On James Gunn's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neues Textdokument (2).Txt

Filmliste Liste de filme DVD Münchhaldenstrasse 10, Postfach 919, 8034 Zürich Tel: 044/ 422 38 33, Fax: 044/ 422 37 93 www.praesens.com, [email protected] Filmnr Original Titel Regie 20001 A TIME TO KILL Joel Schumacher 20002 JUMANJI 20003 LEGENDS OF THE FALL Edward Zwick 20004 MARS ATTACKS! Tim Burton 20005 MAVERICK Richard Donner 20006 OUTBREAK Wolfgang Petersen 20007 BATMAN & ROBIN Joel Schumacher 20008 CONTACT Robert Zemeckis 20009 BODYGUARD Mick Jackson 20010 COP LAND James Mangold 20011 PELICAN BRIEF,THE Alan J.Pakula 20012 KLIENT, DER Joel Schumacher 20013 ADDICTED TO LOVE Griffin Dunne 20014 ARMAGEDDON Michael Bay 20015 SPACE JAM Joe Pytka 20016 CONAIR Simon West 20017 HORSE WHISPERER,THE Robert Redford 20018 LETHAL WEAPON 4 Richard Donner 20019 LION KING 2 20020 ROCKY HORROR PICTURE SHOW Jim Sharman 20021 X‐FILES 20022 GATTACA Andrew Niccol 20023 STARSHIP TROOPERS Paul Verhoeven 20024 YOU'VE GOT MAIL Nora Ephron 20025 NET,THE Irwin Winkler 20026 RED CORNER Jon Avnet 20027 WILD WILD WEST Barry Sonnenfeld 20028 EYES WIDE SHUT Stanley Kubrick 20029 ENEMY OF THE STATE Tony Scott 20030 LIAR,LIAR/Der Dummschwätzer Tom Shadyac 20031 MATRIX Wachowski Brothers 20032 AUF DER FLUCHT Andrew Davis 20033 TRUMAN SHOW, THE Peter Weir 20034 IRON GIANT,THE 20035 OUT OF SIGHT Steven Soderbergh 20036 SOMETHING ABOUT MARY Bobby &Peter Farrelly 20037 TITANIC James Cameron 20038 RUNAWAY BRIDE Garry Marshall 20039 NOTTING HILL Roger Michell 20040 TWISTER Jan DeBont 20041 PATCH ADAMS Tom Shadyac 20042 PLEASANTVILLE Gary Ross 20043 FIGHT CLUB, THE David -

Robert Wise's the Day the Earth Stood Still Part I

Robert Wise’s The Day the Earth Stood Still Part I: A Religious Film? By Anton Karl Kozlovic Fall 2013 Issue of KINEMA ROBERT WISE’S THE DAY THE EARTH STOOD STILL Part I: A RELIGIOUS FILM? Abstract Science fiction (SF) films have frequently been the home for subtextual biblical characters, particularly Christ-figures. Crafting these sacred subtexts can make the difference between an ordinary filmandan exceptional one. This investigation intends to explore the religious and other dimensions of the 1951 SF cult classic The Day the Earth Stood Still directed by Robert Wise. In Part 1 of this analytical triptych, the film’s reception as a UFO film with political, artificial intelligence (AI), police and philosophical dimensions was canvassed. It was argued that Wise’s film contains all of the above genre dimensions; however, it can bemore fully appreciated as a profoundly religious film wrapped in contemporary scientific garb. The forthcoming parts will explore the factual elements of this proposition in far greater analytical detail. Introduction: SF and Sacred Storytelling Historically speaking, science fiction (SF) films(1) have harboured numerous hidden biblical characters in typically covert forms. For example, Barry McMillan described many an SF alien as ”a ’transcendent’ being - a benign entity who brings wisdom and knowledge, the imparting of which brings resolution, insight and the beginnings of personal or political harmony” (360). Whilst Bonnie Brain argued that: ”The ascendancy of the aliens derives strongly from their aura of religious authority. Teachers, mystics, priests, or prophets, capable of ”miracles” and, in some cases, ”resurrection,” these aliens flirt with divinity” (226). -

Searching for Extraterrestrial Intelligence

THE FRONTIERS COLLEctION THE FRONTIERS COLLEctION Series Editors: A.C. Elitzur L. Mersini-Houghton M. Schlosshauer M.P. Silverman J. Tuszynski R. Vaas H.D. Zeh The books in this collection are devoted to challenging and open problems at the forefront of modern science, including related philosophical debates. In contrast to typical research monographs, however, they strive to present their topics in a manner accessible also to scientifically literate non-specialists wishing to gain insight into the deeper implications and fascinating questions involved. Taken as a whole, the series reflects the need for a fundamental and interdisciplinary approach to modern science. Furthermore, it is intended to encourage active scientists in all areas to ponder over important and perhaps controversial issues beyond their own speciality. Extending from quantum physics and relativity to entropy, consciousness and complex systems – the Frontiers Collection will inspire readers to push back the frontiers of their own knowledge. Other Recent Titles Weak Links Stabilizers of Complex Systems from Proteins to Social Networks By P. Csermely The Biological Evolution of Religious Mind and Behaviour Edited by E. Voland and W. Schiefenhövel Particle Metaphysics A Critical Account of Subatomic Reality By B. Falkenburg The Physical Basis of the Direction of Time By H.D. Zeh Mindful Universe Quantum Mechanics and the Participating Observer By H. Stapp Decoherence and the Quantum-To-Classical Transition By M. Schlosshauer The Nonlinear Universe Chaos, Emergence, Life By A. Scott Symmetry Rules How Science and Nature are Founded on Symmetry By J. Rosen Quantum Superposition Counterintuitive Consequences of Coherence, Entanglement, and Interference By M.P. -

Appendix Relations with Alien Intelligences – the Scientific Basis of Metalaw1

Appendix Relations with Alien Intelligences – The Scientific Basis of Metalaw1 Ernst Fasan DK 340.114:341.229:2:133 1 The appendix was previously published by Berlin Verlag Arno Spitz in 1970. © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016 181 P.M. Sterns, L.I. Tennen (eds.), Private Law, Public Law, Metalaw and Public Policy in Space, Space Regulations Library 8, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-27087-6 Contents Foreword by Wernher von Braun ����������������������������������������������������������������� 185 Introduction ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 187 I: The Possibility of Encountering Nonhuman Intelligent Beings �������������� 189 Opinions in Ancient Literature ��������������������������������������������������������������������� 189 The Results of Modern Science �������������������������������������������������������������� 191 II: The Physical Nature of Extraterrestrial Beings �������������������������������������� 205 The Necessary Characteristics ��������������������������������������������������������������������� 205 Origin and Development of Protoplasmic Life ��������������������������������������� 209 Intelligent Machines – The Question of Robots �������������������������������������� 210 III: The Concept, Term, and Literature of Metalaw ����������������������������������� 213 Selection and Definition of the Term ����������������������������������������������������������� 213 A Survey of Literature ����������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

LAURENT BEN-MIMOUN CONCEPTUAL ILLUSTRATION, 3D CONCEPT DESIGN MATTE PAINTING, ART DIRECTION Portfolios

LAURENT BEN-MIMOUN CONCEPTUAL ILLUSTRATION, 3D CONCEPT DESIGN MATTE PAINTING, ART DIRECTION Portfolios: www.blueman.ws www.artstation.com/artist/blueman FILM DIRECTOR PRODUCTION/Reported To “ANT-MAN AND THE WASP” PEYTON REED MARVEL STUDIOS Concept Illustrator PD: Shepherd Frankel “STARFALL” JOE JOHNSTON DI BONAVENTURA PICTURES Conceptual Art/Illustrations PD: Barry Robinson “THOR: RAGNAROK” TAIKA WAITITI MARVEL STUDIOS Conceptual Art Director PD: Dan Hennah “THE DARK TOWER” NIKOLAJ ARCEL SONY PICTURES Concept Illustrator MEDIA RIGHTS CAPITAL PD: Dan Hennah, Chris Glass “ALICE IN WONDERLAND: THROUGH JAMES BOBIN WALT DISNEY PICTURES THE LOOKING GLASS” Director: James Bobin Concept Design for Prep & Post PD: Dan Hennah & Film Book Art “GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: VOL. 2” JAMES GUNN MARVEL STUDIOS Concept Illustrator PD: Scott Chamblis “PASSENGERS” MORTEN TYLDUM COLUMBIA PICTURES Concept Illustrator PD: Guy Dyas Production Design received an Academy Award nomination and WON the Art Directors Guild Award “INDEPENDENCE DAY: RESURGENCE” ROLAND EMMERICH TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX Concept Illustrator Director: Roland Emmerich 3D Designs/Concept Art PD: Barry Chusid “GHOSTBUSTERS” PAUL FEIG COLUMBIA PICTURES Concept Illustrator PD: Jefferson Sage ‘ORPHANS OF THE VOID” Spec Pilot K. MICHEL PARANDI K. MICHEL PARANDI Concept/3D/Art Director “THE ARK AND THE AARDVARK” JOHN STEVENSON UNIFIED PICTURES Visual Development (Animation) “BRILLIANCE” JULIUS ONAH LEGENDARY PICTURES Concept Illustrator PD: Dominic Watkins “UNTITLED GHOSTBUSTERS III” IVAN REITMAN COLUMBIA -

The Drake Puzzle by Shane L

The Drake Puzzle by Shane L. Larson Department of Astronomy, Adler Planetarium “Our sun is one of 100 billion stars in our galaxy. Our galaxy is one of billions of galaxies populating the universe. It would be the height of presumption to think that we are the only living things in that enormous immensity.” ∼ Wernher von Braun Introduction The Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) has long been of interest to humankind. The problem is how would we communicate with extraterrestrial biological entities (EBEs) if we met them? It is said that in 1820, the famous German mathematician Karl Friedrich Gauss recommended that a giant right triangle of trees be planted in the Russian wilderness, an exercise that would demonstrate to EBEs that the inhabitants of Earth were civilized enough to understand geometry. It is also said that 20 years later, the Viennese astronomer Joseph von Littrow proposed digging a twenty-mile-long ditch in the Sahara, filling it with kerosene, and lighting it at night, again to communicate that there was intelligent life down here. In the modern era, the American radio astronomer Frank Drake is generally credited with beginning the first serious efforts geared toward communication with possible extraterrestrial intelligences. In 1960, at the Green Bank radio astronomy facility in West Virginia, he began the first modern search for radio signals of extraterrestrial origin, called Project Ozma. Communication without preamble In the years that followed Project Ozma, there was a great deal of debate as to whether or not we could actually decode a message if we received it, and even more to the point, whether or not an EBE could decode a message from us if it received one. -

AA-Postscript.Qxp:Layout 1

36 MONDAY, AUGUST 18, 2014 LIFESTYLE Gossip Jessica Alba is a prude essica Alba admits she is still a “real prude.” The ‘Sin City: A Dame To Kill For’ actress - who Jreprises her role as stripper Nancy Callahan in the sequel - insists that, despite being cast in a number of sexy roles, she is nothing like her characters in real life. She said: “The key word is play - everyone who knows me well knows that I’m a real prude. But a good director can make a scene look sexy without me taking off my top.” The 33-year-old actress - who has children Honor, six, and Haven, two, with husband Cash Warren - also insists she isn’t perfect and finds it a challenge to juggle her busy career and motherhood but thinks it is important to be a good role model for her daughters by doing both. She added in an interview with America’s OK! magazine: “I’m very lucky I have a lot of help. As women, we have to accept that we can’t do it all. It’s important to show our daughters that there’s more to each of us than just being a mother.” Pattinson had limited Rover diet obert Pattinson lived on a diet of bread and barbecue sauce while filming ‘The Rover’. The R28-year-old actor insists he didn’t mind shooting the movie - in which he plays a troubled man who is left for dead by his brother in the Australian outback - in remote surroundings because he found it so peaceful. -

SETI in VIVO: TESTING the WE-ARE-THEM HYPOTHESIS ∗ MAXIM A.MAKUKOV1 and VLADIMIR I

PREPRINT VERSION JULY 12, 2017. ACCEPTED IN THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ASTROBIOLOGY Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 01/23/15 DOI: 10.1017/S1473550417000210 SETI IN VIVO: TESTING THE WE-ARE-THEM HYPOTHESIS ∗ MAXIM A. MAKUKOV1 and VLADIMIR I. SHCHERBAK2 ABSTRACT After it was proposed that life on Earth might descend from seeding by an earlier extraterrestrial civilization motivated to secure and spread life, some authors noted that this alternative offers a testable implication: microbial seeds could be intentionally supplied with a durable signature that might be found in extant organisms. In particular, it was suggested that the optimal location for such an artifact is the genetic code, as the least evolving part of cells. However, as the mainstream view goes, this scenario is too speculative and cannot be meaningfully tested because encoding/decoding a signature within the genetic code is something ill-defined, so any retrieval attempt is doomed to guesswork. Here we refresh the seeded-Earth hypothesis in light of recent observations, and discuss the motivation for inserting a signature. We then show that “biological SETI” involves even weaker assumptions than traditional SETI and admits a well-defined methodological framework. After assessing the possibility in terms of molecular and evolutionary biology, we formalize the approach and, adopting the standard guideline of SETI that encoding/decoding should follow from first principles and be convention-free, develop a universal retrieval strategy. Applied to the canonical genetic code, it reveals a nontrivial precision structure of interlocked logical and numerical attributes of systematic character (previously we found these heuristically). To assess this result in view of the initial assumption, we perform statistical, comparison, interdependence, and semiotic analyses. -

FRANK D. DRAKE Education 1952 Cornell University BA, Engineering

Biographical Sketch FRANK D. DRAKE Education 1952 Cornell University B.A., Engineering Physics (with honors) 1956 Harvard University M.S., Astronomy 1958 Harvard University Ph.D., Astronomy Professional Employment 1952-1956 U.S. Navy, Electronics Officer 1956-1958 Agassiz Station Radio Astronomy Project, Harvard University 1958-1963 National Radio Astronomy Observatory, Green Bank, West Virginia - Head of Telescope Operations & Scientific Services Division - Conducted planetary research and cosmic radio source studies 1963-64 Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Chief of Lunar & Planetary Sciences 1964-1984 Cornell University - Associate Professor of Astronomy (1964); then Full Professor (1966) - Associate Director, Center for Radiophysics & Space Research (1964-75) - Director, Arecibo Observatory, Arecibo, Puerto Rico (1966-1968) - Chairman, Astronomy Department, Cornell University (1969-71) - Director, National Astronomy & Ionosphere Center, part of which is the Arecibo Observatory (from its creation in 1970 until July 1981) - Goldwin Smith Professor of Astronomy, Cornell University (1976-84) 1984-Present University of California, Santa Cruz - Dean, Natural Sciences Division (1984-1988) - Acting Associate Vice Chancellor, University Advancement (1989-90) - Professor of Astronomy & Astrophysics (1984 – 1996) - Professor Emeritus of Astronomy & Astrophysics, (1996 –present) 1984-Present SETI Institute, Mountain View, California: - President (1984-2000) - Chairman, Board of Trustees, (1984-2003) - Chairman Emeritus, Board of Trustees, 2003- present - Director, Carl Sagan Center for the Study of Life in the Universe, 2004-present Professional Achievements 1959 Shared in the discovery of the radiation belts of Jupiter, and conducted early pulsar observational studies 1960 Conducted Project OZMA at NRAO, Green Bank, WV -- the first organized search for ETI signals 1961 Devised widely-known Drake Equation, giving an estimate of the number of communicative extraterrestrial civilizations that we might find in our galaxy. -

JOHN BLAKE Make-Up Artist IATSE 706

JOHN BLAKE Make-Up Artist IATSE 706 FILM UNTITLED AVENGERS MOVIE Department Head Marvel Studios Director: Joe and Anthony Russo Cast: Robert Downey Jr., Elizabeth Olsen, Cobie Smulders, Paul Bettany, Haley Atwell AVENGERS: INFINITY WAR Department Head Marvel Studios Director: Joe and Anthony Russo Cast: Robert Downey Jr., Elizabeth Olsen, Cobie Smulders, Paul Bettany SPIDER-MAN HOMECOMING Personal Make-Up Artist to Robert Downey Jr. Columbia Pictures Director: John Watts GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY VOL. 2 Department Head Marvel Studios Director: James Gunn Cast: Sylvester Stallone, Kurt Russell, Elizabeth Debicki, Sean Gunn, Tommy Flanagan, Laura Haddock, Glenn Close, Sharon Stone Nominated: Saturn Award for Best Make-Up Nominated: Hollywood Make-Up Artist and Hair Stylist Guild Awards for Best Special Make-Up effects – Feature length Motion Picture Nominated: OFTA Film Award for Best Make-Up and Hairstyling Nominated: ACCA for Best Make-Up and Hairstyling CAPTAIN AMERICA: CIVIL WAR Department Head & Marvel Studios Personal Make-Up Artist to Robert Downey Jr. Directors: Anthony Russo, Joe Russo Cast: Robert Downey Jr., Chadwick Boseman, Paul Bettany, Emily VanCamp, Frank Grillo JANE GOT A GUN Personal Make-Up Artist to Natalie Portman and Relativity Media Joel Edgerton Director: Gavin O’Connor AVENGERS: AGE OF ULTRON Personal Make-Up Artist to Robert Downey Jr. Marvel Studios Director: Joss Whedon THE JUDGE Personal Make-Up Artist to Robert Downey Jr. Warner Bros. Director: David Dobkin IRON MAN 3 Personal Make-Up Artist to Robert Downey -

An Evolving Astrobiology Glossary

Bioastronomy 2007: Molecules, Microbes, and Extraterrestrial Life ASP Conference Series, Vol. 420, 2009 K. J. Meech, J. V. Keane, M. J. Mumma, J. L. Siefert, and D. J. Werthimer, eds. An Evolving Astrobiology Glossary K. J. Meech1 and W. W. Dolci2 1Institute for Astronomy, 2680 Woodlawn Drive, Honolulu, HI 96822 2NASA Astrobiology Institute, NASA Ames Research Center, MS 247-6, Moffett Field, CA 94035 Abstract. One of the resources that evolved from the Bioastronomy 2007 meeting was an online interdisciplinary glossary of terms that might not be uni- versally familiar to researchers in all sub-disciplines feeding into astrobiology. In order to facilitate comprehension of the presentations during the meeting, a database driven web tool for online glossary definitions was developed and participants were invited to contribute prior to the meeting. The glossary was downloaded and included in the conference registration materials for use at the meeting. The glossary web tool is has now been delivered to the NASA Astro- biology Institute so that it can continue to grow as an evolving resource for the astrobiology community. 1. Introduction Interdisciplinary research does not come about simply by facilitating occasions for scientists of various disciplines to come together at meetings, or work in close proximity. Interdisciplinarity is achieved when the total of the research expe- rience is greater than the sum of its parts, when new research insights evolve because of questions that are driven by new perspectives. Interdisciplinary re- search foci often attack broad, paradigm-changing questions that can only be answered with the combined approaches from a number of disciplines. -

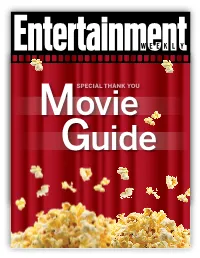

SPECIAL THANK YOU Mo V I E B:11” S:10” Gu I D E T:11” 2017 MOVIE GUIDE

SPECIAL THANK YOU Mo v i e B:11” S:10” Gu i d e T:11” 2017 MOVIE GUIDE - Amityville: The Awakening (1/6) Directed by Franck Khalfoun - Starring Bella Thorne, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Jennifer Morrison - Mena (1/6) Directed by Doug Liman - Starring Tom Cruise, Jesse Plemons - Underworld: Blood Wars (1/6) Directed by Anna Foerster - Starring Theo James, Kate Beckinsale, Charles Dance, Tobias Menzies - Hidden Figures (1/13) JANUARY Directed by Theodore Melfi -Starring Taraji P. Henson, Octavia Spencer, Kirsten Dunst, Jim Parsons, Kevin Costner - Live By Night (1/13) Directed by Ben Affleck - Starring Zoe Saldana, Scott Eastwood, Ben Affleck, Elle Fanning, Sienna Miller - Monster Trucks (1/13) Directed by Chris Wedge - Starring Jane Levy, Amy Ryan, Lucas Till, Danny Glover, Rob Lowe B:11” S:10” T:11” - The Founder (1/20) Directed by John Lee Hancock - Starring Michael Keaton - The Resurrection of Gavin Stone (1/20) Directed by Dallas Jenkins - Starring Nicole Astra, Brett Dalton - Split (1/20) Directed by M. Night Shyamalan - Starring James McAvoy, Anya Taylor Joy - Table 19 (1/20) Directed by Jeffrey Blitz - Starring Anna Kendrick, Craig Robinson, June Squibb, Lisa Kudrow - xXx: The Return of Xander Cage (1/20) Directed by D.J. Caruso - Starring Toni Collette, Vin Diesel, Tony Jaa, Samuel L. Jackson - Bastards (1/27) Directed by Larry Sher - Starring Glenn Close, Ed Helms, Ving Rhames, J.K. Simmons, Katt Williams, Owen Wilson - A Dog’s Purpose (1/27) Directed by Lasse Hallstrom - Starring Peggy Lipton, Dennis Quaid, Britt Robertson - The Lake (1/27) Directed by Steven Quale - Starring Sullivan Stapleton - Resident Evil: The Final Chapter (1/27) Directed by Paul W.S.