Arxiv:1111.5599V1 [Astro-Ph.EP]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20120016986.Pdf

CIRS AND CIRS-LITE AS DESIGNED FOR THE OUTER PLANETS: TSSM, EJSM, JUICE J. Brasunas\ M. Abbas2, V. Bly!, M. Edgerton!, J. Hagopian\ W. Mamakos\ A. Morell\ B. Pasquale\ W. Smith!; !NASA God dard, Greenbelt, MD; 2NASA Marshall, Huntsville, AL; 3Design Interface, Finksburg, MD. Introduction: Passive spectroscopic remote sensing of mid infrared, a rich source of molecular lines in the outer planetary atmospheres and surfaces in the thermal infrared is solar system. The FTS approach is a workhorse compared a powerful tool for obtaining information about surface and with more specialized instruments such as heterodyne mi atmospheric temperatures, composition, and dynamics (via crowave spectrometers which are more limited in wavelength the thermal wind equation). Due to its broad spectral cover range and thus the molecular constituents detectable. As age, the Fourier transform spectrometer (FTS) is particularly such it is well adapted to map temperatures, composition, suited to the exploration and discovery of molecular species. aerosols, and condensates in Titan's atmosphere and surface NASA Goddard's Cassini CIRS FTS [I] (Fig. I) has given temperatures on Enceladus. Additionally, a lighter, more us important new insights into stratospheric composition and sensitive version ofCIRS can be used to advantage in other jets on Jupiter and Saturn, the cryo-vo1cano and thermal planetary missions, and for orbital and surface lunar mis stripes on Enceladus, and the polar vortex on Titan. We sions. have designed a lightweight successor to CIRS - called CIRS-lite - with improved spectral resolution (Table I) to Details of the four key components for CIRS-lite are: separate blended spectral lines (such as occur with isotopes). -

Question Paper

British Astronomy and Astrophysics Olympiad 2018-2019 Astronomy & Astrophysics Challenge Paper September - December 2018 Instructions Time: 1 hour. Questions: Answer all questions in Sections A and B, but only one question in Section C. Marks: Marks allocated for each question are shown in brackets on the right. Working must be shown in order to get full credit, and you may find it useful to write down numerical values of any intermediate steps. Solutions: Answers and calculations are to be written on loose paper or in examination booklets. Students should ensure their name and school is clearly written on all answer sheets and pages are numbered. A standard formula booklet with standard physical constants should be supplied. Eligibility: All sixth form students (or younger) are eligible to sit any BAAO paper. Further Information about the British Astronomy and Astrophysics Olympiad This is the first paper of the British Astronomy and Astrophysics Olympiad in the 2018-2019 academic year. To progress to the next stage of the BAAO, you must take the BPhO Round 1 in November 2018, which is a general physics problem paper. Those achieving at least a Gold will be invited to take the BAAO Competition paper on Monday 21st January 2019. To be awarded the highest grade (Distinction) in this paper, it should be sat under test conditions and marked papers achieving 60% or above should be sent in to the BPhO Office in Oxford by Friday 19th October 2018. Papers sat after that date, or below that mark (i.e. Merit or Participation), should have their results recorded using the online form by Friday 7th December 2018. -

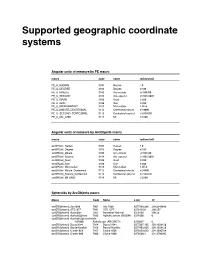

Supported Geographic Coordinate Systems

Supported geographic coordinate systems Angular units of measure by PE macro macro code name radians/unit PE_U_RADIAN 9101 Radian 1.0 PE_U_DEGREE 9102 Degree π/180 PE_U_MINUTE 9103 Arc–minute (π/180)/60 PE_U_SECOND 9104 Arc–second (π/180)/3600 PE_U_GRAD 9105 Grad π/200 PE_U_GON 9106 Gon π/200 PE_U_MICRORADIAN 9109 Microradian 1.0E-6 PE_U_MINUTE_CENTESIMAL 9112 Centesimal minute π/20000 PE_U_SECOND_CENTESIMAL 9113 Centesimal second π/2000000 PE_U_MIL_6400 9114 Mil π/3200 Angular units of measure by ArcObjects macro macro code name radians/unit esriSRUnit_Radian 9101 Radian 1.0 esriSRUnit_Degree 9102 Degree π/180 esriSRUnit_Minute 9103 Arc–minute (π/180)/60 esriSRUnit_Second 9104 Arc–second (π/180)/3600 esriSRUnit_Grad 9105 Grad π/200 esriSRUnit_Gon 9106 Gon π/200 esriSRUnit_Microradian 9109 Microradian 1.0E-6 esriSRUnit_Minute_Centesimal 9112 Centesimal minute π/20000 esriSRUnit_Second_Centesimal 9113 Centesimal second π/2000000 esriSRUnit_Mil_6400 9114 Mil π/3200 Spheroids by ArcObjects macro Macro Code Name a (m) 1/f esriSRSpheroid_Airy1830 7001 Airy 1830 6377563.396 299.3249646 esriSRSpheroid_ATS1977 7041 ATS 1977 6378135.0 298.257 esriSRSpheroid_Australian 7003 Australian National 6378160 298.25 esriSRSpheroid_AuthalicSphere 7035 Authalic sphere (WGS84) 6371000 0 esriSRSpheroid_AusthalicSphereArcInfo 107008 Authalic sph (ARC/INFO) 6370997 0 esriSRSpheroid_Bessel1841 7004 Bessel 1841 6377397.155 299.1528128 esriSRSpheroid_BesselNamibia 7006 Bessel Namibia 6377483.865 299.1528128 esriSRSpheroid_Clarke1858 7007 Clarke 1858 6378293.639 -

Perfect Little Planet Educator's Guide

Educator’s Guide Perfect Little Planet Educator’s Guide Table of Contents Vocabulary List 3 Activities for the Imagination 4 Word Search 5 Two Astronomy Games 7 A Toilet Paper Solar System Scale Model 11 The Scale of the Solar System 13 Solar System Models in Dough 15 Solar System Fact Sheet 17 2 “Perfect Little Planet” Vocabulary List Solar System Planet Asteroid Moon Comet Dwarf Planet Gas Giant "Rocky Midgets" (Terrestrial Planets) Sun Star Impact Orbit Planetary Rings Atmosphere Volcano Great Red Spot Olympus Mons Mariner Valley Acid Solar Prominence Solar Flare Ocean Earthquake Continent Plants and Animals Humans 3 Activities for the Imagination The objectives of these activities are: to learn about Earth and other planets, use language and art skills, en- courage use of libraries, and help develop creativity. The scientific accuracy of the creations may not be as im- portant as the learning, reasoning, and imagination used to construct each invention. Invent a Planet: Students may create (draw, paint, montage, build from household or classroom items, what- ever!) a planet. Does it have air? What color is its sky? Does it have ground? What is its ground made of? What is it like on this world? Invent an Alien: Students may create (draw, paint, montage, build from household items, etc.) an alien. To be fair to the alien, they should be sure to provide a way for the alien to get food (what is that food?), a way to breathe (if it needs to), ways to sense the environment, and perhaps a way to move around its planet. -

George C. Marshdll Space Flight Center Marshail S'dce Flight Center, Ahbnmd

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=19760019165 2020-03-22T13:53:19+00:00Z NASA TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM NASA TM X-73314 (NASA-TZI-X-73374) TE'IHEXED SUESATELLITE N76-26253 STUDY (NASA) 343 p HC $6.00 CSCL 22A Unclas G3,'15 42351 TETHERED SUB SATELLITE STUDY By William P. Baker, J. A. Dunltin, Zzchary J. Galaboff, Kenneth D. Johnston, Ralph R. Kissel, Mario H. Rheinful'tn, and Mathias P. L. Siebel Science and Engineering March 1976 NASA George C. Marshdll Space Flight Center Marshail S'dce Flight Center, Ahbnmd htSFC - Fcrm 1190 (Rev Junc 1971) TECHNICAL REPORT STANDARD TITLE PAGE i REPOST NO. 72.GOVERNWENT ACCESSICN NO. 3. RECIPIENT'S CATALOG NO. NASA- .. Thl X -73314 -- I 1 TITLE AN0 SUBTITLF 5. REPORT DATE March 1976 Tethered Subsateaite Study 6. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION COOE 7. aUTHOR(S) 8.PERFORMING ORGAN1 ZATION REPOI, T X See Block 15 I 3. PERFORMING CRGAHIIATIOH NAME AND ADDRESS lo. WORK UNIT, NO. - 1 George C. Marshall Space Flight Center 11. CONTRACT OR GRANT NO. Marshall Space Flight Center, Alabama 35812 - .3. TYPE OF REPOR; 8 PERIOD COVERECI 2 SPONSORING AGENCY NAME AND ADDRESS I Technical hlemorandum National Aeronautics and Space Administration Washington, D. C. 20546 1.1. SPONSORING AGENCY COOE I 5. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES, .-.-9, William p. Baker ,' J. A. Dunkin, Zachary J. ~alaboff,"':: Kenneth D. ~ohnston,'~':'~ Ralph R. Kissel?" Mario H. Rheififurth?:::: and Mathias P. L. ~iebelt Prepared by Space Sciences Laboratoly, Science ard Engineering 6. ABSTRACT This report presents the results of studies performed relating to the feasibility of deploying a subsatellite from the Shuttle by means of a tether. -

7.5 X 12 Long Title.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85371-2 - Planetary Sciences, Second Edition Imke de Pater and Jack J. Lissauer Excerpt More information 1 Introduction Socrates: Shall we set down astronomy among the subjects of study? Glaucon: I think so, to know something about the seasons, the months and the years is of use for military purposes, as well as for agriculture and for navigation. Socrates: It amuses me to see how afraid you are, lest the common herd of people should accuse you of recommending useless studies. Plato, The Republic VII The wonders of the night sky, the Moon and the Sun have systems were seen around all four giant planets. Some of fascinated mankind for many millennia. Ancient civiliza- the new discoveries have been explained, whereas others tions were particularly intrigued by several brilliant ‘stars’ remain mysterious. that move among the far more numerous ‘fixed’ (station- Four comets and six asteroids have thus far been ary) stars. The Greeks used the word πλανητηζ, meaning explored by close-up spacecraft, and there have been sev- wandering star, to refer to these objects. Old drawings and eral missions to study the Sun and the solar wind. The manuscripts by people from all over the world, such as Sun’s gravitational domain extends thousands of times the the Chinese, Greeks and Anasazi, attest to their interest in distance to the farthest known planet, Neptune. Yet the vast comets, solar eclipses and other celestial phenomena. outer regions of the Solar System are so poorly explored The Copernican–Keplerian–Galilean–Newtonian rev- that many bodies remain to be detected, possibly including olution in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries com- some of planetary size. -

Red Material on the Large Moons of Uranus: Dust from the Irregular Satellites?

Red material on the large moons of Uranus: Dust from the irregular satellites? Richard J. Cartwright1, Joshua P. Emery2, Noemi Pinilla-Alonso3, Michael P. Lucas2, Andy S. Rivkin4, and David E. Trilling5. 1Carl Sagan Center, SETI Institute; 2University of Tennessee; 3University of Central Florida; 4John Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory; 5Northern Arizona University. Abstract The large and tidally-locked “classical” moons of Uranus display longitudinal and planetocentric trends in their surface compositions. Spectrally red material has been detected primarily on the leading hemispheres of the outer moons, Titania and Oberon. Furthermore, detected H2O ice bands are stronger on the leading hemispheres of the classical satellites, and the leading/trailing asymmetry in H2O ice band strengths decreases with distance from Uranus. We hypothesize that the observed distribution of red material and trends in H2O ice band strengths results from infalling dust from Uranus’ irregular satellites. These dust particles migrate inward on slowly decaying orbits, eventually reaching the classical satellite zone, where they collide primarily with the outer moons. The latitudinal distribution of dust swept up by these moons should be fairly even across their southern and northern hemispheres. However, red material has only been detected over the southern hemispheres of these moons, during the Voyager 2 flyby of the Uranian system (subsolar latitude ~81ºS). Consequently, to test whether irregular satellite dust impacts drive the observed enhancement in reddening, we have gathered new ground-based data of the now observable northern hemispheres of these moons (sub-observer latitudes ~17 – 35ºN). Our results and analyses indicate that longitudinal and planetocentric trends in reddening and H2O ice band strengths are broadly consistent across both southern and northern latitudes of these moons, thereby supporting our hypothesis. -

Space Theme Circle Time Ideas

Space Crescent Black Space: Sub-themes Week 1: Black/Crescent EVERYWHERE! Introduction to the Milky Way/Parts of the Solar System(8 Planets, 1 dwarf planet and sun) Week 2: Continue with Planets Sun and Moon Week 3: Comets/asteroids/meteors/stars Week 4: Space travel/Exploration/Astronaut Week 5: Review Cooking Week 1: Cucumber Sandwiches Week 2: Alien Playdough Week 3: Sunshine Shake Week 4: Moon Sand Week 5: Rocket Shaped Snack Cucumber Sandwich Ingredients 1 carton (8 ounces) spreadable cream cheese 2 teaspoons ranch salad dressing mix (dry one) 12 slices mini bread 2 to 3 medium cucumbers, sliced, thinly Let the children take turns mixing the cream cheese and ranch salad dressing mix. The children can also assemble their own sandwiches. They can spread the mixture themselves on their bread with a spoon and can put the cucumbers on themselves. Sunshine Shakes Ingredients and items needed: blender; 6 ounce can of unsweetened frozen orange juice concentrate, 3/4 cup of milk, 3/4 cup of water, 1 teaspoon of vanilla and 6 ice cubes. Children should help you put the items in the blender. You blend it up and yum! Moon Sand Materials Needed: 6 cups play sand (you can purchased colored play sand as well!); 3 cups cornstarch; 1 1/2 cups of cold water. -Have the children help scoop the corn starch and water into the table and mix until smooth. -Add sand gradually. This is very pliable sand and fun! -Be sure to store in an airtight container when not in use. If it dries, ad a few tablespoons of water and mix it in. -

Irregular Satellites of the Giant Planets 411

Nicholson et al.: Irregular Satellites of the Giant Planets 411 Irregular Satellites of the Giant Planets Philip D. Nicholson Cornell University Matija Cuk University of British Columbia Scott S. Sheppard Carnegie Institution of Washington David Nesvorný Southwest Research Institute Torrence V. Johnson Jet Propulsion Laboratory The irregular satellites of the outer planets, whose population now numbers over 100, are likely to have been captured from heliocentric orbit during the early period of solar system history. They may thus constitute an intact sample of the planetesimals that accreted to form the cores of the jovian planets. Ranging in diameter from ~2 km to over 300 km, these bodies overlap the lower end of the presently known population of transneptunian objects (TNOs). Their size distributions, however, appear to be significantly shallower than that of TNOs of comparable size, suggesting either collisional evolution or a size-dependent capture probability. Several tight orbital groupings at Jupiter, supported by similarities in color, attest to a common origin followed by collisional disruption, akin to that of asteroid families. But with the limited data available to date, this does not appear to be the case at Uranus or Neptune, while the situa- tion at Saturn is unclear. Very limited spectral evidence suggests an origin of the jovian irregu- lars in the outer asteroid belt, but Saturn’s Phoebe and Neptune’s Nereid have surfaces domi- nated by water ice, suggesting an outer solar system origin. The short-term dynamics of many of the irregular satellites are dominated by large-amplitude coupled oscillations in eccentricity and inclination and offer several novel features, including secular resonances. -

Spectroscopy of Mimas, Enceladus, Tethys, and Rhea

A&A 435, 353–362 (2005) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20042482 & c ESO 2005 Astrophysics Near-infrared (0.8–4.0 µm) spectroscopy of Mimas, Enceladus, Tethys, and Rhea J. P. Emery1,,D.M.Burr2,D.P.Cruikshank3,R.H.Brown4, and J. B. Dalton5 1 NASA Ames Research Center/SETI Institute, Mail Stop 245-6, Moffett Field, CA 94035, USA e-mail: [email protected] 2 USGS Astrogeology Branch, 2255 N Gemini Dr, Flagstaff, AZ 86001, USA 3 NASA Ames Research Center, Mail Stop 245-6, Moffett Field, CA 94035, USA 4 Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, Univ. of Arizona, 1629 E. University Dr, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA 5 NASA Ames Research Center/SETI Institute, Mail Stop 245-3, Moffett Field, CA 94035, USA Received 3 December 2004 / Accepted 25 January 2005 Abstract. Spectral measurements from the ground in the time leading up to the Cassini mission at Saturn provide important context for the interpretation of the forthcoming spacecraft data. Whereas ground-based observations cannot begin to approach the spatial scales Cassini will achieve, they do possess the benefits of better spectral resolution, a broader possible time baseline, and unique veiewing geometries not obtained by spacecraft (i.e., opposition). In this spirit, we present recent NIR reflectance spectra of four icy satellites of Saturn measured with the SpeX instrument at the IRTF. These measurements cover the range 0.8–4.0 µm of both the leading and trailing sides of Tethys and the leading side of Rhea. The L-band region (2.8–4.0 µm) offers new opportunities for searches of minor components on these objects. -

The Planets -- Investigating Our Planetary Family Tree

Relative Sizes of the Planets and other Objects 3.1 The actual sizes of the major objects in our solar system range from the massive planet Jupiter, to many small moons and asteroids no more than a few kilometers across. It is often helpful to create a scaled model of the major objects so that you can better appreciate just how large or small they are compared to our Earth. This exercise will let you work with simple proportions and fractions to create a scaled-model solar system. Problem 1 - Jupiter is 7/6 the diameter of Saturn, and Saturn is 5/2 the diameter of Uranus. Expressed as a simple fraction, how big is Uranus compared to Jupiter? Problem 2 – Earth is 13/50 the diameter of Uranus. Expressed as a simple fraction, how much bigger than Earth is the planet Saturn? Problem 3 – The largest non-planet objects in our solar system, are our own Moon ( radius=1738 km), Io (1810 km), Eris (1,500 km), Europa (1480 km), Ganymede (2600 km), Callisto (2360 km), Makemake (800 km),Titan (2575 km), Triton (1350 km), Pluto (1,200 km), Haumea (950 km). Create a bar chart that orders these bodies from smallest to largest. For this sample, what is the: A) Average radius? B) Median radius? Problem 4 – Mercury is the smallest of the eight planets in our solar system. If the radius of Mercury is 2425 km, how would you create a scaled model of the non-planets if you selected a diameter for the disk of Mercury as 50 millimeters? Space Math Answer Key 3.1 Problem 1 - Jupiter is 7/6 the diameter of Saturn, and Saturn is 5/2 the diameter of Uranus. -

[email protected]

Issue No. 00 March 2007 # 2 b c ab PS News aab bdb cb cc ¢£ ¡ "! t Physical Study of Planets and Satellites The IAU Commission 16 Electronic Bulletin Edited by: R´egis Courtin [email protected] http://www.iaa.es/IAUComm16 Word from the Editor Dear Colleagues, Commission 16 of the IAU is pleased to bring you Issue N◦00 of PS2News. Thisissueservesasa’birth announcement’ for what I hope will become a monthly electronic venue for exchanging news about the Physical Study of Planets and Satellites in the Solar System, and about the various activities of the Commission. Starting with Issue N◦01, PS 2News will only be distributed to researchers who have registered them- selves on the distribution list. To do so, just send an e-mail to: [email protected] with the following subject: subscribe ps2news your-first-name your-last-name All issues will also be archived in PDF format on the Commission 16 website: http://www.iaa.es/IAUComm16 (under section PS2 News) And, of course, I am calling on your contributions for the next issue (see page 3). Best regards, R´egis Courtin President of IAU Commission 16 Editor, PS 2News Contents News& Announcements .........................................................................2 Conferences& Workshops ....................................................................... 2 BulletinInformation .............................................................................3 1 NEWS & ANNOUNCEMENTS The third dwarf planet (following Ceres and Pluto) was named by the IAU in September 2006: 2003 UB313