Tourism Development in Transition Economies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birdwatching Tour

PIRT “Via Pontica” Birdwatching Tour PROMOTING INNOVATIVE RURAL TOURISM IN THE BLACK SEA BASIN REGION 2014 Table of Contents Birdwatching Sites .......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Armenia ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Bulgaria .................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 18 Georgia ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 36 Turkey ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 51 Technical Requirements, Issues and Solutions ............................................................................................................................................................ 70 Detailed Itinerary ........................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Double Dutch

Double Dutch? Transferring the integrated area approach to Bulgaria Paper for the 2008 Berlin Conference on the Human Dimensions of Global Environmental Change, Berlin, 22-23 February 2008. Carel Dieperink (Utrecht University, Copernicus Institute for Sustainable Development and Innovation, P.O. Box80115, 3508 TC Utrecht, the Netherlands, [email protected] ) Linda van Duivenbode (POVVIK-Mec B.V., Ondiep-zuidzijde, 3551 BW Utrecht, the Netherlands) René Boesten (POVVIK-Mec B.V., Ondiep-zuidzijde, 3551 BW Utrecht, the Netherlands) Abstract National and regional development plans and private sector investment plans guide the development of the Bulgarian coastal zone. Still, the development is focussed on short- term returns and profits. Pressure from the great number of investors combined with competition between municipalities to attract investments, limited national funds to support the needed development of infrastructure and utilities and the weak legal basis for enforcing the top down implementation of the plans contribute further to this short term thinking. Long-term thinking integrating several societal interests is required in order to meet the sustainability challenges. The Dutch integrated area approach is an attempt to integrate several societal interests. So far it has been quite successful. At the request of the Bulgarian government the approach is transferred to Bulgaria in order to develop a vision and a strategy for integrated coastal zone management for the Black Sea coast. The Bulgarian request is also a consequence of the EU Recommendation on Integrated Coastal Zone Management, which urges EU member states to develop a strategic action plan for their coastal areas. With financial support of the Dutch government a Dutch-Bulgarian team is trying to transfer the approach to Bulgaria through the MyCOAST project. -

Microsoft Word

Health Promotion & Preventive Maternal and Child Health Care EuropeAid/122909/D/SER/BG Consortium led by Open Society Institute- Sofia Annex І – Monthly Progress Report – October 2008 V FINAL PROGRESS REPORT SEPTEMBER 2007 – NOVEMBER 2008 MONTHLY PROGRESS REPORT Reporting period 1-31 October 2008 During the reporting period – 1 – 31October 2008, the Consultant worked on the implementation of the following activities planned: Implementation of the primary health program for disadvantaged ethnic minority women and children – start of the preventive medical examinations The statistics for October 2008 show that the following examinations were conducted in the four project regions: October 2008 Region/period Pediatric OG Pap smears Total number of examinations examinations taken examinations Yambol (01.10- 330 330 210 660 25.10.2008) Dobrich (01.10- 682 579 579 626 28.10.2008 г.) Montana (01- 460 430 176 890 31.10.2008) Pazardjik 640 378 351 1018 (01-31.10.2008) Total 2112 1717 1316 3194 In October 2008 all mobile teams continued conducting the preventive examinations at places. In all four project regions the interest towards the examinations is growing. We present specific numbers, information and conclusions for each region: 1 Yambol region In October the OG and pediatric mobile units started visits in locations within the municipalities of Elhovo and Bolyarovo. The OG and pediatric examinations were conducted in accordance with the following schedule in the following locations: Date Location 01.10.2008 Straldzha 02.10.2008 Irechekovo 03.10.2008 Yambol, Kozarevo village 06.10.2008 Kozarevo village 07.10.2008 Straldzha 08.10.2008 Okop village 09.10.2008 Lozenets village 10.10.2008 Boyanovo 13.10.2008 Drazhevo village 14.10.2008 Straldzha, Zimnitsa 15.10.2008 Boyanovo village 16.10.2008 Zimnitsa village 17.10.2008 Malomirovo village 20.10.2008 Mamarchevo, Voden 24.10.2008 Yambol 25.10.2008 Straldzha To support the organization of preventive examinations in new locations, the following meetings were held: • 03.10.2008 г. -

ASN, Vol. 8, No 2, Pages 28–43, 2021 28 Corresponding Author: P

ASN, Vol. 8, No 2, Pages 28–43, 2021 Acta Scientifica Naturalis Former Annual of Konstantin Preslavsky University of Shumen: Chemistry, Physics, Biology, Geography Journal homepage: asn.shu.bg Application of medicinal plants for decorative purposes by the local populatuion on the North Black Sea coast (Bulgaria) Petya Boycheva, Dobri Ivanov, Galina Yaneva Medical University „Prof. D-r Paraskev Stoyanov“, Faculty of Pharmacy, Department of Biology, 84 Tsar Osvoboditel Blvd., 9000 Varna, Bulgaria Abstract: The aim of the present study is to identify medicinal plants used for decorative purposes by the local population along the Northern Black Sea coast (Bulgaria). A survey was conducted in the period 2014- 2020. The interviews with the local population were conducted "face to face" with the help of pre-prepared original questionnaires. The surveyed locals are 709 people from 32 settlements. Respondents were randomly selected. They are of different age groups, gender, ethnicity, education and employment. The folk names of the used medicinal plants are recorded. The results show that a significant proportion of respondents (52.89%) use medicinal plants for decorative purposes. The medicinal plants used for decorative purposes by the locals are 73 species, belonging to 61 genera from 30 families. The present study is part of a larger ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in the region of the North Black Sea coast. Keywords: ethnobotany, medicinal plants, ornamental plants, Northern Black Sea coast Introduction Growing flowering plants is an activity that dates back to ancient times. Acad. Kumarov claims that the flowers are as old as the cultivated plants that served as human food. -

Good and Bad Practices

Good and Bad Practices The stories below are short accounts of how experts and volunteers of the project addressed real life problems of communities in North East Bulgaria and in the Constanta and Galati counties in Romania, across the border. They reveal various aspects of the functioning of the public sector and the quality of the services provided by it. The positive moments that are associated with transparent, accountable and efficient administrations are described as good practices. There are some problematic areas in the public sector, so we have bad practices as well. This project is alerting the public and governments to the necessity for improved functioning of the public sector, improved public monitoring over it and improved networking between civil society and administrations. Establishment of procedure Rositsa Koleva, a reporter from the Pozvanate Daily, a newspaper based in Varna, asked for information about environmental project prepared by Varna Municipality in 2008: a map of noise pollution in the city. The questions were put in a form stipulated by the Law for Access to Public Information (LAPI). In the last day of the legal two week period the municipality answered that the questions were further sent to the competent directorate. After another 14 days the journalist received an answer that the required information is categorized as official because it is part of a project under implementation. The municipality requested the journalist to state a legal interest in the matter. After presentation of proofs that the person is working for the press, there was a general confusion in the administration on how to proceed and what fee to collect for the required written information. -

Study on the Efficacy of Some Herbicides for Weed Controlin in Lavander Field

Research Journal of Agricultural Science, 50 (1 ), 2018 STUDY ON THE EFFICACY OF SOME HERBICIDES FOR WEED CONTROLIN IN LAVANDER FIELD I. ZHELYAZKOV, Vanya DELIBALTOVA, T. KRASTEV Department of Crop Science, Faculty of Agronomy, Agricultural University, 12 Mendeleev str., 4000 Plovdiv, Bulgaria [email protected] Abstract: The experimental study was carried out during the period 2013-2014 in a young lavender field on a soil type of leached chernozem in Tsarichino village, Balchik municipality, Dobrich region - Bulgaria. The test was performed by means of a block method with four repetitions; experimental field area - 15 m2. The experiment included 5 variants and an untreated control: 1) Control – untreated, hand hoeing applied three times; 2) Devrinol 4 F (450 g/l napropamide) at the rate of 400 ml/da; 3) Stomp New 330 EC (330 g/l pendimethalin) at the rate of 400 ml/da; 4) Pledge 50 WP (500 g/kg flumioxazine) at the rate of 8 g/da; 5) Goal 2 E (240 g/l oxyfluorfen) + Dual Gold 960 EC (S-metolachlor 960 g/l) at the rate of 100 + 150 ml/da; 6) Merlin Flex 480 SC (isoxaflutole 240 g/L); antidote (cyprosulfamide 240 g/l) + Adengo (Active substance: isoxaflutole 225 g/l); tiocarbazone-methyl 90 g/l; cyprosulfamide (antidote) 150 g/l at the rate of 42 + 44 ml/da. The aim of the present study was to develop an efficient weed control scheme in a young lavender field, depending on the species composition and density. The analysis of the results showed; the applied herbicides exhibit good efficacy against the annual broad-leaved weeds and a weaker control of the perennial weeds. -

PHARE Grant Tables with Beneficiaries

Phare 2004 Grants table list Name Page Grants awarded under Call for Proposals BG2004/016-711.11.04/ESC/G/CGS published on 24 February 2006 25 Grants awarded under Call for Proposals BG2004/016-711.11.04/ESC/G/GSC-1 published on 07 July 2006 654 Схема за безвъзмездна помощ за стимулиране на публично-частното партньорство 854 GRANT CONTRACTS AWARDED DURING April - November 30th, 2006 905 Grants awarded without a Call for Proposals - BG 2004/016-919.05.01.01 - Support for participation of the 920 Republic of Bulgaria in Community Initiative Interreg III B (CADSES) and Interreg III C Programme Grants awarded under Call for Proposals: BG2004/016-715.02.01: Joint Small Projects Fund between 952 Republic of Bulgaria and Republic of Turkey, published on April 3rd 2006 Grants awarded under Call for Proposals: BG 2004/016-782.01.02/GS: People to People in Actions in Support for Economic Development and Promotion of Employment between Republic of Bulgaria and Republic of 967 Greece, published on March 30th 2006 Grants awarded under Call for Proposals: BG2004/016-782.01.03-03/Grants: Promotion of Nature Protection Actions and Sustainable Development across the border, Republic of Bulgaria and Republic of Greece, 991 published on July 10th 2006 Grants awarded under Call for Proposals: BG2004/016-782.01.06.03/Grants: Promotion of the Cultural, Tourist and Human resources in the Cross-Border region, Republic of Bulgaria and Republic of Greece, published on 1007 July 10th 2006 Grants awarded under Call for Proposals: BG2004/016-783.01.03.01*Grants: Joint Small Project Funds , 1037 Republic of Bulgaria and Republic of Romania, published on July 10th 2006. -

ESIA Russian Sector — Appendix 14.1: Fisheries Study

Appendix 14.1: Fisheries Study URS-EIA-REP-203876 This report has been prepared by MRAG Ltd. on behalf of South Stream Transport B.V. URS-EIA-REP-203876 Executive Summary This report has been prepared as part of the South Stream Offshore Pipeline (referred to throughout this report as “the Project”) as an Appendix to the ESIA Report. It gives a summary of the most important commercial species and fisheries in the Black Sea as a whole then examines the three countries through which the pipeline will pass Bulgaria, Russia and Turkey. For each country the size of the fleet, the economic importance of the fisheries and the possible effects that the Project may have during the Construction and Pre-Commissioning Phase were evaluated. For all three phases it was assessed that, given the information available, the Project would be unlikely to have any discernible effect upon catches outside the normal annual variations for the countries concerned. Bulgaria The Bulgarian fleet had the lowest annual catch of the three countries studied and took only 1% of the Black Sea catch in 2010; only Romania took less (0.05%). All of Bulgaria’s fishing fleet operate within Bulgarian waters inside their 24 NM Contiguous Zone; their distant water fleet was dismantled in the early 1990s and as such have no fishing interests outside of Bulgarian waters. The Project is unlikely to have and distinguishable impact on fish stocks that the fishing industry targets and the effect on the commercial fisheries as a whole is likely to be minimal. Fishing grounds are located in the offshore section of the Project Area which will be affected by the safety exclusion zone during the Construction and Pre-Commissioning Phase when the pipe-lay vessel passes through but this will be temporary and localised, approximately 9 to 10 days per pipeline. -

Á Å Ç Ï Ë À Ò Í Î Електронно Копие Îðèãèíàëúò Купете От Баат Ñ 30% Îòñòúïêà

Á Å Ç Ï Ë À Ò Í Î електронно копие ÎÐÈÃÈÍÀËÚÒ купете от БААТ Ñ 30% ÎÒÑÒÚÏÊÀ Използвани символи / Symbols used in the guide За мястото за настаняване Symbols Accommodation Категория съгласно закона Legal category - stars Брой стаи × брой легла Може да се ползва интернет Number of rooms × Number of beds INTERNET available Общи санитарни възли Климатик Rooms with shared bath and shower Air conditioned BULGARIAN ASSOCIATION FOR ALTERNATIVE TOURISM Собствени санитарни възли Има камина или барбекю Rooms with private bath and shower Fireplace / barbeque available Предлага се храна Паркинг Food can be served Parking available Може клиентите да си готвят Говорими езици Opportunity to cook your own meals Languages spoken by hosts Може да се ползва хладилник Велосипеди под наем Refrigerator available Bike rental Може да се ползва пералня Местен водач Laundry service available Local guide Може да се ползва телефон Занятия по изкуство и занаяти Telephone available Arts and crafts workshops Може да се гледа телевизия Автентична постройка TV / cable available Authentic building За обекти и дейности в района – с разстояние в километри Interesting sites and activities in the area: distances in km Пещера Информационен център 6 Cave 6 Tourist information center Минерален извор Плаж 2 Mineral spring Beach Маркирана пешеходна пътека/ Басейн екопътека Swimming pool 4 Marked eco trail/path 4 Музей, къща-музей Възможности за риболов Museum, house museum Fishing Паметник Цена Нощувка на човек в двойна стая Monument Price Overnight stay p.p. in double room Авторски колектив: Любомир Попйорданов, Кирил Калоянов, Драги пътешественици Елеонора Йосифова, Вера Тодорова, Силвия Банчева Лора Димитрова, Зорица Ставрева, Явор Стоянов В месеците преди това натежало от мисли за кризата лято, съдбата ме от- Издателство ОДИСЕЯ-ИН веде из четирите краища на нашата съвсем не малка за истинския пътешест- www.odysseia-in.com, [email protected] веник страна. -

Summary Strategy for Clld (Compulsory Elements

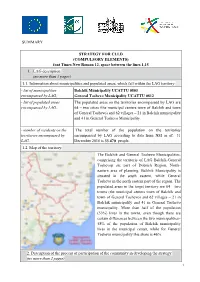

SUMMARY STRATEGY FOR CLLD (COMPULSORY ELEMENTS) font Times New Roman 12, space between the lines 1,15 1. LAG description: (no more than 3 pages) 1.1. Information about municipalities and populated areas, which fall within the LAG territory: - list of municipalities Balchik Municipality UCATTU 0803 encompassed by LAG; General Toshevo Municipality UCATTU 0812 - list of populated areas The populated areas on the territories encompassed by LAG are encompassed by LAG; 64 – two cities (the municipal centers town of Balchik and town of General Toshevo) and 62 villages – 21 in Balchik municipality and 41 in General Toshevo Municipality. - number of residents on the The total number of the population on the territories territories encompassed by encompassed by LAG according to data from NSI as of 31 LAG. December 2016 is 33 470 people. 1.2. Map of the territory: The Balchik and General Toshevo Municipalities, comprising the territoriy of LAG Balchik-General Toshevoр are part of Dobrich Region, North- eastern area of planning. Balchik Municipality is situated in the south eastern, while General Toshevo in the north eastern part of the region. The populated areas in the target territory are 64 – two towns (the municipal centers town of Balchik and town of General Toshevo) and 62 villages – 21 in Balchik municipality and 41 in General Toshevo municipality. More than half of the population (53%) lives in the towns, even though there are certain differences between the two municipalities– 58% of the population of Balchik municipality lives in the municipal center, while for General Toshevo municipality this share is 46%. 2. -

Baltata Managed Reserve

Baltata Managed Reserve The Batova River originates from the village of Kumanovo from the Frangene Plateau, which is located outside the territory of the Balchik State Hunting Farm. It starts as a small stream, which at first runs parallel to the seashore. From the village of Oreshak Aksakovo Municipality, the shape of the valley becomes tortoise, the slopes becoming more leeward at the bottom. In the village of Batovo, the river makes a turn and runs in the eastern direction, as the village of Obrochishte preserves the valley shape and then the river flows into the Black Sea near the Baltata - the form becomes trapezoidal. In general, the river valley extends from the springs to the estuary, where it reaches a width of 10 m. The total length of the Batova River is 39 km, the seabed and the lower stream passing through the area of Balchik State Hunting Farm - 25 km. The bottom of the river in the lower stream is muddy. The Batova River is characterized by: A) Spring high water, from the end of February to May. It is due to the melting of the snow cover, where the water level rises and floods large spaces, especially under the village of Obrochishte, and the northern part of the Baltata forest is flooded with smaller springs. The minimum run-off is 200-300 l / s. B) Summer low waterfall - starting in July and lasting until the end of September. It is characterized by small water quantities of groundwater and summer precipitation. In the past, the Batova River ran through the Baltata Reserve in several sleeves, but in 1930-1935 a canal was drilled through which it flows into the Black Sea. -

Project „Sport for All“ Agreement № 2015 - 3581 / 001 – 001

PROJECT „SPORT FOR ALL“ AGREEMENT № 2015 - 3581 / 001 – 001 Beneficiary: Bulgarian Sports Federation for Children Deprived of Parental Care PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION PERIOD: 02.02.2016-30.06.2017 ACTIVITY 6 ”PROMOTING THE ECONOMIC DIMENSIONS OF SPORT” With the support of the Erasmus+ Programme of the European Union THE PROJECT „SPORT FOR ALL“№ 2015 - 3581 / 001 – 001 IS CO-FUNDED BY THE ERASMUS + PROGRAMME OF THE EU PARTNERS: Balchik Municipality /Bulgaria/ G.S. Rakovski Sports School, Dobrich /Bulgaria/ Association “VERITAS” /Bulgaria/ A.B.A.T. BALKANIA – Balkan Association of Alternative Tourism /FYROM/ The Summer Work & Travel Alumni Macedonia (SWT Alumni) /FYROM/ INNOVAFORM Közhasznú Nonprofit Kft /Hungary/ Timis County Youth Foundation (FITT) /Romania/ Município de Lousada/ Municipality of Lousada /Portugal/ Dinamik Gelisim Dernegi YOUTH NGO /Turkey/ IASIS NGO /Greece/ With the support of the Erasmus+ Programme of the European Union THE PROJECT „SPORT FOR ALL“№ 2015 - 3581 / 001 – 001 IS CO-FUNDED BY THE ERASMUS + PROGRAMME OF THE EU Activity 6 MAIN TARGET GROUPS from the 8 partner countries: • Organizations representing the interests of tourism supply chain • Enterprises and SMEs offering tourism-related activities: Travel agencies; Tourist guides; • Tourism operators; Tourism establishments /hotels, restaurants, holiday villages and etc./, • Sport clubs – from the urban and rural areas for physical activities – private or NGOs • Public or private bodies and organisations active in the field of sport tourism, social tourism,