Seychelles Warblers: Complexities of the Helping Paradox

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Molecular Phylogeny and Phylogeography of Reed Warblers and Allies (Aves: Acrocephalidae)

Dissertation submitted to the Combined Faculties for the Natural Sciences and for Mathematics of the Ruperto-Carola University of Heidelberg, Germany for the degree of Doctor of Natural Sciences presented by Tayebeh Arbabi Born in Mashhad, Iran Oral examination: 26 June 2014 Molecular Phylogeny and Phylogeography of Reed Warblers and Allies (Aves: Acrocephalidae) Referees: Prof. Dr. Michael Wink Prof. Dr. Marcus Koch i Table of contents Zusammenfassung..................................................................................................................... v Summary .................................................................................................................................. vi Abbreviations ......................................................................................................................... vii Publications ........................................................................................................................... viii 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 General introduction ......................................................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Avian taxonomy ......................................................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Phylogeny and phylogeography ................................................................................. 2 1.1.3 Molecular markers .................................................................................................... -

Evolutionary and Conservation Genetics of the Seychelles Warbler ( Acrocephalus Sechellensis )

Evolutionary and conservation genetics of the Seychelles warbler ( Acrocephalus sechellensis ) David John Wright A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Biological Sciences University of East Anglia, UK May 2014 © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. This thesis is dedicated to Laura, my wife and partner-in-crime, for the endless supply of love, support, tea and cake. ii Abstract In this thesis, I investigated how evolutionary forces and conservation action interact to shape neutral and adaptive genetic variation within and among populations. To accomplish this, I studied an island species, the Seychelles warbler (Acrocephalus sechellensis ), with microsatellite markers and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) genes as measures of neutral and adaptive variation respectively. First, I used museum DNA and historical records to reveal a recent bottleneck that provides context for the contemporary genetic variation observed in this species. I then determined the impact of four translocations on genetic diversity over two decades. I found that diversity does not differ significantly between islands but the use of smaller founder sizes in two translocations has caused population divergence. These results indicate that stochastic genetic capture is important in translocations and that future assisted gene flow between populations may be necessary. As a tool for conservation practitioners, I wrote a technical report of the most recent translocation - to Frégate Island - detailing practicalities and outcomes to help inform future translocation policy. -

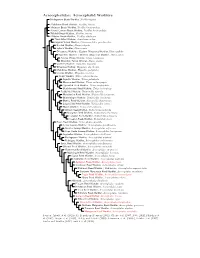

Acrocephalidae Species Tree

Acrocephalidae: Acrocephalid Warblers Madagascan Brush-Warbler, Nesillas typica ?Subdesert Brush-Warbler, Nesillas lantzii ?Anjouan Brush-Warbler, Nesillas longicaudata ?Grand Comoro Brush-Warbler, Nesillas brevicaudata ?Moheli Brush-Warbler, Nesillas mariae ?Aldabra Brush-Warbler, Nesillas aldabrana Thick-billed Warbler, Arundinax aedon Papyrus Yellow Warbler, Calamonastides gracilirostris Booted Warbler, Iduna caligata Sykes’s Warbler, Iduna rama Olivaceous Warbler / Eastern Olivaceous-Warbler, Iduna pallida Isabelline Warbler / Western Olivaceous-Warbler, Iduna opaca African Yellow Warbler, Iduna natalensis Mountain Yellow Warbler, Iduna similis Upcher’s Warbler, Hippolais languida Olive-tree Warbler, Hippolais olivetorum Melodious Warbler, Hippolais polyglotta Icterine Warbler, Hippolais icterina Sedge Warbler, Titiza schoenobaenus Aquatic Warbler, Titiza paludicola Moustached Warbler, Titiza melanopogon ?Speckled Reed-Warbler, Titiza sorghophila Black-browed Reed-Warbler, Titiza bistrigiceps Paddyfield Warbler, Notiocichla agricola Manchurian Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla tangorum Blunt-winged Warbler, Notiocichla concinens Blyth’s Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla dumetorum Large-billed Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla orina Marsh Warbler, Notiocichla palustris African Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla baeticata Mangrove Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla avicenniae Eurasian Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla scirpacea Caspian Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla fusca Basra Reed-Warbler, Acrocephalus griseldis Lesser Swamp-Warbler, Acrocephalus gracilirostris Greater Swamp-Warbler, Acrocephalus -

Morphological Variation, Plumage and Song in Pacific Island Acrocephalus Warblers

202 Notornis, 2018, Vol. 65: 202–222 0029-4470 © The Ornithological Society of New Zealand Inc. From wetlands to islands: morphological variation, plumage and song in Pacific island Acrocephalus warblers BEN D. BELL Centre for Biodiversity & Restoration Ecology, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington 6140, New Zealand Abstract: Acrocephalus warblers occur across Eurasia, Africa, and Australasia, where they are typically migratory, wetland species, but also occur on islands as sedentary endemics in drier habitats, including forest and scrub. External morphology and song amongst Pacific island Acrocephalus warblers were investigated and comparisons made with Acrocephalus species elsewhere. There was a range of sizes between Pacific island Acrocephalus warblers, many being larger than migratory continental species. Bill:wing length ratios were higher in most Pacific species, and their wings more rounded, than most continental species, but less rounded than swamp-warblers of Africa and adjacent islands. Plumages of W and N Pacific species resembled reed-warblers elsewhere, but in SE Polynesia were more varied, brown or grey dorsally, shaded olive, yellow or rufous, and pale ventrally, shaded white, yellow or buff-white, with a melanistic morph on Tahiti. Spectrographic analysis showed a gradient of song complexity from continental and Marianas/ Micronesia species (A. hiwae, A. syrinx), through to A. taiti and A. vaughani on the Pitcairn islands, which had no song. The mean frequency of Pacific island reed-warbler songs was inversely correlated with mean body size. Bell, B.D. 2018. From wetlands to islands: morphological variation, plumage and song in Pacific island Acrocephalus warblers. Notornis 65(4): 202–222. Key words: Acrocephalus, body-size, evolution, islands, Pacific, reed-warbler, song INTRODUCTION & Cibois 2017). -

Kinship and Familiarity Mitigate Costs of Social Conflict Between

Kinship and familiarity mitigate costs of social conflict PNAS PLUS between Seychelles warbler neighbors Kat Bebbingtona,b,1, Sjouke A. Kingmab, Eleanor A. Fairfielda, Hannah L. Dugdalec, Jan Komdeurb, Lewis G. Spurgina, and David S. Richardsona,d aSchool of Biological Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich NR47TJ, United Kingdom; bBehavioural Ecology and Physiology Group, Groningen Institute for Evolutionary Life Sciences, University of Groningen, 9712CP Groningen, The Netherlands; cSchool of Biology, University of Leeds, Leeds LS29JT, United Kingdom; and dNature Seychelles, Mahé, Republic of Seychelles Edited by Joan E. Strassmann, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, and approved September 6, 2017 (received for review March 15, 2017) Because virtually all organisms compete with others in their social costly (8), so cooperative maintenance of a boundary should be environment, mechanisms that reduce conflict between interacting beneficial, as it reduces the need for costly policing. Kin selection individuals are crucial for the evolution of stable families, groups, could help prevent escalated conflict over territory boundaries, and societies. Here, we tested whether costs of social conflict over but there is also a well-established mechanism by which mutu- territorial space between Seychelles warblers (Acrocephalus sechel- alistic benefits between interacting individuals could resolve lensis) are mitigated by kin-selected (genetic relatedness) or mutu- conflict. The “dear enemy” phenomenon predicts that conflict is alistic (social familiarity) mechanisms. By measuring longitudinal lower between familiar neighbors (9). This is because it is less ’ changes in individuals body mass and telomere length, we demon- costly to maintain territory boundaries with existing neighbors, strated that the fitness costs of territoriality are driven by a complex with whom agreements about territory boundaries have already interplay between relatedness, familiarity, local density, and sex. -

Kin-Recognition and Mhc-Discrimination in African Clawed Frog (Xenopus Laevis) Tadpoles

KIN RECOGNITION AND MHC DISCRIMINATION IN AFRICAN CLAWED FROG (XENOPUS LAEVIS) TADPOLES A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Zoology in the University of Canterbury by Jandouwe Villinger University of Canterbury 2007 Abstract i ABSTRACT Kin-recognition abilities, first demonstrated 25 years ago in toad tadpoles, now appear to be widespread among amphibians. In some vertebrates kin recognition is based, at least in part, on highly polymorphic major histocompatibility complex (MHC) genes. Besides protecting animals from disease resistance, MHC genes regulate social behaviour. They allow relatives to recognise one another so that they can cooperate for mutual benefit. These two seemingly distinct functions of MHC genes may be integrally related, because animals need to outbreed to optimise the immune systems of their offspring. The ability to discriminate MHC-type is therefore likely to facilitate kin discrimination in tadpoles. I tested association preferences of African clawed-frog (Xenopus laevis) tadpoles in a laboratory choice apparatus. As in other anuran species, I found that tadpoles at earlier developmental stages preferentially associate with unfamiliar siblings over unfamiliar non- siblings but that this preference reverses during development. Tadpoles approaching metamorphosis demonstrated a reversal in their preference; they preferentially school with non-kin rather than kin. The ontogenetic switch in larval schooling preferences coincides with the onset of thyroid hormone (TH) controlled development and may be indicative of decreased fitness benefits associated with schooling with kin at later developmental stages. These may result from an increase in intraspecific competition, predation, or disease susceptibilities of prometamorphic individuals. -

Chapter 7. Sex Determining Mechanisms in Vertebrates Sarah B

Chapter 7. Sex Determining Mechanisms in Vertebrates Sarah B. M. Kraak & Ido Pen 7. 1. Summary Vertebrates have various sex determining mechanisms. These have been broadly classified as either genotypic sex determination (GSD) or environmental sex determination (ESD). This terminology, however, may obscure the fact that mixtures between genotypic and environmental sex determination exist, or that genotypic and environmental sex determination may, in fact, be the extremes of a continuum. Sex ratio evolution plays an important role in the evolution of sex determining mechanisms. 7.2 Introduction This chapter starts with the proximate aspects of sex determining mechanisms (section 7.3). We introduce the traditional classification of sex determining mechanisms that exist in vertebrates (section 7.3.1) and the distribution of mechanisms among extant vertebrate taxa (section 7.3.2). At phylogenetically shallow levels, different mechanisms are present. We describe how the existence of either male or female heterogamety, or environmental sex determination is usually established for individual species or taxa (section 7.3.3). Cases of mixed sex determination, i.e. combinations of genotypic and environmental sex determination are also observed (section 7.3.4) and we caution this phenomenon has implications for sex identification by molecular markers (section 7.3.5). We stress that phenotypic sex generally has environmental and genetic components and discuss a model that attempts the unification of sex determination by stating that sex determination in all vertebrates is mediated by differential growth of the embryo (section 7.3.6). In the second part of the chapter we discuss the evolution of sex-determining mechanisms. -

Senescence of Song Revealed by a Long-Term Study of the Seychelles Warbler (Acrocephalus Sechellensis)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Groningen University of Groningen Senescence of song revealed by a long-term study of the Seychelles warbler (Acrocephalus sechellensis) Berg, Mathew L; Beebe, Sarah C; Komdeur, Jan; Cardilini, Adam P A; Ribot, Raoul F H; Bennett, Andrew T D; Buchanan, Katherine L Published in: Scientific Reports DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-77405-3 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2020 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Berg, M. L., Beebe, S. C., Komdeur, J., Cardilini, A. P. A., Ribot, R. F. H., Bennett, A. T. D., & Buchanan, K. L. (2020). Senescence of song revealed by a long-term study of the Seychelles warbler (Acrocephalus sechellensis). Scientific Reports, 10(1), [20479]. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77405-3 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. -

Translocation of the Seychelles Warbler Acrocephalus Sechellensis to Establish a New Population on Frégate Island, Seychelles

D.J. Wright, N.J. Shah & D.S. Richardson / Conservation Evidence (2014) 11, 20-24 Translocation of the Seychelles warbler Acrocephalus sechellensis to establish a new population on Frégate Island, Seychelles David J. Wright1, Nirmal J. Shah2 & David S. Richardson1,2* 1 School of Biological Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich Research Park, Norwich, Norfolk, NR4 7TJ, UK 2 Nature Seychelles, Roche Caiman, PO Box 1310, Mahé, Republic of Seychelles SUMMARY In December 2011, 59 adult Seychelles warblers Acrocephalus sechellensis were translocated between two islands in the Seychelles. Birds were captured on Cousin Island and translocated to Frégate Island using a hard release method, with minimum time in captivity. Frégate had been previously identified as a suitable host for a substantial population of Seychelles warblers, although the presence of the species had never been confirmed on this island. It was estimated that Frégate currently has the potential to support about 500 Seychelles warblers, rising to over 2,000 after habitat regeneration. All birds survived the translocation and were released unharmed at the new site within 24 hours of capture. Close monitoring of both the new and source population was undertaken over a period of 18 months. By June 2013, the Frégate population had increased to 80 individuals, which included 38 of the original translocated birds and 42 birds which had hatched on Frégate. There was also evidence that multiple generations had already hatched on the island. This shows that the Seychelles warbler responded well to a hard release translocation, with observed population growth on Frégate comparable to previous warbler translocations. -

Chapter 17 Mhc Signaling During Social Communication

CHAPTER 17 MHC SIGNALING DURING SOCIAL COMMUNICATION James S. Ruff,†* Adam C. Nelson,† Jason L. Kubinak and Wayne K. Potts Department of Biology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA †These authors contributed equally to this manuscript *Corresponding Author: James S. Ruff—Email: [email protected] Abstract: The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) has been known to play a critical role in immune recognition since the 1950s. It was a surprise, then, in the 1970s when the first report appeared indicating MHC might also function in social signaling. Since this seminal discovery, MHC signaling has been found throughout vertebrates and its known functions have expanded beyond mate choice to include a suite of behaviors from kin‑biased cooperation, parent‑progeny recognition to pregnancy block. The widespread occurrence of MHC in social signaling has revealed conserved behavioral‑genetic mechanisms that span vertebrates and includes humans. The identity of the signal’s chemical constituents and the receptors responsible for the perception of the signal have remained elusive, but recent advances have enabled the identification of the key components of the behavioral circuit. In this chapter we organize recent findings from the literature and discuss them in relation to four nonmutually exclusive models wherein MHC functions as a signal of (i) individuality, (ii) relatedness, (iii) genetic compatibility and (iv) quality. We also synthesize current mechanistic studies, showing how knowledge about the molecular basis of MHC signaling can lead to elegant and informative experimental manipulations. Finally, we discuss current evidence relating to the primordial functions of the MHC, including the possibility that its role in social signaling may be ancestral to its central role in adaptive immunity. -

Indian Ocean Islands Seychelles, Mauritius, Réunion, and Rodrigues 17Th to 28Th September 2018 (12 Days) Trip Report

Indian Ocean Islands Seychelles, Mauritius, Réunion, and Rodrigues 17th to 28th September 2018 (12 days) Trip Report Rodrigues Fody by Daniel Keith Danckwerts Tour Leader: Daniel Keith Danckwerts Rockjumper Birding Tours View more tours Trip Report – RBL Indian Ocean Islands 2018 2 Tour Summary Sprinkled through the tropical seas off the East African coast are a series of corraline, granitic and volcanic islands that, together, support an incredible 35 regional endemic birds. This includes some of the world’s rarest and most sought-after birds, including the magical Seychelles Paradise Flycatcher, indescribably rare and critically endangered Réunion Cuckooshrike, jewel-like Rodrigues and Mauritius Fodies, mythical Seychelles Scops Owl and, of course, the swift-flying Barau’s Petrel. These islands also support several million widespread breeding seabirds, including Brown and Lesser Noddies, White and Sooty Terns, both White-tailed and Red-tailed Tropicbirds, and Wedge-tailed and Tropical Shearwaters. Our 12-day journey took us across most of these isolated landmasses, where we secured sightings of an incredible 75 species, including all but one of the region’s endemics. Some of the undisputed highlights included our day trip to Cousin Island (Seychelles), where we watched several hundred thousand seabirds attending their nests, along with three endangered Seychellois endemics (Seychelles Magpie-Robin, Seychelles Warbler, and Seychelles Fody), as well as our hike through the tree-fern dominated forests of Réunion Island, where we saw all of the island’s endemics at very close range. It really was a sensational trip like no other! ____________________________________________________________________________________ The top ten birds of the trip, as decided upon by the tour participants: 1. -

Population Census and Habitat Use of Rodrigues Warbler Acrocephalus Rodericanus

Bird Conservation International (2002) 12:211–230. BirdLife International 2002 DOI: 10.1017/S0959270902002137 Printed in the United Kingdom Population census and habitat use of Rodrigues Warbler Acrocephalus rodericanus DAVE A. SHOWLER, ISABELLE M. COˆ TE´ and CARL G. JONES Summary The Endangered Rodrigues Warbler Acrocephalus rodericanus is endemic to the Indian Ocean island of Rodrigues, one of the world’s most devastated tropical islands, its native forest having been completely destroyed since human colonization three centuries ago. It is now found in thickets and woodland dominated entirely by non-native trees and shrubs. As a step to implementing conservation initiatives, a population census and habitat study was undertaken in April–June 1999. Using a combination of tape playback of song and point counts, at least 103 Rodrigues Warblers spread through nine wooded localities were observed, and a minimum population of 150 birds estimated. The majority (78%) and highest densities (2.3/ha) were found in habitat dominated by one introduced invasive tree, the rose-apple Syzygium jambos. Warblers were also found in plantations dominated by mahogany Swietenia mahagoni, tecoma Tabebuia pallida and Norfolk Island pine Araucaria cunninghamii, but at much lower densities (0.5/ha). Warbler densities were highest in habitat with a dense structure of small branches. There was a strong positive relationship between one index of human disturbance (number of cut branches) and warbler densities. This low-intensity cutting may promote the growth of new shoots thus perpetuating the dense vegetation structure that Rodrigues Warbler favours. At two localities, one supporting an existing population of warblers and the other prone to extirpation (shown from previous surveys), vegetation structure and composition were similar between sites, hinting that in some currently unoccupied areas, habitat is probably suitable and other factors are operating to preclude colonization and establishment.