Language and Minority in the Making of Modern Thailand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AN BEM 58 4C EN.Indd

CORPORATE SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ACTIVITIES The Company, as the expressway and metro service provider, is committed to helping alleviate traffic problems in Bangkok and its surrounding provinces, through the fully-integrated mass rapid transit and transportation systems in order to upgrade the quality of life and shape the future of Thailand’s transportation system. Furthermore, the Company operates its businesses based on the good corporate governance, and is socially responsible in both expressway and metro businesses. The Social Activities of Expressway Business Good Family Relationships “Moms & Kids Strengthen Relationships at Art and Craft Communities in Ratchaburi” On the occasion of National Mother’s Day, as a special family day, in which the Company played a part in strengthening family relationships by inviting the expressway users and their families to visit the “City… You Can’t Miss”, Ratchaburi Province, known as a cultural city on the Mae Klong basin, with a long history, multi-cultural arts and traditions that coexist harmoniously. Moreover, the families participated in the “Me & Mom Made” activity in which dads, moms, and kids jointly arranged flowers for offering to the Buddhist monks in a loving and warm atmosphere for all families. “Expressway Invites Dads & Kids to Strengthen Relationships with Natural Learning in Burgbanburi” On the occasion of National Father’s Day, whereby the Company organized this activity to strengthen the family relationships to enhance their love bonds, in Burgbanburi, as a natural learning source in Nakhon Ratchasima Province, by inviting the expressway users and their families to closely learn about nature and find happiness from frugal lifestyle with minimum use of energy and chemicals to save the world sustainably. -

กองทุนรวมอสังหาริมทรัพย์เคพีเอ็น KPN Property Fund (KPNPF)

กองทุนรวมอสังหาริมทรัพย์เคพีเอ็น KPN Property Fund (KPNPF) วันจันทร์ที่ 1 เมษายน 2562 เวลา 14.00 น. – 16.00 น. ณ ห้อง แลนด์มาร์ค บอลรูม โรงแรมเดอะแลนด์มาร์ค กรุงเทพฯ Invitation Letter to the Annual General Meeting of Unitholders of the year 2019 Monday, 1 April 2019, from 2.00 p.m. – 4.00 p.m. at Landmark Ballroom, The Landmark Bangkok Hotel 22 March 2019 Subject: Invitation to the Annual General Meeting of Unitholders of KPN Property Fund (KPNPF) of the year 2019 Attention: The Unitholders of KPN Property Fund (KPNPF) Enclosures: 1. Annual Report for the Year 2018 in the form of compact disk (or download at the website http://www.kasikornasset.com) 2. Procedures for Registration, Attendance of the Meeting and Grant of proxy 3. Proxy forms 4. Profile of the Fund Manager to be a proxy 5. Map of the meeting venue Kasikorn Asset Management Company Limited (the “Management Company”), on behalf of the Management Company of KPN Property Fund (KPNPF) (the “Property Fund”) deemed it appropriate to convene the Annual General Meeting of Unitholders of the year 2019 on 1 April 2019, from 2 p.m. to 4 p.m. (registration starting at 1 p.m.), at the Landmark Ballroom, 7th floor, the Landmark Bangkok Hotel, located at 138 Sukhumvit Road, Khlong Toei Sub-District, Khlong Toei District, Bangkok 10110. At the Annual General Meeting of Unitholders of the year 2019, the unitholders and the proxy shall attend the meeting not less than 25 (twenty five) unitholders, or not less than half of the total numbers of the unitholders who hold an aggregate amount of not less than one third of the total unit sold, thereby constituting a quorum of the Annual General Meeting of Unitholders. -

June 4, 2021 Thai Enquirer Summary Covid-19 News • the Ministry Of

June 4, 2021 Thai Enquirer Summary Covid-19 News The Ministry of Public Health has come out to say that by Monday June 7th there will be vaccines distributed as per the promise. The aim is to have 2 million doses by June 15th but it will be a combination of AstraZeneca and SinVac. Total of 6 million doses will be available during the month of June as promised but it will be a combination of both these 2 (AstraZeneca and SinoVac). This is a long shot from the 6-million doses in the month of JUNE alone, that were supposed to be coming out from Siam BioScience’s plant in Thailand. From July until December 2021 each month Siam BioScience, that is owned by the Royal family of Thailand, was to deliver 10 million doses a month. As the country faces shortage of vaccines, the planned vaccination across the country are now being delayed ‘indefinitely’. Below are the provinces around Thailand where the hospitals have come out to say that they will delay the vaccination process. Chiang Mai Bangkok Hospital Chiang Mai has said that all those who registered for the vaccine, the distribution has been delayed further notice. Other hospitals such as Sanpatong Hospital, has also said the same thing. Chiang Mai Ram Hospital also said the same thing of delays therefore vaccination process needs to be delayed. McCormick Hospital also said the same thing. o Below are some of the announcements by the hospitals in Chiang Mai Bangkok Hospital Chiangmai McCormick Hospital Chiang Mai Ram Hospital Lampang – The province that was showcased as the Lampang Model for registration also is witnessing a delay in delivery of the vaccines. -

SDN Changes 2005

OFFICE OF FOREIGN ASSETS CONTROL CHANGES TO LIST OF SPECIALLY DESIGNATED NATIONALS AND BLOCKED PERSONS SINCE JANUARY 1, 2005 This publication of Treasury's Office of EMPENO RIO TIJUANA, S.A. DE C.V., Tijuana, 1966; POB Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico Foreign Assets Control ("OFAC") is designed Baja California, Mexico; c/o MULTISERVICIOS (individual) [SDNTK] as a reference tool providing actual notice of DEL NOROESTE DE MEXICO, S.A. DE C.V., ESCOBEDO MORALES, Sandra Angelica, c/o actions by OFAC with respect to Specially Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico; DOB 17 Sep CENTRO CAMBIARIO KINO, S.A. DE C.V., Designated Nationals and other entities whose 1954; POB Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico; Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico; c/o property is blocked, to assist the public in R.F.C. BERM-540917-181 (Mexico) (individual) CONSULTORIA DE INTERDIVISAS, S.A. DE complying with the various sanctions [SDNTK] C.V., Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico; c/o programs administered by OFAC. The latest BRAVIO ARMORED GROUP (a.k.a. MULTISERVICIOS ALPHA, S.A. DE C.V., changes may appear here prior to their MULTISERVICIOS BRAVIO, S.A. DE C.V.), Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico; DOB 25 Dec publication in the Federal Register, and it is Local C-25 Plaza Rio, Colonia Zona Rio, Tijuana, 1966; POB Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico intended that users rely on changes indicated Baja California, Mexico; Av. Via Rapida 26, (individual) [SDNTK] in this document that post-date the most Colonia Zona Rio, Tijuana, Baja California, GAMAL-MULTISERVICIOS (a.k.a. CENTRO recent Federal Register publication with Mexico; R.F.C. -

Post-Evaluation Report for Oecf Loan Projects 1998

Country :Kingdom of Thailand Project :Bangkok Water Supply Improvement Project (1)Tunnel Rehabilitation, (2)Stage II- Phase 1B Borrower :Metropolitan Waterworks Authority (MWA) Executing Agency :Metropolitan Waterworks Authority (MWA) Date of Loan Agreement :(1)November 1988, (2)November 1988 Loan Amount :(1)¥2,985 million, (2)¥4,380 million Local Currency :Baht Report Date :March 1998 (Field Survey: October 1997) Sam Lae Raw Water Pump Station -253- [Reference] 1.Terminology ① Classification of water conveyance, water distribution, and water supply Water conveyance indicates the transport of clean water produced at water treatment plants to water distribution facilities that are relay points. The facilities employed for this purpose (pumps, etc.) are called water conveyance facilities, and the water pipes used to convey the water are called service pipe lines. Water distribution refers to the distribution of water from relay points to end-users. The facilities employed for this purpose are called water distribution facilities, and the water pipes used to convey the water are called distributing pipes. The water pipes that link distributing pipes to water faucets are called water supply pipes, and water supply pipes and water faucets are collectively referred as water-service installations. Normally, water-service installations are owned by the end-user. ② Steel lining method In order to prevent water loss, lining, which consists of laying the inside of already laid pipes with steel plates, concrete, resin, etc., is used. In the case of steel lining, steel plates are used. Grout is injected to fill gaps between the lining and the pipes. ③ Pipe insertion method In order to prevent water loss, new pipes with a diameter equal to or smaller than that of existing pipes are inserted. -

EN Cover AR TCRB 2018 OL

Vision and Mission The Thai Credit Retail Bank Public Company Limited Vision Thai Credit is passionate about growing our customer’s business and improving customer’s life by providing unique and innovative micro financial services Mission Be the best financial service provider to our micro segment customers nationwide Help building knowledge and discipline in “Financial Literacy” to all our customers Create a passionate organisation that is proud of what we do Create shareholders’ value and respect stakeholders’ interest Core Value T C R B L I Team Spirit Credibility Result Oriented Best Service Leadership Integrity The Thai Credit Retail Bank Public Company Limited 2 Financial Highlight Loans Non-Performing Loans (Million Baht) (Million Baht) 50,000 3,000 102% 99% 94% 40,000 93% 2,000 44,770 94% 2,552 2,142 2018 2018 2017 30,000 39,498 Consolidated The Bank 1,000 34,284 1,514 20,000 Financial Position (Million Baht) 1,028 27,834 Total Assets 50,034 50,130 45,230 826 23,051 500 Loans 44,770 44,770 39,498 10,000 Allowance for Doubtful Accounts 2,379 2,379 1,983 - - Non-Performing Loans (Net NPLs) 1,218 1,218 979 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Non-Performing Loans (Gross NPLs) 2,552 2,552 2,142 LLR / NPLs (%) Liabilities 43,757 43,853 39,728 Deposits 42,037 42,133 37,877 Total Capital Fund to Risk Assets Net Interest Margin (NIMs) Equity 6,277 6,277 5,502 Statement of Profit and Loss (Million Baht) 20% 10% Interest Income 4,951 4,951 3,952 16.42% 15.87% Interest Expenses 901 901 806 15.13% 8% 13.78% 15% 13.80% Net Interest -

Bangkok's Street Vending Ban: a Summary of the Research on the Social and Economic Impacts

WIEGO Resource Document No 12 WIEGO Resource Document No. 12 September 2019 Bangkok’s Street Vending Ban: A Summary of the Research on the Social and Economic Impacts By Kannika Angsuthonsombat, with Chidchanok Samantrakulu WIEGO Resource Document No 12 WIEGO Resource Documents WIEGO Resource Documents include WIEGO generated literature reviews, annotated bibliographies, and papers reflecting the findings from new empirical work. They provide detail to support advocacy, policy or research on specific issues. Publication date: September 2019 ISBN number: 978-92-95106-37-6 Please cite this publication as: Angsuthonsombat, Kannika. 2019. Bangkok’s Street Vending Ban: A Summary of the Research on the Social and Economic Impacts. WIEGO Resource Document 12. Manchester, UK: WIEGO Published by Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO) A Charitable Company Limited by Guarantee – Company No. 6273538, Registered Charity No. 1143510 WIEGO Limited 521 Royal Exchange Manchester, M2 7EN United Kingdom www.wiego.org Translator (Thai to English): Chutimas Suksai Series editor: Caroline Skinner Copy editor and layout: Megan Macleod Cover photograph by: Pailin Wedel Copyright © WIEGO. This report can be replicated for educational, organizing and policy purposes as long as the source is acknowledged. WIEGO Resource Document No 12 Table of Contents Introduction ...............................................................................................................................1 Street Vendor Categories, Challenges and Characteristics -

Case Study of Klong Chan Flat, Bangkok

Analysis of Community Safety Conditions of an Old Public Housing Project: Case Study of Klong Chan Flat, Bangkok Tanaphoom Wongbumru1, * and Bart Dewancker2 1 Faculty of Architecture, Rajamangala University of Technology Thanyaburi, Pathumthani 12110, Thailand 2 Faculty of Environmental Engineering, The University of Kitakyushu, Fukuoka 808-0135, Japan Abstract Safety, in regards of all aspects, is considered a major priority to community. The residents perceived their safety through physical surroundings of living places. Accordingly, a long-established, old public housing community with open access, Klong Chan Flat, was chosen to be examined regarding safety issues through field survey and questionnaire. The results showed Klong Chan Flat is divided into three scale of safety-concerned areas; dwellings (installed with window and door grilles), buildings (provided with CCTV, lighting, and motorcycle docking), and community (stationed with a police check-point). The overall satisfaction towards community safety of residents staying in buildings with fully provided CCTV, lighting, motorcycle docking, and unsafe community area resulted in a significant relationship of these variables at .05. The motorcycle docking and lighting are found to be an important element of building safety with its high correlation value at .631 and .507 respectively. In addition, five significant spots evidenced with high criminal incidents were identified through an interview from residents and police information. Consequently, more surveillance must be acted upon and focused on physical conditions as well as building maintenance and management. These results conferred a baseline data of initial investigation of old public housing project towards safety issues. Thus, these significant factors are to be determined in terms of safety management to enhance standard and quality of living of the * Corresponding author. -

MICE Destinations

Background... The Guidebook of creative ideas for MICE destinations Thailand Convention and Exhibition Bureau (Public Organization) or TCEB has implemented the projects in developing MICE destinations and making of MICE activities planning guidebook “Thailand 7 MICE Magnificent Themes “ with the purpose to develop venues for MICE activities or new MICE destination for entrepreneurs and MICE industry that can be practically used. This guidebook of creative idea for MICE destinations will mainly focus on the five MICE cities including Bangkok, Khon Kaen, Chiang Mai, Pattaya and Phuket, which will be presented through seven perspectives, namely Fascinating History and Culture, Exhilarating Adventures, Treasured Team Building, CSR and Green Meetings, Beach Bliss, Lavish Luxury, Culinary Journeys TCEB truly hopes that this guidebook “Creative ideas for MICE destinations” will provide alternative, explore new perspectives in creating memorable experience for all of your MICE events and meetings. Thailand 7 MICE 6 Magnificent Themes 8 BANGKOK 26 KHONKEAN 42 CHIANGMAI 60 PATTAYA 84 PHUKET information of convention 98 venues / hotels / restaurants Thailand 7 MICE Magnificent Themes Fascinating History and Culture means historic, cultural, and social – value site visit including places of mental affinity for later generations. Exhilarating Adventures refer to travelling to places where the environment is different from normal environment, consisting of physical activity, natural environment, and immersion into culture. Treasured Team Building illustrates harmony creation among members of a group through various activities which may be a brainstorming activity or joining activity bases so that groups can share ideas and exchange knowledge. CSR and Green Meetings means Corporate Social Responsibility which is a commitment to the stakeholders in order to operate the business in a transparent and ethically sustainable manner, either in economic, society and environment. -

Guidebook for International Residents in Bangkok

1ST EDITION AUGUST 2019 GUIDEBOOK FOR INTERNATIONAL RESIDENTS IN BANGKOK International AffairS Office, Bangkok Metropolitan Administration GREETING Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA) is the local organization which is directly responsible for city administration and for looking after the well-being of Bangkok residents. Presently, there are a great number of foreigners living in Bangkok according to the housing census 2010, there are 706,080 international residents in Bangkok which is accounted If you have any feedback/questions for 9.3% of all the Thai citizen in Bangkok. regarding this guidebook, please Moreover, information from Foreign contact International Affairs Office, Workers Administration Office shows that Bangkok Metropolitan Administration there are 457,700 foreign migrant workers (BMA) in Bangkok. Thus, we are pleased to make at email: a Guidebook for International Residents in [email protected] Bangkok. This guidebook composes of public services provided by the BMA. We and Facebook: do hope that this guidebook will make https://www.facebook.com/bangkokiad/ your life in Bangkok more convenient. International Affairs Office, Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA) PAGE 1 Photo by Berm IAO CONTENTS 0 1 G R E E T I N G P A G E 0 1 0 2 C I V I L R E G I S T R A T I O N ( M O V I N G - I N / N O N - T H A I I D C A R D ) P A G E 0 3 0 3 E M E R G E N C Y N U M B E R S P A G E 1 5 0 4 B A N G K O K M E T R O P O L I T A N A D M I N I S T R A T I O N A F F I L I A T E D H O S P I T A L S P A G E 1 9 0 5 U S E F U L W E B S I T E S P A G E 3 8 0 6 R E F E R E N C E P A G E 4 0 PAGE 2 Photo by Peter Hershey on Unsplash CIVIL REGISTRATION (Moving - In/ Non-Thai ID card) PAGE 3 Photo by Tan Kaninthanond on Unsplash Moving - In Any Non - Thai national who falls into one of these categories MUST register him/herself into Civil Registration database. -

Nomura Real Estate Takes Its First Step Into Bangkok's Housing Sales

To members of the press August 24, 2017 Nomura Real Estate Development Co., Ltd. Three Projects with over 2,000 Residential units Nomura Real Estate Takes its First Step into Bangkok’s Housing Sales Market Nomura Real Estate Development Co., Ltd. (head office: Shinjuku Ward, Tokyo; President and Representative Director: Seiichi Miyajima; hereinafter “Nomura”) announces that it has decided to participate in three condominium housing projects in Bangkok, Thailand, in partnership with a local Thai developer, Origin Property Public Company Ltd. (hereinafter “Origin”). These projects will represent Nomura’s first involvement in Housing projects in Bangkok. The three projects will be located in Ratchayothin (Chatuchak District), Onnut (Phra Khanong District) and Ramkhamhaeng (Bang Kapi District), all of which are near central Bangkok. The three locations will be extremely convenient, being within a ten-minute walk to existing or new stations of the BTS (elevated railway) and MRT (subway). The total number of residences to be provided by the three projects will exceed 2,000 units. The Nomura Real Estate Group has positioned overseas business as a growth field in its medium-term business plan (effective until March 2025). Accordingly, it plans to invest approximately 300 billion yen in residential projects and commercial projects by the business term ending in March 2025, the majority of which will target Asian countries where real estate demand is growing. Thus far, Nomura has agreed to participate in development projects in Shenyang, China; Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam; and Manila, the Philippines. It will now proceed with development projects in collaboration with a local partner that is enjoying phenomenal growth in Bangkok, Thailand, and looks to utilize its store of know-how in helping achieve “connect today with tomorrow`s possibilities” in Asian nations that are expected to see continuing growth. -

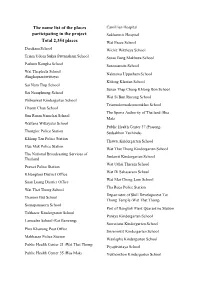

The Name List of the Places Participating in the Project

The name list of the places Camillian Hospital participating in the project: Sukhumvit Hospital Total 2,354 places Wat Pasee School Darakam School Wichit Witthaya School Triam Udom Suksa Pattanakarn School Surao Bang Makhuea School Pathum Kongka School Suraosam-in School Wat Thepleela School Naknawa Uppatham School (Singhaprasitwittaya) Khlong Klantan School Sai Nam Thip School Surao Thap Chang Khlong Bon School Sai Namphueng School Wat Si Bun Rueang School Phibunwet Kindergarten School Triamudomsuksanomklao School Chaem Chan School The Sports Authority of Thailand (Hua Sun Ruam Namchai School Mak) Wattana Wittayalai School Public Health Center 37 (Prasong- Thonglor Police Station Sudsakhon Tuchinda) Khlong Tan Police Station Thawsi Kindergarten School Hua Mak Police Station Wat That Thong Kindergarten School The National Broadcasting Services of Jindawit Kindergarten School Thailand Wat Uthai Tharam School Prawet Police Station Wat Di Sahasaram School Khlongtoei District Office Wat Mai Chong Lom School Suan Luang District Office Tha Ruea Police Station Wat That Thong School Department of Skill Development Tat Thanom But School Thong Temple (Wat That Thong) Somapanusorn School Port of Bangkok Plant Quarantine Station Tubkaew Kindergraten School Panaya Kindergarten School Lamsalee School (Rat Bamrung) Suwattana Kindergarten School Phra Khanong Post Office Srisermwit Kindergarten School Makkasan Police Station Wanlapha Kindergarten School Public Health Center 21 (Wat That Thong) Piyajitvittaya School Public Health Center 35 (Hua Mak) Yukhonthon