Nekrasov Cossacks' Festive Clothes: Historical Changes and Modern Functions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dear Colleagues! 20.05 21.05 22.05 Sfedu.Ru Confecon.Sfedu.Ru

Dear Colleagues! The Southern Federal University is glad to invite you to take part in the Conference MULTIPOLAR GLOBALIZATION AND RUSSIA to be held on May 20-22, 2021. The Conference is focused on topical problems of modern economy, theory and practice of modernization, and trends in economic development in Russia and the world. The conference will be held in the form of plenary session, group sessions, and roundtables in the sphere of: Conference schedule − international economic cooperation: competition, - Plenary Session of the integration, corporations; 20.05 Conference - Group Sessions Rostov-on-Don, − economic, social and legal aspects of doing B. Sadovaya St., 105/42, Main building of SFedU international business facing new challenges; − the philosophy of management system in - Group Sessions and understanding global changes; 21.05 roundtables; - Sightseeing tour of Taganrog − entrepreneurship in a global environment: Taganrog, Nekrasovsky lane, 44, education, research, business practice; Educational building "D" - Closing meeting of the − m anagement of socio-economic development in 22.05 Conference; the context of global transformations; - Sightseeing tour of Starocherkasskaya − service and tourism in the development of the modern world. Conference - Russian languages - English Form of - on site * participation - online The conference will be held taking into account all necessary sanitary standards. sfedu.ru * In case of deteriorating epidemiological situation, the Conference will be held online. confecon.sfedu.ru REGISTRATION AND Programme committee SUBMISSIONS Shevchenko I.K. – Doctor of Economics, Professor, Rector of the Southern Federal University (Chairman of the Program Committee); Metelitsa A.V. – Doctor of Chemical Sciences, Professor, Vice-Rector for Scientific and To participate in the Conference, you Research Activities of the Southern Federal University (Deputy Chairman of the Program Committee); should fill out the registration form by Afontsev S.A. -

Donna Arnold, University of North Texas Serge Jaroff's Don Cossack Choir Was Founded at a Miserable Turkish Concentration Camp

Serge Jaroff and the Don Cossack Choir: the State of Research in the 21st Century Donna Arnold, University of North Texas Serge Jaroff’s Don Cossack Choir was founded at a miserable Turkish concentration camp in 1921 in an attempt to raise morale. It drew singers from the Tsarist Don Cossack regiments deported by the Red Army after their defeat in the Russian revolution. Jaroff, a detainee, had graduated from the famous Moscow Synodal Choir School, so he was ordered to conduct it. He arranged repertoire for it from memory, and against all odds, polished 36 amateurs into a brilliant world-class unit. Once freed, the destitute men stayed together and kept singing. Discovered by an impresario, they gave a groundbreaking concert at Vienna’s Hofburg on July 4, 1923, which launched their remarkable professional career. They proceeded to tour the world with unimaginable A very early picture of the choir A very young success for nearly 60 years. They always sang only in Russian, and they always wore the same kind of austere Serge Jaroff Cossack uniforms they had been wearing when they were deported. For 22 years Jaroff and his choristers travelled with “Nansen” passports, devised by the League of Nations for Russian émigrés without a country. The passports read “en voyage” where a country name would have been. For some time the men were based in Germany, but they sought Fast Forward: permanent-resident status in the United States as war was breaking out The choir gave its last concert in Paris in 1979; Serge Jaroff died in New Jersey in 1985. -

Urban Representation in Fashion Magazines

Chair of Urban Studies and Social Research Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism Bauhaus-University Weimar Fashion in the City and The City in Fashion: Urban Representation in Fashion Magazines Doctoral dissertation presented in fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor philosophiae (Dr. phil.) Maria Skivko 10.03.1986 Supervising committee: First Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Frank Eckardt, Bauhaus-University, Weimar Second Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Stephan Sonnenburg, Karlshochschule International University, Karlsruhe Thesis Defence: 22.01.2018 Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 5 Thesis Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 6 Part I. Conceptual Approach for Studying Fashion and City: Theoretical Framework ........................ 16 Chapter 1. Fashion in the city ................................................................................................................ 16 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 16 1.1. Fashion concepts in the perspective ........................................................................................... 18 1.1.1. Imitation and differentiation ................................................................................................ 18 1.1.2. Identity -

Fine Art, Antiques, Jewellery, Gold & Silver, Porcelain and Quality

Fine Art, Antiques, Jewellery, Gold & Silver, Porcelain and Quality Collectables Day 1 Thursday 12 April 2012 10:00 Gerrards Auctioneers & Valuers St Georges Road St Annes on Sea Lancashire FY8 2AE Gerrards Auctioneers & Valuers (Fine Art, Antiques, Jewellery, Gold & Silver, Porcelain and Quality Collectables Day 1 ) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 Lot: 14 A Russian Silver And Cloisonne 9ct Gold Diamond & Iolite Cluster Enamel Salt. Unusual angled Ring, Fully Hallmarked, Ring Size shape. Finely enamelled in two T. tone blue, green red & white and Estimate: £80.00 - £90.00 with silver gilt interior. Moscow 84 Kokoshnik mark. (1908-1917). Maker probably Henrik Blootenkleper. Also French import mark. Estimate: £100.00 - £150.00 Lot: 15 9ct White Gold Diamond Tennis Lot: 2D Bracelet, Set With Three Rows A Russian 14ct Gold Eastern Of Round Cut Diamonds, Fully Shaped Pendant Cross. 56 mark Hallmarked. & Assay Master RK (in cyrillic). Estimate: £350.00 - £400.00 Maker P.B. Circa 1900. 2" in length. 4 grams. Estimate: £80.00 - £120.00 Lot: 16 9ct Gold Opal And Diamond Stud Lot: 8D Earrings. Pear Shaped Opal With Three Elegant Venetian Glass Diamond Chips. Vases Overlaid In Silver With Estimate: £35.00 - £45.00 Scenes Of Gondolas And Floral Designs. Two in taupe colour and a larger one in green. Estimate: £30.00 - £40.00 Lot: 17 Simulated Pearl Necklace, White Lot: 10 Metal Clasp. Platinum Diamond Stud Earrings, Estimate: £25.00 - £30.00 Cushion Shaped Mounts Set With Princess Cut Diamonds, Fully Hallmarked, As New Condition. Estimate: £350.00 - £400.00 Lot: 18 9ct Gold Sapphire Ring, The Lot: 12 Central Oval Sapphire Between Large 18ct Gold Diamond Cross, Diamond Set Shoulders, Ring Mounted With 41 Round Modern Size M, Unmarked Tests 9ct. -

Andreas Kappeler. Die Kosaken: Geschichte Und Legenden

Book Reviews 181 Andreas Kappeler. Die Kosaken: Geschichte und Legenden. Munich: Verlag C. H. Beck, 2013. 127 pp. 20 illustrations. 2 maps. Index. Paper. ndreas Kappeler has done it again! Over twenty years ago, he published A a brief history of Ukraine, in which he managed to pack the most important parts of the history of the country into a mere 286 pages. Not only was that work brief and to the point, but it also held to a relatively high level of scholarship and made a number of interesting and well-grounded generalizations. In that book, Kappeler anticipated the longer and more detailed work of Paul Magocsi by experimenting with a multinational and polyethnic history of the country. In the present work, Kappeler is equally brief and to the point and has again produced a well-thought-out and serious history, this time of the Cossacks, and he has again included some important generalizations. Although in this volume, the multinational and polyethnic elements are not quite so prominent, he does make note of them, and, in particular, he compares the Ukrainian and Russian Cossacks on several different levels. Kappeler begins with geographic and geopolitical factors and notes that both the Ukrainian and Russian Cossacks originated along rivers—the Dnieper and the Don, respectively—as defenders of the local Slavic population against the Tatars and the Turks. He describes the successful Ukrainian Cossack revolt against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and what he calls “the Golden Age of the Dnieper Cossacks” under their leaders, or hetmans, Bohdan Khmel'nyts'kyi and Ivan Mazepa; and then the eventual absorption of their polity, the Ukrainian Cossack Hetmanate, into the Russian Empire. -

Ilya Repin and the Zaporozhe Cossacks

Skidmore College Creative Matter MALS Final Projects, 1995-2019 MALS 5-17-2008 Ilya Repin and the Zaporozhe Cossacks Kristina Pavlov-Leiching Skidmore College Follow this and additional works at: https://creativematter.skidmore.edu/mals_stu_schol Part of the European History Commons, and the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Pavlov-Leiching, Kristina, "Ilya Repin and the Zaporozhe Cossacks" (2008). MALS Final Projects, 1995-2019. 50. https://creativematter.skidmore.edu/mals_stu_schol/50 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the MALS at Creative Matter. It has been accepted for inclusion in MALS Final Projects, 1995-2019 by an authorized administrator of Creative Matter. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ilya Repin and the Zaporozhe Cossacks by Kristina Pavlov-Leiching FINAL PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN LIBERAL STUDIES SKIDMORE COLLEGE May 2008 Advisors: Kate Graney, Ken Klotz THE MASTER OF ARTS PROGRAM IN LIBERAL STUDIES SKIDMORE COLLEGE CONTENTS ABSTRACT . .. .. iv LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . v Chapter INTRODUCTION . .. .. .. 1. Goals of the Study 1. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND . .. .. .. 3. Repin and the Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg Repin's Experiences Abroad Repin and the Wanderers Association Repin as a Teacher and Reformer Repin's Final Years 2. REPIN'S AESTHETIC BELIEFS AS AN ARTIST AND TEACHER . .................................. 15. An Artist Driven by Social Obligation A Painter of the Peasantry and Revolutionary A Devout Nationalist An Advocate of Art forAr t's Sake(1873-1876 & 1890s) Impressionist Influence An Encounter with Tolstoy's Aesthetics Repin as a Teacher and Reformer of the Academy The Importance of the Creative Process A Return to National Realism 11 3. -

Military Traditions of the Don Cossacks in the Late Imperial Period T

Вестник СПбГУ. История. 2020. Т. 65. Вып. 3 Military Traditions of the Don Cossacks in the Late Imperial Period T. E. Zulfugarzade, A. Yu. Peretyatko For citation: Zulfugarzade T. E., Peretyatko A. Yu. Military Traditions of the Don Cossacks in the Late Imperial Period. Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University. History, 2020, vol. 65, issue 3, рp. 771–789. https://doi.org/10.21638/11701/spbu02.2020.305 The issue of the development of military traditions in the Cossack milieu on the eve of the 20th century is a matter of debate in contemporary Russian historiography. A number of scholars (e. g., A. V. Iarovoi and N. V. Ryzhkova) have argued that the Cossacks’ system of historical military traditions remained viable until 1917. Other researchers (e. g., O. V. Matveev) have claimed that the system of Cossack military traditions had actually experienced a crisis and collapsed by then. This paper seeks to establish the truth. To accomplish this, the authors draws upon a set of newly discovered responses from Russian generals to the report of the Maslakovets Commission. The paper shows that the Cossacks’ historical traditions of military training in the stanitsas were forgotten not by the beginning of the 20th century, but by the 1860s. During this time, declining combat capability of the Don units, with 50 % of the young Cossacks entering military service by the beginning of the 20th century “poorly” and “unsat- isfactorily” prepared, drew the attention of Alexander II. The War Ministry endeavored to revive the Cossacks’ martial games and military training in the stanitsas. However, according to certain Cossack generals, its actions, at the same time, had violated the historical Cossack traditions of military training, causing, by certain testimonies, their total ruin by the begin- ning of the 20th century. -

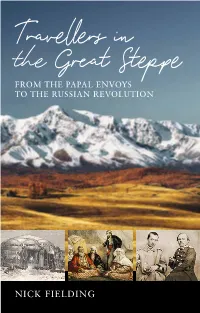

Nick Fielding

Travellers in the Great Steppe FROM THE PAPAL ENVOYS TO THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION NICK FIELDING “In writing this book I have tried to explain some of the historical events that have affected those living in the Great Steppe – not an easy task, as there is little study of this subject in the English language. And the disputes between the Russians and their neighbours and between the Bashkirs, the Kazakhs, the Turkomans, the Kyrgyz and the Kalmyks – not to mention the Djungars, the Dungans, the Nogai, the Mongols, the Uighurs and countless others – means that this is not a subject for the faint-hearted. Nonetheless, I hope that the writings referred to in this book have been put into the right historical context. The reasons why outsiders travelled to the Great Steppe varied over time and in themselves provide a different kind of history. Some of these travellers, particularly the women, have been forgotten by modern readers. Hopefully this book will stimulate you the reader to track down some of the long- forgotten classics mentioned within. Personally, I do not think the steppe culture described so vividly by travellers in these pages will ever fully disappear. The steppe is truly vast and can swallow whole cities with ease. Landscape has a close relationship with culture – and the former usually dominates the latter. Whatever happens, it will be many years before the Great Steppe finally gives up all its secrets. This book aims to provide just a glimpse of some of them.” From the author’s introduction. TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE For my fair Rosamund TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE From the Papal Envoys to the Russian Revolution NICK FIELDING SIGNAL BOOKS . -

Russian Place-Names of 'Hidden' Or 'Indirect' Scottish Origin

Russian place-names of ‘hidden’ or ‘indirect’ Scottish origin (the case of Hamilton – Khomutov) Alexander Pavlenko and Galina Pavlenko In Russia there are numerous toponyms going back to personal or place names of western European origins. This phenomenon resulted from several waves of massive immigration from the West, first to Muscovite Rus’ and later, in greater numbers, to the Russian Empire. Among the immigrants, most of whom originated from Germany, there was quite a number of Scotsmen – active participants in all the major historical events in both Western and Eastern Europe. The first Scotsmen in Russia, called Shkotskie Nemtsy (literally ‘Scottish Germans’) by locals, belonged to the military class and came to this country either as mercenaries or prisoners of war in the late sixteenth century in the reign of Ivan the Terrible. Most of them were captured during the Livonian War and continued their military service in the Russian troops (Anderson 1990: 37). In the seventeenth century with the accession of the Romanovs dynasty to the throne, Scotsmen started to arrive in Russia in ever increasing numbers. Some of those who abandoned their motherland, driven by circumstances managed to inscribe their names in Russian history as prominent soldiers, engineers, doctors, architects, etc. Scottish mercenaries and adventurers considered the remote Russian lands to be a place where they could build their career and hopefully make a fortune. Of course, as is well known, Russia was only one of a multitude of destinations which Scotsmen sought to reach. The late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries saw a more abundant influx of Scots due to the Petrine reforms and a high demand for foreign professionals in all fields (Dukes 1987: 9–23; Cross 1987: 24–46). -

SPECIAL ANNUAL YEARBOOK EDITION Featuring Bilateral Highlights of 27 Countries Including M FABRICS M FASHIONS M NATIONAL DRESS

Published by Issue 57 December 2019 www.indiplomacy.com SPECIAL ANNUAL YEARBOOK EDITION Featuring Bilateral Highlights of 27 Countries including m FABRICS m FASHIONS m NATIONAL DRESS PLUS: SPECIAL COUNTRY SUPPLEMENT Historic Singapore President’s First State Visit to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia CONTENTS www.indiplomacy.com PUBLISHER’S NOTE Ringing in 2020 on a Positive Note 2 PUBLISHER Sun Media Pte Ltd EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Nomita Dhar YEARBOOK SECTION EDITORIAL Ranee Sahaney, Syed Jaafar Alkaff, Nishka Rao Participating foreign missions share their highlights DESIGN & LAYOUT Syed Jaafar Alkaff, Dilip Kumar, of the year and what their countries are famous for 4 - 56 Roshen Singh PHOTO CONTRIBUTOR Michael Ozaki ADVERTISING & MARKETING Swati Singh PRINTING Times Printers Print Pte Ltd SPECIAL COUNTRY SUPPLEMENT A note about Page 46 PHOTO SOURCES & CONTRIBUTORS Sun Media would like to thank - Ministry of Communications & Information, Singapore. Singapore President’s - Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Singapore. - All the foreign missions for use of their photos. Where ever possible we have tried to credit usage Historic First State Visit and individual photographers. to Saudi Arabia PUBLISHING OFFICE Sun Media Pte Ltd, 20 Kramat Lane #01-02 United House, Singapore 228773 Tel: (65) 6735 2972 / 6735 1907 / 6735 2986 Fax: (65) 6735 3114 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.indiplomacy.com MICA (P) 071/08/2019 © Copyright 2020 by Sun Media Pte Ltd. The opinions, pronouncements or views expressed or implied in this publication are those of contributors or authors. They do not necessarily reflect the official stance of the Indonesian authorities nor their agents and representatives. -

Donntu's Delegation Participates in the Forum “The Russian World

Donetsk National Technical University ʋ10 INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION (223) Newsletter 2018 DonNTU’s Delegation Participates in the Forum “The Russian World and Donbass: from Collaboration to Integration” The representatives of Donetsk National Technical University – the Rector Prof. Marenich, the Vice-Rector Prof. Navka, the Dean of the Engineering and Economic Faculty Dr. Zhilchenkova, the Head of the Department of Economic Theory and State Administration Dr. Vishnevskaya – participated in the plenary meeting of the International Integration Forum “The Russian World and Donbass: from Collaboration to Integration” which took place at the conference hall of hotel-and-restaurant complex “Shakhtar Plaza” on October 23d . The caretaker of the Head of the Government of the DPR Mr. D Pushilin, the caretaker of the Head of the Government of the LPR Mr. L. Pasechnik, the RF State Duma deputy, the coordinator of the integration committee “Russia-Donbass” Mr. A. Kozenko, and public figures, workers of the sphere of education, science and culture from different countries participated in it. The forum was held on October 23-26th. Round table meetings, conferences in Donbass integration into the educational, cultural and economic space of the Russian Federation were organized in the frameworks of the event. DonNTU’s New International Agreement On October 10th DonNTU signed an agreement on collaboration and double degrees with South-Ural State University. It is aimed at developing scientific and technical interaction, widening of creative links, assisting in international educational process and integrating into the world system of university education. Prof. K. Marenich and Dr. I. Kondaurova, the Head of the Department of Business and Staff Administration, were present at the ceremony of its signing. -

5 Types of Kokoshnik Tiaras

5 TYPES OF KOKOSHNIK TIARAS There’s a surprising variety of design possibilities for kokoshnik tiaras. Here are 5 drool-worthy examples and their stories. FILE UNDER: TIARAS WANT ME TO READ THIS POST TO YOU? N A PREVIOUS POST, I TALKED ABOUT I Grand Duchess Hilda of Baden’s stolen tiara. That tiara is a kokoshnik, so I thought I’d explain what that means and show you a few examples. WHAT’S A KOKOSHNIK? THE KOKOSHNIK IS A TRADITIONAL Russian headdress. It’s shaped like a halo, widest above the forehead and a little narrower at the sides. If you’ve seen the golden halos of saints in Russian icons or other Christian art, you get the general idea. Here’s a Russian icon of Our Lady of Kazan from the 19th century: IMAGE B Y ХОМЕЛКА, CC BY- SA 3.0 VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS. GIRLINTHETIARA.COM | 5 TYPES OF KOKOSHNIK TIARAS The earliest versions of kokoshniks were covered with fabric and tied on with ribbons at the side. This version is from a painting by Viktor Vasnetsov – he was famous for his romanticized depictions of Russian history and folklore, including a super-famous painting of Ivan the Terrible you’d probably recognize if you saw it. You know the one – Ivan’s throwing creeptastic side-eye, dressed in a fur cap and gold brocade tunic, and holding a staff with a pointy end like he’s about to stab a bitch. IMAGE BY ВАСНЕЦОВ, P UBLIC DOMAIN VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS. GIRLINTHETIARA.COM | 5 TYPES OF KOKOSHNIK TIARAS The kokoshnik was part of traditional Russian folk dress, along with the sarafan – a sort of jumper or pinafore with a blouse underneath.