How They Got Away with Murder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Confession of George Atzerodt

The Confession of George Atzerodt Full Transcript (below) with Introduction George Atzerodt was a homeless German immigrant who performed errands for the actor, John Wilkes Booth, while also odd-jobbing around Southern Maryland. He had been arrested on April 20, 1865, six days after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln by John Wilkes Booth. Booth had another errand boy, a simpleton named David Herold, who resided in town. Herold and Atzerodt ran errands for Booth, such as tending horses, delivering messages, and fetching supplies. Both were known for running their mouths, and Atzerodt was known for drinking. Four weeks before the assassination, Booth had intentions to kidnap President Lincoln, but when his kidnapping accomplices learned how ridiculous his plan was, they abandoned him and returned to their homes in the Baltimore area. On the day of the assassination the only persons remaining in D.C. who had any connection to the kidnapping plot were Booth's errand boys, George Atzerodt and David Herold, plus one of the key collaborators with Booth, James Donaldson. After David Herold had been arrested, he confessed to Judge Advocate John Bingham on April 27 that Booth and his associates had intended to kill not only Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward, but Vice President Andrew Johnson as well. David Herold stated Booth told him there were 35 people in Washington colluding in the assassination. This information Herold learned from Booth while accompanying him on his flight after the assassination. In Atzerodt's confession, this band of assassins was described as a crowd from New York. -

WAD Oct 2006-Rev #2.Indd

WORLD ASSOCIATION OF DETECTIVES W.A.D. NEWS Vol. 57, Issue 3 www.wad.net October 2006 Linda Walker (Dru Sjodin’s mother) and Investigator Bob Heales searching for Dru in Winter 2003 PHOTO CREDIT: CHRIS REGIMBAL OF WDAZ TV IN GRAND FORKS, NORTH DAKOTA Inside this issue: Selecting the Right Investigator UK Robber Caught by DNA Gets 15 Years Tokyo Conference Highlights 2 WORLD ASSOCIATION OF DETECTIVES, INC. W.A.D. BOARD OF DIRECTORS 2006-2007 PAST PRESIDENTS with voting rights J D Vinson, Jr. Chairman of the Board Raymond A. Pendleton – New Orleans, Louisiana, USA Richard D. Jacques-Turner – Hull, England 955 Howard Avenue Robert A. Heales – Denver, Colorado, USA New Orleans, Louisiana Philip J. Stuto – Concord, California, USA 70113 USA Joel Michel – Burlingame, California, USA Rockne F. Cooke – Baltimore, Maryland, USA Tel: +1-504-529-2260 Werner E. Sachse – Aschaffenburg, Germany [email protected] Louis Laframboise – Laval, Quebec, Canada Jan Stekelenburg – Bavel, Netherlands John G. Talaganis – Long Beach, California, USA JD Vinson, Jr. – New Orleans, Louisiana, USA Eric Shelmerdine Term Ending 2007 Term Ending 2008 President Manuel Graf Simon Jacobs David Grimes Maureen Jacques-Turner 295-297 Church Street Gerd Hoffmann, Jr. Kimberly King Blackpool, FY1 3PJ Lothar Mueller Siti Naidu England Laura Rossi Jean Schmitt Christine Vinson Vladimir Solomanidin Tel: +44-1253-295265 Matthias Willenbrink Candice Tal [email protected] Term Ending 2009 R.P. Chauhan Jim Foster Sumio Hiroshima Lothar Kimm Allen Cardoza Fernando Molina Dato Mohamad Som Sulaiman 1st Vice President Dale Wunderlich 3857 Birch Street, Suite 208 Newport Beach, California 92660-2616 USA Parliamentarian Historian Sergeant at Arms Tel: +1-877-899-8585 Rockne F. -

How Did Booth Break His

STATE YOUR CASE (No. 2), John Elliott: How Did John Wilkes Booth Break His Leg? I believe that John Wilkes Booth did not break his leg when jumping from the balustrade to the stage at Ford’s Theatre. I support Michael Kauffman’s theory that Booth broke his Fibula when his horse fell on him after he crossed in to Maryland. First I will refute the diary entry Booth wrote during his escape, claiming he broke his leg in jumping. Booth’s version of events is filled with exaggerated claims that were written in response to newspaper articles calling him a coward. Next, I will present the first eyewitness accounts taken in the early days after the assassination that state John Wilkes Booth ran or rushed across the stage after jumping from the box. Surely a man who had just broken his leg would show some signs of pain or would limp after breaking his leg. Last, I will present the evidence that I believe shows JWB broke his leg when his horse fell on him. This includes more eyewitness accounts and medical opinions. Sources: We Saw Lincoln Shot Timothy S. Good American Brutus Mike Kauffman The Lincoln Assassination/The Evidence Edwards and Steers Jr. Booth’s Diary Entry History books tell us that John Wilkes Booth broke his leg while jumping from the balustrade of President Lincoln’s box to the stage at Ford’s Theatre. This is the most commonly held belief because John Wilkes Booth wrote that it happened that way. But should we take his word for it? A closer examination of his diary entry shows that he tried to paint a more daring and heroic image of himself during what he believed to be his crowning achievement. -

The Assassination 1 of 2 a Living Resource Guide to Lincoln's Life and Legacy

5-2 The Assassination 1 of 2 A Living Resource Guide to Lincoln's Life and Legacy The Assassination Lincoln Assassination. Clipart ETC. 18 July 2008. Educational Technology Clearinghouse. University of South Florida. <http://etc.usf.edu/clipart> March 17, 1865 John Wilkes Booth’s plot to kidnap Lincoln is foiled by Lincoln’s failure to show up at the soldiers’ hospital where Booth planned to carry out the kidnapping. April 14,1865 Booth fires his derringer the President while Lincoln, his wife Mary Todd Lincoln, Maj. Henry R. Rathbone, and his fiancée Clara Harris are in a private box in Ford’s Theater viewing a special performance of Our American Cousin. Entering through the President's left ear, the bullet lodges behind his right eye, leaving him paralyzed. Booth leaps from the box on to the stage, declaring “Sic simper tyrannis” and breaking his right fibula. Nearly simultaneously, Lewis Paine twice slashes Secretary of State William Henry Seward’s throat while the Secretary lies in bed recovering from a carriage accident. A metal surgical collar prevents the attack from accomplishing its deadly objective. Believing his attempt successful, Paine fights his way out of the mansion. Dr. Charles Leale examines the President. Lincoln is moved to a boarding house, now called the Peterson House, across Office of Curriculum & Instruction/Indiana Department of Education 09/08 This document may be duplicated and distributed as needed. 5-2 The Assassination 2 of 2 A Living Resource Guide to Lincoln's Life and Legacy from the theater on 10th Street. Co-conspirator George Atzerodt fails to carry out the plan to assassinate Vice President Andrew Johnson. -

The Lincoln Assassination

The Lincoln Assassination The Civil War had not been going well for the Confederate States of America for some time. John Wilkes Booth, a well know Maryland actor, was upset by this because he was a Confederate sympathizer. He gathered a group of friends and hatched a devious plan as early as March 1865, while staying at the boarding house of a woman named Mary Surratt. Upon the group learning that Lincoln was to attend Laura Keene’s acclaimed performance of “Our American Cousin” at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, Booth revised his mastermind plan. However it still included the simultaneous assassination of Lincoln, Vice President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William H. Seward. By murdering the President and two of his possible successors, Booth and his co-conspirators hoped to throw the U.S. government into disarray. John Wilkes Booth had acted in several performances at Ford’s Theatre. He knew the layout of the theatre and the backstage exits. Booth was the ideal assassin in this location. Vice President Andrew Johnson was at a local hotel that night and Secretary of State William Seward was at home, ill and recovering from an injury. Both locations had been scouted and the plan was ready to be put into action. Lincoln occupied a private box above the stage with his wife Mary; a young army officer named Henry Rathbone; and Rathbone’s fiancé, Clara Harris, the daughter of a New York Senator. The Lincolns arrived late for the comedy, but the President was reportedly in a fine mood and laughed heartily during the production. -

Decoding the Civil War: Engaging the Public with 19Th Century Technology & Cryptography Through Crowdsourcing and Online Educational Modules

The Huntington Library, Art Collections & Botanical Gardens Proposal to the National Historic Publications and Records Commission Decoding the Civil War: Engaging the Public with 19th Century Technology & Cryptography through Crowdsourcing and Online Educational Modules Project Summary 1. Purposes and Goals of the Project The American Civil War is perpetually fascinating to many members of the public. The goal of this project is to use the transcription and decoding of Civil War telegrams to engage new and younger audiences using crowdsourcing technology to spark their curiosity and develop new critical thinking skills. The transcription and decoding will contribute to national research as each participant will become a “citizen historian” or “citizen archivist.” Thus the project provides a model for long-term informal and formal education programs and curricula as it can be used even after the transcription and decoding is completed as a teaching model for students in inquiry-based learning. The Huntington Library respectfully requests a two-year grant from the National Historic Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) to provide partial funding for a consortium project that draws together the expertise of four different organizations—The Huntington Library, the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, North Carolina State University, and, through the University of Minnesota, Zooniverse.org (a non-profit devoted to citizen science)— each bringing unique expertise to a collaboration among libraries, museums, social studies education departments, and software developers with the following goals: 1) Engage new and younger audiences by enlisting their service as “citizen archivists” to accelerate digitization and online access to a rare collection of approximately 16,000 Civil War telegrams called The Thomas T. -

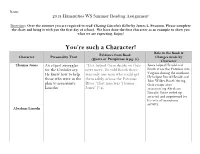

You're Such a Character!

Name:_____________________________________________ 2018 Humanities WS Summer Reading Assignment Directions: Over the summer you are required to read Chasing Lincoln’s Killer by James L. Swanson. Please complete the chart and bring it with you the first day of school. We have done the first character as an example to show you what we are expecting. Enjoy! You’re such a Character! Role in the Book & Evidence from Book Character Personality Trait Changes made by (Quote or Paraphrase & pg. #) Character Thomas Jones An expert smuggler “Cox helped them decide on their Jones helped Herold and for the Confederacy. next move. He told Booth there Booth cross the Potomac into He knew how to help was only one man who could get Virginia during the manhunt. those who were in the them safely across the Potomac He helped David Herold and John Wilkes Booth during plan to assassinate River. That man was Thomas their escape after Lincoln. Jones” (74). assassinating Abraham Lincoln. Jones ended up arrested and imprisoned for his acts of treasonous activity. Abraham Lincoln Role in the Book & Evidence from Book Character Personality Trait Changes made by (Quote or Paraphrase & pg. #) Character John Wilkes Booth Edwin Stanton George Atzerodt Role in the Book & Evidence from Book Character Personality Trait Changes made by (Quote or Paraphrase & pg. #) Character John Garrett John Surratt Role in the Book & Evidence from Book Character Personality Trait Changes made by (Quote or Paraphrase & pg. #) Character Mary Surratt Mary Todd Lincoln Role in the Book & Evidence from Book Character Personality Trait Changes made by (Quote or Paraphrase & pg. -

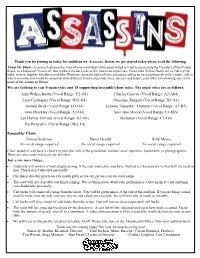

We Are Looking to Cast 9 Main Roles and 15 Supporting/Ensemble/Choir Roles

Thank you for joining us today for auditions for Assassins. Before we get started today please read the following: About the Show: Assassins lays bare the lives of nine individuals who assassinated or tried to assassinate the President of the United States, in a historical "revusical" that explores the dark side of the American experience. From John Wilkes Booth to Lee Harvey Os- wald, writers, Stephen Sondheim and John Weidman, bend the rules of time and space, taking us on a nightmarish roller coaster ride in which assassins and would-be assassins from different historical periods meet, interact and inspire each other to harrowing acts in the name of the American Dream. We are looking to cast 9 main roles and 15 supporting/ensemble/choir roles. The main roles are as follows: John Wilkes Booth (Vocal Range: F2-G4) Charles Guiteau (Vocal Range: A2-Ab4) Leon Czologosz (Vocal Range: G#2-G4) Giuseppe Zangara (Vocal Range: B2-A4) Samuel Byck (Vocal Range: D3-G4) Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme (Vocal Range: A3-B5) John Hinckley (Vocal Range: A2-G4) Sara Jane Moore (Vocal Range: F3-Eb5) Lee Harvey Oswald (Vocal Range: A2-G4) Balladeer (Vocal Range: C3-G4) The Proprietor (Vocal Range: Gb2-F4) Ensemble/ Choir: Emma Goldman David Herold Billy Moore No vocal range required No vocal range required No vocal range required Choir members will have a chance to play the roles of the presidents, tourists, news reporters, bystanders, or photographers. There are also some solo parts for the choir. Just a few more things… Auditions will consist of your prepared song. -

The Flimsy Case Against Mary Surratt: the Judicial Murder of One

The Flimsy Case Against Mary Surratt: The Judicial Murder of One of the Accused Lincoln Assassination Conspirators Michael T. Griffith 2019 @All Rights Reserved On June 30, 1865, an illegal military tribunal found Mrs. Mary Surratt guilty of conspiring with John Wilkes Booth and others to assassinate President Abraham Lincoln, and sentenced her to death by hanging. Despite numerous appeals to commute her sentence to life in prison, she was hung seven days later on July 7. She was the first woman ever to be executed by the federal government. The evidence that the military commission used as the basis for its verdict was flimsy and entirely circumstantial. Even worse, the War Department’s prosecutors withheld evidence that indicated Mrs. Surratt did not know that Booth intended to shoot President Lincoln. The prosecutors also refused to allow testimony that would have seriously impeached one of the two chief witnesses against her. Mary Surratt John Wilkes Booth, Lincoln’s assassin. He shot President Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre in Washington on April 14, 1865. The military tribunal claimed that Mary Surratt: * Knew about the assassination plot and failed to report it * On April 11, 1865, told John Lloyd that the “shooting irons” (rifles) that had been delivered to him would be needed soon 1 * An April 14, the day of the assassination, gave Lloyd a package from Booth and told him to have the rifles ready that night * Falsely claimed that she did not recognize Lewis Payne (Lewis Powell) when he showed up at her boarding house on April 17 * Falsely claimed that her youngest son, John Surratt, was not in Washington on the day of the assassination Two Plots: Kidnapping and Assassination Before we begin to examine the military commission’s case against Mary Surratt, we need to understand that Booth initiated two separate plots against Lincoln. -

Mary Surratt: the Unfortunate Story of Her Conviction and Tragic Death

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita History Class Publications Department of History 2013 Mary Surratt: The nforU tunate Story of Her Conviction and Tragic Death Leah Anderson Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/history Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Anderson, Leah, "Mary Surratt: The nforU tunate Story of Her Conviction and Tragic Death" (2013). History Class Publications. 34. https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/history/34 This Class Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Class Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mary Surratt: The Unfortunate Story of Her Conviction and Tragic Death Leah Anderson 1 On the night of April 14th, 1865, a gunshot was heard in the balcony of Ford’s Theatre followed by women screaming. A shadowy figure jumped onto the stage and yelled three now-famous words, “Sic semper tyrannis!” which means, “Ever thus to the tyrants!”1 He then limped off the stage, jumped on a horse that was being kept for him at the back of the theatre, and rode off into the moonlight with an unidentified companion. A few hours later, a knock was heard on the door of the Surratt boarding house. The police were tracking down John Wilkes Booth and his associate, John Surratt, and they had come to the boarding house because it was the home of John Surratt. An older woman answered the door and told the police that her son, John Surratt, was not at home and she did not know where he was. -

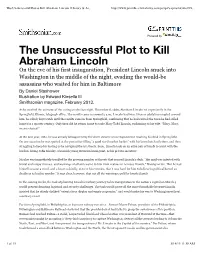

The Unsuccessful Plot to Kill Abraham Lincoln | History & Archaeology

The Unsuccessful Plot to Kill Abraham Lincoln | History & Ar... http://www.printthis.clickability.com/pt/cpt?expire=&title=Th... Powered by The Unsuccessful Plot to Kill Abraham Lincoln On the eve of his first inauguration, President Lincoln snuck into Washington in the middle of the night, evading the would-be assassins who waited for him in Baltimore By Daniel Stashower Illustration by Edward Kinsella III Smithsonian magazine, February 2013, As he awaited the outcome of the voting on election night, November 6, 1860, Abraham Lincoln sat expectantly in the Springfield, Illinois, telegraph office. The results came in around 2 a.m.: Lincoln had won. Even as jubilation erupted around him, he calmly kept watch until the results came in from Springfield, confirming that he had carried the town he had called home for a quarter century. Only then did he return home to wake Mary Todd Lincoln, exclaiming to his wife: “Mary, Mary, we are elected!” At the new year, 1861, he was already beleaguered by the sheer volume of correspondence reaching his desk in Springfield. On one occasion he was spotted at the post office filling “a good sized market basket” with his latest batch of letters, and then struggling to keep his footing as he navigated the icy streets. Soon, Lincoln took on an extra pair of hands to assist with the burden, hiring John Nicolay, a bookish young Bavarian immigrant, as his private secretary. Nicolay was immediately troubled by the growing number of threats that crossed Lincoln’s desk. “His mail was infested with brutal and vulgar menace, and warnings of all sorts came to him from zealous or nervous friends,” Nicolay wrote. -

Dr. Charles Leale

The Lincoln Assassination: Facts, Fiction and Frankly Craziness Class 2 – Dramatis personae Jim Dunphy [email protected] 1 Intro In this class, we will look at 20+ people involved in the Lincoln Assassination, both before the event and their eventual fates. 2 Intro 1. In the Box 2. Conspirators 3. At the theater 4. Booth Escape 5. Garrett Farm 3 In the Box 4 Mary Lincoln • Born in Kentucky, she was a southern belle. • Her sister was married to Ben Helm, a Confederate General killed at the battle of Chickamauga • She knew tragedy in her life as two sons died young, one during her time as First Lady • She also had extravagant tastes, and was under repeated investigation for her redecorating the White House 5 Mary Lincoln • She was also fiercely protective of her position as First Lady, and jealous of anyone she saw as a political or romantic rival • When late to a review near the end of the war and saw Lincoln riding with the wife of General Ord, she reduced Mrs. Ord to tears 6 Mary Lincoln • Later that day, Mrs.. Lincoln asked Julia Dent Grant, the wife of General Grant “I suppose you’ll get to the White House yourself, don’t you?” • When Mrs. Grant told her she was happy where she was, Mrs. Lincoln replied “Oh, you better take it if you can get it!” • As a result of these actions, Mrs.. Grant got the General to decline an invitation to accompany the Lincolns to Ford’s Theater 7 Mary Lincoln • After Lincoln was shot and moved to the Peterson House, Mrs.