Diagnosis of Insulinoma in a Maine Coon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WELLNESS SCREENING TEST EXPLANATION SHEET We Encourage You to Share All Lab Results with Your Primary Care Provider

WELLNESS SCREENING TEST EXPLANATION SHEET We encourage you to share all lab results with your primary care provider. EXPLANATION OF BLOOD TESTS HEMOGLOBIN A1C: A Hemoglobin A1c level is HEMATOLOGY WELLNESS: expressed as a percent and is used to evaluate the Blood counts are often used as a broad screening test average amount of glucose in the blood over the last to determine an individual’s general health status. 2 to 3 months. This test may be used to screen for and White blood cells are the cells that are part of the diagnose diabetes or risk of developing diabetes. body’s defense system against infections and cancer and also play a role in allergies and inflammation. ALT: This test is used to determine if a patient has Red blood cells are the cells that transport oxygen liver damage. In healthy individuals, ALT levels in the throughout the body. Hemoglobin measures the blood are low and they rise in various disease states. total amount of the oxygen-carrying protein in the blood, which generally reflects the number of red CALCIUM: A calcium test is ordered to screen for, blood cells in the blood. Hematocrit measures the diagnose and monitor a range of conditions percentage of a person’s total blood volume that relating to the bones, heart, nerves, kidneys and consists of red blood cells. Platelets are cell fragments teeth. The test may also be ordered if a person has that are vital for normal blood clotting. symptoms of parathyroid disorder, malabsorption or an overactive thyroid. FREE T4: Free T4 is used to help evaluate thyroid function, generally after determining the TSH is CREATININE: The creatinine blood test is used to abnormal. -

Levels of Serum Uric Acid in Patients with Impaired Glucose Tolerance

JOURNAL OF CRITICAL REVIEWS ISSN- 2394-5125 VOL 08, ISSUE 02, 2021 LEVELS OF SERUM URIC ACID IN PATIENTS WITH IMPAIRED GLUCOSE TOLERANCE 1,2Shahzad Ali Jiskani*, 1Lubna Naz, 3Ali Akbar Pirzado, 4Dolat Singh, 5Asadullah Hanif, 6Razia Bano 1Department of Pathology, Chandka Medical College, SMBBMU, Larkano 2Department of Pathology, Indus Medical College Hospital, Tando Muhammad Khan 3Department of Community Medicine and Public Health, Chadka Medical College, SMBBMU, Larkana 4Department of Medicine, Indus Medical College Hospital, Tando Muhammad Khan 5Health Department, Govt. of Sindh 6Department of Medicine, Liaquat University of Medical & Health Sciences Jamshoro *Corresponding Author: Shahzad Ali Jiskani Department of Pathology, Chandka Medical College, SMBBMU, Larkano ABSTRACT Objective: The main objective of this study is to see levels of serum uric acid in patients having impaired glucose tolerance as compared to normal glucose tolerant individuals. Patients and Methods: This was prospective study, conducted at Department of Medicine and Department of Pathology, Indus Medical College Hospital, Tando Muhammad Khan for the period of 8 months (March 2019 to October 2019). A total of 140 patients were included in this study. An oral glucose test was performed with load of 75g glucose in patients having impaired glucose in fasting. Both normal glucose tolerance and impaired glucose tolerance individuals were evaluated for their serum uric acid level. Serum glucose levels and serum uric acid levels were performed on COBAS C-111 Chemistry Analyzer ensuring procedures of quality control. Data was entered and analyzed using SPSS 21.0. Results: In patients having impaired glucose tolerance, the frequency of hyperuricemia was 62.35%. Analysis of both groups (patients with normal glucose tolerance and glucose intolerance), association was strong with p-value of <0.001. -

C-Reactive Protein and Gamma-Glutamyltransferase

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Experimental Diabetes Research Volume 2010, Article ID 761715, 8 pages doi:10.1155/2010/761715 Clinical Study C-Reactive Protein and Gamma-Glutamyltransferase Concentrations in Relation to the Prevalence of Type 2 Diabetes Diagnosed by Glucose or HbA1c Criteria in Chinese Adults in Qingdao, China J. Ren,1 Z. C. Pang,2 W. G. Gao,3, 4, 5 H. R. Nan,6 S. J. Wang,2 L. Zhang,3, 4, 5 and Q. Qiao3, 4 1 Department of Epidemiology and Health Statistics, Shandong University, Jinan 250012, China 2 Department of Non-Communicable Disease Prevention, Qingdao Municipal Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, no. 175, Shandong Road, Qingdao 266071, China 3 Department of Public Health, University of Helsinki, 00014 Helsinki, Finland 4 Diabetes Unit, Department of Chronic Disease Prevention, National Institute for Health and Welfare, 00014 Helsinki, Finland 5 Qingdao Endocrinology and Diabetes Hospital, 266071 Qingdao, China 6 Hong Kong Institute of Diabetes and Obesity, Hong Kong, China CorrespondenceshouldbeaddressedtoZ.C.Pang,[email protected] Received 13 August 2010; Revised 12 October 2010; Accepted 12 October 2010 Academic Editor: Giuseppe Paolisso Copyright © 2010 J. Ren et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Aims. To investigate the association of C-reactive protein (CRP) and gamma glutamyltransferase (GGT) concentrations with newly diagnosed diabetes defined by either glucose or HbA1c criteria in Chinese adults. Methods. A population-based cross-sectional study was conducted in 2006. Data from 1167 men and 1607 women aged 35–74 years were analyzed. -

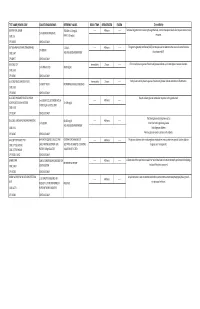

G's- Lab Test Menu

TEST NAME/ PSYCHE CODE COLLECTION GUIDELINES REFERENCE VALUES ROOM TEMP. REFRIGERATED FROZEN Clinical Utility GENTAMICIN, SERUM TROUGH: 0-2.0 mg/dL ------ 48 hours ------ Tests level of gentamicin circulating through the body. Certain therapeutic levels elicit require anti-microbial 2 ml SERUM. REFRIGERATE. CODE: GE PEAK: 5-10 mg/dL response. CPT: 81070 SCHEDULE: DAILY GGT (GAMMA GLUTAMYL TRANSFERASE) 5-31 IU/L ------ 48 hours ------ The gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) test may be used to determine the cause of elevated alkaline 1ml SERUM CODE: GGT AGE AND GENDER DEPENDENT phosphatase (ALP). CPT:82977 SCHEDULE: DAILY GLUCOSE, CSF Immediately 2 hours ------ CFS normally has no glucose. Presence of glucose indicates spinal meningitis or seizure disorders. 1 ml SPINAL FLUID 40-80 mg/mL CODE: GLFL CPT: 82947 SCHEDULE: DAILY GLUCOSE, MISCELLANEOUS FLUID Immediately 2 hours ------ Body fluids normally have no glucose. Presence of glucose indicates infection or inflammation. 1 ml BODY FLUID NO NORMAL RANGE ESTABLISHED CODE: GLFL CPT: 82945 SCHEDULE: DAILY GLUCOSE, PREGNANT RELATED 1 HOUR Results indicate glucose metabolism response to the glucola load. 1 ml SERUM COLLECTED ONE HOUR ------ 48 hours ------ LOADING (O'SULLIVAN SCREEN) 70-139 mg/dL AFTER 50 gm GLUCOSE LOAD CODE: GESC CPT: 82947 SCHEDULE: DAILY The blood glucose test may be used to: GLUCOSE, SERUM (FASTING AND RANDOM) 60-115 mg/dL ------ 48 hours ------ 1 ml SERUM Screen for both high blood glucose AGE AND GENDER DEPENDENT CODE: GLU Help diagnose diabetes CPT: 82947 SCHEDULE: DAILY Monitor glucose levels in persons with diabetes GLUCOSE TOLERANCE TEST 8HR FAST REQUIRED. COLLECT AND CRITERIA FOR DIAGNOSIS OF ------ 48 hours ------ The glucose tolerance test monitors glucose metabolism over a certain time period. -

Clinical Performance of Flash Glucose Monitoring System in Patients With

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Clinical Performance of Flash Glucose Monitoring System in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis and Diabetes Mellitus Dalila Costa1,2 ✉ , Joana Lourenço1, Ana Margarida Monteiro3, Beatriz Castro1, Patricia Oliveira3, Maria Carmo Tinoco3, Vera Fernandes3, Olinda Marques3, Raquel Gonçalves2 & Carla Rolanda1,2 Flash glucose monitoring system (FGMS) is an improved subset of continuous glucose monitoring with a recognized efectiveness on glycemic control, though validation in patients with Liver Cirrhosis (LC) is lacking. To evaluate the accuracy of FGMS in patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (DM) and LC, a prospective, case-control study was performed in 61 ambulatory patients with LC and DM (LC group, n = 31) or DM (Control group, n = 30). During 14 days, patients performed 4 assessments per day of self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG, reference value) followed by FGMS scanning. There were 2567 paired SMBG and FGMS values used in the accuracy analysis, with an overall mean absolute relative diference (MARD) of 12.68% in the LC group and 10.55% in the control group (p < 0,001). In patients with LC, the percentage of readings within Consensus Consensus Error Grid analysis Zone A and A + B were 80.36% and 99,26%, respectively. Sensor clinical accuracy was not afected by factors such as body mass index, age, gender, Child-Pugh score or edematoascitic decompensation. This is the frst study to approach FGMS clinical accuracy in LC, revealing a potential usability of this system to monitor glycemic control in this population. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (DM) has been considered a Public Health challenge due to its signifcant impact on mortality and morbidity worldwide1. -

Journal of Gynecology & Reproductive Medicine

Research Article Journal of Gynecology & Reproductive Medicine The Association Between Hyperuricemia in first Trimester and the Development of Gestational Diabetes Mounir Mohammed Fawzy, Mohamed El-Mandooh Mohamed, Alaa Sayed Hassanin and Mina Nashaat Ghally1* *Corresponding author Resident of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Al-Qussia central Hospital. Mina Nashaat Ghally, Resident of Obstetrics andGynecology, Al-Qussia central Hospital, Egypt. Submitted: 30 June 2017; Accepted: 03 July 2017; Published: 05 July 2017 Abstract Objective: This study aimed to assess the accuracy of the elevation of serum uric acid in the first trimester as a predictive test for development of gestational diabetes mellitus. Patientsand methods: It was a prospective observational study included 200 pregnant patients who were regularly attending the out-patient clinic for routine antenatal care to find if the elevated first trimester uric acid is associated with development of GDM or not. Results: The risk of developing GDM was higher if first-trimester uric acid was < 3.1 mg/dI. Women who developed GDM were significantly older when they compared to women who did not develop GDM [Normal with Mean + SD 24.53 + 4.40 years, Abnormal with Mean + SD 32.78 + 8.18 years, p-value 0.016]. It was found that, the mean BMI was significantly higher in women who developed GDM when compared to women who did not develop GDM [Normal 115 cases of total sample and no one developed GD with Mean + SD, 95.57 + 12.32, Overweight 59 cases, 56 cases (29.3%) were normal and 3 cases (33.3%) had GD with Mean + SD 106.29 + 26.62, Obese 26 cases, 20 cases (10.5%) were normal and 6 cases (66.7%) had GD with Mean + SD 124.27 + 39.78, p-value 0.000]. -

Hyperglycemia – Prediabetes

North Dakota Family Planning Program Clinical Protocol Manual Health Maintenance – HM 8 Hyperglycemia – Prediabetes DEFINITION Hyperglycemia is an excess of glucose in the blood. Prediabetes is a condition when blood glucose levels are higher than normal but not yet high enough to be diagnosed as diabetes. (Prediabetes is also known as Impaired Glucose Tolerance (IGT) or Impaired Fasting Glucose (IFG) depending on which test was used to detect it. IGT uses the oral glucose tolerance test and IFG uses the fasting plasma glucose test.) SUBJECTIVE May include: 1. No symptoms 2. Family history of diabetes 3. Weight changes 4. Fatigue, blurred vision, recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis 5. History of gestational diabetes or birth weight of newborn 9 lbs. or greater 6. Polydipsia, polyphagia, or polyuria 7. 20% over ideal body weight; sedentary lifestyle 8. Decreased wound healing 9. Race (higher incidence of diabetes among American Indian, Hispanic, and African American population) 10. History of hypertension 11. History of decreased HDL and increased triglycerides 12. History of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome or Metabolic Syndrome 13. History of antipsychotic medication therapy OBJECTIVE May include: 1. Blood pressure 2. Height and weight 3. Complete physical exam. Acanthosis Nigricans may be noted in axillae, groin, and/or neck LABORATORY May refer for: 1. Hyperglycemia a. lab of choice may include one or more of the following: i. Fasting plasma glucose (FPG) a) Prediabetes: FPG between 100 mg/dl to 125 mg/dl b) Diabetes: FPG is > 126 mg/dl ii. Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT) a) Prediabetes: OGTT 140mg/dl to 199 mg/dl b) Diabetes: OGTT 200mg/dl or higher iii. -

Standards of Medical Care for Patients with Diabetes Mellitus

POSITION STATEMENT Standards of Medical Care for Patients With Diabetes Mellitus iabetes is a chronic illness that requires contin- Dietary habits, nutritional status, and weight history; uing medical care and education to prevent acute growth and development in children complications and to reduce the risk of long- Details of previous treatment programs, including Dterm complications. People with diabetes should diabetes education receive their treatment and care from physicians with Current treatment of diabetes, including medications, expertise and a special interest in diabetes. The follow- diet, and results of glucose monitoring ing standards define basic (minimum) medical care for Exercise history people with diabetes. These standards are not intended Frequency, severity, and cause of acute complica- to preclude more extensive evaluation and management tions such as ketoacidosis and hypoglycemia of the patient. For more detailed information refer to Prior or current infections, particularly skin, foot, den- Physician's Guide to Insulin-Dependent (Type I) Dia- tal, and genitourinary betes: Diagnosis and Treatment and Physician's Guide Symptoms and treatment of chronic complications to Non-Insulin-Dependent (Type II) Diabetes: Diagnosis associated with diabetes: eye, heart, kidney, nerve, and Treatment. sexual function, peripheral vascular, and cerebral vascular Other medications that may affect blood glucose INITIAL VISIT concentration Risk factors for atherosclerosis: smoking, hyperten- Medical history. The comprehensive medical -

Carbohydrate Tolerance in Hypo- Thyroidism and Hyperthyroidism

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.15.83.184 on 1 January 1940. Downloaded from CARBOHYDRATE TOLERANCE IN HYPO- THYROIDISM AND HYPERTHYROIDISM BY THEODORE CRAWFORD, B.Sc., M.D., F.R.F.P.S.G. (From the Department of Paediatrics, University of Glasgow, and the Biochemical Laboratory, Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Glasgow) Since the beginning of the present century it has been recognized that dis- turbances of thyroid secretion are associated with characteristic alterations of the carbohydrate tolerance (Knopfelmacher, 1904; von Noorden, 1910), and current views upon the nature of the changes remain substantially unaltered. Thus Leyton (1937), in Price's textbook, writes that in hypothyroidism there is considerable increase in the tolerance for dextrose, whilst Beaumont (1937) states that in hypothyroidism sugar tolerance is increased, but that in hyper- thyroidism sugar tolerance is often diminished. Similar statements may be copyright. found in almost any general textbook of medicine. Reports of experimental work, however, reveal less unanimity of opinion. Janney and Isaacson (1918) and von Noorden and Isaac (1927) observed that in hypothyroidism the blood-sugar curve after oral glucose was of flatter type than in normal subjects, and the former workers showed also that the curve became normal under thyroid gland therapy. Knopfelmacher (1904) had previously demonstrated an increased assimilation limit for glucose in cases of myxoedema. Gardiner-Hill, Brett and Smith (1925), on the other hand, obtained precisely http://adc.bmj.com/ opposite results: in fifteen myxoedematous adults they found the blood-sugar curve to be both higher and more prolonged than in normal subjects, whilst administration of thyroid gland substance lowered and shortened the curve. -

On the Analysis of Blood Glucose Levels of Diabetic Patients

Fortune J Health Sci 2021; 4 (1): 257-283 DOI: 10.26502/fjhs021 Original Article On The Analysis of Blood Glucose Levels of Diabetic Patients Onyenanu O. Adaobi1, Iheanyi S. Iwueze2, Emmanuel O. Biu1, Christopher Onyema Arimie3* 1Department of Mathematics and Statistics, University of Port Harcourt, Rivers State 2Department of Mathematics and Statistics, Federal University of Technology Owerri, Imo State, Nigeria 3Department of Radiology, University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Rivers State, Nigeria *Corresponding Author: Christopher Onyema Arimie, Department of Radiology, University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Rivers State, Nigeria; E-mail: [email protected] Received: 09 December 2020; Accepted: 19 December 2020; Published: 16 February 2021 Citation: Onyenanu O. Adaobi, Iheanyi S. Iwueze, Emmanuel O. Biu, Christopher Onyema Arimie. On The Analysis of Blood Glucose Levels of Diabetic Patients. Fortune Journal of Health Sciences 4 (2021): 257-283. Abstract difference between blood glucose testing on arrival Paired observation tests (Paired t-test, Wilcoxon and blood glucose testing after resting for one hour. signed ranked test and Sign test) were employed to The level of change in blood glucose after two hours determine if there is any significant difference for fasting patients was not the same with the level of between fasting blood sugar and oral glucose change two hours after glucose administration. It was tolerance tests of 47 diabetic patients. First, Jarque- concluded that a single fasting blood glucose test is Bera (JB) test was done to check for normality and it sufficient to diagnose diabetes on a visit to the showed that not all the mean differences were laboratory while oral glucose tolerance test normally distributed. -

Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism Supplemental Guide

Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism Supplemental Guide Supplemental Guide: Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism April 2021 1 Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism Supplemental Guide TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 3 PATIENT CARE .............................................................................................................................. 4 History and Physical Examination ................................................................................................ 4 Diagnostic Testing including Labs and Imaging ........................................................................... 6 Therapeutics (Behavioral, Medications, Technology, Radiopharmaceuticals) ............................ 8 Procedures ................................................................................................................................. 10 Dynamic Testing ......................................................................................................................... 12 Provides Clinical Consultation .................................................................................................... 13 Requests Clinical Consultation .................................................................................................. 15 MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE .............................................................................................................. 16 Integration of Pathophysiology -

Understanding Your Lab Values

Understanding Your Lab Values Lab Test Reference Brief Review of Range Laboratory Tests Lipid Panel Triglycerides <150 MG/DL This test measure’s your body’s ability to Major lipid component metabolize fats. It, like cholesterol, is a measure of found in the blood. risk for atherosclerosis and related to heart disease; but, because triglyceride levels are independent of cholesterol level, doctors often want to know both values to make a better evaluation of risk. Because this test is sensitive to diet, it is always measured on a fasting basis, i.e., you cannot have had anything to eat or drink (except water) for 12 hours before your blood is drawn for this test. Cholesterol, Total <200 MG/DL This test is the most commonly used indicator of Major lipid component your risk for atherosclerosis and related heart found in the blood. disease. You’re likely to have this test on a regular basis, if you had a high value at initial testing, if you are trying to lower your cholesterol by diet, or if you’re on a cholesterol-lowering medication. It is reported in milligrams per deciliter. High-density lipoprotein is popularly known as the “good” HDL Cholesterol > or = 40 lipoprotein. It protects against heart disease by helping MG/DL remove excess cholesterol deposited in the arteries. High levels seem to be associated with low incidence of coronary heart disease. In the average man, HDL cholesterol levels Men range from 40 to 50 mg/dL. In the average woman, they range from 50 to 60 mg/dL. HDL cholesterol that's less than 40 to 50 40 mg/dL is low.