Resuscitation Onboard Rescue Boats

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FCN April11 Finalb

Formby Civic News The Formby Civic Society Newsletter Registered Charity no 516789 April 2011 Listed Cottage in Peril by Desmond Brennan Inside this issue: Listed Cottage 2 in Peril. Planning 3 Matters. Managing 4 Woodland. Dr Sumner & 3 the Lifeboat. Wildlife Notes. 8 History Group 10 Eccle’s Cottage , Southport Road, 1968; photo M. Sibley. Report. 11 The cottage at 1 Southport Road, known “Outbuildings and Croft”. Reg Yorke Art Group Re- until modern times as Eccles Cottage or suspects the Paradise Lane buildings port. Eccles Farm, is located on the north side were a good deal older than the sole sur- Ravenmeols 12 of the road at its junction with Paradise vivor of this group of buildings. James Heritage Trail. Lane. It dates from the first half of the Eccles paid 7d Tithe to the Rector for his 18th century and is a Grade 2 Listed house and 4d for the “outbuildings”. Formby-by-the 12 Building. The 1968 photograph of the -Sea. After several years of neglect, today building shows at that time it was in rea- Chairman’s 15 finds the building in a parlous state, es- sonable condition, although, even then, Notes the unevenness of the roof indicates that pecially the single story with attic part of all was not well with its timbers. The New Notelets. 15 detail from the 1845 Tithe map (see next page) shows that, in its early days, the cottage was surrounded by an extensive NEW NOTELETS patchwork of fields - very different from today. We know from the information (See page 16) accompanying the map that, at that time, the property was owned by Mary Form- Now available from by and occupied by James Eccles, who Select, Derbyshires, also “occupied” the somewhat longer Ray Derricott or neighbouring cottage further along Para- Tony Bonney dise Lane which he used as Listed Cottage in Peril After several years of neglect, today the building which is believed to be cantly impaired as a result of the tional circumstances may harm to or older than the 2-storey eastern end. -

Lesson Plan – 5.2-1 Plan Search and Rescue AIM

Date: 12/1/18 Lesson Plan – 5.2-1 Plan Search and Rescue Mark Harker Cowes LTA / Helm AIM: Trainer - Explain the information required to plan a Sar, additional information to be sought ;factors of how to decide on the appropriate type of SAR plan / plan; elements affecting the success of SAR. Crew - to have a broad basic understanding of the factors involved in SAR, how it's planned and the considerations. Training Shoreside – ● Explanation of the information required and advantageous ● The type of SAR patterns and methods ● Factors affecting the success of a SAR ● How to calculate the DSP and CSP ● How to plot on a paper chart and SIMs CSP and casualty position ● Use of SAR cards ● Crew briefings and crew roles ● Crew should be able to plot the DSP and calculate the CSP on either a paper chart or SIMs unit. Training afloat - Demonstrate planning SAR pattern and execution; the communication and factors. RNLI Training - crew course Initial Information The vital pieces of information required by the lifeboat to execute a shout are 1) The nature of the incident 2)Where to search or (CSP - Commence Search Position) 3)search Target. Additional information the help the search be more effective, successful and quicker may include ● Type of vessel / details about the person ● Tides, weather, wind ● Number of persons ● Other vessels or assets involved ● Incident coordinator ● Source of information such as first informant ● where and when were they last seen (position and time) ● What was the reason for the alert call Information that will assist in the success of a SAR can come from a variety of sources: ● The person reporting the incident (999 or VHF call), they may also continue to provide information through the incident. -

Of the of the Rnli

1790 1824 1838 1861 HISTORY Henry Greathead invents Grace Darling lives in a lighthouse on the Original – the first ever the rocky Farne Islands with her father. OF THE lifeboat. She saves lives in She becomes a national heroine when South Shields for 40 years. she risks her life to rescue survivors FACT: William Hillary of a shipwreck in stormy seas. RNLI Before steam, the first lifeboats LEARN: RNLI.org/GraceDarling only had oars to power them, so starts the charity at a the crew had to be really strong! time when there are 1939–45 a whopping 1,800 FACT: shipwrecks every year A lifeboat capsizes in Whitby, Yorkshire, 1935 In the beginning, the RNLI around our coasts. killing 12 crew members! Only one man, was called The National Henry Freeman, survives. He was TIP: Institution for the Preservation of Life from Shipwreck the only one wearing a lifejacket. Always wear a lifejacket! During the Second World War, lifeboats save 6,376 lives. And, 1905 in a rescue mission to 1914–18 France with a fleet of The last time a lifeboat 1907 700 small boats, two is launched by horses. RNLI lifeboat crews save Horses were replaced with 3,400 soldiers from the caterpillar tractors. beaches of Dunkirk. FACT: We still use special tractors today to LEARN: RNLI.org/WW2 1947 launch our Shannon class lifeboats The first motor lifeboats are tested. They are less heavy than steam lifeboats, more powerful and easier to control. 1972 During the First World War, lifeboats Major rescue! 456 people are launch 1,808 times and save 5,332 lives. -

RNLI Factsheet on Trent Class

Lifesaving in action Clark Russell Photo: In 2008, Trent class lifeboats launched 614 times and rescued 791 people. In total, RNLI lifeboats launched 8,293 times, rescuing 7,612 people – an average of 21 people a day. Making a difference Just after midnight on 2 July 2007 Alderney’s Kevin, a diabetic who hadn’t had a chance Trent class lifeboat crew launched to one of to eat, remembered: ‘I was on the verge of their most challenging rescues to date. collapse but adrenaline kicked in. It was like Kevin Payne, his friend and his dog were on being on a rollercoaster – down and up and a dream voyage aboard his lovingly converted down and up. But on this rollercoaster you had trawler when, in gale force winds and 4m to stand up and move around.’ waves, she started rapidly taking on water. With Several attempts, near misses and feats of the generator swamped, they had no electric skill and perseverance later, the four men and pump, main VHF radio or lights. a dog were on their way back in the lifeboat. As The trawler was heavy and rolling far too Kevin passed in and out of consciousness, his violently for the lifeboat crew to consider trawler sank with everything he owned onboard. towing. After some tricky manoeuvring, two He later made a full recovery. crew managed to get aboard. Over the next 30 Crew Member Mark Gaudion said: ‘The minutes they did everything they could but it boats they give us to do the job are second to became increasingly dangerous. -

Early Lifeboat Stations

Source 3: Early lifeboat stations One of the earliest pieces of evidence proving the existence of of Persons Apparently Drowned), this organisation aimed to retrieve a boat kept on the coast at Formby for the sole purpose of saving and resuscitate victims of drowning with specially trained medical lives at sea is an extract from the Liverpool Common Council assistants and also provided payments to bystanders who rescued meeting on 2 April 1777. them. William Hutchinson, the Liverpool Dock Master and Water Although the boat was not at that time called a ‘lifeboat’, Formby Bailiff (1759–93), was another man influencing Liverpool’s humane was, nevertheless, credited as being one of the first lifeboat stations. movement. His text, A Treatise on Practical Seamanship (1777), The extract shows how Liverpool Town Council funded an organised promoted safe navigation and rescues to ships in distress. system of rescue from shipwreck at the mouth of the River Mersey. Such schemes and books intended to confront the British public As the second busiest port in Britain at the time, Liverpool was with the inhumanity of leaving others to die at sea. pioneering in the area of lifesaving at sea. For example, Dr Thomas It is thought that Sir William Hillary, who campaigned to set up Houlston set up the Liverpool Institution for Recovering Drowned the National Institution for the Preservation of Life from Shipwreck Persons in 1775. Like the Royal Humane Society based in London (now the RNLI), would have been aware of these Liverpool schemes (established in 1774 and then called the Society for the Recovery for lifesaving at sea. -

Rnli Operational Statistics

RNLI OPERATIONAL STATISTICS REPORT 2019 This photo: June 1983 – The RNLI’s first Tyne class lifeboat City of London 47-001 on trials at Selsey Front cover photo: April 2019 – The last of the Tyne class lifeboats Annie Blaker 47-035 with her devoted Wicklow crew 2 FAREWELL TO THE TYNE On Sunday 28 April 2019 at 1.30pm, the last of our Tyne class all-weather lifeboats made her final launch. Annie Blaker (shown on the front cover) 1982–2019 YEARS37 OF THE TYNE devoted 30 years to saving lives at sea at XXXXXX XXXX Wicklow and was very much part of 47-000 40 the team. TYNE CLASS ‘She has been as much a part of the crew LIFEBOATS as any volunteer that passed through our TYNE FACTS BUILT doors and she has earned her retirement,’ ‘ Her personality? First Tyne says Des Davitt, Lifeboat Operations Manager ON1074 (47-001) City of London for Wicklow RNLI. Rock solid’ Built 1982 With a top speed of 18 knots, the Tyne CONNIE O’GARA Selsey Lifeboat Station 14,009 was twice as fast as the motor lifeboats she CREW MEMBER AND DEPUTY 1983–2006 LAUNCHES was designed to replace, revolutionising MECHANIC, WICKLOW LIFEBOAT lifesaving at sea. She was introduced to the Last Tyne fleet in 1982 and was the RNLI’s first fast ON1153 (47-035) Annie Blaker slipway lifeboat. Built 1989 2,615 LIVES ‘ A reliable big sister, Wicklow Lifeboat Station 1989–2019 SAVED ‘A HUGE LEAP’ always there waiting Speaking about the first time he stepped to help’ • The Tyne was the first fast onboard the Tyne, Ciarán Doyle, Second slipway boat (FSB1). -

We Are the Rnli the Charity That Saves Lives At

FACTSHEET May 2018 Every day of the year, people get into trouble WE ARE in the water. Our lifeboat crews provide a 24-hour rescue service in the UK and Ireland. Every summer, THE RNLI our lifeguards look after people on busy beaches. And our Flood Rescue Team is ready to help those THE CHARITY affected by flooding. Our community safety teams and education THAT SAVES volunteers help explain the risks and share safety knowledge with anyone at risk of drowning. LIVES AT SEA Our international teams work with partners to help tackle drowning in communities at risk all around the world. And thousands of RNLI volunteer fundraisers help to support our lifesaving work. Photos: RNLI/(Rob McDougall, Nigel Millard, Nathan Williams, Jon Stokes) OUR OUR RESCUE MAP OUR LIFEBOAT FLOOD RESCUE CREW TEAM RNLI lifeboat crew members come TRAINING from different backgrounds and careers Today, only 1 in 10 of our volunteer crew members comes from a maritime profession, so training is essential. They don't just need – from teachers to tattooists, farmers to boathandling skills – they learn everything from navigation and engine pharmacists. At a moment’s notice, they repair to first aid and sea survival. Our training provides crew members readily exchange work, comfort and sleep with comprehensive courses and recognised qualifications. These high standards are maintained and developed with the help of the for cold, wet and fatigue. training staff and facilities at the RNLI College in Poole, Dorset, which complements training around the coast. This central facility provides They spend many hours of their own time accommodation, classrooms and distance-learning resources. -

Arun Barnett 52Ft Barnett 60Ft Brede Barnett 51Ft Clyde

Arun Brede Clyde Photo credit: RNLI Photo credit: RNLI Photo credit: RNLI Photo credit: LENGTH (m): 15.8 Serving from 1971 LENGTH (m): 10 LENGTH (m): 21.3 WEIGHT (t): 32 to 2008, the Arun class WEIGHT (t): 8.5 When introduced in 1982, WEIGHT (t): 78 The Clyde class lifeboat lifeboat vastly improved the Brede class was was the largest ever built TOP SPEED (kn): 18.5 TOP SPEED (kn): 18.6 TOP SPEED (kn): 11.5 the accommodation the fastest lifeboat in for the RNLI and the first RANGE (nm): 250 and speed capabilities RANGE (nm): 140 our fleet. RANGE (nm): 1700 to have a steel hull. DATE FIRST LAUNCHED: 1971 of the fleet at the time. DATE FIRST LAUNCHED: 1982 DATE FIRST LAUNCHED: 1968 SERVICE LENGTH (yrs): 37 SERVICE LENGTH (yrs): 20 SERVICE LENGTH (yrs): 20 Barnett 52ft Barnett 60ft Barnett 51ft Photo credit: Beken of Cowes Beken Photo credit: of Cowes Beken Photo credit: Farr Grahame Photo credit: The 60 foot Barnett class The 51 foot Barnett class LENGTH (m): 15.8 The 52 foot Barnett class LENGTH (m): 18.3 was the largest lifeboat LENGTH (m): 15.5 was introduced soon WEIGHT (t): 28 was the final incarnation WEIGHT (t): 43 in our fleet when WEIGHT (t): 27 after its predecessor to TOP SPEED (kn): 9.5 of a lifeboat class that TOP SPEED (kn): 9.5 introduced in 1923, TOP SPEED (kn): 9.5 allow this successful served for most of the named after its designer, RANGE (nm): 300 RANGE (nm): 300 RANGE (nm): 300 boat design to launch 20th Century. -

Shipping Safety Within the Port of Liverpool Adrian Jarvis

Safe Home in Port? Shipping Safety within the Port of Liverpool Adrian Jarvis Introduction: Sources and Methods The issue of safety at sea has long exercised the minds of those who were concerned by what they perceived as irresponsible shipowners who sent their men to sea in dangerous vessels or with dangerous cargoes. Samuel Plimsoll is just the most famous among many who sought to bring to the shipping industry the sort of controls which already existed in many shore-based industries, and a number of Parliamentary enquiries investigated these questions in the nineteenth century.' Maritime historians have taken a good deal of interest in the answers, at both scholarly and more popular levels. Further down the scale comes the literature of spectacular shipwrecks, the worst examples of which are not merely voyeuristic or ghoulish but positively necrophiliac. What author of third-rate novels could improve on the real-life storyline of the Titanic? It raised issues of class and gender, of social, financial and technological hubris, and of heroism and neglect.' The common perception is that such tragic events invariably unfolded either in mid- ocean or on storm-battered rocky shores and in terms of bulk fatalities that perception is obviously correct. Its corollary, that one is safe in po rt, is not merely widely accepted but has extended to the use of the po rt as a metaphor for Heaven, with Jesus as celestial pilot and the Holy Trinity as the po rt authority.' This paper makes a rapid survey of the records of the Mersey Docks & Harbour Board (MD&HB), which shows that there obviously were accidents to ships when they were supposedly safe in po rt, that such accidents were numerous and that some of them were serious. -

Freefall Lifeboat Lifeboat Solutions

FREEFALL LIFEBOAT LIFEBOAT SOLUTIONS Survitec can supply, commission, inspect and maintain our comprehensive range of Freefall lifeboats. Designed and built to latest IMO/SOLAS and LSA regulations, our lifeboats are approved by ABS, BV, GL, LR and EC mark. The Freefall lifeboats are suitable for offshore and merchant applications including Oil and Gas tankers as well as Dry Cargo vessels. Designed for use in harsh conditions, our lifeboats are constructed using materials suited for their resistance to the corrosive marine environment. This ensures a long and trouble-free operational life with minimal maintenance required in between servicing periods. FEATURES • CAPACITIES FROM 15 TO 95 PERSONS ON BOARD (POB) • SEATING FOR AN AVERAGE BODY OF 82.5 KG (SOLAS REQUIREMENT) TO 98 KG (COMMON OFFSHORE REQUIREMENT) • TANKER AND DRY CARGO VERSIONS AVAILABLE • TANKER VERSIONS INCLUDE A COMPRESSED AIR SUPPLY TO PRESSURISE THE LIFEBOAT FOR A MINIMUM OF 10 MINUTES TO PREVENT THE INGRESS OF SMOKE AND AN EXTERNAL WATER SPRAY DELUGE SYSTEM • BUOYANCY TO SELF-RIGHT WHEN FULLY LOADED AND IN A DAMAGED CONDITION. • SUITABLE FOR OFFSHORE USE: PLATFORMS, RIGS FPSOS • DESIGNED AND BUILT TO LATEST IMO/SOLAS AND LSA REGULATIONS • SURVITEC CAN SUPPLY, COMMISSION, INSPECT AND MAINTAIN OUR COMPREHENSIVE RANGE OF FREEFALL LIFEBOATS Designed and built to latest IMO/SOLAS and LSA“ regulations. FREEFALL LIFEBOAT TECHNICAL DATA - OIL AND GAS TANKER VERSION MAX CAPACITY APPROXIMATE WEIGHT (KG) APPROXIMATE WEIGHT (KG) MODEL DIMENSIONS (M) 82. 5KG PERSONS UNLOADED LOADED -

Lifeboat Institution

ournal of the toyal National Lifeboat Institution Volume 53 Number 525 The Lifeboat \utumn 1993 Lifeboat spotter's guide Vellum service report Open Days «• SALCOMBE LIFEBOAT PRINT "BALTIC EXCHANGE II" A SPECIAL EDITION SIGNED PRINT TO COMMEMORATE A FAMOUS YEAR IN THE HISTORY OF SALCOMBE LIFEBOAT. BY GORDON ASHTON IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE SALCOMBE LIFEBOAT CREW The Inspiration As winter approaches, the early in the morning anchored amidst a Fine Art gallery distributing to residents of a picturesque Devon Resort the panorama of Salcombe estuary, he is collectors around the world. reflect on the exploits of their lifeboat always aware of the lifeboat and the cox'n Frank Smith and his crew of TV many daring rescues attributed to its The Print stars. Gathering on street corners or in fearless crew. Large Size: sleepy bars they exchange views on This painting is a result of all 35 x 24.5 inches including border events inspired by the documentary those images. And it is a lasting tribute Small Size: series. to the year of the Salcombc Lifeboat. 17 x 12.5 inches including border A stone's throw away from the lifeboat store, artist Gordon Ashton Gordon Ashton This beautiful print is reproduced pauses at his work as he hears the twin A former freelance illustrator, to a very high standard, on high quality explosions of the maroons calling the who pursued his career in Europe and art paper using light fast inks. Each print crew to action, and moments later the Australia before settling in Salcombe is hand signed by the artist and special roar of the 850 h.p. -

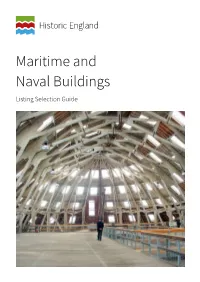

Maritime and Naval Buildings Listing Selection Guide Summary

Maritime and Naval Buildings Listing Selection Guide Summary Historic England’s twenty listing selection guides help to define which historic buildings are likely to meet the relevant tests for national designation and be included on the National Heritage List for England. Listing has been in place since 1947 and operates under the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. If a building is felt to meet the necessary standards, it is added to the List. This decision is taken by the Government’s Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). These selection guides were originally produced by English Heritage in 2011: slightly revised versions are now being published by its successor body, Historic England. The DCMS‘ Principles of Selection for Listing Buildings set out the over-arching criteria of special architectural or historic interest required for listing and the guides provide more detail of relevant considerations for determining such interest for particular building types. See https:// www.gov.uk/government/publications/principles-of-selection-for-listing-buildings. Each guide falls into two halves. The first defines the types of structures included in it, before going on to give a brisk overview of their characteristics and how these developed through time, with notice of the main architects and representative examples of buildings. The second half of the guide sets out the particular tests in terms of its architectural or historic interest a building has to meet if it is to be listed. A select bibliography gives suggestions for further reading. England has the longest coastline in relation to its land mass in Europe: nowhere is very far from the sea.