On Boredom: a Note on Experience Without Qualities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Masteroppgave.Guro.Pdf (671.5Kb)

“Please Help The Cause Against Loneliness” The Importance of being a Morrissey fan Guro Flinterud Master Thesis in History of Culture Program for Culture and Ideas Studies Spring 2007 Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages, University of Oslo 2 Contents Chapter 1: Theorising Morrissey-fans……………………………………………………….5 Introduction..................................................................................................................................5 Who are The Smiths and Morrissey?...........................................................................................8 Overview of the field of fan studies……………………………………………………………11 Fans as source material………………………………………………………………………...14 Selected themes and how to reach them……………………………………………………….18 Speech genres and cultural spheres…………………………………………………………….23 Emotion and the expression of personal significance………………………………………….26 Narcissism, gender and individuality…………………………………………………………..29 Chapter 2: Fandom and love…………………………………………………………………35 The Fan and narcissism………………………………………………………………………...35 Self-reflection and the “new sort of hero”………………………………………………..........41 “Oh, I can’t help quoting you”; Morrissey in Odda……………………………………............45 The emotional dimension of music…………………………………………………………….50 Chapter 3: “I had never considered myself a normal teenager” Emotion, gender and outsiderness…………………………………………………………...56 The indie scene and masculinity………………………………………………………………..58 Morrissey fans contesting hegemonic masculinity……………………………………………..61 Non-gendered identification -

Usic We for Everyone in the Business of Music 13 MAY 1995 £2.95

usic we For Everyone in the Business of Music 13 MAY 1995 £2.95 mis WEEK 4 Yates takes ëepital at atglobal Sony rôle 6 HMV plan lapsedtargetsthe buyer 8 Rajars: the newhiiSi winnersfirst quarter 8 to Strikingan alulme a Tighblow of^m'fetener^'" Ibr Ihe UK radio Thestrong« station's audience1^0 fell to 10.5m lis- m 14 Stewart talksbis new about LP deMS 29 Venues: fordoors new open acts Capital Group's director^of program- Wright's résignation contributed to the M ^ ; S, f . MMç.sfnïïi ■eTlast^onday^p've C^itai Fa^streTsedthTthe BBC^ uresine contributiongive the Capital of Capital Grouprs: Gold a 28.69!. s fig- Parkr^rr^ia.• Kcgar profile, analys.s, next week ^pb Take Thaï race to • ri double platinum EMI Siusio regains pubiisiijgng crown tMM BackTHFiïïccess For Good ofbas the helped album propel and single Take THE ALBUM into the^inoe Party back 22.5.95 Celine Dion's ThinkTwice, ËNOdotm- tvith FMI pipping Warner chaPP^y iNCLUDES NEFiSA & 1ST ÏRANSMiSSiON of 11.8%. 100% of East 17 and Freak Power, put âssaa ss-r— ► ► ► ^ ►TWO MORE MAJORS T0DELIVEREARLY -P3 ► ► ► D P The Reactivate™ album sériés reaches a musical milestone on in what bas become the UK's best selling Nu-NRG/Trance ser.es with over 200,000 sales 10 a Formats: 12 track DJ-Friendly Double Vinyl. 12 track DJ-Friendly CD, 18 track DJ Mix CD & DJ M.x Tape mixed ^ pian. Télévision Advertising: 2 week campaign of 20 second spots on the following 1TV régions: London. Mendia , STV & Gram Kiss FM: Full 3 we^k campaign scheduled for bolh London & Manchester. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Data-Driven Structural Sequence Representations of Songs and Applications Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7dc0q8cw Author Wang, Chih-Li Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Data-Driven Structural Sequence Representations of Songs and Applications A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Electrical Engineering by Chih-Li Wang 2013 © Copyright by Chih-Li Wang 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Data-Driven Structural Sequence Representations of Songs and Applications by Chih-Li Wang Doctor of Philosophy in Electrical Engineering University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Vwani Roychowdhury, Chair Content-based music analysis has attracted considerable attention due to the rapidly growing digital music market. A number of specific functionalities, such as the exact look-up of melodies from an existing database or classification of music into well-known genres, can now be executed on a large scale, and are even available as consumer services from several well-known social media and mobile phone companies. In spite of these advances, robust representations of music that allow efficient execution of tasks, seemingly simple to many humans, such as identifying a cover song, that is, a new recording of an old song, or breaking up a song into its constituent structural parts, are yet to be invented. Motivated by this challenge, we introduce a method for determining approximate structural sequence representations purely from the chromagram of songs without adopting any prior knowledge from musicology. -

Marxman Mary Jane Girls Mary Mary Carolyne Mas

Key - $ = US Number One (1959-date), ✮ UK Million Seller, ➜ Still in Top 75 at this time. A line in red 12 Dec 98 Take Me There (Blackstreet & Mya featuring Mase & Blinky Blink) 7 9 indicates a Number 1, a line in blue indicate a Top 10 hit. 10 Jul 99 Get Ready 32 4 20 Nov 04 Welcome Back/Breathe Stretch Shake 29 2 MARXMAN Total Hits : 8 Total Weeks : 45 Anglo-Irish male rap/vocal/DJ group - Stephen Brown, Hollis Byrne, Oisin Lunny and DJ K One 06 Mar 93 All About Eve 28 4 MASH American male session vocal group - John Bahler, Tom Bahler, Ian Freebairn-Smith and Ron Hicklin 01 May 93 Ship Ahoy 64 1 10 May 80 Theme From M*A*S*H (Suicide Is Painless) 1 12 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 5 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 12 MARY JANE GIRLS American female vocal group, protégées of Rick James, made up of Cheryl Ann Bailey, Candice Ghant, MASH! Joanne McDuffie, Yvette Marine & Kimberley Wuletich although McDuffie was the only singer who Anglo-American male/female vocal group appeared on the records 21 May 94 U Don't Have To Say U Love Me 37 2 21 May 83 Candy Man 60 4 04 Feb 95 Let's Spend The Night Together 66 1 25 Jun 83 All Night Long 13 9 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 3 08 Oct 83 Boys 74 1 18 Feb 95 All Night Long (Remix) 51 1 MASON Dutch male DJ/producer Iason Chronis, born 17/1/80 Total Hits : 4 Total Weeks : 15 27 Jan 07 Perfect (Exceeder) (Mason vs Princess Superstar) 3 16 MARY MARY Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 16 American female vocal duo - sisters Erica (born 29/4/72) & Trecina (born 1/5/74) Atkins-Campbell 10 Jun 00 Shackles (Praise You) -

Michele Mulazzani's Playlist: Le 999 Canzoni Piu' Belle Del XX Secolo

Michele Mulazzani’s Playlist: le 999 canzoni piu' belle del XX secolo (1900 – 1999) 001 - patti smith group - because the night - '78 002 - clash - london calling - '79 003 - rem - losing my religion - '91 004 - doors - light my fire - '67 005 - traffic - john barleycorn - '70 006 - beatles - lucy in the sky with diamonds - '67 007 - nirvana - smells like teen spirit - '91 008 - animals - house of the rising sun - '64 009 - byrds - mr tambourine man - '65 010 - joy division - love will tear us apart - '80 011 - crosby, stills & nash - suite: judy blue eyes - '69 012 - creedence clearwater revival - who'll stop the rain - '70 013 - gaye, marvin - what's going on - '71 014 - cocker, joe - with a little help from my friends - '69 015 - fleshtones - american beat - '84 016 - rolling stones - (i can't get no) satisfaction - '65 017 - joplin, janis - piece of my heart - '68 018 - red hot chili peppers - californication - '99 019 - bowie, david - heroes - '77 020 - led zeppelin - stairway to heaven - '71 021 - smiths - bigmouth strikes again - '86 022 - who - baba o'riley - '71 023 - xtc - making plans for nigel - '79 024 - lennon, john - imagine - '71 025 - dylan, bob - like a rolling stone - '65 026 - mamas and papas - california dreamin' - '65 027 - cure - charlotte sometimes - '81 028 - cranberries - zombie - '94 029 - morrison, van - astral weeks - '68 030 - springsteen, bruce - badlands - '78 031 - velvet underground & nico - sunday morning - '67 032 - modern lovers - roadrunner - '76 033 - talking heads - once in a lifetime - '80 034 -

Mp3tag File Overview 2011-02-08

Mp3tag File Overview 2011-02-08 Title: You'll Loose A Good Thing Artist: Barbara Lynn Album: You'll Loose a Good Thing Year: 1962 Track: Genre: Oldies Comment: #8 on Billboard Hot 100 Title: Jobriath Artist: David Bowie Album: Unreleased Album (2000) Year: 2000 Track: Genre: Classic Rock Comment: Title: Freelove [Flood remix] Artist: Depeche Mode Album: Freelove Year: Track: Genre: Comment: Title: Jobriath Artist: Scott Walker & David Sylvian Album: Unreleased Album (2000) Year: 2000 Track: Genre: Classic Rock Comment: Title: La Femme D'Argent Artist: Air Album: Q - 1998-BEST Year: 1998 Track: 01 Genre: Rock Comment: Encoded by FLAC v1.1.2a with FLAC Frontend v1.7.1. Ripped by TCM Title: The State I Am In Artist: Belle And Sebastian Album: Tigermilk Year: 1996 Track: 01 Genre: Pop Comment: Track 1 Title: Lovely Day Artist: Bill Withers Album: Menagerie Year: 1977 Track: 01 Genre: Soul Comment: Title: Upp, Upp, Upp, Ner Artist: bob hund Album: bob hund Sover Aldrig [live] Year: 1999 Track: 01 Genre: Rock Comment: Encoded by FLAC v1.1.2a with FLAC Frontend v1.7.1. Ripped by TCM Title: Lloyd, I'm Ready To Be Heartbroken Artist: Camera Obscura Album: Sonically Speaking - vol. 29 Year: 2006 Track: 01 Genre: Pop Comment: Track 1 Title: Hands On The Wheel Artist: China Crisis Album: Warped By Success Year: 1994 Track: 01 Genre: Pop Comment: Track 1 Title: Geno Artist: Dexy's Midnight Runners Album: Let's Make This Precious [The Best Of] Year: 2003 Track: 01 Genre: Pop Comment: Track 1 Title: Walk On By Artist: Dionne Warwick Album: Dionne Sings Dionne Year: Track: 1 Genre: Comment: Title: Protection Artist: Massive Attack Album: Protection Year: 1994 Track: 01 Genre: Trip-Hop Comment: Encoded by FLAC v1.1.2a with FLAC Frontend v1.7.1. -

Celebrity, Gender, Desire and the World of Morrissey

" ... ONLY IF YOU'RE REALLY INTERESTED": CELEBRITY, GENDER, DESIRE AND THE WORLD OF MORRISSEY Nicholas P. Greco, B.A., M.A. Department of Art History & Communication Studies McGill University, Montreal March 2007 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Copyright © Nicholas P. Greco 2007 Library and Bibliothèque et 1+1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-32186-7 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-32186-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans loan, distribute and sell th es es le monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, électronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Morrissey Dancing a Latin Beat

V1 - AUSE01Z01MA THE AUSTRALIAN, THURSDAY, JANUARY 21, 2016 ARTS theaustralian.com.au/arts 13 Morrissey dancing a FIONA MORRISON Jukuja Dolly Snell receiving her national art award Latin beat Loved storyteller’s art Mexrrissey takes a British institution was ‘just filled with joy’ and gives his songs a Mexican feel Jukuja was among a group of AMOS AIKMAN Great Sandy Desert artists JANE CORNWELL NORTHERN CORRESPONDENT responsible for the production of the iconic Ngurrara II native title Octogenarian and spindly as a canvas in 1997. But her first show It’s the Day of the Dead in Mexico, cha to these songs gave them desert oak, she was nonetheless was not until 2014, at Outstation and down in Tobacco Dock, a vast another perspective. His songs are at the peak of her career. Gallery in Darwin. warehouse space in Wapping, strong; they stand up to reinter- Arriving in Darwin to collect the “There was this amazing East London, they’re celebrating. pretation.” A grin. “Like the works National Aboriginal and Torres thing about her, about this Thousands of hipsters working a of Shakespeare.” Strait Islander Art Award last woman from the depths of the look best described as cadaver-in- “Reactions ranged from laugh- year, Jukuja Dolly Snell insisted desert who was painting in such Victorian-dress — skeleton face ter to jumping to wild dancing to on buying a new outfit first. an extraordinary, contemporary paint, neon flower headbands, screams and tears,” wrote the Socks may have hung loose way,” Outstation’s director Matt dusty top hats and tails — are Observer.com of Mexrrissey’s around her ankles and weak legs Ward remembers. -

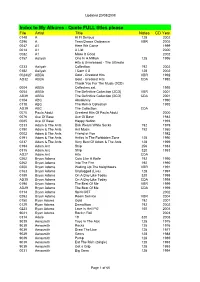

Album Backup List

Updated 20/08/2008 Index to My Albums - Quote FULL titles please File Artist Title Notes CD Year 0148 A Hi Fi Serious 128 2002 0296 A Teen Dance Ordinance VBR 2005 0047 A1 Here We Come 1999 0014 A1 A List 2000 0082 A1 Make It Good 2002 0157 Aaliyah One In A Million 128 1996 Hits & Unreleased - The Ultimate 0233 Aaliyah Collection 192 2002 0182 Aaliyah I Care 4 U 128 2002 0024/27 ABBA Gold - Greatest Hits VBR 1992 AD32 ABBA Gold - Greatest Hits CDA 1992 Thank You For The Music (3CD) 0004 ABBA Collectors set 1995 0054 ABBA The Definitive Collection (2CD) VBR 2001 AB39 ABBA The Definitive Collection (2CD) CDA 2001 0104 ABC Absolutely 1990 0118 ABC The Remix Collection 1993 AD39 ABC The Collection CDA 0070 Paula Abdul Greatest Hits Of Paula Abdul 2000 0076 Ace Of Base Ace Of Base 1983 0085 Ace Of Base Happy Nation 1993 0233 Adam & The Ants Dirk Wears White Socks 192 1979 0150 Adam & The Ants Ant Music 192 1980 0002 Adam & The Ants Friend or Foe 1982 0191 Adam & The Ants Antics In The Forbidden Zone 128 1990 0237 Adam & The Ants Very Best Of Adam & The Ants 128 1999 0194 Adam Ant Strip 256 1983 0315 Adam Ant Strip 320 1983 AD27 Adam Ant Hits CDA 0262 Bryan Adams Cuts Like A Knife 192 1990 0262 Bryan Adams Into The Fire 192 1990 0200 Bryan Adams Waking Up The Neighbours VBR 1991 0163 Bryan Adams Unplugged (Live) 128 1997 0189 Bryan Adams On A Day Like Today 320 1998 AD30 Bryan Adams On A Day Like Today CDA 1998 0198 Bryan Adams The Best Of Me VBR 1999 AD29 Bryan Adams The Best Of Me CDA 1999 0114 Bryan Adams Spirit OST 2002 0293 Bryan Adams -

The Working-Class and Post-War Britain in Pete Townshend's

Class, Youth, and Dirty Jobs: the working-class and post-war Britain in Pete Townshend’s Quadrophenia This chapter examines Pete Townshend’s Quadrophenia (1973) and the way in which it depicts continuity and change in the lives of the British working-class in the period that the album documents (1964/5), the political milieu in which it was written (1972/3), and the legacy of the concept that was depicted in the screen version directed by Franc Roddam (1978/9).1 Quadrophenia was recorded and released in a fraught period of industrial militancy in Britain that had not been witnessed since the general strike of 1926.2 The album can be ‘read’ as both a social history of an element of youth culture in the mid-1960s, but also a reflection on contemporary anxieties relating to youth, class, race, and national identity in the period 1972/3.3 Similarly, the cinematic version of Quadrophenia was conceived and directed in 1978/9 in the months prior to and after Margaret Thatcher was swept to power, ushering in a long period of Conservative politics that economically, socially, and culturally reshaped British society.4 Quadrophenia is a significant historical source for ‘reading’ these pivotal years and providing a sense of how musicians and writers were both reflecting and dramatizing a sense of ‘crisis’, ‘continuity’, and ‘change’ in working-class Britain.5 Along with the novels and films of the English ‘new wave’ and contemporary sociological examinations of working-class communities and youth culture, Quadrophenia represents a classic slice of ‘social realism’, social history, and political commentary. -

1 Giant Leap Dreadlock Holiday -- 10Cc I'm Not in Love

Dumb -- 411 Chocolate -- 1975 My Culture -- 1 Giant Leap Dreadlock Holiday -- 10cc I'm Not In Love -- 10cc Simon Says -- 1910 Fruitgum Company The Sound -- 1975 Wiggle It -- 2 In A Room California Love -- 2 Pac feat. Dr Dre Ghetto Gospel -- 2 Pac feat. Elton John So Confused -- 2 Play feat. Raghav & Jucxi It Can't Be Right -- 2 Play feat. Raghav & Naila Boss Get Ready For This -- 2 Unlimited Here I Go -- 2 Unlimited Let The Beat Control Your Body -- 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive -- 2 Unlimited No Limit -- 2 Unlimited The Real Thing -- 2 Unlimited Tribal Dance -- 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone -- 2 Unlimited Short Short Man -- 20 Fingers feat. Gillette I Want The World -- 2Wo Third3 Baby Cakes -- 3 Of A Kind Don't Trust Me -- 3Oh!3 Starstrukk -- 3Oh!3 ft Katy Perry Take It Easy -- 3SL Touch Me, Tease Me -- 3SL feat. Est'elle 24/7 -- 3T What's Up? -- 4 Non Blondes Take Me Away Into The Night -- 4 Strings Dumb -- 411 On My Knees -- 411 feat. Ghostface Killah The 900 Number -- 45 King Don't You Love Me -- 49ers Amnesia -- 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop -- 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect -- 5 Seconds Of Summer She's Kinda Hot -- 5 Seconds Of Summer Stay Out Of My Life -- 5 Star System Addict -- 5 Star In Da Club -- 50 Cent 21 Questions -- 50 Cent feat. Nate Dogg I'm On Fire -- 5000 Volts In Yer Face -- 808 State A Little Bit More -- 911 Don't Make Me Wait -- 911 More Than A Woman -- 911 Party People.. -

Steve's Karaoke Songbook

Steve's Karaoke Songbook Artist Song Title Artist Song Title +44 WHEN YOUR HEART STOPS INVISIBLE MAN BEATING WAY YOU WANT ME TO, THE 10 YEARS WASTELAND A*TEENS BOUNCING OFF THE CEILING 10,000 MANIACS CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS A1 CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE MORE THAN THIS AALIYAH ONE I GAVE MY HEART TO, THE THESE ARE THE DAYS TRY AGAIN TROUBLE ME ABBA DANCING QUEEN 10CC THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE, THE FERNANDO 112 PEACHES & CREAM GIMME GIMME GIMME 2 LIVE CREW DO WAH DIDDY DIDDY I DO I DO I DO I DO I DO ME SO HORNY I HAVE A DREAM WE WANT SOME PUSSY KNOWING ME, KNOWING YOU 2 PAC UNTIL THE END OF TIME LAY ALL YOUR LOVE ON ME 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME MAMMA MIA 2 PAC & ERIC WILLIAMS DO FOR LOVE SOS 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE SUPER TROUPER 3 DOORS DOWN BEHIND THOSE EYES TAKE A CHANCE ON ME HERE WITHOUT YOU THANK YOU FOR THE MUSIC KRYPTONITE WATERLOO LIVE FOR TODAY ABBOTT, GREGORY SHAKE YOU DOWN LOSER ABC POISON ARROW ROAD I'M ON, THE ABDUL, PAULA BLOWING KISSES IN THE WIND WHEN I'M GONE COLD HEARTED 311 ALL MIXED UP FOREVER YOUR GIRL DON'T TREAD ON ME KNOCKED OUT DOWN NEXT TO YOU LOVE SONG OPPOSITES ATTRACT 38 SPECIAL CAUGHT UP IN YOU RUSH RUSH HOLD ON LOOSELY STATE OF ATTRACTION ROCKIN' INTO THE NIGHT STRAIGHT UP SECOND CHANCE WAY THAT YOU LOVE ME, THE TEACHER, TEACHER (IT'S JUST) WILD-EYED SOUTHERN BOYS AC/DC BACK IN BLACK 3T TEASE ME BIG BALLS 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP DIRTY DEEDS DONE DIRT CHEAP 50 CENT AMUSEMENT PARK FOR THOSE ABOUT TO ROCK (WE SALUTE YOU) CANDY SHOP GIRLS GOT RHYTHM DISCO INFERNO HAVE A DRINK ON ME I GET MONEY HELLS BELLS IN DA