The Great Trial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orari E Percorsi Della Linea Bus 3107

Orari e mappe della linea bus 3107 3107 Brusasco Visualizza In Una Pagina Web La linea bus 3107 (Brusasco) ha 16 percorsi. Durante la settimana è operativa: (1) Brusasco: 13:10 - 17:25 (2) Casalborgone Scuole: 07:35 - 14:30 (3) Chivasso Istituto Ubertini: 09:10 - 13:20 (4) Chivasso Movicentro: 08:15 (5) Chivasso Movicentro: 06:50 - 12:10 (6) Chivasso Via Po: 09:10 - 19:35 (7) Chivasso Via Po: 05:15 - 21:20 (8) Gassino: 10:20 - 17:50 (9) Piana San Raffaele: 13:50 - 17:20 (10) Piovà Massaia: 17:55 (11) Torino Via Fiochetto: 06:05 - 22:15 Usa Moovit per trovare le fermate della linea bus 3107 più vicine a te e scoprire quando passerà il prossimo mezzo della linea bus 3107 Direzione: Brusasco Orari della linea bus 3107 65 fermate Orari di partenza verso Brusasco: VISUALIZZA GLI ORARI DELLA LINEA lunedì 13:10 - 17:25 martedì 13:10 - 17:25 Torino (Via Fiochetto - Autostazione Dora) 30 Lungo Dora Savona, Torino mercoledì 13:10 - 17:25 Pisa giovedì 13:10 - 17:25 109 Lungo Dora Firenze, Torino venerdì 13:10 - 17:25 Gtt Stabilimento Tortona sabato 13:10 - 15:30 54/E Corso Tortona, Torino domenica 06:55 - 17:30 Tortona 28 Corso Belgio, Torino Chieti 60/D Corso Belgio, Torino Informazioni sulla linea bus 3107 Direzione: Brusasco Brianza Fermate: 65 96 /B Corso Belgio, Torino Durata del tragitto: 75 min La linea in sintesi: Torino (Via Fiochetto - Cadore Autostazione Dora), Pisa, Gtt Stabilimento Tortona, 166 Corso Belgio, Torino Tortona, Chieti, Brianza, Cadore, Pasini, Mongreno, Sassi-Superga, Cafasso, Casale N.472, Croce, Pasini Pescatori, Delle Pietre, La Valle, Diaz, Casale N.33, Piazza Alberto Pasini, Torino San Mauro (Scambio Peso), San Mauro (Sambuy), Castiglione (Molino), Castiglione (Pedaggio), Mongreno Castiglione (Fornace), Castiglione (Rezza), 310 Corso Casale, Torino Castiglione (Sant' Eufemia), Gassino (Circonvallazione / Diaz), Gassino (Centro), Gassino Sassi-Superga (Sobrero), Gassino (V. -

Slope Instability and Flood Events in the Sangone Valley, Northwest Italian Alps

77 STUDIA GEOMORPHOLOGICA CARPATHO-BALCANICA Vol. XLIV, 2010: 77–112 PL ISSSN 0081-6434 LANDFORM EVOLUTION IN MOUNTAIN AREAS 1 1 1 MARCELLA BIDDOCCU , LAURA TURCONI , DOMENICO TROPEANO , 2 SUNIL KUMAR DE (TORINO) SLOPE INSTABILITY AND FLOOD EVENTS IN THE SANGONE VALLEY, NORTHWEST ITALIAN ALPS Abstract. Slope instability and streamflow processes in the mountainous part of the SanGone river basin have been investiGated in conjunction with their influence on relief remodellinG. ThrouGh histor- ical records, the most critical sites durinG extreme rainfalls have been evidenced, concerned natural parameters and their effects (impact on man-made structures) reiterated over space and time. The key issue of the work is the simulation of a volume of detrital materials, which miGht be set in motion by a debris flow. Two modellinG approaches have been tested and obtained results have been evaluated usinG Debris © (GEOSOFT s.a.s.) software. Simulation of debris flow in a small sub-catchment (Tauneri stream) was carried out and the thickness of sediment “packaGe” that could be removed was calculated in order to assess the debris flow hazard. The Turconi & Tropeano formula (2000) was applied to all the partitions of the SanGone basin in order to predict the whole sediment volume which miGht be delivered 3 to the main stream durinG an extreme event and the result beinG 117 m /hectare. Key words : landslip, torrential flood, debris flow, predictive model INTRODUCTION The Alpine valleys, throughout centuries, are in search of an equilibrium between anthropogenic activity and natural processes; interventions due to ameliorating productivity, accommodation and safety conditions for Man and environment often were done overlapping or contrasting the slowly-operating exogenous agents. -

Strategia Per Le Valli Di Lanzo Strategia Nazionale Per Le Aree Interne

STRATEGIA NAZIONALE PER LE AREE INTERNE LA MONTAGNA SI AVVICINA STRATEGIA PER LE VALLI DI LANZO SETTEMBRE 2020 strategia nazionale per le aree interne Strategia per le Valli di Lanzo Il passato recente e il futuro prossimo La realtà socioeconomica territoriale e le sue dinamiche evolvono rapidamente, spesso più rapidamente delle idee e delle strategie che ne sono a fondamento, sempre più velocemente della percezione che anche un osservatore attento riesce ad avere del mutamento stesso. Nel periodo intercorso tra l’approvazione della Bozza di Strategia (28 Settembre 2018) e la redazione della Strategia d’Area, di seguito presentata, il mondo nella sua globalità ha vissuto una delle fasi più drammatiche registrate negli ultimi decenni, ma nel contempo più propulsive, pur nella preoccupante contabilizzazione di dati econometrici negativi e della ancor più tragica registrazione dei decessi correlati alla pandemia di COVID 19. Il territorio dell’Area Interna delle Valli di Lanzo non solo non è stato esente dal diffuso fenomeno epidemiologico e dalle relative conseguenze dell’impatto negativo subito dalle famiglie, dalle imprese, dal tessuto sociale nel suo complesso e ancor più dal tessuto economico. Il territorio tutto ha registrato - forse si comincia ad averne contezza solo ora - nuove tendenze e mutamenti di ruoli, possibilità di azione e di abitudini più marcate rispetto ad altre aree montane, in quanto la realtà locale è strettamente correlata con il tessuto cittadino di Torino e di tutta l’area metropolitana torinese. In tal senso, le Valli di Lanzo nella loro accezione più ampia e il territorio della Città Metropolitana, sono da sempre caratterizzati da una forte correlazione con maggiori rapporti di biunivocità rispetto a quanto possa darne conto un primo sguardo: pendolarismo per lavoro e studio, flusso di merci da e verso le valli, fruizione turistica e frequentazione occasionale, seconde case e storicità di presenza, senso di appartenenza e di comunità. -

Eternit and the Great Asbestos Trial: Chap.7

Table of Contents Eternit in Italy – the Asbestos Trial in Turin 7. A TRIAL WITH FAR-REACHING IMPLICATIONS Laurent Vogel1 On 4 July 2011, Turin public prosecutor Raffaele Guar- ment through knowledge comes through with clarity in iniello concluded his statement of case by calling for the detail with which the trial was able to delve into the 20-year jail sentences against the two men in the dock – history of working conditions, the business organization Swiss billionaire Stephan Schmidheiny and Belgium’s and the health impacts of Eternit’s business. It was an Baron Louis de Cartier de Marchienne. indispensable foundation for an innovative reinterpreta- tion of classical legal concepts like causality, liability The Turin trial is special – obviously not for being the and deliberate tortious intent. first time the asbestos industry has found itself in the dock, but rather due to the conflation of three things: The wide-ranging judicial investigation unearthed 2,969 cases – more than 2,200 deaths and some 700 cancer 1. It is the outcome of nearly half a century’s direct sufferers. The roll of death in Casale Monferrato reads: worker action for criminal justice driven basic- around 1,000 Eternit workers, 500 local residents and ally by Eternit’s Casale Monferrato factory work- 16 sub-contract workers. Added to those are some 500 ers. cases in Bagnoli near Naples, 100 in Cavagnolo in the 2. It is a criminal trial focused on the social and province of Turin, and around 50 in Rubiera in the public policy import of cancers caused by work. -

Il Prefetto Della Provincia Di Torino Prot

Il Prefetto della provincia di Torino Prot. n. 91215/2019/Area III VISTA l’istanza presentata dal Sig. VEGNI Mauro, nato a Cetona (SI) il 7.2.1959, Responsabile Ciclismo della RCS Sport S.p.A., con sede a Milano in Via Rizzoli n. 8, affiliata alla F.C.I. – Federazione Ciclistica Italiana, intesa ad ottenere la temporanea sospensione della circolazione di veicoli estranei alla gara, persone ed animali con divieto di sosta e rimozione su entrambi i lati della carreggiata sui seguenti tratti stradali interessati dal passaggio della 13ª tappa “PINEROLO – CERESOLE REALE (LAGO SERRU’)” del “102° Giro d’Italia” indetta per il giorno venerdì 24 maggio 2019, con transito nel territorio della Città metropolitana di Torino, previsto tra le ore 11.30 e le ore 17.34, nei seguenti Comuni: Pinerolo, Roletto, Frossasco, Cumiana, Giaveno, Avigliana, Almese, Villar Dora, Rubiana, Viù, Germagnano, Traves, Lanzo Torinese, Balangero, Mathi, Villanova C.se, Grosso, Nole, Rocca Canavese, Barbania, Levone, Rivara, Busano, San Ponso, Valperga, Cuorgnè, Chiesanuova, Borgiallo, Colleretto Castelnuovo, Frassinetto, Pont Canavese, Sparone, Locana, Noasca, Ceresole Reale sul percorso illustrato nella cronotabella allegata al presente decreto per farne parte integrante (All. 1); ATTESO che, in ragione dell’importanza che la manifestazione riveste a livello internazionale, l’Ente Organizzatore ha richiesto la deroga alla temporanea sospensione della circolazione di veicoli estranei alla gara, persone ed animali fino al passaggio del “fine corsa” anche oltre i 15 minuti -

Strategia Valli Di Lanzo La Montagna Si Avvicina

strategia nazionale per le aree interne Strategia per le Valli di Lanzo Il passato recente e il futuro prossimo STRATEGIA NAZIONALE PER LE AREE INTERNE La realtà socioeconomica territoriale e le sue dinamiche evolvono rapidamente, spesso più rapidamente delle idee e delle strategie che ne sono a fondamento, sempre più velocemente della percezione che anche un osservatore aento riesce ad avere del mutamento stesso. Nel periodo intercorso tra l’approvazione della Bozza di Strategia 28 Seembre 2018) e la redazione della Strategia d’Area, di seguito presentata, il mondo nella sua globalit ha vissuto una delle fasi pi dramma'che registrate negli ul'mi decenni, ma nel contempo pi propulsive, pur nella preoccupante contabilizzazione di da' econometrici nega'vi e della ancor pi tragica registrazione dei decessi correla' alla pandemia di COVI, 19. Il territorio dell’Area Interna delle Valli di Lanzo non solo non . stato esente dal di/uso fenomeno epidemiologico e dalle rela've conseguenze dell’impao nega'vo subito dalle famiglie, dalle imprese, dal tessuto sociale nel suo complesso e ancor pi dal tessuto economico. Il territorio tuo ha registrato 0 forse si comincia ad averne contezza solo ora 0 nuove tendenze e mutamen' di ruoli, possibilit di azione e di abitudini pi marcate rispeo ad altre aree montane, in 1uanto la realt locale . streamente correlata con il tessuto ciadino di 2orino e di tua l’area metropolitana torinese. In tal senso, le Valli di Lanzo nella loro accezione pi ampia e il territorio della Ci 3etropolitana, sono da sempre caraerizza' da una forte correlazione con maggiori rappor' di biunivocit rispeo a 1uanto possa darne conto un primo sguardo4 pendolarismo per lavoro e studio, 5usso di merci da e verso le valli, fruizione turis'ca e fre1uentazione occasionale, seconde case e storicit di presenza, senso di appartenenza e di comunit . -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE INFORMAZIONI PERSONALI Nome BARBATO SUSANNA Data di nascita 05/12/1972 Qualifica Segretario comunale Amministrazione COMUNE DI CUORGNE’ Responsabile Segreteria comunale convenzionata tra i Comuni di Incarico attuale Cuorgnè 50% e il Comune di Nole 50% Numero telefonico dell’ufficio 0124655210 E-mail istituzionale [email protected] TITOLI DI STUDIO E PROFESSIONALI ED ESPERIENZE LAVORATIVE Titolo di studio Laurea in economia conseguita presso l'Università degli studi di Torino il 18.03.1996 Altri titoli di studio e Iscritta all’Albo Nazionale dei Segretari Comunali e Provinciali per il professionali superamento del corso – concorso per l’accesso in carriera della durata di 18 mesi (gennaio 2002 – luglio 2003) seguito da 6 mesi di tirocinio pratico, presso la Scuola Superiore della Pubblica Amministrazione Locale – Roma. Dicembre 2006: conseguimento dell’idoneità a segretario generale (Fascia B) superando il relativo corso di abilitazione presso la Scuola Superiore della Pubblica Amministrazione Locale – Roma. Esperienze professionali (incarichi ricoperti) 01.02.1997 – 23. 12.2003 Comune di Rivara Responsabile del Servizio Economico Finanziario (ex VII q.f.) 29.12.2003 – 31.05.2007 Segretario Comunale (Fascia C) in convenzione fra i Comuni di Rivara e Ceresole Reale 01.06.2007 – 31.08.2009 Segretario comunale (Fascia B) in convenzione tra i Comuni di Rivara, Ceresole Reale e Cintano 01.09.2009 – 30.06.2013 Segretario Comunale (Fascia B) in convenzione tra i Comuni di Rivara, San Giorgio Canavese e Candia Canavese -

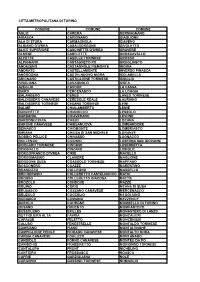

Città Metropolitana Di Torino Comune Comune Comune

CITTÀ METROPOLITANA DI TORINO COMUNE COMUNE COMUNE AGLIÈ CAREMA GERMAGNANO AIRASCA CARIGNANO GIAGLIONE ALA DI STURA CARMAGNOLA GIAVENO ALBIANO D'IVREA CASALBORGONE GIVOLETTO ALICE SUPERIORE CASCINETTE D'IVREA GRAVERE ALMESE CASELETTE GROSCAVALLO ALPETTE CASELLE TORINESE GROSSO ALPIGNANO CASTAGNETO PO GRUGLIASCO ANDEZENO CASTAGNOLE PIEMONTE INGRIA ANDRATE CASTELLAMONTE INVERSO PINASCA ANGROGNA CASTELNUOVO NIGRA ISOLABELLA ARIGNANO CASTIGLIONE TORINESE ISSIGLIO AVIGLIANA CAVAGNOLO IVREA AZEGLIO CAVOUR LA CASSA BAIRO CERCENASCO LA LOGGIA BALANGERO CERES LANZO TORINESE BALDISSERO CANAVESE CERESOLE REALE LAURIANO BALDISSERO TORINESE CESANA TORINESE LEINÌ BALME CHIALAMBERTO LEMIE BANCHETTE CHIANOCCO LESSOLO BARBANIA CHIAVERANO LEVONE BARDONECCHIA CHIERI LOCANA BARONE CANAVESE CHIESANUOVA LOMBARDORE BEINASCO CHIOMONTE LOMBRIASCO BIBIANA CHIUSA DI SAN MICHELE LORANZÈ BOBBIO PELLICE CHIVASSO LUGNACCO BOLLENGO CICONIO LUSERNA SAN GIOVANNI BORGARO TORINESE CINTANO LUSERNETTA BORGIALLO CINZANO LUSIGLIÈ BORGOFRANCO D'IVREA CIRIÈ MACELLO BORGOMASINO CLAVIERE MAGLIONE BORGONE SUSA COASSOLO TORINESE MAPPANO BOSCONERO COAZZE MARENTINO BRANDIZZO COLLEGNO MASSELLO BRICHERASIO COLLERETTO CASTELNUOVO MATHI BROSSO COLLERETTO GIACOSA MATTIE BROZOLO CONDOVE MAZZÈ BRUINO CORIO MEANA DI SUSA BRUSASCO COSSANO CANAVESE MERCENASCO BRUZOLO CUCEGLIO MEUGLIANO BURIASCO CUMIANA MEZZENILE BUROLO CUORGNÈ MOMBELLO DI TORINO BUSANO DRUENTO MOMPANTERO BUSSOLENO EXILLES MONASTERO DI LANZO BUTTIGLIERA ALTA FAVRIA MONCALIERI CAFASSE FELETTO MONCENISIO CALUSO FENESTRELLE MONTALDO -

Processo Verbale Adunanza Ix

PROCESSO VERBALE ADUNANZA IX DELIBERAZIONE DELLA CONFERENZA METROPOLITANA DI TORINO 19 giugno 2019 Presidenza: Chiara APPENDINO Il giorno 19 del mese di giugno duemiladiciannove, alle ore 15,00, in Torino, C.so Inghilterra 7, nella Sala “Auditorium” della Città Metropolitana di Torino, sotto la Presidenza della Sindaca Metropolitana Chiara APPENDINO e con la partecipazione della Segretaria Generale Daniela Natale si è riunita la Conferenza Metropolitana come dall’avviso del 31 maggio 2019 recapitato nel termine legale - insieme con l'Ordine del Giorno - ai singoli componenti della Conferenza Metropolitana e pubblicato all'Albo Pretorio on-line. Sono intervenuti i seguenti componenti la Conferenza Metropolitana: COMUNE RESIDENTI AGLIE’ SINDACO SUCCIO MARCO 2.644 AVIGLIANA SINDACO ARCHINA’ ANDREA 12.129 BARBANIA VICE SINDACO COSTANTINO MARIA 1.623 BEINASCO VICE SINDACO LUMETTA ELENA 18.104 BOLLENGO SINDACO RICCA LUIGI SERGIO 2.112 BORGONE SUSA VICE SINDACO ROLANDO ANDREA 2.320 BRICHERASIO VICE SINDACO MERLO ILARIO 4.517 BROZOLO VICE SINDACO BONGIOVANNI SERGIO 471 BRUINO VICE SINDACO VERDUCI ANELLO 8.479 BUTTIGLIERA ALTA VICE SINDACO SACCENTI LAURA 6.386 CAFASSE VICE SINDACO AIMAR SERGIO 3.511 CALUSO VICE SINDACO CHIARO LUCA 7.483 CAMBIANO SINDACO VERGNANO CARLO 6.215 CAMPIGLIONE FENILE VICE SINDACO RISSO MARIA 1.382 CANDIA CANAVESE VICE SINDACO LA MARRA UMBERTO 1.286 CANTOIRA VICE SINDACO OLIVETTI CELESTINA 554 CARMAGNOLA SINDACO GAVEGLIO IVANA 28.563 CASELETTE VICE SINDACO GIORGIO MOTRASSINO 2.931 CASELLE TORINESE SINDACO BARACCO LUCA -

Progetto Cirr Consiglio Intercomunale Delle Ragazze E Dei Ragazzi

! PROGETTO CIRR CONSIGLIO INTERCOMUNALE DELLE RAGAZZE E DEI RAGAZZI REGOLAMENTO ! GENERALITÀ Tra gli scopi degli enti locali, come sanciti dalla Costituzione e dalla legge di riforma delle autonomie locali, rientrano la promozione e lo sviluppo di forme associative che favoriscano la partecipazione dei cittadini di ogni età e condizione sociale alla vita amministrativa e, in particolare, un’idonea crescita socio-culturale dei giovani nella piena e naturale consapevolezza dei diritti e dei doveri civici verso le istituzioni affinché diventino cittadini consapevoli, responsabili e rispettosi delle regole di democrazia e di civile convivenza. In quest'ambito si propone l’attivazione del progetto "CONSIGLIO INTERCOMUNALE DELLE RAGAZZE E DEI RAGAZZI", indicato come CIRR, che coinvolgerà i Comuni di Brozolo, Brusasco, Cavagnolo, Lauriano, Monteu da Po, Verrua Savoia [con l’ulteriore aggiunta dei comuni di Casalborgone e San Sebastiano, qualora si concordasse di estendere il CIRR ai nuovi plessi dell’IC Brusasco: ci chiediamo se sia necessario lasciare questa “postilla” affinché la secondaria di primo grado di Casalborgone possa aderire al progetto.]. Il progetto intende coinvolgere gli alunni della Scuola Secondaria di primo grado. Il CIRR sarà eletto mediante regolari votazioni che si svolgeranno, secondo le indicazioni riportate nel presente regolamento allegato. А livello scolastico, il progetto sarà coordinato da un gruppo di insegnanti costituito dai referenti individuati tra il personale scolastico disponibile a seguire il progetto [per -

Orario Valido Dal 13 SETTEMBRE 2021

N2102c Orario valido dal 13 SETTEMBRE 2021 Direzione (Torino/Venaria) BORGARO GERMAGNANO CERES BUS SF2 BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS TORINO - VENARIA FERIALE SF2 FERIALE FERIALE SF2 SF2 SF2 SF2 FERIALE SF2 SF2 SF2 SF2 SF2 SCOLAST. SF2 SF2 SCOLAST. SF2 SF2 SF2 SF2 SF2 SF2 FERIALE SF2 SF2 FERIALE FERIALE BORGARO LUN -VEN LUN -SAB LUN -VEN LUN -SAB LUN -SAB LUN -SAB SOLO FEST. LUN -SAB SOLO FEST. SOLO FEST. LUN -SAB LUN -VEN LUN -SAB LUN -VEN SOLO FEST. LUN -SAB NO SAB LUN -SAB LUN -SAB NO SAB LUN -VEN LUN -SAB LUN -VEN LUN -VEN Torino Porta Susa p 5:30 6:06 6:45 7:00 6:36 7:06 7:36 8:06 9:35 9:36 10:36 11:06 12:06 13:06 13:45 13:36 14:06 14:45 14:36 15:06 15:36 16:06 17:06 17:36 17:45 18:06 19:06 20:35 23:05 TO -Mad. Campagna p 5:45 6:26 7:00 7:15 6:56 7:26 7:56 8:26 9:50 9:56 10:56 11:26 12:26 13:26 14:00 13:56 14:26 15:00 14:56 15:26 15:56 16:26 17:26 17:56 18:00 18:26 19:26 20:50 23:20 Venaria p 6:41 7:11 7:41 8:11 8:41 10:11 11:11 11:41 12:41 13:41 14:11 14:41 15:11 15:41 16:11 16:41 17:41 18:11 18:41 19:41 Borgaro a 6:53 7:23 7:53 8:23 8:53 10:23 11:23 11:53 12:53 13:53 14:23 14:53 15:23 15:53 16:23 16:53 17:53 18:23 18:53 19:53 SFMA 7 9 11 13 15 23 25 325 27 31 35 37 39 41 43 45 47 51 53 55 59 TRENO FERIALE FERIALE GIORNA FERIALE SOLO SOLO SOLO FERIALE FERIALE GIORNA GIORNA FERIALE FERIALE SOLO FERIALE FERIALE FERIALE FERIALE FERIALE FERIALE GIORNA LUN-SAB LUN-SAB LIERO LUN-SAB FESTIVI FESTIVI FESTIVI LUN-VEN -

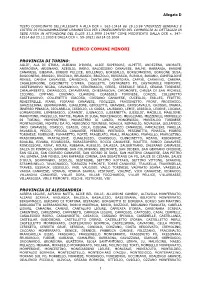

Elenco Comuni Minori

Allegato D TESTO COORDINATO DELL’ALLEGATO A ALLA DCR n. 563-13414 del 29.10.99 “INDIRIZZI GENERALI E CRITERI DI PROGRAMMAZIONE URBANISTICA PER L’INSEDIAMENTO DEL COMMERCIO AL DETTAGLIO IN SEDE FISSA IN ATTUAZIONE DEL D.LGS 31.3.1998 114/98” COME MODIFICATO DALLA DCR n. 347- 42514 del 23.12.2003 E DALLA DCR n. 59-10831 del 24.03.2006 ELENCO COMUNI MINORI PROVINCIA DI TORINO: AGLIE', ALA DI STURA, ALBIANO D'IVREA, ALICE SUPERIORE, ALPETTE, ANDEZENO, ANDRATE, ANGROGNA, ARIGNANO, AZEGLIO, BAIRO, BALDISSERO CANAVESE, BALME, BARBANIA, BARONE CANAVESE, BIBIANA, BOBBIO PELLICE, BOLLENGO, BORGIALLO, BORGOMASINO, BORGONE SUSA, BOSCONERO, BROSSO, BROZOLO, BRUSASCO, BRUZOLO, BURIASCO, BUROLO, BUSANO, CAMPIGLIONE FENILE, CANDIA CANAVESE, CANISCHIO, CANTALUPA, CANTOIRA, CAPRIE, CARAVINO, CAREMA, CASALBORGONE, CASCINETTE D'IVREA, CASELETTE, CASTAGNETO PO, CASTAGNOLE PIEMONTE, CASTELNUOVO NIGRA, CAVAGNOLO, CERCENASCO, CERES, CERESOLE REALE, CESANA TORINESE, CHIALAMBERTO, CHIANOCCO, CHIAVERANO, CHIESANUOVA, CHIOMONTE, CHIUSA DI SAN MICHELE, CICONIO, CINTANO, CINZANO, CLAVIERE, COASSOLO TORINESE, COAZZE, COLLERETTO CASTELNUOVO, COLLERETTO GIACOSA, COSSANO CANAVESE, CUCEGLIO, EXILLES, FELETTO, FENESTRELLE, FIANO, FIORANO CANAVESE, FOGLIZZO, FRASSINETTO, FRONT, FROSSASCO, GARZIGLIANA, GERMAGNANO, GIAGLIONE, GIVOLETTO, GRAVERE, GROSCAVALLO, GROSSO, INGRIA, INVERSO PINASCA, ISOLABELLA, ISSIGLIO, LA CASSA, LAURIANO, LEMIE, LESSOLO, LEVONE, LOCANA, LOMBARDORE, LOMBRIASCO, LORANZE', LUGNACCO, LUSERNETTA, LUSIGLIE', MACELLO, MAGLIONE, MARENTINO, MASSELLO, MATTIE,