Watchdogs That Do Not Bite, Nets That Do Not Catch and “Perps” Policing Themselves: Why Anti-Corruption Multi-Level Governance Efforts Fail in the Philippines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philippine Election ; PDF Copied from The

Senatorial Candidates’ Matrices Philippine Election 2010 Name: Nereus “Neric” O. Acosta Jr. Political Party: Liberal Party Agenda Public Service Professional Record Four Pillar Platform: Environment Representative, 1st District of Bukidnon – 1998-2001, 2001-2004, Livelihood 2004-2007 Justice Provincial Board Member, Bukidnon – 1995-1998 Peace Project Director, Bukidnon Integrated Network of Home Industries, Inc. (BINHI) – 1995 seek more decentralization of power and resources to local Staff Researcher, Committee on International Economic Policy of communities and governments (with corresponding performance Representative Ramon Bagatsing – 1989 audits and accountability mechanisms) Academician, Political Scientist greater fiscal discipline in the management and utilization of resources (budget reform, bureaucratic streamlining for prioritization and improved efficiencies) more effective delivery of basic services by agencies of government. Website: www.nericacosta2010.com TRACK RECORD On Asset Reform and CARPER -supports the claims of the Sumilao farmers to their right to the land under the agrarian reform program -was Project Director of BINHI, a rural development NGO, specifically its project on Grameen Banking or microcredit and livelihood assistance programs for poor women in the Bukidnon countryside called the On Social Services and Safety Barangay Unified Livelihood Investments through Grameen Banking or BULIG Nets -to date, the BULIG project has grown to serve over 7,000 women in 150 barangays or villages in Bukidnon, -

28. Rights Defense and New Citizen's Movement

JOBNAME: EE10 Biddulph PAGE: 1 SESS: 3 OUTPUT: Fri May 10 14:09:18 2019 28. Rights defense and new citizen’s movement Teng Biao 28.1 THE RISE OF THE RIGHTS DEFENSE MOVEMENT The ‘Rights Defense Movement’ (weiquan yundong) emerged in the early 2000s as a new focus of the Chinese democracy movement, succeeding the Xidan Democracy Wall movement of the late 1970s and the Tiananmen Democracy movement of 1989. It is a social movement ‘involving all social strata throughout the country and covering every aspect of human rights’ (Feng Chongyi 2009, p. 151), one in which Chinese citizens assert their constitutional and legal rights through lawful means and within the legal framework of the country. As Benney (2013, p. 12) notes, the term ‘weiquan’is used by different people to refer to different things in different contexts. Although Chinese rights defense lawyers have played a key role in defining and providing leadership to this emerging weiquan movement (Carnes 2006; Pils 2016), numerous non-lawyer activists and organizations are also involved in it. The discourse and activities of ‘rights defense’ (weiquan) originated in the 1990s, when some citizens began using the law to defend consumer rights. The 1990s also saw the early development of rural anti-tax movements, labor rights campaigns, women’s rights campaigns and an environmental movement. However, in a narrow sense as well as from a historical perspective, the term weiquan movement only refers to the rights campaigns that emerged after the Sun Zhigang incident in 2003 (Zhu Han 2016, pp. 55, 60). The Sun Zhigang incident not only marks the beginning of the rights defense movement; it also can be seen as one of its few successes. -

The Failure of the Peaceful Road to Socialism: Chile 1970-1973

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1978 The aiF lure of the Peaceful Road to Socialism: Chile 1970-1973 Trevor Andrew Iles Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Political Science at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Iles, Trevor Andrew, "The aiF lure of the Peaceful Road to Socialism: Chile 1970-1973" (1978). Masters Theses. 3235. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/3235 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAPER CERTIFICATE #12 TO: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. SUBJECT: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. Date Author I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis be reproduced because--------------- Date Author pdm THE FAILURE OF THE PEACEFUL ROAD TO SOCIALifil1.__ CHILE 1970-1973 (TITLE) BY TREVOR ANDREW ILES ::;::. -

Here a Causal Relationship? Contemporary Economics, 9(1), 45–60

Bibliography on Corruption and Anticorruption Professor Matthew C. Stephenson Harvard Law School http://www.law.harvard.edu/faculty/mstephenson/ March 2021 Aaken, A., & Voigt, S. (2011). Do individual disclosure rules for parliamentarians improve government effectiveness? Economics of Governance, 12(4), 301–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-011-0100-8 Aaronson, S. A. (2011a). Does the WTO Help Member States Clean Up? Available at SSRN 1922190. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1922190 Aaronson, S. A. (2011b). Limited partnership: Business, government, civil society, and the public in the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). Public Administration and Development, 31(1), 50–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.588 Aaronson, S. A., & Abouharb, M. R. (2014). Corruption, Conflicts of Interest and the WTO. In J.-B. Auby, E. Breen, & T. Perroud (Eds.), Corruption and conflicts of interest: A comparative law approach (pp. 183–197). Edward Elgar PubLtd. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebookbatch.GEN_batch:ELGAR01620140507 Abbas Drebee, H., & Azam Abdul-Razak, N. (2020). The Impact of Corruption on Agriculture Sector in Iraq: Econometrics Approach. IOP Conference Series. Earth and Environmental Science, 553(1), 12019-. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/553/1/012019 Abbink, K., Dasgupta, U., Gangadharan, L., & Jain, T. (2014). Letting the briber go free: An experiment on mitigating harassment bribes. JOURNAL OF PUBLIC ECONOMICS, 111(Journal Article), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2013.12.012 Abbink, Klaus. (2004). Staff rotation as an anti-corruption policy: An experimental study. European Journal of Political Economy, 20(4), 887–906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2003.10.008 Abbink, Klaus. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2007 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2007 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 2007 ANNUAL REPORT VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2007 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2007 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 38–026 PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate SANDER M. LEVIN, Michigan, Chairman BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota, Co-Chairman MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio MAX BAUCUS, Montana TOM UDALL, New Mexico CARL LEVIN, Michigan MICHAEL M. HONDA, California DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIM WALZ, Minnesota SHERROD BROWN, Ohio CHRISTOPHER H. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Philippines (2010)

Page 1 of 9 Print Freedom in the World - Philippines (2010) Political Rights Score: 4 * Capital: Manila Civil Liberties Score: 3 * Status: Partly Free Population: 92,227,000 Trend Arrow The Philippines received a downward trend arrow due to a general decline in the rule of law in the greater Mindanao region, and specifically the massacre of 57 civilians on their way to register a candidate for upcoming elections. Overview Political maneuvering escalated in 2009 as potential candidates prepared for the 2010 presidential election. Meanwhile, the administration remained unsuccessful in its long-standing efforts to amend the constitution and resolve the country’s Muslim and leftist insurgencies. In November, President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo declared martial law in the southern province of Maguindanao after 57 people were massacred in an apparent bid by the area’s dominant clan to prevent the electoral registration of a rival candidate. After centuries of Spanish rule, the Philippines came under U.S. control in 1898 and won independence in 1946. The country has been plagued by insurgencies, economic mismanagement, and widespread corruption since the 1960s. In 1986, a popular protest movement ended the 14-year dictatorship of President Ferdinand Marcos and replaced him with Corazon Aquino, whom the regime had cheated out of an electoral victory weeks earlier. Aquino’s administration ultimately failed to implement substantial reforms and was unable to dislodge entrenched social and economic elites. Fidel Ramos, a key figure in the 1986 protests, won the 1992 presidential election. The country was relatively stable and experienced significant if uneven economic growth under his administration. -

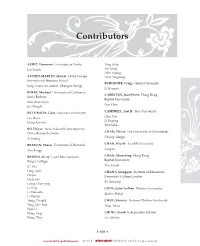

Contributors.Indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM F-479 /203/BER00069/Work/Indd/%20Backmatter

02_Contributors.indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM f-479 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter Contributors AUBIÉ, Hermann University of Turku Yang Jiang Liu Xiaobo Yao Ming Zhao Ziyang AUSTIN-MARTIN, Marcel China Europe Zhou Youguang International Business School BURGDOFF, Craig Capital University Jiang Zemin (co-author: Zhengxu Wang) Li Hongzhi BERRY, Michael University of California, CABESTAN, Jean-Pierre Hong Kong Santa Barbara Baptist University Hou Hsiao-hsien Lien Chan Jia Zhangke CAMPBELL, Joel R. Troy University BETTINSON, Gary Lancaster University Chen Yun Lee, Bruce Li Keqiang Wong Kar-wai Wen Jiabao BO Zhiyue New Zealand Contemporary CHAN, Felicia The University of Manchester China Research Centre Cheung, Maggie Xi Jinping BRESLIN, Shaun University of Warwick CHAN, Hiu M. Cardiff University Zhu Rongji Gong Li BROWN, Kerry Lau China Institute, CHAN, Shun-hing Hong Kong King’s College Baptist University Bo Yibo Zen, Joseph Fang Lizhi CHANG Xiangqun Institute of Education, Hu Jia University College London Hu Jintao Fei Xiaotong Leung Chun-ying Li Peng CHEN, Julie Yu-Wen Palacky University Li Xiannian Kadeer, Rebiya Li Xiaolin Tsang, Donald CHEN, Szu-wei National Taiwan University Tung Chee-hwa Teng, Teresa Wan Li Wang Yang CHING, Frank Independent Scholar Wang Zhen Lee, Martin • 569 • www.berkshirepublishing.com © 2015 Berkshire Publishing grouP, all rights reserved. 02_Contributors.indd Page 570 9/22/15 12:09 PM f-500 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter • Berkshire Dictionary of Chinese Biography • Volume 4 • COHEN, Jerome A. New -

Report of the Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman Or Degrading Treatment Or Punishment, Juan E

United Nations A/HRC/22/53/Add.4 General Assembly Distr.: General 12 March 2013 English/French/Spanish only Human Rights Council Twenty-second session Agenda item 3 Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development Report of the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, Juan E. Méndez Addendum Observations on communications transmitted to Governments and replies received* * The present document is being circulated in the languages of submission only. GE.13-11820 A/HRC/22/53/Add.4 Contents Paragraphs Page Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................... 5 I. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1–5 6 II. Observations by the Special Rapporteur ................................................................. 6–162 6 Angola ................................................................................................................ 6 6 Argentina ................................................................................................................ 7 7 Azerbajan ................................................................................................................ 8–9 7 Bahrain ................................................................................................................ 10–14 8 Bangladesh -

The Signal and the Noise

nieman spring 2013 Vol. 67 no. 1 Nieman Reports The Nieman Foundation for Journalism REPOR Harvard University One Francis Avenue T s Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 Nieman VOL Reports . 67 67 . To promoTe and elevaTe The sTandards of journalism n o. 1 spring 2013 o. T he signal and T he noise The SigNal aNd The NoiSe hall journalism and the future of crowdsourced reporting Carroll after the Boston marathon murdoch bombings ALSO IN THIS ISSUE Fallout for rupert mudoch from the U.K. tabloid scandal T HE Former U.s. poet laureate NIEMAN donald hall schools journalists FOUNDA Associated press executive editor T Kathleen Carroll on “having it all” ion a T HARVARD PLUS Murrey Marder’s watchdog legacy UNIVERSI Why political cartoonists pick fights Business journalism’s many metaphors TY conTEnts Residents and journalists gather around a police officer after the arrest of the Boston Marathon bombing suspect BIG IDEAS BIG CELEBRATION Please join us to celebrate 75 years of fellowship, share stories, and listen to big thinkers, including Robert Caro, Jill Lepore, Nicco Mele, and Joe Sexton, at the Nieman Foundation for Journalism’s 75th Anniversary Reunion Weekend SEPTEMBER 27–29 niEMan REPorts The Nieman FouNdatioN FoR Journalism at hARvARd UniversiTy voL. 67 No. 1 SPRiNg 2013 www.niemanreports.org PuBliShER Ann Marie Lipinski Copyright 2013 by the President and Fellows of harvard College. Please address all subscription correspondence to: one Francis Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138-2098 EdiToR James geary Periodicals postage paid at and change of address information to: Boston, Massachusetts and additional entries. SEnioR EdiToR Jan gardner P.o. -

Narrow but Endlessly Deep: the Struggle for Memorialisation in Chile Since the Transition to Democracy

NARROW BUT ENDLESSLY DEEP THE STRUGGLE FOR MEMORIALISATION IN CHILE SINCE THE TRANSITION TO DEMOCRACY NARROW BUT ENDLESSLY DEEP THE STRUGGLE FOR MEMORIALISATION IN CHILE SINCE THE TRANSITION TO DEMOCRACY PETER READ & MARIVIC WYNDHAM Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Read, Peter, 1945- author. Title: Narrow but endlessly deep : the struggle for memorialisation in Chile since the transition to democracy / Peter Read ; Marivic Wyndham. ISBN: 9781760460211 (paperback) 9781760460228 (ebook) Subjects: Memorialization--Chile. Collective memory--Chile. Chile--Politics and government--1973-1988. Chile--Politics and government--1988- Chile--History--1988- Other Creators/Contributors: Wyndham, Marivic, author. Dewey Number: 983.066 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: The alarm clock, smashed at 14 minutes to 11, symbolises the anguish felt by Michele Drouilly Yurich over the unresolved disappearance of her sister Jacqueline in 1974. This edition © 2016 ANU Press I don’t care for adulation or so that strangers may weep. I sing for a far strip of country narrow but endlessly deep. No las lisonjas fugaces ni las famas extranjeras sino el canto de una lonja hasta el fondo de la tierra.1 1 Victor Jara, ‘Manifiesto’, tr. Bruce Springsteen,The Nation, 2013. -

The Elaborate Paper Tiger: Environmental Enforcement and the Rule of Law in China

Ryan - Final (Do Not Delete) 7/21/2014 4:29 PM THE ELABORATE PAPER TIGER: ENVIRONMENTAL ENFORCEMENT AND THE RULE OF LAW IN CHINA ERIN RYAN† ABSTRACT In recent decades, the eyes of the world have been trained on China’s remarkable feats of rapid economic development. Yet the enormous environmental toll associated with China’s growth has also drawn global attention, as Chinese air and water quality plummet to historic lows. Epic levels of environmental degradation have fueled a growing domestic consensus that China must do better at reconciling these competing goals. This article reviews the contemporary challenges facing the second wave of environmental governance in China (with an addendum addressing important environmental law amendments enacted as it went to press). In the first wave of environmental governance, the government promulgated a series of environmental statutes that seem comprehensive— at least on paper. Nevertheless, it has become an article of faith among observers that they are superficially designed and too often unrealized for lack of meaningful implementation. Many environmental law and policy directives are crafted in aspirational form, and even those that do contain enforceable provisions are too often obstructed, for reasons both political and economic. When political patronage and economic interests take precedence over the faithful implementation of these laws, environmental protection suffers alongside other fundamental goals of good governance. For Chinese environmental law to succeed at its increasingly urgent objectives, it must become more than an elaborate paper tiger, moving from the present era of exhortation toward a more mature era of consistent implementation and enforcement. However change unfolds, China will have to wrestle with three basic challenges that continue to obstruct Copyright © 2014 Erin Ryan.