Amsterdam 2013 English Population 1086 1541

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

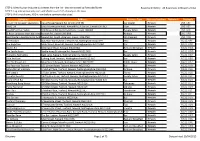

Full Property Address Primary Liable

Full Property Address Primary Liable party name 2019 Opening Balance Current Relief Current RV Write on/off net effect 119, Westborough, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 1LP The Edinburgh Woollen Mill Ltd 35249.5 71500 4 Dnc Scaffolding, 62, Gladstone Lane, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO12 7BS Dnc Scaffolding Ltd 2352 4900 Ebony House, Queen Margarets Road, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 2YH Mj Builders Scarborough Ltd 6240 Small Business Relief England 13000 Walker & Hutton Store, Main Street, Irton, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO12 4RH Walker & Hutton Scarborough Ltd 780 Small Business Relief England 1625 Halfords Ltd, Seamer Road, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO12 4DH Halfords Ltd 49300 100000 1st 2nd & 3rd Floors, 39 - 40, Queen Street, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 1HQ Yorkshire Coast Workshops Ltd 10560 DISCRETIONARY RELIEF NON PROFIT MAKING 22000 Grosmont Co-Op, Front Street, Grosmont, Whitby, North Yorkshire, YO22 5QE Grosmont Coop Society Ltd 2119.9 DISCRETIONARY RURAL RATE RELIEF 4300 Dw Engineering, Cholmley Way, Whitby, North Yorkshire, YO22 4NJ At Cowen & Son Ltd 9600 20000 17, Pier Road, Whitby, North Yorkshire, YO21 3PU John Bull Confectioners Ltd 9360 19500 62 - 63, Westborough, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 1TS Winn & Co (Yorkshire) Ltd 12000 25000 Des Winks Cars Ltd, Hopper Hill Road, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 3YF Des Winks [Cars] Ltd 85289 173000 1, Aberdeen Walk, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 1BA Thomas Of York Ltd 23400 48750 Waste Transfer Station, Seamer, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, -

Churches with Viking Stone Sculpture 53

Durham E-Theses Early ecclesiastical organization:: the evidence from North-east Yorkshire Kroebel, Christiane How to cite: Kroebel, Christiane (2003) Early ecclesiastical organization:: the evidence from North-east Yorkshire, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3183/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Albstnllct Christiane Kroebel Early Ecclesiastical Organisation: the Evidence from North-east Yorkshire MA Thesis, University of Durham, Department of History, 2003 The aim of this thesis is to discover how parishes evolved in North-east Yorkshire. It seeks the origin ofthe parish system in the 7th century with the establishment of monasteria in accordance with the theory, the 'minster' hypothesis, that these were the minsters of the Middle Ages and the ancient parish churches of today. The territory of the monasterium, its parochia, was that of the secular royal vill, because kings granted these lands with the intention that monasteries provided pastoral care to the royal vill. -

Cleveland Naturalists' Field Club

CLEVELAND NATURALISTS’ FIELD CLUB RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS 1928 TO 1932 VOL.IV. Part 2 Edited by T.A. LOFTHOUSE F.R.I.B.A., F.E.S AND M. ODLING M.A., B.SC.,F.G.S. PRICE THREE SHILLINGS (FREE TO MEMBERS) MIDDLESBROUGH; H & F STOKELD 1932 85 CONTENTS Officers Elected at the 48th – 51st Annual Meeting - 85 - 86 48th-51st Annual Reports - 87 - 94 Excavations at Eston Camp 1929 – F Elgee - 95 Field Meetings and Lectures 1928-32 - 96 - 98 History of Natural History Societies in Middlesbrough - J.W.R Punch F.R.A.S. - 99 - 106 In Memoriam J.J. Burton O.B.E., J.P., F.R.A.S J.W.R.PUNCH, F.R.A.S. -107 - 110 In Memorium H. Frankland F.I.C. E.W.Jackson F.I.C., F.G.S -110 - 111 A Few Cleveland Place Names Major R.B.Turton - 112 - 118 The Cleveland Whin Dyke J J Burton O.B.E., J.P., F.G.S.,M.I.M.E - 119 -136 Notes on Wild Flowers Chas. Postgate & M Odling - 136 Report on Cleveland Lepidoptera T.A. Lofthouse, F.E.S. - 137 – 142 Coleoptera observed in Cleveland M.L. Thompson F.E.S. - 143 - 145 A Preliminary list of Cleveland Hemiptera M.L. Thompson F.E.S. - 146 – 156 Floods in the Esk Valley July 1930 and Sept 1931 – J.W.R.Punch F.R.A.S. - 156 – 166 Ornithological Notes in Yorkshire and South Durham – C E Milburn - 167 – 171 Meteorological Observations at Marton-in- Cleveland 1928-31 – M Odling M.A.,B.SC.,F.G.S - 172 – 176 Notes on the Alum Industry – H N Wilson F.I.C. -

The National and Community Averages Being 228 And

19 . 5 . 75 Official Journal of the European Communities No L 128/231 COUNCIL DIRECTIVE of 28 April 1975 concerning the Community list of less-favoured farming areas within the meaning of Directive No 75/268/EEC (United Kingdom ) (75/276/EEC ) THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, 75% of the national average (£ 1 072 and £ 1 436 respectively); Having regard to the Treaty establishing the Euro pean Economic Community ; Whereas the index relating to the low population density referred to in Article 3 ( 4) ( c ) of Directive Having regard to Council Directive No 75/268/ No 75/268/EEC does not exceed 36 inhabitants per EEC (*) of 28 April 1975 on mountain and hill square kilometre ( the national and Community farming and farming in certain less-favoured areas , averages being 228 and 168 inhabitants per square and in particular Article 2 ( 2 ) thereof ; kilometre respectively ; whereas the minimum propor tion of the working population engaged in agriculture as a percentage of the total working population is Having regard to the proposal from the Commission ; 19% ( the national and Community averages being 3-08 and 9-58 % respectively); Having regard to the Opinion of the European Parliament ; "Whereas the nature and level of the abovementioned indices, utilized by the Government of the United Having regard to the Opinion of the Economic and Kingdom to define the areas notified to the Commis Social Committee ( 2 ); sion , corresponds to the characteristics of less favoured farming areas referred to in Article 3 (4) of Whereas the United -

The Parishes of Ugthorpe and Hutton Mulgrave Grave Parish Council

The parishes of Ugthorpe and Hutton Mulgrave Grave Parish Council. [email protected] datanorthyorkshire.gov.uk Minutes of the extraordinary meeting at 7.30pm on Tuesday 6th February 2018, at St Anne's Hall, Ugthorpe. Present: Cllr S. Brown, A. R. Clay, S. Stroyd, M. Chapman and K. Thwaite. J. Jacques -Hale, Clerk. 1. TO RECEIVE AND APPROVE APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE None 2. TO RECEIVE DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST, Members to declare any personal, pecuniary or prejudicial interests they may have in the following items that are not already declared under the Council’s Code of Conduct or member’s Register of Interests. None 3. MINUTES The minutes of Ugthorpe Group Parish Council extraordinary meeting held on 6th February, 2018 were read, agreed a correct record and signed proposed by cllr S. Brown and seconded by Cllr Stephen Stroyd. 4. MATTERS ARISING FROM PREVIOUS MEETING; To receive information on the following ongoing issues and decide further action where necessary: 4.1 Dog fouling. SBC warden to be informed, possible signs and procedures to be sought. JJH 4.2 Parking - highways - Inconsiderate parking policy. invite Rural police office to the next meeting JJH 4.3 Land slipping near Birkhead, Hutton Mulgrave - Monitoring NYCC investigating. 4.4 New minute book - ordered JJH Signed Cllr S. Brown ....................................................................... Date ............................................... 1 4.5 New parish clerk contract of employment - hours, accountant -Circulated contact to be discussed at next meeting. JJH 4.7 Quotes for laptop, scanner /printer and external hard drive, Microsoft office. Discuss with Mr Pruden & ordered Laptop & printer scanner quotes for hard drive and Microsoft R C, 4.8 Basic website costing quote 1 received. -

English Medieval Population: Reconciling Time Series and Cross Sectional Evidence

ENGLISH MEDIEVAL POPULATION: RECONCILING TIME SERIES AND CROSS SECTIONAL EVIDENCE Stephen Broadberry, London School of Economics, [email protected] Bruce M. S. Campbell, The Queen’s University of Belfast, [email protected] Bas van Leeuwen, University of Warwick, [email protected] 11 October 2011 File: MedievalPopulation8 Abstract: A new time series for English medieval population is constructed from manor-level data using an index-number approach and a regional-weighting scheme. The absolute level of the medieval population is established with a benchmark for 1377, but using the need for consistency with other benchmarks for 1086, 1522 and 1541 as additional constraints. The amount of food required to support the peak medieval population is checked against a reconstruction of English agriculture at that time. Acknowledgements: This paper forms part of the project “Reconstructing the National Income of Britain and Holland, c.1270/1500 to 1850”, funded by the Leverhulme Trust, Reference Number F/00215AR.We are grateful to Alexander Apostolides for valuable research assistance and to Larry Poos for making available his data on tithing-penny payments. 1 I. INTRODUCTION The pioneering work on English medieval population by Russell (1948) established benchmark levels of population for 1086 and 1377 and considered time-series evidence to link these to each other and to estimates for the early-modern period. Russell paid particular attention to the consistency of his estimates over this long sweep of history and arrived at the conclusion that the peak level of medieval population before the Black Death was around 3.7 million. -

CENTENARY INDEX to the TRANSACTIONS of the THOROTON SOCIETY of NOTTINGHAMSHIRE Volumes 1 - 100 1897-1997

CENTENARY INDEX To the TRANSACTIONS OF THE THOROTON SOCIETY of NOTTINGHAMSHIRE Volumes 1 - 100 1897-1997 Together with the THOROTON SOCIETY RECORD SERIES Volumes I - XL 1903-1997 and the THOROTON SOCIETY EXCAVATION SECTION Annual Reports1936-40 Compiled by LAURENCE CRAIK ã COPYRIGHT THOROTON SOCIETY AND COMPILER ISBN 0 902719 19X INTRODUCTION The Thoroton Society began to publish the 'Transactions' in 1897. This volume is intended as an Centenary index to all material published in the 'Transactions' from 1897 to 1996, to the contents of the Record Series volumes published from 1903 to 1997, and to the reports of the Excavation Section published between 1936 and 1940. Earlier indexes were published in 1951 and 1977; these are now superseded by this new Centenary index. Contents The index is in two parts: an author index, and an index to subjects, periods, and places. AUTHOR: this lists articles under the names of their authors or editors, giving the full title, volume number and page numbers. Where an article has more than one author or editor, it is listed by title under the name of each author or editor, with relevant volume and page numbers. SUBJECT: The contents of articles are indexed by subject and by place; topics of archaeological importance are also indexed by period. Cross-references are used to refer the enquirer from one form of heading to another, for example 'Abbeys' see ' Monastic houses', or from general headings such as 'Monastic houses' to the names of individual buildings. Place-names in the index are often followed by sub-headings indicating particular topics. -

Heritage at Risk Register 2010 / Yorkshire and the Humber

HERITAGE AT RISK 2010 / YORKSHIRE AND THE HUMBER Contents HERITAGE AT RISK 3 Reducing the risks 6 Publications and guidance 9 THE REGISTER 11 Content and assessment criteria 11 Key to the entries 13 East Riding of Yorkshire (UA) 16 Kingston upon Hull, City of (UA) 41 North East Lincolnshire (UA) 41 North Lincolnshire (UA) 42 North Yorkshire 44 South Yorkshire 106 West Yorkshire 117 York (UA) 130 The Heritage at Risk Register helps us to identify the most threatened buildings, archaeological sites and landscapes in this most distinctive of English regions. For the 60% of listed buildings on this year’s Register that could have a sustainable future through commercial or residential reuse, the economic downturn has brought additional challenges to which we must now respond. This year, we undertook a pioneering 15% sample survey of England’s 14,500 listed places of worship to help us understand the condition of the thousands of designated churches, chapels, synagogues, mosques and temples and other faith buildings that are the spiritual focus for our communities. They face many different kinds of challenges and we need to ensure their future. In response to the expansion of asset types and changed Last year we included conservation areas in the Register economic conditions we have developed a new strategy. for the first time. This year, 46 of these, including Haworth, From now on we will focus our resources on types of Holbeck and Rotherham, are known to be at risk, site that make a particular contribution to the region’s but the survey of nearly 800 areas is proving a challenging character. -

(Designated Rural Areas in the North East) Order 1997

Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 1997 No. 624 HOUSING, ENGLAND AND WALES The Housing (Right to Acquire or Enfranchise) (Designated Rural Areas in the North East) Order 1997 Made - - - - 5th March 1997 Laid before Parliament 7th March 1997 Coming into force - - 1st April 1997 The Secretary of State for the Environment, as respects England, in exercise of the powers conferred upon him by section 17 of the Housing Act 1996(1) and section 1AA(3)(a) of the Leasehold Reform Act 1967(2) and of all other powers enabling him in that behalf, hereby makes the following Order— Citation and commencement 1. This Order may be cited as the Housing (Right to Acquire or Enfranchise) (Designated Rural Areas in the North East) Order 1997 and shall come into force on 1st April 1997. Designated rural areas 2. The following areas shall be designated rural areas for the purposes of section 17 of the Housing Act 1996 (the right to acquire) and section 1AA(3)(a) of the Leasehold Reform Act 1967 (additional right to enfranchise)— (a) the parishes in the districts of the East Riding of Yorkshire, Hartlepool, Middlesborough, North East Lincolnshire, North Lincolnshire, Redcar and Cleveland and Stockton-on-Tees specified in Parts I, II, III, IV, V, VI and VII of Schedule 1 to this Order and in the counties of Durham, Northumberland, North Yorkshire, South Yorkshire, Tyne and Wear and West Yorkshire specified in Parts VIII, IX, X, XI, -

Where the Council Tax Goes (2020/21)

Council Tax 7/3/19 09:19 Page 1 WHERE YOUR COUNCIL TAX GOES In 2020/21 people who live in the Scarborough Borough will pay £75.957 million in Council Tax, including Town and Parish Precepts. This money will go to the following: Scarborough Borough Council £9.26m (2.13% increase) Town and Parish Precepts £0.96m (6.79% increase) North Yorkshire County Council £48.04m (1.99% increase) North Yorkshire County Council Adult Social Care £4.63m (2.00% increase) The Police & Crime Commissioner for North Yorkshire £10.27m (3.91% increase) North Yorkshire Fire & Rescue Service £2.81m (1.99% increase) These authorities will also get money from the Government and from Fees and Charges to pay for the services they provide. The Borough Council collects the money on behalf of all the authorities and the total per Band is shown in the table below. THE POLICE & CRIME SCARBOROUGH NORTH YORKSHIRE NYCC ADULT NORTH YORKSHIRE BAND COMMISSIONER FOR TOTAL BOROUGH COUNCIL COUNTY COUNCIL SOCIAL CARE FIRE & RESCUE NORTH YORKSHIRE A £159.83 £829.07 £79.91 £177.18 £48.46 £1,294.45 B £186.47 £967.25 £93.22 £206.71 £56.54 £1,510.19 C £213.11 £1,105.43 £106.54 £236.24 £64.61 £1,725.93 D £239.75 £1,243.61 £119.86 £265.77 £72.69 £1,941.68 E £293.03 £1,519.97 £146.50 £324.83 £88.84 £2,373.17 F £346.31 £1,796.33 £173.13 £383.89 £105.00 £2,804.66 G £399.58 £2,072.68 £199.77 £442.95 £121.15 £3,236.13 H £479.50 £2,487.22 £239.72 £531.54 £145.38 £3,883.36 If you have a Parish or Town Council in your area your final bill will also include a contribution to them. -

David Duggleby Auctioneers & Valuers

David Duggleby Auctioneers & Valuers Antiques, Interiors, Jewellery & Garden The Vine Street Salerooms Vine Street Scarborough Antiques, Ceramics, Jewellery, Clocks, Gold, Silver, Cabinet North Yorkshire Lots, Pictures + Antique, Retro & Reproduction Furniture, YO11 1XN Garden Lots United Kingdom Started 23 Jul 2016 10:00 BST Lot Description Macintyre 'Alhambra' vase designed by William Moorcroft c.1904 H13.5cm Condition Report Very good conditionClick here for further 1 images, condition, auction times & delivery costs William Moorcroft Florian Ware 'Peacock' vase c.1900 H16cm Condition Report Click here for further images, condition, auction times & 2 delivery costs William Moorcroft MacIntyre jar and cover c. 1900 D. 13cm Condition Report Click here for further images, condition, auction times & 3 delivery costs William Moorcroft MacIntyre three piece tea set decorated with a border pattern from the 404017 design, c.1903, Rd. No. 311909 4 Condition Report Click here for further images, condition, auction times & delivery costs William Moorcroft 'Poppy' twin handled footed bowl c. 1920 D.21cm Condition Report Click here for further images, condition, auction 5 times & delivery costs Walter Moorcroft 'Hibiscus' Flambe vase c.1940s H26cm Condition Report Click here for further images, condition, auction times & 6 delivery costs 7 Moorcroft 'Glendair' vase H35cm, boxed Condition Report Click here for further images, condition, auction times & delivery costs Moorcroft 'Bergamot' limited edition vase no. 71/100 H32cm, boxed Condition Report Very good condition: no cracks, chips or 8 restoration. First quality.Click here for further images, condition, auction times & delivery costs Moorcroft 'Woodland Waxwing' limited edition vase, no 82/100 H30cm, boxed Condition Report Very good - no chips, cracks or 9 restoration. -

Identify Your Favourite Businesses from the List

STEP 1: Identify your favourite businesses from the list - they are sorted by Postcode/Street Business Directory - All Businesses in Newark v3.xlsx STEP 2: Log into weeconomy.com and check to see if it's already on the map STEP 3: If it's not shown, ADD it now before someone else does! Company Address Business Type Business Location Nationals Postcode Lincoln Volkswagen Specialists Aqua House/Newark Rd, Lincoln LN5 9EJ Car Dealer - Newark LN5 9EJ Vital2 Ltd Lincoln Enterprise Park, Newark Rd, Aubourn, Lincoln LN5 9EJ Gym - Newark LN5 9EJ HeadOffice Hair Salon 310 Newark Rd, North Hykeham, Lincoln LN6 8JX Beauty Salon - Newark LN6 8JX SJ Bean Longcase clock dial restorationNewark and Rd, clock Lincoln repairs LN6 8RB Antique - Newark LN6 8RB Best Western Bentley Hotel And SpaNewark Rd, South Hykeham, Lincoln LN6 9NH Dry Cleaners - Newark LN6 9NH M H Motors Staunton Works/Unit 1 Newark Rd, Nottingham NG13 9PF MOT - Newark NG13 9PF The Angel Inn Main Street, Kneesall, Newark, Nottinghamshire NG22 0AD Bar - Newark NG22 0AD Howes R J Kirklington Road, Newark NG22 0DA Bed and Breakfast - Newark NG22 0DA The Saville Arms Saville Arms/Bilsthorpe Rd, Newark NG22 0DG Bar - Newark NG22 0DG Thoresby Aesthetica Back Lane, Newark, Nottinghamshire NG22 0DJ Beauty Salon - Newark NG22 0DJ Olde Red Lion Eakring Road, Newark, Nottinghamshire NG22 0EG Bar - Newark NG22 0EG The Old Plough Inn Main Street, Newark, Nottinghamshire NG22 0EZ Public House - Newark NG22 0EZ The Fountain Tuxford 155 Lincoln Road, Tuxford, Newark NG22 0JQ Bar - Newark NG22 0JQ Sally