Assessing the Fidelity of the Fossil Record by Using Marine Bivalves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zebra & Quagga Mussels: Species Guide

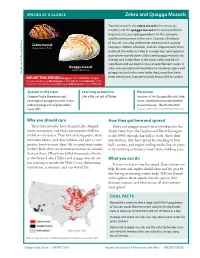

SPECIES IN DEPTH Zebra and Quagga Mussels NATIVE AND INVASIVE RANGE Zebra mussels are native to the Caspian and Black Seas (Eurasia); quagga mussels are native to the Dneiper River drainage in Ukraine. Both mussels have invaded freshwater systems of the United Kingdom, Western Europe, Canada, and the United States. In the United States, zebra mussels were established in the Great Lakes by 1986; quagga mussels were discovered in the Erie Canal and Lake Ontario in 1991. Now, zebra mussels are widespread in the Great Lakes and all Randy Westbrooks the major river drainages east of the Rocky Mountains. Zebra Mussel Quagga mussels are mostly confined to the lower Great Dreissena polymorpha Lakes area and seem to be replacing zebra mussels where their populations overlap. The zebra mussel is a West Coast distribution freshwater bivalve that, true to its name, is often Quagga and zebra mussels have breached the striped with dark bands Rockies and invaded Western states. Quagga mussels like a zebra, but it can were discovered in Lake Mead (Arizona) in 2007, and Fred Snyder Fred also be pure black or within months their shells were washing up on the unpigmented. This small mussel (about 3 cm shores of Lake Mohave (borders Arizona, California, long) is can be recognized from other mussels by and Nevada), and Lake Havasu (borders California and its triangular shape and one flat edge where its Arizona). From there, the mussels were transported byssal threads (for attaching to hard surfaces; see into many Southern California reservoirs via infested inset photo) emerge. However, it is not as easily Colorado River water that runs through aqueducts distinguished from quagga mussels, as both to the reservoirs, providing the region with half of its have byssal threads, which is a key feature for drinking water. -

CHAPTER 10 MOLLUSCS 10.1 a Significant Space A

PART file:///C:/DOCUME~1/ROBERT~1/Desktop/Z1010F~1/FINALS~1.HTM CHAPTER 10 MOLLUSCS 10.1 A Significant Space A. Evolved a fluid-filled space within the mesoderm, the coelom B. Efficient hydrostatic skeleton; room for networks of blood vessels, the alimentary canal, and associated organs. 10.2 Characteristics A. Phylum Mollusca 1. Contains nearly 75,000 living species and 35,000 fossil species. 2. They have a soft body. 3. They include chitons, tooth shells, snails, slugs, nudibranchs, sea butterflies, clams, mussels, oysters, squids, octopuses and nautiluses (Figure 10.1A-E). 4. Some may weigh 450 kg and some grow to 18 m long, but 80% are under 5 centimeters in size. 5. Shell collecting is a popular pastime. 6. Classes: Gastropoda (snails…), Bivalvia (clams, oysters…), Polyplacophora (chitons), Cephalopoda (squids, nautiluses, octopuses), Monoplacophora, Scaphopoda, Caudofoveata, and Solenogastres. B. Ecological Relationships 1. Molluscs are found from the tropics to the polar seas. 2. Most live in the sea as bottom feeders, burrowers, borers, grazers, carnivores, predators and filter feeders. 1. Fossil evidence indicates molluscs evolved in the sea; most have remained marine. 2. Some bivalves and gastropods moved to brackish and fresh water. 3. Only snails (gastropods) have successfully invaded the land; they are limited to moist, sheltered habitats with calcium in the soil. C. Economic Importance 1. Culturing of pearls and pearl buttons is an important industry. 2. Burrowing shipworms destroy wooden ships and wharves. 3. Snails and slugs are garden pests; some snails are intermediate hosts for parasites. D. Position in Animal Kingdom (see Inset, page 172) E. -

Dreisseina Spp

Dreissena spp. Diagnostic features Shells equivalve, mytiliform, inflated, sunken elongate internal ligament. There is a distinct septum behind umbos. Periostracum present. Edentate hinge without teeth. Pallial line not sinuate. Anatomy: eulamellibranch gills, closed mantle with two well developed short siphons. Very small foot with a byssal apparatus (Huber 2010). Dreissena polymorpha (length up to about 50 mm) Classification Class Bivalvia I nfraclass Heteroconchia Cohort Heterodonta Megaorder Neoheterodontei Order Myida Superfamily Dreissenoidea Family Dreissenidae Genus Dreissena van Beneden, 1835 (Type species: Mytilus polymorphus Pallas, 1771) (Synonyms - see http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=181565). Original reference: Van Beneden, P. J. (1835). Histoire naturelle et anatomique du Driessena [sic] polymorpha, genre nouveau dans la famille de mylilacées [sic]. Bulletins de L’ Academie Royale des Sciences et Belles-lettres de Bruxelles 2: 25-26 Type locality: Tributary of the Ural River in the Caspian Sea Basin, Russia. Biology and ecology Epifaunal. Very adaptable and can tolerate a wide range of salinity and water conditions, ranging from fresh to brackish water. Dioecious with external fertilisation and planktotrophic larvae. Extremely fertile and fast growing and can reach huge population densities. Distribution Native to the lakes of southeast Russia, the Dnieper River drainage of Ukraine and the Black and Caspian Seas. has also been introduced throughout Europe and North America, China and ndia. Notes Dresseina spp.do not occur in Australia but because it could be accidentally introduced, it is mentioned here as a potential threat. Two members of this genus have become major pests in freshwater environments in North America and Europe by clogging water intake structures (e.g., pipes and screens). -

Risk Assessment for Three Dreissenid Mussels (Dreissena Polymorpha, Dreissena Rostriformis Bugensis, and Mytilopsis Leucophaeata) in Canadian Freshwater Ecosystems

C S A S S C C S Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Secrétariat canadien de consultation scientifique Research Document 2012/174 Document de recherche 2012/174 National Capital Region Région de la capitale nationale Risk Assessment for Three Dreissenid Évaluation des risques posés par trois Mussels (Dreissena polymorpha, espèces de moules dreissénidées Dreissena rostriformis bugensis, and (Dreissena polymorpha, Dreissena Mytilopsis leucophaeata) in Canadian rostriformis bugensis et Mytilopsis Freshwater Ecosystems leucophaeata) dans les écosystèmes d'eau douce au Canada Thomas W. Therriault1, Andrea M. Weise2, Scott N. Higgins3, Yinuo Guo1*, and Johannie Duhaime4 Fisheries & Oceans Canada 1Pacific Biological Station 3190 Hammond Bay Road, Nanaimo, BC V9T 6N7 2Institut Maurice-Lamontagne 850 route de la Mer, Mont-Joli, QC G5H 3Z48 3Freshwater Institute 501 University Drive, Winnipeg, MB R3T 2N6 4Great Lakes Laboratory for Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 867 Lakeshore Road, PO Box 5050, Burlington, Ontario L7R 4A6 * YMCA Youth Intern This series documents the scientific basis for the La présente série documente les fondements evaluation of aquatic resources and ecosystems in scientifiques des évaluations des ressources et des Canada. As such, it addresses the issues of the écosystèmes aquatiques du Canada. Elle traite des day in the time frames required and the problèmes courants selon les échéanciers dictés. documents it contains are not intended as Les documents qu‟elle contient ne doivent pas être definitive statements on the subjects addressed considérés comme des énoncés définitifs sur les but rather as progress reports on ongoing sujets traités, mais plutôt comme des rapports investigations. d‟étape sur les études en cours. Research documents are produced in the official Les documents de recherche sont publiés dans la language in which they are provided to the langue officielle utilisée dans le manuscrit envoyé au Secretariat. -

Marine Boring Bivalve Mollusks from Isla Margarita, Venezuela

ISSN 0738-9388 247 Volume: 49 THE FESTIVUS ISSUE 3 Marine boring bivalve mollusks from Isla Margarita, Venezuela Marcel Velásquez 1 1 Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Sorbonne Universites, 43 Rue Cuvier, F-75231 Paris, France; [email protected] Paul Valentich-Scott 2 2 Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, Santa Barbara, California, 93105, USA; [email protected] Juan Carlos Capelo 3 3 Estación de Investigaciones Marinas de Margarita. Fundación La Salle de Ciencias Naturales. Apartado 144 Porlama,. Isla de Margarita, Venezuela. ABSTRACT Marine endolithic and wood-boring bivalve mollusks living in rocks, corals, wood, and shells were surveyed on the Caribbean coast of Venezuela at Isla Margarita between 2004 and 2008. These surveys were supplemented with boring mollusk data from malacological collections in Venezuelan museums. A total of 571 individuals, corresponding to 3 orders, 4 families, 15 genera, and 20 species were identified and analyzed. The species with the widest distribution were: Leiosolenus aristatus which was found in 14 of the 24 localities, followed by Leiosolenus bisulcatus and Choristodon robustus, found in eight and six localities, respectively. The remaining species had low densities in the region, being collected in only one to four of the localities sampled. The total number of species reported here represents 68% of the boring mollusks that have been documented in Venezuelan coastal waters. This study represents the first work focused exclusively on the examination of the cryptofaunal mollusks of Isla Margarita, Venezuela. KEY WORDS Shipworms, cryptofauna, Teredinidae, Pholadidae, Gastrochaenidae, Mytilidae, Petricolidae, Margarita Island, Isla Margarita Venezuela, boring bivalves, endolithic. INTRODUCTION The lithophagans (Mytilidae) are among the Bivalve mollusks from a range of families have more recognized boring mollusks. -

Microsatellite Loci for Dreissenid Mussels (Mollusca: Bivalvia: Dreissenidae) and Relatives: Markers for Assessing Exotic and Native Populations

Molecular Ecology Resources (2011) doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2011.03012.x Microsatellite loci for dreissenid mussels (Mollusca: Bivalvia: Dreissenidae) and relatives: markers for assessing exotic and native populations KEVIN A. FELDHEIM*, JOSHUA E. BROWN†‡, DOUGLAS J. MURPHY† and CAROL A. STEPIEN† *Field Museum, 1400 S. Lake Shore Dr., Chicago, IL 60605, USA, †Lake Erie Research Center and the Department of Environmental Sciences, The University of Toledo, 6200 Bayshore Road, Toledo, OH 43616, USA Abstract We developed and tested 14 new polymorphic microsatellite loci for dreissenid mussels, including the two species that have invaded many freshwater habitats in Eurasia and North America, where they cause serious industrial fouling damage and ecological alterations. These new loci will aid our understanding of their genetic patterns in invasive populations as well as throughout their native Ponto-Caspian distributions. Eight new loci for the zebra mussel Dreissena polymorpha polymorpha and six for the quagga mussel D. rostriformis bugensis were compared with new results from six previously published loci to generate a robust molecular toolkit for dreissenid mussels and their relatives. Taxa tested include D. p. polymorpha, D.r.bugensis,D.r.grimmi, D. presbensis, the ‘living fossil’ Congeria kusceri, and the dark false mussel Mytilopsis leucophaeata (the latter also is invasive). Overall, most of the 24 zebra mussel (N = 583) and 13 quagga mussel (N = 269) population samples conformed to Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium expectations for the new loci following sequen- tial Bonferroni correction. The 11 loci (eight new, three previously published) evaluated for D. p. polymorpha averaged 35.1 alleles and 0.72 mean observed heterozygosity per locus, and 25.3 and 0.75 for the nine loci (six new, three previously published) developed for D. -

Biological Synopsis of Dark Falsemussel (Mytilopsis Leucophaeata)

Biological Synopsis of Dark Falsemussel (Mytilopsis leucophaeata) J. Duhaime and B. Cudmore Fisheries and Oceans Canada Centre of Expertise for Aquatic Risk Assessment 867 Lakeshore Rd., P.O. Box 5050 Burlington, Ontario L7R 4A6 2012 Canadian Manuscript Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2980 Canadian Manuscript Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences Manuscript reports contain scientific and technical information that contributes to existing knowledge but which deals with national or regional problems. Distribution is restricted to institutions or individuals located in particular regions of Canada. However, no restriction is placed on subject matter, and the series reflects the broad interests and policies of Fisheries and Oceans Canada, namely, fisheries and aquatic sciences. Manuscript reports may be cited as full publications. The correct citation appears above the abstract of each report. Each report is abstracted in the data base Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Abstracts. Manuscript reports are produced regionally but are numbered nationally. Requests for individual reports will be filled by the issuing establishment listed on the front cover and title page. Numbers 1-900 in this series were issued as Manuscript Reports (Biological Series) of the Biological Board of Canada, and subsequent to 1937 when the name of the Board was changed by Act of Parliament, as Manuscript Reports (Biological Series) of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. Numbers 1426 - 1550 were issued as Department of Fisheries and Environment, Fisheries and Marine Service Manuscript Reports. The current series name was changed with report number 1551. Rapport Manuscrit Canadien des Sciences Halieutiques et Aquatiques Les rapports manuscrits contiennent des renseignements scientifiques et techniques qui constituent une contribution aux connaissances actuelles, mais qui traitent de problèmes nationaux ou régionaux. -

Zebra and Quagga Mussels

SPECIES AT A GLANCE Zebra and Quagga Mussels Two tiny mussels, the zebra mussel (Dreissena poly- morpha) and the quagga mussel (Dreissena rostriformis bugensis), are causing big problems for the economy and the environment in the west. Colonies of millions of mussels can clog underwater infrastructure, costing Zebra mussel (Actual size is 1.5 cm) taxpayers millions of dollars, and can strip nutrients from nearly all the water in a lake in a single day, turning entire ecosystems upside down. Zebra and quagga mussels are already well established in the Great Lakes and Missis- sippi Basin and are beginning to invade Western states. It Quagga mussel takes only one contaminated boat to introduce zebra and (Actual size is 2 cm) quagga mussels into a new watershed; once they have Amy Benson, U.S. Geological Survey Geological Benson, U.S. Amy been introduced, they are virtually impossible to control. REPORT THIS SPECIES! Oregon: 1-866-INVADER or Oregon InvasivesHotline.org; Washington: 1-888-WDFW-AIS; California: 1-916- 651-8797 or email [email protected]; Other states: 1-877-STOP-ANS. Species in the news Learning extensions Resources Oregon Public Broadcasting’s Like a Mussel out of Water Invasion of the Quagga Mussels! slide coverage of quagga mussels: www. show: waterbase.uwm.edu/media/ opb.org/programs/ofg/episodes/ cruise/invasion_files/frame.html view/1901 (Only viewable with Microsoft Internet Explorer) Why you should care How they got here and spread These tiny invaders have dramatically changed Zebra and quagga mussels were introduced to the entire ecosystems, and they cost taxpayers billions Great Lakes from the Caspian and Black Sea region of dollars every year. -

Bivalve Distribution in Hydrographic Regions in South America: Historical Overview and Conservation

Hydrobiologia DOI 10.1007/s10750-013-1639-x FRESHWATER BIVALVES Review Paper Bivalve distribution in hydrographic regions in South America: historical overview and conservation Daniel Pereira • Maria Cristina Dreher Mansur • Leandro D. S. Duarte • Arthur Schramm de Oliveira • Daniel Mansur Pimpa˜o • Cla´udia Tasso Callil • Cristia´n Ituarte • Esperanza Parada • Santiago Peredo • Gustavo Darrigran • Fabrizio Scarabino • Cristhian Clavijo • Gladys Lara • Igor Christo Miyahira • Maria Teresa Raya Rodriguez • Carlos Lasso Received: 19 January 2013 / Accepted: 25 July 2013 Ó Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2013 Abstract Based on literature review and malaco- Mycetopodidae and Hyriidae lineages were predom- logical collections, 168 native freshwater bivalve and inant in regions that are richest in species toward the five invasive species have been recorded for 52 East of the continent. The distribution of invasive hydrographic regions in South America. The higher species Limnoperna fortunei is not related to species species richness has been detected in the South richness in different hydrographic regions there. The Atlantic, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Amazon Brazilian species richness and its distribution patterns are hydrographic regions. Presence or absence data were closely associated with the geological history of the analysed by Principal Coordinate for Phylogeny- continent. The hydrographic regions present distinct Weighted. The lineage Veneroida was more represen- phylogenetic and species composition regardless of tative in hydrographic regions that are poorer in the level of richness. Therefore, not only should the species and located West of South America. The richness be considered to be a criterion for prioritizing areas for conservation, but also the phylogenetic diversity of communities engaged in services and Guest editors: Manuel P. -

Effect of Probiotics on the Growth Performance and Survival Rate of the Grooved Carpet Shell Clam Seeds, Ruditapes Decussatus, (Linnaeus, 1758) from the Suez Canal

Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Biology & Fisheries Zoology Department, Faculty of Science, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt. ISSN 1110 – 6131 Vol. 24(7): 531 – 551 (2020) www.ejabf.journals.ekb.eg Effect of probiotics on the growth performance and survival rate of the grooved carpet shell clam seeds, Ruditapes decussatus, (Linnaeus, 1758) from the Suez Canal Mahmoud Sami*, Nesreen K. Ibrahim, Deyaaedin A. Mohammad Department of Marine Science , Faculty of Science, Suez Canal University, Egypt. *Corresponding Author: [email protected] [ ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: The carpet shell clam, Ruditapes decussatus is one of the most popular Received: Sept. 27, 2020 and commercially important bivalves in Egypt. This study aimed to evaluate Accepted: Nov. 8, 2020 the addition of probiotic to fresh algae, yeast and bacteria on growth Online: Nov. 9, 2020 performance and survival rates of the studied species. The experiment was _______________ performed in the Mariculture laboratory, at the Department of Marine Science, Suez Canal University, Ismailia, for 126 days from February 17th to Keywords: June 21th 2018. The experiments were implanted in seven square fiber glass Ruditapes decussatus; tanks with upwelling closed recirculating systems. Six diets were used in probiotic; this experiment in addition to a control. The growth performances were bacteria; determined by measurement of all biometric parameters including shell yeast; length, height, width, total weight, soft body weight and dry weight. The growth performance. highest specific growth rate and growth gain of shell length, height, width and total weight were recorded in diet F (mixed algae + probiotic) while the highest SGR and GG of soft weight and dry weight were recorded in diet D (bacteria + probiotic). -

Lab 5: Phylum Mollusca

Biology 18 Spring, 2008 Lab 5: Phylum Mollusca Objectives: Understand the taxonomic relationships and major features of mollusks Learn the external and internal anatomy of the clam and squid Understand the major advantages and limitations of the exoskeletons of mollusks in relation to the hydrostatic skeletons of worms and the endoskeletons of vertebrates, which you will examine later in the semester Textbook Reading: pp. 700-702, 1016, 1020 & 1021 (Figure 47.22), 943-944, 978-979, 1046 Introduction The phylum Mollusca consists of over 100,000 marine, freshwater, and terrestrial species. Most are familiar to you as food sources: oysters, clams, scallops, and yes, snails, squid and octopods. Some also serve as intermediate hosts for parasitic trematodes, and others (e.g., snails) can be major agricultural pests. Mollusks have many features in common with annelids and arthropods, such as bilateral symmetry, triploblasty, ventral nerve cords, and a coelom. Unlike annelids, mollusks (with one major exception) do not possess a closed circulatory system, but rather have an open circulatory system consisting of a heart and a few vessels that pump blood into coelomic cavities and sinuses (collectively termed the hemocoel). Other distinguishing features of mollusks are: z A large, muscular foot variously modified for locomotion, digging, attachment, and prey capture. z A mantle, a highly modified epidermis that covers and protects the soft body. In most species, the mantle also secretes a shell of calcium carbonate. z A visceral mass housing the internal organs. z A mantle cavity, the space between the mantle and viscera. Gills, when present, are suspended within this cavity. -

The Ecological Significance of Giant Clams in Coral Reef Ecosystems

Biological Conservation 181 (2015) 111–123 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Review The ecological significance of giant clams in coral reef ecosystems ⇑ Mei Lin Neo a,b, William Eckman a, Kareen Vicentuan a,b, Serena L.-M. Teo b, Peter A. Todd a, a Experimental Marine Ecology Laboratory, Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore, 14 Science Drive 4, Singapore 117543, Singapore b Tropical Marine Science Institute, National University of Singapore, 18 Kent Ridge Road, Singapore 119227, Singapore article info abstract Article history: Giant clams (Hippopus and Tridacna species) are thought to play various ecological roles in coral reef Received 14 May 2014 ecosystems, but most of these have not previously been quantified. Using data from the literature and Received in revised form 29 October 2014 our own studies we elucidate the ecological functions of giant clams. We show how their tissues are food Accepted 2 November 2014 for a wide array of predators and scavengers, while their discharges of live zooxanthellae, faeces, and Available online 5 December 2014 gametes are eaten by opportunistic feeders. The shells of giant clams provide substrate for colonization by epibionts, while commensal and ectoparasitic organisms live within their mantle cavities. Giant clams Keywords: increase the topographic heterogeneity of the reef, act as reservoirs of zooxanthellae (Symbiodinium spp.), Carbonate budgets and also potentially counteract eutrophication via water filtering. Finally, dense populations of giant Conservation Epibiota clams produce large quantities of calcium carbonate shell material that are eventually incorporated into Eutrophication the reef framework. Unfortunately, giant clams are under great pressure from overfishing and extirpa- Giant clams tions are likely to be detrimental to coral reefs.