Principles and Framework for an International Classification of Crimes for Statistical Purposes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report to the Nation on Crime and Justice, Second Edition

U.S. Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics Report to the Nation on Crime and Justice Second edition NCJ-105506, March 1988 U.S. Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics Steven R. Schlesinger Director Marianne W. Zawitz Editor Contents Introduction iii I. The criminal event 1 II. The victim 23 Ill. The offender 39 IV. The response to crime 55 1. An overview 56 2. Entry into the criminal justice system 62 3. Prosecution and pretrial services 71 4. Adjudication 81 5. Sentencing and sanctions 90 6. Corrections 102 V. The cost of justice 113 Index 128 ii Report to the Nation on Crime and Justice Introduction The Bureau of Justice Statistics presents This edition contains additional material this second comprehensive picture of on such common law crimes as homi- crime and criminal justice in the United cide, robbery, and burglary; drunk driv- States. Relying heavily on graphics and ing; white-collar crime; high technology a nontechnical format, it brings together crime; organized crime; State laws that a wide range of data from BJS's own govern citizen use of deadly force; pri- statistical series, the FBI Uniform Crime vate security; police deployment; sen- Reports, the Bureau of the Census, the tencing practices; forfeiture; sentencing National Institute of Justice, the Office outcomes; time served in prison and of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency jail; facilities crowding; recidivism; the Prevention, and many other research cost of crime; and privatization of crimi- and reference sources. Because it ana- nal justice functions. lyzes these and other rich data sources, this report should interest the general Graphic excellence and clarity of public as well as criminal justice practi- expression are the hallmarks of this tioners, researchers, and educators in attempt to assist the Nation as it seeks our high schools and colleges. -

Substantive Criminal Law: Principles and Working 1 Vocabulary

55256_CH01_001_016.pdf:55256_CH01_001_016.pdf 12/18/09 1:58 PM Page 1 CHAPTER Substantive Criminal Law: Principles and Working 1 Vocabulary Key Terms Actual cause Ecclesiastical courts Positive law Actus reus Federalism Precedent Administrative law Felony Preponderance of the evidence Attendant circumstances General intent Procedural law Beyond a reasonable doubt Gross misdemeanor Property crime Burden of proof Injunctive relief Proximate cause But-for test Intervening cause Punitive damage Canon law Jurisdiction Recklessness Capital felony Kings courts Republic Case law Law courts Social contract theory Civil law Least restrictive mechanism Specific intent Code of Hammurabi Legal cause Stare decisis Common law Lesser included offense Statutory law Compensatory damage Mala in se Strict liability Constitutional law Mala prohibita Substantial factor test Constructive intent Mens rea Substantive law Corpus delicti Misdemeanor Tort Courts of equity Misprision of felony Tortfeasor Crime Natural law Transferred intent Criminal law Negligence Uniform Crime Reports Culpable Nulla poena sine lege Violation Declaratory relief Ordinance Violent crime Democracy Ordinary misdemeanor Wobblers Deviance Petty misdemeanor Introduction This chapter explores and describes the founda- tions of American criminal law. While progressing From the genesis of time, human beings have sought through its content, readers are informed of the to establish guidelines to govern human behavior. In extent to which serious crime occurs in America. ancient civilizations, rules were derived from morals, Readers will also develop an appreciation for the customs, and norms existing within society. Thus, in Republic form of government used in this nation most societies, modern laws evolved from a loose and how social contract theory guides the construc- set of guidelines into a formal system of written tion of criminal law. -

Case: 09-41064 Document: 00511425053 Page: 1 Date Filed: 03/25/2011

Case: 09-41064 Document: 00511425053 Page: 1 Date Filed: 03/25/2011 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS United States Court of Appeals FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT Fifth Circuit F I L E D March 25, 2011 No. 09-41064 Lyle W. Cayce Clerk UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff–Appellee, v. THOMAS GORE, Defendant–Appellant. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Texas Before HIGGINBOTHAM, CLEMENT, and OWEN, Circuit Judges. PRISCILLA R. OWEN, Circuit Judge: In this direct appeal Thomas Gore contends that his prior Texas conviction for conspiracy to commit aggravated robbery is not a violent felony within the meaning of the Armed Career Criminal Act (ACCA)1 and that the district court erred in sentencing him as a career offender. We affirm. I Gore pled guilty to possessing a firearm after being convicted of a felony, in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 922(g). The presentence report recommended that the 1 18 U.S.C. § 924(e). Case: 09-41064 Document: 00511425053 Page: 2 Date Filed: 03/25/2011 No. 09-41064 district court sentence Gore as a career offender pursuant to the ACCA based on Gore’s three prior state convictions, two for serious drug offenses and the other for conspiracy to commit aggravated robbery. Gore objected to the presentence report, arguing that conspiracy to commit aggravated robbery is not a violent felony under the ACCA and that he therefore should be sentenced within a Guidelines range of 33-41 months of imprisonment. The district court overruled the objection and sentenced Gore to 180 months of imprisonment. -

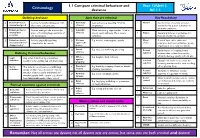

1.1 Compare Criminal Behaviour and Deviance

1.1 Compare criminal behaviour and Year 12/Unit 2. Criminology deviance AC 1.1 Defining deviance Acts that are criminal Key Vocabulary 1 Behaviour that is Such as heroically risking your own 1 Summary Less serious e.g. speeding. Tried by 1 Norms Specific rules or socially accepted unusual and good life to save someone else. offences magistrates. standards that govern behaviour in particular situations. 2 Behaviour that is Such as talking to the trees in the 2 Indictable More serious e.g. rape/murder. Tried in unusual and park, or hoarding huge quantities of offences crown court with jury. More severe 2 Values General principles or guidelines for eccentric old newspapers. sentences. how we should live our lives. 3 Behaviour that is Such as physically attacking 3 Violence E.g. murder, manslaughter, assault 3 Moral A set of basic rules, values and unusual and bad or someone for no reason. against the codes prinicples, held by an individual, group, disapproved of person organisation or society as a whole. 4 Sexual E.g. rape, sex trafficking, grooming. 4 Formal Punishments for breaking formal offences Defining Criminal behaviour sanction written rules or laws. Imposed by Offences official bodies e.g. courts, schools etc. Legal Any action forbidden by criminal law – 5 E.g. burglary, theft, robbery. 1 against definition 5 Informal Disapproval shown to a person for usually involves actus rea and mens rea property sanction breaking unwritten rules, such as telling 2 Social This includes consideration of differing 6 Fraud and E.g. frauds by company directors, benefit off or ignoring them. -

Criminal Law: Conspiracy to Defraud

CRIMINAL LAW: CONSPIRACY TO DEFRAUD LAW COMMISSION LAW COM No 228 The Law Commission (LAW COM. No. 228) CRIMINAL LAW: CONSPIRACY TO DEFRAUD Item 5 of the Fourth Programme of Law Reform: Criminal Law Laid before Parliament bj the Lord High Chancellor pursuant to sc :tion 3(2) of the Law Commissions Act 1965 Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 6 December 1994 LONDON: 11 HMSO E10.85 net The Law Commission was set up by section 1 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. The Commissioners are: The Honourable Mr Justice Brooke, Chairman Professor Andrew Burrows Miss Diana Faber Mr Charles Harpum Mr Stephen Silber QC The Secretary of the Law Commission is Mr Michael Sayers and its offices are at Conquest House, 37-38 John Street, Theobalds Road, London, WClN 2BQ. 11 LAW COMMISSION CRIMINAL LAW: CONSPIRACY TO DEFRAUD CONTENTS Paragraph Page PART I: INTRODUCTION 1.1 1 A. Background to the report 1. Our work on conspiracy generally 1.2 1 2. Restrictions on charging conspiracy to defraud following the Criminal Law Act 1977 1.8 3 3. The Roskill Report 1.10 4 4. The statutory reversal of Ayres 1.11 4 5. Law Commission Working Paper No 104 1.12 5 6. Developments in the law after publication of Working Paper No 104 1.13 6 7. Our subsequent work on the project 1.14 6 B. A general review of dishonesty offences 1.16 7 C. Summary of our conclusions 1.20 9 D. -

Criminal Code 2003.Pmd 273 11/27/2004, 12:35 PM 274 No

273 No. 9 ] Criminal Code [2004. SAINT LUCIA ______ No. 9 of 2004 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS CHAPTER ONE General Provisions PART I PRELIMINARY Section 1. Short title 2. Commencement 3. Application of Code 4. General construction of Code 5. Common law procedure to apply where necessary 6. Interpretation PART II JUSTIFICATIONS AND EXCUSES 7. Claim of right 8. Consent by deceit or duress void 9. Consent void by incapacity 10. Consent by mistake of fact 11. Consent by exercise of undue authority 12. Consent by person in authority not given in good faith 13. Exercise of authority 14. Explanation of authority 15. Invalid consent not prejudicial 16. Extent of justification 17. Consent to fight cannot justify harm 18. Consent to killing unjustifiable 19. Consent to harm or wound 20. Medical or surgical treatment must be proper 21. Medical or surgical or other force to minors or others in custody 22. Use of force, where person unable to consent 23. Revocation annuls consent 24. Ignorance or mistake of fact criminal code 2003.pmd 273 11/27/2004, 12:35 PM 274 No. 9 ] Criminal Code [2004. 25. Ignorance of law no excuse 26. Age of criminal responsibility 27. Presumption of mental disorder 28. Intoxication, when an excuse 29. Aider may justify same force as person aided 30. Arrest with or without process for crime 31. Arrest, etc., other than for indictable offence 32. Bona fide assistant and correctional officer 33. Bona fide execution of defective warrant or process 34. Reasonable use of force in self-defence 35. Defence of property, possession of right 36. -

"Judicial Corruption"

16/06/2017 Gmail - "JUDICIAL CORRUPTION" William Finnerty <[email protected]> "JUDICIAL CORRUPTION" William Finnerty <[email protected]> Fri, Jun 16, 2017 at 3:10 PM To: "First Minister of Northern Ireland Arlene Foster LL.B. MLA" <[email protected]>, [email protected], "Northern Ireland Justice Department, Case Ref: COR/1248/2016" <private.office@justice- ni.x.gsi.gov.uk>, Northern Ireland Justice Minister Claire Sugden MLA <[email protected]>, Northern Ireland Minister For Finance Máirtín Ó Muilleoir MLA <[email protected]>, Northern Ireland Minister for Health Michelle O'Neill MLA <[email protected]>, [email protected], "Lawyer Paul J. O'Kane LL.B." <[email protected]>, "Lawyer Aoife McShane LL.B." <[email protected]>, Lawyer Rory McShane <[email protected]>, Lawyer Mary Doherty <[email protected]>, "Lawyer Ronan McGuigan, LL.B. Solicitor Advocate" <[email protected]>, "Lawyer Jacqueline Malone LL.B. Solicitor Advocate" <[email protected]>, "Lawyer Louise Moley LL.B." <[email protected]>, "Lawyer Ann Marie Featherstone LL.B. LL.M." <[email protected]>, Sheila McGuigan <[email protected]>, McGuigan Malone Solicitors <[email protected]>, "Lawyer Ronan Haughey of ML White Solicitors Ltd, Newry, Northern Ireland" <[email protected]>, "John Mackell, Director of Client (Solicitor) -

Crime Prevention Division, Portland Police Bureau FACT and FICTION About Crime in Oregon August, 1979

If you have. \ issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. - -• / FACT AriD FICTION ABOUTCAIME IN OREGON '( \ PAI:PAAED BY TI1E OREGON LAW EnFORCEMErtT COUrtCIL • ------ - -- - ----- Cover design by Steve Minnick, Graphics Illustrator Crime Prevention Division, Portland Police Bureau FACT AND FICTION About Crime in Oregon August, 1979 Victor R. Atiyeh Governor "lames Brown Keith A. Stubblefield Chairman Administrator This study was supported in part by grants from the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration of the U.S. Department of Justice and the Mid-Willamette Valley Manpower Consortium. Point~ of view or opinions stated are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S. Department of Justice. ---------- ------- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors of this report are: Annie Monk Pamela Erickson Gervais Administrative Assistant and Planning and Data Analysis P1annlng and Data Analysis Unit Unit Supervisor Sincere appreciation is extended to all those whose valuable suggestions and information contributed greatly to this publication: Bob Watson, Administrator - Oregon Corrections Division Steve Cleveland, Chief Planner - Mid Wi11amette Valley COG Bill Cogswell, Chairman and Ira Blalock, Member - State Board of Parole Craig Van and Marcelle Robinson - Hillcrest School of Oregon Jeff Barnes, Director - Regional Automated Information Network Chuck Foster, Inst'~uctor - Chemeketa Conmunity College Jerry Winter, Deputy Administr'ator - Trial Court Services Cal Steward, School Liaison - Salem Police Department Lt. Tom Potter, Crime Prevention Division - Portland Police Bureau Wendy Gordon, Host/Producer - Mid-Morning, KOIN-TV Lt. Penny Orazettl, Planning & Research - Portland Police Bureau Chief Ro11ie Pean - Coos Bay Police Department Judge Irving Steinbock - Multnomah County Circuit Court Chief Jim Jones - Ontario Police Department Sheriff Jim Heenan - Marion County Sheriff's Office Karel Hyer, Academy Programs Chief - Board on Police Standards and Training Benjamin H. -

Table of Contents Crimes of Obsession: Harassment, Menacing, Stalking and Contempt by Tim Franczyk, Esq. Title Page Introduction

Table of Contents Crimes of Obsession: Harassment, Menacing, Stalking and Contempt By Tim Franczyk, Esq. Title Page Introduction 2 Categories of Stalkers 2 Legal Response 3 Degrees of Offensive Conduct 3 Relevant Statutes 3 Harassment 2nd Degree 3 Harassment 1st Degree 4 Menacing 3rd Degree 5 Menacing 2nd Degree 6 Menacing 1st Degree 7 Stalking Offenses 7 Stalking 4th Degree 7 Stalking 3rd Degree 8 Stalking 2nd Degree 8 Some Cases 9 Stalking 1st Degree 11 Criminal Contempt Offenses 11 Criminal Contempt 2nd Degree 12 Criminal Contempt 1st Degree 12 Some Cases 13 Aggravated Criminal Contempt 14 Dial M for Mayhem 14 Aggravated Harassment 2nd Degree 14 Aggravated Harassment 1st Degree 16 Final Thought 17 1 | P a g e CRIMES OF OBSESSION: HARASSMENT, MENACING, STALKING AND CONTEMPT Thomas P. Franczyk Deputy for Legal Education Assigned Counsel Program July 2nd, 2021 INTRODUCTION: In 1983, Gordon Sumner (better known as Sting) wrote one of his biggest hits which, for all intents and purposes, was an ode to obsession. In the opening verse, he writes: “Every breath you take. Every move you make. Every bond you break, every step you take, I’ll be watching you. Every single day, every word you say, every game you play, every night you stay, I’ll be watching you.” The chorus, which screams of unbridled possessiveness, asks: “Oh can’t you see, you belong to me. How my poor hear aches with every step you take. And every move you make, every vow you break, every side you take, every claim you stake, I’ll be watching you.” The character in the song (which Sumner reportedly wrote after the break-up with his first wife), would arguably fit right into the category of “rejected stalker.” This is a character described by psychologist/ New York University professor Robert T. -

Misdemeanor Crimes of Domestic Violence Revised 2014

State Statutes: Misdemeanor Crimes of Domestic Violence Revised 2014 National Center on Protection Orders and Full Faith & Credit 1901 North Fort Myer Drive, Suite 1011 Arlington, Virginia 22209 Toll Free: (800) 903-0111, prompt 2 Direct: (703) 312-7922 Fax: (703) 312-7966 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.fullfaithandcredit.org State statutes are constantly changing. Please independently verify the information found in this document. If you have a correction or update, please contact us at (800) 903-0111, prompt 2 or via email at [email protected]. This project is supported by Grant No. 2011-TA-AX-K080 awarded by the Office on Violence Against Women, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions, findings, conclusions, and recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of Justice, Office on Violence Against Women. Compiled by the National Center on Protection Orders and Full Faith & Credit TABLE OF CONTENTS NOTE: For your convenience, hyperlinks are located on each state name in this Table of Contents. For faster access, please select the name of the state you would like to view ALABAMA .................................................................................... 3 MONTANA ................................................................................. 24 ALASKA ....................................................................................... 3 NEBRASKA ................................................................................ -

Pedestrian Safety on Rural Highways

FHWA-SA-04-008 September 2004 Technical Report Pedestrian Safety on Rural Highways Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. FHWA-SA-04-008 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date (Update) Pedestrian Safety on Rural Highways September 2004 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Written By 8. Performing Organization Report No. J. W. Hall, J. D. Brogan, and M. Kondreddi 9. Performing Organization Name and Address (Update Report) 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Department of Civil Engineering, MSC01 1070 University of New Mexico 11. Contract or Grant No. Albuquerque, NM 87131-0001. 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Federal Highway Administration Office of Safety 400 Seventh Street SW Washington, DC 20590 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 15. Supplementary Notes AOTR: D. Smith (HSA-30); T. Redmon (HSA-20); 16. Abstract Although pedestrian fatalities have decreased by 16 percent over the past decade, the United States experienced nearly 4,749 pedestrian fatalities in 2003. The conventional wisdom has been that this is primarily an urban problem, where pedestrians are subject to numerous conflicts with vehicular traffic. The fact that 28 percent of pedestrian fatalities occur in rural areas has largely been ignored, despite the fact that pedestrian impacts in rural areas, while relatively rare, are much more likely to result in fatalities or serious injuries. The research described in this paper sought to identify the characteristics of rural pedestrian fatalities in ten states with above-average rates of rural pedestrian fatalities. The most prominent characteristics of rural pedestrian fatalities in these states were clear weather, hours of darkness, weekends, non- intersection locations, and level, straight roads. -

Highway Safety Act of 1973

* * PEDESTRIAN AND BICYCLE SAFETY STUDY Highway Safety Act of 1973 * (Section 214) Of T t ^. STATES Of a^ * MARCH 1975 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION NATIONAL HIGHWAY TRAFFIC SAFETY * ADMINISTRATION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20590 * PEDESTRIAN AND BICYCLE SAFETY STUDY Highway Safety Act of 1973 (Section 214) MARCH 1975 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION NATIONAL HIGHWAY TRAFFIC SAFETY ADMINISTRATION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20590 CONTENTS Page SECTION I: SYNOPSIS A. Introduction .............................................. 1 B. Executive Summary ......................................... 2 C. Background .............................................. 4 D. Study Methodology ......................................... 7 E. Congressional Recommendations ................................ 12 SECTION II: PEDESTRIAN SAFETY Introduction .............................................. 13 A. Review and Evaluation of State and Local Ordinances, Regulations, and Laws Pertaining to Pedestrian Safety .................................. 14 B. Review and Evaluation of Enforcement Policies, Procedures, Methods, Practices and Capabilities for Enforcing Pedestrian Rules ................ 35 C. Relationship Between Alcohol and Pedestrian Safety ................... 36 D. Evaluation of Ways and Means of Improving Pedestrian Safety Programs ...... 43 E. Analysis of Present Funding Allocation of Pedestrian Safety Programs and an Assessment of the Capabilities of Federal, State and Local Governments to Fund Such Activities and Programs .................... 45 F. Findings ................................................59