MAG-Report-0008.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

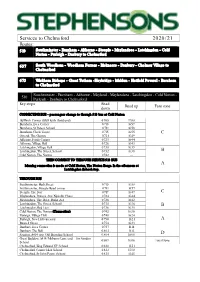

Services to Chelmsford 2020/21 Routes: 510 Southminster - Burnham - Althorne - Steeple - Maylandsea - Latchingdon - Cold Norton - Purleigh - Danbury to Chelmsford

Services to Chelmsford 2020/21 Routes: 510 Southminster - Burnham - Althorne - Steeple - Maylandsea - Latchingdon - Cold Norton - Purleigh - Danbury to Chelmsford 637 South Woodham - Woodham Ferrers - Bicknacre - Danbury - Chelmer Village to Chelmsford 673 Wickham Bishops - Great Totham -Heybridge - Maldon - Hatfield Peverel - Boreham to Chelmsford Southminster - Burnham - Althorne - Mayland - Maylandsea - Latchingdon - Cold Norton - 510 Purleigh - Danbury to Chelmsford Key stops Read Read up Fare zone down CONNECTING BUS - passengers change to through 510 bus at Cold Norton Bullfinch Corner (Old Heath Road end) 0708 1700 Burnham, Eves Corner 0710 1659 Burnham, St Peters School 0711 1658 Burnham, Clock Tower 0715 1655 C Ostend, The George 0721 1649 Althorne, Fords Corner 0725 1644 Althorne, Village Hall 0726 1643 Latchingdon, Village Hall 0730 1639 Latchingdon, The Street, School 0732 1638 B Cold Norton, The Norton 0742 -- THEN CONNECT TO THROUGH SERVICE 510 BUS A Morning connection is made at Cold Norton, The Norton Barge. In the afternoon at Latchingdon School stop. THROUGH BUS Southminster, High Street 0710 1658 Southminster, Steeple Road corner 0711 1657 Steeple, The Star 0719 1649 C Maylandsea, Princes Ave/Nipsells Chase 0724 1644 Maylandsea, The Drive, Drake Ave 0726 1642 Latchingdon, The Street, School 0735 1636 B Latchingdon, Red Lion 0736 1635 Cold Norton, The Norton (Connection) 0742 1630 Purleigh, Village Hall 0748 1624 Purleigh, New Hall vineyard 0750 1621 A Runsell Green 0754 1623 Danbury, Eves Corner 0757 1618 Danbury, The -

The Old Vicarage Ulting, Maldon, Essex the Old Vicarage

The Old Vicarage Ulting, Maldon, Essex The Old Vicarage Ulting, Maldon, Essex A stunning former vicarage in a picturesque and convenient location 5/6 bedrooms � Boiler room 2 bathrooms (1 en suite) � Cellar 3 principal reception � Ground floor cloakroom rooms � Attached coach house Study � Swimming pool Kitchen/breakfast room � Mature grounds Conservatory � About 1.15 acres Utility room Chelmsford 9.4 miles (Liverpool Street from 36 minutes) A12 3 miles (junction 20) Hatfield Peverel 2.5 miles (London Liverpool Street from 43 minutes) Ulting is a pretty village between Hatfield Peverel and Woodham Walter. Hatfield Peverel provides a good range of village amenities including a supermarket, library and a number of notable pubs and restaurants. There is also a main line railway station with services into London Liverpool Street. To the west is the city of Chelmsford and its excellent choice of amenities including a bustling shopping centre, three superb private preparatory schools, two outstanding grammar schools, a well known independent school (New Hall), a station on the main line into London Liverpool Street and access onto the A12. The Old Vicarage is a very attractive, early 19th century country house which is listed Grade II. The house is of traditional construction of gault brick with tall and distinctive lattice windows to the principal elevations providing light and airy accommodation throughout. The house is spacious and well laid out with three principal reception rooms, a kitchen/breakfast room, a conservatory, a study and a utility room. A notable feature on the ground floor is the hall, which runs the length of the house and is mirrored above on the landing. -

Pevsner's Architectural Glossary

Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 1 PEVSNER’S ARCHITECTURAL GLOSSARY Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 2 Nikolaus and Lola Pevsner, Hampton Court, in the gardens by Wren's east front, probably c. Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 3 PEVSNER’S ARCHITECTURAL GLOSSARY Yale University Press New Haven and London Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 4 Temple Street, New Haven Bedford Square, London www.pevsner.co.uk www.lookingatbuildings.org.uk www.yalebooks.co.uk www.yalebooks.com for Published by Yale University Press Copyright © Yale University, Printed by T.J. International, Padstow Set in Monotype Plantin All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections and of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 5 CONTENTS GLOSSARY Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 6 FOREWORD The first volumes of Nikolaus Pevsner’s Buildings of England series appeared in .The intention was to make available, county by county, a comprehensive guide to the notable architecture of every period from prehistory to the present day. Building types, details and other features that would not necessarily be familiar to the general reader were explained in a compact glossary, which in the first editions extended to some terms. -

Electoral Changes) Order 2004

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2004 No. 2813 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The County of Essex (Electoral Changes) Order 2004 Made - - - - 28th October 2004 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) Whereas the Boundary Committee for England(a), acting pursuant to section 15(4) of the Local Government Act 1992(b), has submitted to the Electoral Commission(c) recommendations dated April 2004 on its review of the county of Essex: And whereas the Electoral Commission have decided to give effect, with modifications, to those recommendations: And whereas a period of not less than six weeks has expired since the receipt of those recommendations: Now, therefore, the Electoral Commission, in exercise of the powers conferred on them by sections 17(d) and 26(e) of the Local Government Act 1992, and of all other powers enabling them in that behalf, hereby make the following Order: Citation and commencement 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the County of Essex (Electoral Changes) Order 2004. (2) This Order shall come into force – (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary or relating to any election to be held on the ordinary day of election of councillors in 2005, on the day after that on which it is made; (b) for all other purposes, on the ordinary day of election of councillors in 2005. Interpretation 2. In this Order – (a) The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of the Electoral Commission, established by the Electoral Commission in accordance with section 14 of the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000 (c.41). The Local Government Commission for England (Transfer of Functions) Order 2001 (S.I. -

Essex County Council (The Commons Registration Authority) Index of Register for Deposits Made Under S31(6) Highways Act 1980

Essex County Council (The Commons Registration Authority) Index of Register for Deposits made under s31(6) Highways Act 1980 and s15A(1) Commons Act 2006 For all enquiries about the contents of the Register please contact the: Public Rights of Way and Highway Records Manager email address: [email protected] Telephone No. 0345 603 7631 Highway Highway Commons Declaration Link to Unique Ref OS GRID Statement Statement Deeds Reg No. DISTRICT PARISH LAND DESCRIPTION POST CODES DEPOSITOR/LANDOWNER DEPOSIT DATE Expiry Date SUBMITTED REMARKS No. REFERENCES Deposit Date Deposit Date DEPOSIT (PART B) (PART D) (PART C) >Land to the west side of Canfield Road, Takeley, Bishops Christopher James Harold Philpot of Stortford TL566209, C/PW To be CM22 6QA, CM22 Boyton Hall Farmhouse, Boyton CA16 Form & 1252 Uttlesford Takeley >Land on the west side of Canfield Road, Takeley, Bishops TL564205, 11/11/2020 11/11/2020 allocated. 6TG, CM22 6ST Cross, Chelmsford, Essex, CM1 4LN Plan Stortford TL567205 on behalf of Takeley Farming LLP >Land on east side of Station Road, Takeley, Bishops Stortford >Land at Newland Fann, Roxwell, Chelmsford >Boyton Hall Fa1m, Roxwell, CM1 4LN >Mashbury Church, Mashbury TL647127, >Part ofChignal Hall and Brittons Farm, Chignal St James, TL642122, Chelmsford TL640115, >Part of Boyton Hall Faim and Newland Hall Fann, Roxwell TL638110, >Leys House, Boyton Cross, Roxwell, Chelmsford, CM I 4LP TL633100, Christopher James Harold Philpot of >4 Hill Farm Cottages, Bishops Stortford Road, Roxwell, CMI 4LJ TL626098, Roxwell, Boyton Hall Farmhouse, Boyton C/PW To be >10 to 12 (inclusive) Boyton Hall Lane, Roxwell, CM1 4LW TL647107, CM1 4LN, CM1 4LP, CA16 Form & 1251 Chelmsford Mashbury, Cross, Chelmsford, Essex, CM14 11/11/2020 11/11/2020 allocated. -

39177 Newsletter Issue 11 - 02/03/2015 10:53 Page 1

39177 Newsletter Issue 11_- 02/03/2015 10:53 Page 1 Newsletter Vol. 4 No. 2 – Winter 2015 Langford Village from the air Sometimes you can only appreciate the beauty of an area from above. Shapes of buildings not normally seen from ground level gain proportion when viewed from this height. This picture of Langford’s Conservation Area was taken from a Cessna, before the extensions and additions to the Village Hall were built, but it encapsulates the area well. Although many houses have been built or altered since the original settlement began, the basic layout remains the same – a linear formation along established roads with an abundance of trees and open green spaces. According to the Rev. Philip Morant (1700-1770) the historian of Essex, the parish of Langford: ‘...lies along the side of the River Pant or Blackwater, and the Long Ford here is what occasioned the name. Lang in Saxon is the same as long.’ It is otherwise written in records Langefort, Langheforda (1086 Domesday Book); Langord (1252); Longeford (1306), Lanckforde(e) (in reference to the hall in 1592).. Of course the name came from a time when the waters of the Blackwater spread over a much wider area than at present. Also, the ford today In this issue (that is just off our picture to the right) is much smaller than the original one, and Editor’s note .................................p.2 indeed no longer crosses the original River Would you like to be a Parish Councillor?...................................p.2 Blackwater. The meadow grounds bordering Places of Worship.........................p.2 the river have always been extremely fertile. -

Witham & Villages Team Ministry Parish Profile 2019

Witham & Villages Team Ministry Parish Profile 2019 St Nicolas’ Church, Witham Parish Office - Mrs Fiona Abbott Phone: 01376 791548 Email: [email protected] Website: www.withamparishchurch.org.uk W&VTM Parish Profile Jan 2020 final Table of Contents The Wider Context ............................................................................................................. 4 Witham & Villages Ministry Team: .................................................................................... 4 Current Team Members: ................................................................................................ 4 The Parish of Witham Summary:...................................................................................... 5 Aspirations ..................................................................................................................... 5 Challenges ...................................................................................................................... 6 The Team ......................................................................................................................... 6 The Team Rector: ............................................................................................................... 6 Role: ................................................................................................................................ 6 Qualities: ......................................................................................................................... 7 The Parish of Witham -

Witham and Maldon Route

Witham Attractions along the route: 8. Cressing Temple 14. Promenade Park Located at the very heart of Essex, and standing 1. Dorothy L Sayers Centre Cressing Temple was home to the elite warrior 100 year old Edwardian park with ornamental lake, on the River Brain, the manor of Witham was given This centre, based in the Library, houses a collection monks, The Knights Templar, founded in 1119 to magnificent river views and walks. Large free water to the Knights Templar in 1148. It has been a cloth of books by and about Dorothy L Sayer, novelist, protect pilgrims travelling to the Holy Land. They were Splash Park, sandpits, galleon play ship and aerial making centre, spa and coaching town. There has theologian and Dante scholar, who lived in Witham granted the Cressing site in 1137 and it became zip-wire, picnic areas and numerous events held been a market held in Witham since 1215 and a for many years. the largest and most important estate in Essex. The throughout the year. weekly market is still held today on a Saturday as Tel: 01376 519625 Templars’ were extremely powerful and acquired Tel: 01621 856503 well as a regular farmers’ market. Witham was also vast wealth, so it was here they commissioned two www.maldon.gov.uk the home of the novelist, theologian and Dante 2. St Mary & All Saints Church of the most spectacular surviving medieval timber scholar, Dorothy L Sayers and a centre has been This Saxon church is on the site of a Roman villa. The barns in Europe. -

For More Information Visit Ngs.Org.Uk

Essex gardens open for charity, 2020 Supported by For more information APPROVED INSTALLER visit ngs.org.uk 2 ESSEX ESSEX 3 Your visits to our gardens help change lives M Nurseries rley (Wakering) Ltd. In 2019 the National Garden Scheme donated £3 million to nursing and For all your gardening health charities including: Needs……. Garden centre Macmillan tea room · breakfast Cancer Marie Curie Hospice UK Support lunch & afternoon tea roses · trees · shrubs £500,000 £500,000 £500,000 seasonal bedding sheds · greenhouses arbours · fencing · trellis The Queen’s Parkinson’s Carers Trust Nursing bbq’s · water features Institute UK swimming pool & £400,000 £250,000 £500,000 spa chemicals pet & aquatic accessories plus lots more Horatio’s Perennial Mind Garden £130,000 £100,000 £75,000 We open 9am to 5pm daily Morley Nurseries (Wakering) Ltd Southend Road, Great Wakering, Essex SS3 0PU Thank you Tel 01702 585668 To find out about all our Please visit our website donations visit ngs.org.uk/beneficiaries www.morleynurseries.com 4 ESSEX ESSEX 5 Open your garden with the National Garden Scheme You’ll join a community of individuals, all passionate about their gardens, and help raise money for nursing and health charities. Big or small, if your garden has quality, character and interest we’d love to hear from you to arrange a visit. Please call [name]us on Proudly supporting 01799on [number] 550553 or or send send an an email to [email protected] to [email address] Chartered Financial Planners specialising in private client advice on: Little helpers at Brookfield • Investments • Pensions • Inheritance Tax Planning • Long Term Care Tel: 0345 319 0005 www.faireyassociates.co.uk 1st Floor, Alexandra House, 36A Church Street Great Baddow, Chelmsford, Essex CM2 7HY Fairey Associates Limited is authorised and regulated by 6 ESSEX ESSEX 7 Symbols at the end of each garden CGarden accessible to coaches. -

Chelmsford Treats and Riverside Retreats Chelmsford and Maldon Routes

Chelmsford treats and riverside retreats Chelmsford and Maldon routes Total distance of main route is 92km/57miles 14 17 2 BA 1 NTE A RS Short rides L A 22 N 0 E D 1 S B C A H O B R A 13.5km/8.4miles O 1 L A O N 0 I H N L 2 A A IG 3 13 E H M Great FIE 0 LD B 28.6km/17.8miles Leighs S LA BO N R E EH D C 18.2km/11.4miles AM ROA BO R E Ford HA M Ti ptree End D 20.4km/12.7miles R O A D D E 14.5km/9.1miles A O R E G F 19.9km/11.2miles N A BRAINTREE R Witham G G 8km/5miles ROAD 1 3 1 Chatham A Terling Witham P Green R Attractions along this route I O R D Y B A R O 2 H R O 1 Pleshey Castle Howe N C A O UR D 2 S E H Street R N C Pleshey A A B P L G 2 Chelmer & Blackwater Navigation – Paper Mill Lock ROVE T W E F R A 1 A B R R L O L M U I 3 Ulting Church T N A R R G H O D A Y D HA A L L M 2 A L ROA 2 4 Museum of Power N D 0 E 1 B B 5 Combined Military Services Museum B B 1 T O R 0 E A R I 2 E R C C O TER K 3 R H E L A H IN T EL L G H 6 The Moot Hall S D A H S M AK E ANE A O ROAD Great DR M L U E Y S A L Great R T S BU F H ASH E 1 R M Waltham O E T O E 3 Totham 7 R R A Topsail Charters LEIGHS ROAD R D 0 T B D O R S RO ER' S A O L E O EE R D A WH r H K 8 H i e Maldon District Museum D T IL v t L L e a Beacon Hill HIL r w T k c 9 e Wickham New Hall Vineyard – Purleigh BA Little a R r Hatfield l RA Bishops C 12 B T K Waltham Peverel H B A r R E 10 Marsh Farm OA A e D B S C v T i 1 K R 0 L R E 0 11 A E Tolleshunt Tropical Wings 8 N T E Hatfield Great Little D’Arcy Totham 12 RHS Garden Hyde Hall Peverel S Totham C HO 13 Essex Wildlife Trust Hanningfield -

Essex, Herts, Middlesex Kent

POST OFFICE DIRECTORY OF ESSEX, HERTS, MIDDLESEX KENT ; CORRECTED TO THE TIME OF PUBLICATION. r LONDON: PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY KELLY AND CO,, OLD BOSWELL COURT, ST. CLEMENT'S, STRAND. W.C. 1862. PREFACE. TIIE Proprietors, in submitting to their Subscribers and the Public the present (being the Fifth) Edition of the Six HOME COUNTIES DIRECTORY, trust that it may • be found to be equal in accuracy to the previous Editions. Several additions have been made to the present volume : lists of Hundreds and Poor Law Unions have been included in the Topography of each County; it is stated under each Parish in what Hundred, Union and County Court District it is situate, as well as the Diocese, Archdeaconry and Rural Deanery; and the College and University of every Beneficed Clergyman have been given. The Post Office Savings Banks have been noticed; the names of the Parish Clerks are given under each Parish ; and lists of Farm Bailiffs of gentlemen farming their own land have been added. / The bulk of the Directory has again increased considerably: the Third Edition consisted of 1,420 pages; the Fourth had increased to 1,752 pages; and the present contains 1,986 pages. The value of the Directory, however, will depend principally on the fact that it has been most carefully corrected, every parish having been personally visited by the Agents during the last six months. The Proprietors have again to return their thanks to the Clergymen, Clerks of the Peace, Magistrates' Clerks, Registrars, and other Gentlemen who have assisted the Agents while collecting the information. -

EB018 Maldon District Historic Environment Characterisation Project

HISTORICEB018 ENVIRONMENT Maldon District Historic Environment Characterisation Project 2008 abc i EB018 Front Cover: Aerial view of the Causeway onto Northey Island ii EB018 Contents FIGURES........................................................................................................................................................... VII ABBREVIATIONS .............................................................................................................................................IX ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS..................................................................................................................................X MALDON DISTRICT HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT CHARACTERISATION PROJECT..................... 11 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 11 1.1 PURPOSE OF THE PROJECT ................................................................................................................... 12 2 THE HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT OF MALDON DISTRICT .......................................................... 14 2.1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 14 3 CHARACTERISATION OF THE RESOURCE.................................................................................... 33 3.1 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT CHARACTER AREA DESCRIPTIONS.............................................................. 35 3.1.1 HECA 1 Blackwater