Offences Against Public Order

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

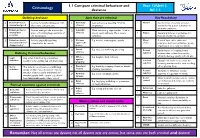

1.1 Compare Criminal Behaviour and Deviance

1.1 Compare criminal behaviour and Year 12/Unit 2. Criminology deviance AC 1.1 Defining deviance Acts that are criminal Key Vocabulary 1 Behaviour that is Such as heroically risking your own 1 Summary Less serious e.g. speeding. Tried by 1 Norms Specific rules or socially accepted unusual and good life to save someone else. offences magistrates. standards that govern behaviour in particular situations. 2 Behaviour that is Such as talking to the trees in the 2 Indictable More serious e.g. rape/murder. Tried in unusual and park, or hoarding huge quantities of offences crown court with jury. More severe 2 Values General principles or guidelines for eccentric old newspapers. sentences. how we should live our lives. 3 Behaviour that is Such as physically attacking 3 Violence E.g. murder, manslaughter, assault 3 Moral A set of basic rules, values and unusual and bad or someone for no reason. against the codes prinicples, held by an individual, group, disapproved of person organisation or society as a whole. 4 Sexual E.g. rape, sex trafficking, grooming. 4 Formal Punishments for breaking formal offences Defining Criminal behaviour sanction written rules or laws. Imposed by Offences official bodies e.g. courts, schools etc. Legal Any action forbidden by criminal law – 5 E.g. burglary, theft, robbery. 1 against definition 5 Informal Disapproval shown to a person for usually involves actus rea and mens rea property sanction breaking unwritten rules, such as telling 2 Social This includes consideration of differing 6 Fraud and E.g. frauds by company directors, benefit off or ignoring them. -

Criminal Law: Conspiracy to Defraud

CRIMINAL LAW: CONSPIRACY TO DEFRAUD LAW COMMISSION LAW COM No 228 The Law Commission (LAW COM. No. 228) CRIMINAL LAW: CONSPIRACY TO DEFRAUD Item 5 of the Fourth Programme of Law Reform: Criminal Law Laid before Parliament bj the Lord High Chancellor pursuant to sc :tion 3(2) of the Law Commissions Act 1965 Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 6 December 1994 LONDON: 11 HMSO E10.85 net The Law Commission was set up by section 1 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. The Commissioners are: The Honourable Mr Justice Brooke, Chairman Professor Andrew Burrows Miss Diana Faber Mr Charles Harpum Mr Stephen Silber QC The Secretary of the Law Commission is Mr Michael Sayers and its offices are at Conquest House, 37-38 John Street, Theobalds Road, London, WClN 2BQ. 11 LAW COMMISSION CRIMINAL LAW: CONSPIRACY TO DEFRAUD CONTENTS Paragraph Page PART I: INTRODUCTION 1.1 1 A. Background to the report 1. Our work on conspiracy generally 1.2 1 2. Restrictions on charging conspiracy to defraud following the Criminal Law Act 1977 1.8 3 3. The Roskill Report 1.10 4 4. The statutory reversal of Ayres 1.11 4 5. Law Commission Working Paper No 104 1.12 5 6. Developments in the law after publication of Working Paper No 104 1.13 6 7. Our subsequent work on the project 1.14 6 B. A general review of dishonesty offences 1.16 7 C. Summary of our conclusions 1.20 9 D. -

Criminal Code 2003.Pmd 273 11/27/2004, 12:35 PM 274 No

273 No. 9 ] Criminal Code [2004. SAINT LUCIA ______ No. 9 of 2004 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS CHAPTER ONE General Provisions PART I PRELIMINARY Section 1. Short title 2. Commencement 3. Application of Code 4. General construction of Code 5. Common law procedure to apply where necessary 6. Interpretation PART II JUSTIFICATIONS AND EXCUSES 7. Claim of right 8. Consent by deceit or duress void 9. Consent void by incapacity 10. Consent by mistake of fact 11. Consent by exercise of undue authority 12. Consent by person in authority not given in good faith 13. Exercise of authority 14. Explanation of authority 15. Invalid consent not prejudicial 16. Extent of justification 17. Consent to fight cannot justify harm 18. Consent to killing unjustifiable 19. Consent to harm or wound 20. Medical or surgical treatment must be proper 21. Medical or surgical or other force to minors or others in custody 22. Use of force, where person unable to consent 23. Revocation annuls consent 24. Ignorance or mistake of fact criminal code 2003.pmd 273 11/27/2004, 12:35 PM 274 No. 9 ] Criminal Code [2004. 25. Ignorance of law no excuse 26. Age of criminal responsibility 27. Presumption of mental disorder 28. Intoxication, when an excuse 29. Aider may justify same force as person aided 30. Arrest with or without process for crime 31. Arrest, etc., other than for indictable offence 32. Bona fide assistant and correctional officer 33. Bona fide execution of defective warrant or process 34. Reasonable use of force in self-defence 35. Defence of property, possession of right 36. -

Future Identities: Changing Identities in the UK – the Next 10 Years DR 19: Identity Related Crime in the UK David S

Future Identities: Changing identities in the UK – the next 10 years DR 19: Identity Related Crime in the UK David S. Wall Durham University January 2013 This review has been commissioned as part of the UK Government’s Foresight project, Future Identities: Changing identities in the UK – the next 10 years. The views expressed do not represent policy of any government or organisation DR19 Identity Related Crime in the UK Contents Identity Related Crime in the UK ............................................................................................................ 3 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Identity Theft (theft of personal information) .................................................................................... 6 3. Creating a false identity ...................................................................................................................... 9 4. Committing Identity Fraud ................................................................................................................ 12 5. New forms of identity crime ............................................................................................................. 14 6. The law and identity crime................................................................................................................ 16 7. Conclusions ...................................................................................................................................... -

Combatting Online Harassment and Abuse: a Legal Guide for Journalists in England and Wales

MLA Safety Guide COMBATTING ONLINE HARASSMENT AND ABUSE: A LEGAL GUIDE FOR JOURNALISTS IN ENGLAND AND WALES June 2021 DISCLAIMER: This guide is for educational purposes only. Every situation is different. A person experiencing an online safety threat should listen to their instincts, discuss their concerns with trusted allies and experts in law enforcement or security. This guide is and should not be relied upon as legal advice. Specialist legal advice should be sought based upon the particular circumstances in which it is needed. 1 MLA Safety Guide Acknowledgements This guide has been written by Beth Grossman, a barrister at Doughty Street Chambers specialising in media law. Strategic input has been provided by Caoilfhionn Gallagher QC, a leading expert in international human rights law and the safety of journalists. This guide draws upon her experience of having advised and assisted journalists dealing with online harassment and fearing for their safety. The guide was commissioned by the Media Lawyers’ Association (MLA) and the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). The DCMS commissioned this report as part of its commitment to the National Action Plan for Journalists’ Safety. However, the guide is entirely independent of the DCMS. The MLA is an association of in-house media lawyers from newspapers, magazines, book publishers, broadcasters and news agencies. It was formed to promote and protect freedom of expression, and the right to receive and impart information, opinions and ideas. Its members include in-house lawyers from all of the major UK publishers and broadcasters as well as international news organisations. Our thanks go to Cian Murphy,Sophie Argent, Zoe Norden and John Battle for their assistance with the preparation of this guide. -

Issues Paper on Cyber-Crime Affecting Personal Safety, Privacy and Reputation Including Cyber-Bullying (LRC IP 6-2014)

Issues Paper on Cyber-crime affecting personal safety, privacy and reputation including cyber-bullying (LRC IP 6-2014) BACKGROUND TO THIS ISSUES PAPER AND THE QUESTIONS RAISED This Issues Paper forms part of the Commission’s Fourth Programme of Law Reform,1 which includes a project to review the law on cyber-crime affecting personal safety, privacy and reputation including cyber-bullying. The criminal law is important in this area, particularly as a deterrent, but civil remedies, including “take-down” orders, are also significant because victims of cyber-harassment need fast remedies once material has been posted online.2 The Commission seeks the views of interested parties on the following 5 issues. 1. Whether the harassment offence in section 10 of the Non-Fatal Offences Against the Person Act 1997 should be amended to incorporate a specific reference to cyber-harassment, including indirect cyber-harassment (the questions for which are on page 13); 2. Whether there should be an offence that involves a single serious interference, through cyber technology, with another person’s privacy (the questions for which are on page 23); 3. Whether current law on hate crime adequately addresses activity that uses cyber technology and social media (the questions for which are on page 26); 4. Whether current penalties for offences which can apply to cyber-harassment and related behaviour are adequate (the questions for which are on page 28); 5. The adequacy of civil law remedies to protect against cyber-harassment and to safeguard the right to privacy (the questions for which are on page 35); Cyber-harassment and other harmful cyber communications The emergence of cyber technology has transformed how we communicate with others. -

Stuart Dingle YEAR of CALL: 2011

Stuart Dingle YEAR OF CALL: 2011 EXPERTISE Stuart undertakes criminal defence and prosecution work. He has defended in a wide range of cases, including section 18 GBHs, Fraud, trading standards infringements, aggravated burglaries, knifepoint robberies, violent disorder, indecent images, and violence including threats to kill. Stuart has a successful appellate practice and has had his cases referenced in Blackstones. Stuart defends in POCA proceedings and complex VAT/excise frauds. Stuart has particular experience of football disorder and defending against the imposition of Football Banning Orders. As well as representing private individuals Stuart has appeared on behalf of many fan support groups and travels across the country to represent fans in both Criminal cases and civil orders. Before his independent practice Stuart worked as a litigator and clerk, working on several multi-handed murders. Stuart has particular experience of considering pathological evidence. Stuart has successfully prosecuted and defended in a number of cases involving expert evidence and the consideration and cross examining of experts, including private driving, cell site, and medical causation evidence. Stuart is currently a Level 2 Panel Advocate for the CPS, and his casework includes specialist experience in domestic violence prosecution and advice. Stuart is also regularly instructed by the serious fraud division to deal with revenue, benefit and complex fraud cases. Stuart has experience advancing special hardship arguments to retain driving licences and has been sought to give advice on a variety of matters relating to driving law. In addition to crime and associated matters, Stuart also regular appears for quasi-criminal and regulatory matters including contested Football Banning Orders and Sexual Risk Orders. -

Hate Crime: the Case for Extending the Existing Offences

Hate Crime: the Case for Extending the Existing Offences Law Commission Consultation Paper No 213 Presentation will cover: • ambit of consultation - terms of reference • background - current hate crime regime, E&W law • provisional proposals, reform options, key questions Hate crime offences 2 sets of “hate crime” offences • Aggravated offences: higher maximum sentences where crime involved hostility based on race or religion - Crime and Disorder Act 1998 • Offences of stirring up hatred on grounds of race, religion and sexual orientation - Public Order Act 1986 What is “hate crime”? For police and CPS “hate crime” is any offence perceived by V or another person as motivated by hostility or prejudice based on: • Race • Religion • Sexual orientation • Disability • Transgender identity • (goths, street workers, other regional variations) • Aggravated offences don’t go this wide Statistics – Home Office In 2011/12 there were 43,748 crimes recorded by the police in England and Wales as “hate crimes” – 35,816 (82%) involved race – 1,621 (4%) involved religion – 1,744 (4%) involved disability – 4,252 (10%) involved sexual orientation – 315 (1%) involved transgender (Source: Home Office “Hate Crimes, England and Wales 2011/12”) Terms of reference MOJ asked the Law Commission to look into: “(a) extending the aggravated offences in the Crime and Disorder Act 1998 to include where hostility is demonstrated towards people on the grounds of disability, sexual orientation or [trans] gender identity; (b) the case for extending the stirring up of hatred -

Colin Banham Crime

Colin Banham Crime Colin has over 17 years’ experience both defending and prosecuting in the criminal courts. He has been instructed as a leading Junior, led Junior and acting alone in serious and complex criminal allegations. He regularly defends and prosecutes cases including aggravated burglary, grievous bodily harm with intent, violent disorder, drugs conspiracies, robbery and large-scale fraud. Colin is graded by the CPS as a Level 4 Prosecutor and is a member of the Specialist Panels for Fraud (including fiscal fraud) and Serious Year of Call: 1999 Crime (including terrorism). Clerks Colin has extensive experience in serious road traffic offences. He is regularly instructed by insurers to represent defendants, particularly in Senior Practice Manager cases involving serious injury with underlying civil litigation. He accepts Andrew Trotter private instructions in all forms of motoring offences either directly or by referral. Chief Executive & Director of Clerking RECENT CASES Tony McDaid R v RS, DB & KM (2016): Instructed by the NCA in a multi-handed Contact a Clerk conspiracy to supply Class A drugs amounting to £50.4m. The case Tel: +44 (0) 845 210 5555 was conducted against a silk and two leading juniors. Fax: +44 (0) 121 606 1501 [email protected] R v KS-R (2016): Case involving allegations of causing serious injury by dangerous driving. R v CP (2016): Successfully defending a middle-aged lady alleged to have defrauded a pension scheme. R v ZN (2016): Defending a male alleged to have conspired to import a large amount of Khat into the UK. R v AB, PB & AE (2016): Prosecuting an allegation of conspiracy to supply cannabis amounting to almost £500,000. -

Scrap the Act: the Case for Repealing the Vagrancy Act (1824)

Scrap the Act: The case for repealing the Vagrancy Act (1824) This campaign is supported by: ii Scrap the Act: The case for repealing the Vagrancy Act (1824) iii Author Acknowledgements Nick Morris works in the Policy and External Affairs The views in this report are those of Crisis only but in the course of writing directorate at Crisis. it we benefited from valued contributions: • The Crisis project team: Matt Downie, Rosie Downes, Martine Martin, Simon Trevethick, Cuchulainn Sutton-Hamilton, and Nick Morris; and our colleague Lily Holman-Brant for helping produce this report. • George Olney from Crisis for providing the stories told to him by people on the street who were affected by the Act and directors from the Crisis Skylight services across England and Wales who shared their contacts and stories. • Campaign partners Homeless Link, St Mungo’s, Centrepoint, Cymorth Cymru, The Wallich, and Shelter Cymru for their help developing this report and the campaign to repeal the Act. • Lord Hogan-Howe for this report’s foreword and for chairing the multi- agency roundtable discussion in April 2019 in the UK Supreme Court (details in Appendix 1). Photo credit Chris McAndrew, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported licence. • Mike Schwarz, Bindmans LLP, for giving the legal advice in Appendix 2. • Professor Nick Crowson for sharing historical data about the Vagrancy Act’s use. • Cllr Ruth Bush and Matthias Kelly QC, for sharing their experiences of the End the Vagrancy Act campaign. • Prison Reform Trust for helping analyse the recent data. • Hannah Hart for providing advice and connections to policing and Crown Prosecution Service contacts who briefed us on police and criminal justice processes. -

Rules in Relation to Disclosure of Spent Convictions

A Summary of the Changes in Relation to Disclosure of Spent Convictions The Key Change to the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act 1974: The removal of the legal requirement for all spent convictions to be self-disclosed by an individual so as to ensure only relevant spent convictions are required to be self-disclosed. In other words, the amendment Order restricts the requirement for self-disclosure. Unspent Convictions The disclosure of unspent convictions will not change. Spent Convictions The disclosure of certain spent conviction information will change. The decision about whether or not a spent conviction should be disclosed will be determined by the Legal Adviser prior to the Committee hearing. As the rules are prescriptive there is no need for either the Committee or the Legal Adviser to exercise discretion. A spent conviction will be disclosed or it will not. The disclosure of spent convictions will be determined by reference to one of three categories: Category 1 – Offences which must always be disclosed (Appendix 1 list) A list of such offences which must always be disclosed has been developed. It is generally offences that are more serious in nature. The list is prescriptive. Category 2 – Offences which are to be disclosed subject to rules (‘the rules list’) (Appendix 2 list) Again a prescriptive list of offences has been developed for this category. If an offence is on this list then consideration will be given to the age of the conviction and the age of the person at the time of conviction. The following table relates to convictions on the ‘rules list’ Age at Conviction Period of disclosure Treatment 18 years or older 15 years No disclosure after 15 years Younger than 18 years 7.5 years No disclosure after 7.5 years This means that a conviction on the ‘rules list’ will not be disclosed if it is over 15 years old for adults or 7.5 years for people aged under 18 years when convicted. -

Statistical Bulletin: Public Order Offences

STATISTICAL BULLETIN: PUBLIC ORDER OFFENCES Introduction This bulletin provides information on volumes and sentence outcomes for adult offenders1 sentenced for offences covered by the Sentencing Council’s draft public order offences guideline. The draft guideline covers offences under the Public Order Act 1986. In addition, the racially and religiously aggravated public order offences are provided for by s31 of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998. The Court Proceedings Database (CPD), maintained by the Ministry of Justice (MoJ), is the data source for this bulletin. Additional figures covering sentencing trends since 2006 and the demographics of offenders sentenced for public order offences are available to download as an Excel spreadsheet at the following link: http://www.sentencingcouncil.org.uk/publications/?type=publications&s&cat=statistical-bulletin Contents Summary ......................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Section 1: Riot ................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Section 2: Violent disorder ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Section 3: Affray ............................................................................................................................................................