instead imposing non-custodial sentences like confetti. Some campaigners on the other side argue that prison should be reserved for serious, repeat offenders. In so doing, they imply that a large number of prisoners are in fact first-time or minor offenders who are essentially harmless when they enter the prison gates (but often emerge schooled in crime). A criminal justice system which passes more than 1.2 million sentences a year lends itself well to many striking individual anecdotes which can be used to imply that sentencing is too soft, too harsh, or just right. But any anecdote can be a misleading, exceptional case. This briefing therefore avoids the anecdotal and explores the broad picture of those who are incarcerated. It takes a full year of sentencing data – 2016, in which 98,527 custodial sentences were imposed on 89,812 individuals in England and Wales – and investigates those individuals’ criminal history and the crimes for which they were incarcerated. The sentencing data reveal: Prolific criminals dominate the prison population 70% of custodial sentences are imposed on those with at least seven previous convictions or cautions, and 50% are imposed on those with at least 15 previous convictions or cautions. -

Statistics on Crime and the Criminal Justice System: Offence Definitions and Explanatory Notes for Countries Unable to Meet

Annex A Last update of this document: 19 March 2009 Eurostat, Statistical Office of the European Communities Unit F5 Health and Food Safety Statistics L-2920 Luxembourg Statistics on crime and the criminal justice system: Offence definitions and explanatory notes for countries unable to meet the standard definition CONTENTS Crimes recorded by the police: Total crime .............................................................2 Crimes recorded by the police: Homicide (country)................................................4 Crimes recorded by the police: Homicide (city).......................................................6 Crimes recorded by the police: Violent crime..........................................................8 Crimes recorded by the police: Robbery................................................................10 Crimes recorded by the police: Domestic burglary...............................................11 Crimes recorded by the police: Theft of a motor vehicle......................................13 Crimes recorded by the police: Drug trafficking....................................................14 Number of police officers ........................................................................................16 Prison population .....................................................................................................17 1 Crimes recorded by the police: Total crime Definition: These figures include offences against the penal code or criminal code. Less serious crimes (misdemeanours) are generally excluded. -

Lalith De Kauwe

Lalith de Kauwe YEAR OF CALL: 1978 Lalith specialises in serious criminal defence. He has acted in many cases of murder, serious violence, large-scale Class A drug dealing and importation, human trafficking, public order and complex, high-value fraud. Throughout, his legal practice has been informed by his belief in social justice, civil rights and a commitment to assisting disadvantaged communities. "Lalith is a fearless defender who makes his presence known in court. He is a formidable jury advocate who fights tenaciously for his clients." MANOJ RUPASINGHE, SENIOR PARTNER, LLOYDS PR SOLICITORS "Lalith has all the skills that you could wish to find in a senior advocate. He has the ability to consistently secure acquittals against the odds." AMIR AHMAD, SOLICITOR, IMRAN KHAN AND PARTNERS SOLICITORS "Lalith is an excellent leading counsel. He stays one step ahead of the opposition whilst maintaining excellent rapport with clients." SISIRA POLPITIYA, SENIOR PARTNER, POLPITIYA & CO SOLICITORS "A fearless advocate who fights tooth and nail for his clients, no matter how big or small the case. Makes his clients comfortable and is a man of principle." SEAN NEVILLE, SOLICITOR, SATHA & CO SOLICITORS If you would like to get in touch with Lalith please contact the clerking team: [email protected] | +44 (0)20 7993 7600 You can also contact Lalith directly: +44 (0)20 7993 7722 CRIMINAL DEFENCE Lalith specialises in serious criminal defence. He has acted in many cases of murder, serious violence, large- scale Class A drug dealing and importation, human trafficking, and public order. NOTABLE CASES R v R - Successfully defended at the Central Criminal Court. -

Marianne Alton

Marianne Alton Call to the Bar: 2014 Marianne is a diligent and persuasive advocate who prides herself on meticulous case preparation and client care. She enjoys a reputation for hard work and sound judgement. As well as undertaking work typical of her call, she has acted as junior counsel in a series of significant pieces of criminal litigation including cases rooted in organised crime. Alongside maintaining a busy practice in England, Marianne is a trustee of a legal charity CONTACT DETAILS Evolve - FILA that provides pro bono assistance in Uganda to improve access to justice, build capacity within the legal profession and promote fairness, integrity and efficiency Email: within the Ugandan criminal justice system. In November 2018, Marianne was selected [email protected] as Young Pro Bono Barrister of the Year at the Bar Council’s Annual and Young Bar Conference in recognition of her pro bono work in Uganda. Telephone: CRIME 0161 832 5701 Marianne is regularly instructed in a wide range of criminal defence and prosecution work, PRACTICE AREAS including offences of serious violence, dishonesty, drugs, sexual offences, public disorder, Business Crime & Financial Regulation regulatory offences and confiscation proceedings. Marianne prepares and presents legal applications and arguments, such as dismissal, abuse of process, disclosure, applications to Criminal Law exclude evidence and submissions of no case to answer. In addition to rapidly developing a successful defence practice, Marianne is regularly instructed to prosecute both in private Health & Safety prosecutions and on behalf of the Crown Prosecution Service. She is currently a level 3 CPS Prison Law panel prosecutor. -

International Classification of Crime for Statistical Purposes (Iccs)

Statistical Commission Background document Forty-sixth session Available in English only 3 – 6 March 2015 Item 3(c) of the provisional agenda Crime statistics INTERNATIONAL CLASSIFICATION OF CRIME FOR STATISTICAL PURPOSES (ICCS) VERSION 1.0 February 2015 Prepared by United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) Terrorism HomicideHijacking Trafficking in wildlife Burglary Assault Piracy Corruption Kidnapping 0207 Illicit enrichment 0308014 Smuggling of migrants Child pornography 0609 Sexual exploitation rty 05 Trafficking in persons Deprivation of libe Robbery Fraud Theft Forced labour Rape INTERNATIONAL CLASSIFICATION OF CRIME FOR STATISTICAL PURPOSES (ICCS) VERSION 1.0 February 2015 2013 Copyright © 2015, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Acknowledgments The development of the International Classification of Crime for Statistical Purposes was coordinated by the UNODC Research and Trend Analysis Branch (RAB), Division of Policy Analysis and Public Affairs (DPA), under the supervision of Jean-Luc Lemahieu, Director of DPA, Angela Me, Chief of RAB, and Chloé Carpentier, Chief of RAB Statistics and Surveys Section. Core team Research coordination and report preparation Enrico Bisogno Michael Jandl Lucia Motolinia Carballo Felix Reiterer Atsuki Takahashi Graphic design and layout: Suzanne Kunnen Kristina Kuttnig Editing: Jonathan Gibbons The International Classification of Crime for Statistical Purposes (ICCS) was developed using the “Principles and framework for an international classification of crimes for statistical purposes” produced by the UNECE-UNODC Joint Task Force on Crime Classification and endorsed by the Conference of European Statisticians in 2012. The ICCS was produced on the basis of the plan to finalize by 2015 an international classification of crime for statistical purposes, as approved by the Statistical Commission in its decision 44/110 and by the Economic and Social Council in its resolution 2013/37. -

Crimes Act 2011

Crimes 2011-23 CRIMES ACT 2011 Principal Act Act. No. 2011-23 Commencement (LN. 2012/185) 23.11.2012 Assent 15.8.2011 Amending Relevant current Commencement enactments provisions date Act. 2012-13 ss. 113(1) & (1)(a), (2), (3) & (4), 124(1), 176(a), 266A, 306(1)(c),(d) & (e), 307(5)(c) & (d), 308(1) & (1)(a), 555(1) & (1)(b), Schs. 2 & 3 23.11.20121 LN. 2013/049 Sch. 3 14.3.2013 2013/057 ss. 191A to 191D, 280, 281, 282, 283, 284, 285 & Sch. 4 4.4.2013 Act. 2013-21 ss. 87(3), (7), 91(1)(a), 91(2),(3), 92(1), 92A, 92B, 93(1), 93A, 94(5),(6), 95(1),(8), 95A, 97A, 98, 99(1)(a),(b), (3), 100(1)(a), (b), (2)(c), 101(1)(a), (b), (2), (2)(c), 102(1)(a), (b), (2), 103(1)(a), (b), (3), (4), (5), (6), 104(1)(a), (b), (3), 111(2), 111A, 112(2)(b)(ii), 112A- 112D, 113A-D, 114A-D, 115A-D, 116,(1), (5A), (6A), (6B), (8), 116A- D, 117(1), (2), 117A, 305(1), 10.10.20132 307(5)(d), 315A-F 2013-26 ss. 94A 28.11.2013 LN. 2013/189 ss. 228(5)(b), 229(5)(b), 230(5)(b), 231(5)(b), 251(3)(b) & 252(3)(b) 18.12.2013 Act. 2014-03 s. 547 27.2.2014 LN. 2014/217 s. 385(1A), (2) 1.12.2014 Act. 2014-33 s. 555(1)(b) 1.1.2015 LN. 2015/140 ss.