Unreported in the Court of Special Appeals Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

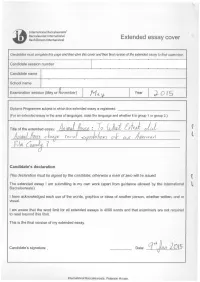

This Cover and Their Final Version Extended

then this cover and their final version extended and whether it is group 1 or Peterson :_:::_.,·. ,_,_::_ ·:. -. \")_>(-_>·...·,: . .>:_'_::°::· ··:_-'./·' . /_:: :·.·· . =)\_./'-.:":_ .... -- __ · ·, . ', . .·· . Stlpervisot1s t~pe>rt ~fld declaration J:h; s3pervi;o(,r;u~f dompietethisreport,. .1ign .the (leclaratton andtfien iiv~.ihe pna:1 ·tersion·...· ofth€7 essay; with this coyerattachedt to the Diploma Programme coordinator. .. .. .. ::,._,<_--\:-.·/·... ":";":":--.-.. ·. ---- .. ,>'. ·.:,:.--: <>=·. ;:_ . .._-,..-_,- -::,· ..:. 0 >>i:mi~ ~;!~;:91'.t~~~1TAt1.tte~) c P1~,§.~p,rmmeht, ;J} a:,ir:lrapriate, on the candidate's perforrnance, .111e. 9q1Jtext ·;n •.w111ctrth~ ..cahdtdatei:m ·.. thft; J'e:~e,~rch.·forf fle ...~X: tendfKI essay, anydifflcu/ties ef1COUntered anq ftCJW thes~\WfJ(fj ()VfJfCOfflf! ·(see .· •tl1i! ext~nciede.ssay guide). The .cpncl(ldipg interview .(vive . vope) ,mt;}y P.fOvidtli .US$ftJf .informf.ltion: pom1r1~nt~ .can .flelp the ex:amr1er award.a ··tevetfot criterion K.th9lisJtcjudgrpentJ. po not. .comment ~pverse personal circumstan9~s that•· m$iiybave . aff.ected the candidate.\lftl'1e cr.rrtotJnt ottime.spiimt qa;ndidate w~s zero, Jt04 must.explain tf1is, fn particular holft!1t was fhf;Jn ppssible .to ;;1.uthentic;at? the essa~ canciidaJe'sown work. You rnay a-ttachan .aclditfonal sherJtJf th.ere isinspfffpi*?nt f pr1ce here,·.···· · Overall, I think this paper is overambitious in its scope for the page length / allowed. I ~elieve it requires furt_her_ editing, as the "making of" portion takes up too ~ large a portion of the essay leaving inadequate page space for reflections on theory and social relevance. The section on the male gaze or the section on race relations in comedy could have served as complete paper topics on their own (although I do appreciate that they are there). -

Rethinking the Nevada Campus Protection Act: Future Challenges & Reaching a Legislative Compromise

15 NEV. L.J. 389 - VASEK.DOCX 3/4/2015 2:56 PM RETHINKING THE NEVADA CAMPUS PROTECTION ACT: FUTURE CHALLENGES & REACHING A LEGISLATIVE COMPROMISE Brian Vasek* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 390 I. CARRYING CONCEALED FIREARMS IN THE STATE OF NEVADA .......... 393 II. THE FUNDAMENTAL RIGHT TO KEEP & BEAR ARMS FOR SELF- DEFENSE ............................................................................................. 394 A. District of Columbia v. Heller..................................................... 395 B. McDonald v. City of Chicago ..................................................... 396 C. Peruta v. County of San Diego ................................................... 397 III. CAMPUS CARRY OPPOSITION & SUPPORT .......................................... 399 A. Primary Arguments of Campus Carry Opponents ...................... 399 B. Primary Arguments of Campus Carry Proponents ..................... 402 IV. CURRENT CAMPUS CARRY LAWS THROUGHOUT THE UNITED STATES ............................................................................................... 406 A. The Utah Model: Full Permission to Campus Carry .................. 407 B. The Oregon Model: Partial Permission to Campus Carry ......... 408 C. The Texas Model: Permission to Carry & Store Firearms in Vehicles ....................................................................................... 409 D. The Nevada Model: No Permission to Campus Carry ................ 411 V. -

List of Dubbed Films by DIMAS

www.dimas.sk List of dubbed films by verzia07|2012 DIMAS - Digital Master Studio ORIGINÁLNY NÁZOV SLOVENSKÝ, /CZ/ DISTRIBUČNÝ NÁZOV 300_ 300_ 2012_ 2012_ 1 ½ KNIGHTS–INSEARCHOFTHERAVISHINGPRINCESSHERZELINDE JEDEN A POL RYTIERA 10 000 BC 10 000 PRED KRISTOM 11_59_00 23_59_00 13 GHOSTS 13 DUCHOV 13 GOING ON 30 CEZ NOC TRIDSIATNIČKOU 15 MINUTES 15 MINÚT 16 BLOCKS 16 BLOKOV 17 AGAIN ZNOVA 17 20,000 LEAGUES UNDER TOMEČEKHE SEA 20 000 MÍĽ POD MOROM 3 LITTLE PIGS 3 MALÉ PRASIATKA 30 000 MILE UNDER THE SEA 30 000 MÍĽ POD MOROM 40 DAYS AND 4O NIGHTS 40 DNÍ A 40 NOCÍ 7 MUMMIES 7 MÚMIÍ 8 SECONDS 8 SEKÚND 8 SIMPLE RULES FORDATINGMYTEENAGDAUGHTER 8 JEDNODUCHÝCH PRAVIDIEL, AKO … 01-28 92 IN THE SHADE 33 VE STÍNU A CHRISTMAS CAROL VIANOČNÁ NÁVŠTEVA A DANGEROUS PLACE NEBEZPEČNÉ MÍSTO A FOOL AND HIS MONEY POSADNUTÝ PENIAZMI /POSEDLÍ PENĚZI A MEMORY IN THE HEART SPOMIENKY V SRDCI A POINT MENT FOR A KILLING DOKTOR SMRŤ A PRICE ABOVE RUBIES DRAHŠIA NEŽ RUBÍNY A ROUND THE WORLD CESTA OKOLO SVETA ZA 80 DNÍ A SIMPLE WISH JEDNODUCHÉ ŽELANIE A WALKING THE CLOUDS PRECHÁDZKA V OBLAKOCH ABRAHAM I ABRAHÁM I ABRAHAM II ABRAHÁM II ABSOLUTE ZERO ABSOLÚTNA NULA ABSOLUTHE TRUTH ABSOLÚTNA PRAVDA ACCEPTED NEPRIJATÝ? FPOHO! ACCUSED AT 17 MOJA DCÉRA NIE JE VRAH ACE VENTURA_ PET DETECTIVE ZVIERACÍ DETEKTÍV ADDAMS FAMILY RODINA ADDAMSOVCOV ADDAMS FAMILY VALUES RODINA ADDAMSOVCOV II ADRIFT ODSÚDENÍ ZOMRIEŤ-OTVORENÉ MORE 2 ADRIFT ÚPLNÉ BEZVETRIE 2 /DVA/ ADVENTURE OF SCAMPER DOBRODRUŽSTVO TUČNIAKA MILKA ADVENTURE OF SHARKBOY AND LAVAGIRL IN 3-D DOBRODRUŽSTVÁ NA PLANÉTE DETÍ ADVENTURES OF BLACK FEATHER DOBRODRUŽSTVÁ ČIERNEHO HAVRANA ADVENTURES OF BLACK FEATHER DOBRODRUŽSTVÁ/DOBRODRUŽSTVÍ ČERNÉHO.. -

National Lampoon's Animal House

From: Reviews and Criticism of Vietnam War Theatrical and Television Dramas (http://www.lasalle.edu/library/vietnam/FilmIndex/home.htm) compiled by John K. McAskill, La Salle University ([email protected]) N2825 NATIONAL LAMPOON’S ANIMAL HOUSE (USA, 1978) (Other titles: American college; Animal house) Credits: director, John Landis ; writers, Harold Ramis, Douglas Kenney, Chris Miller. Cast: John Belushi, Tim Matheson, John Vernon, Thomas Hulce. Summary: Comedy film set at a 1960s Middle Western college. The members of Delta Tau Chi fraternity offend the straight-arrow and up-tight people on campus in a film which irreverently mocks college traditions. One of the villains is an ROTC cadet who, it is noted at the end of the film, was later shot by his own men in Vietnam. Ansen, David. “Movies: Gross out” Newsweek 92 (Aug 7, 1978), p. 85. Barbour, John. [National Lampoon’s animal house] Los Angeles 23 (Sep 1978), p. 240-43. Bartholomew, David. “National Lampoon’s animal house” Film bulletin 47 (Oct/Nov 1978), p. R-F. Biskind, Peter. [National Lampoon’s animal house] Seven days 2/17 (Nov 10, 1978), p. 33. Bookbinder, Robert. The films of the seventies Secaucus, N.J. : Citadel, 1982. (p. 225-28) Braun, Eric. “National Lampoon’s animal house” Films and filming 25/7 (Apr 1979), p. 31-2. Canby, Vincent. “What’s so funny about potheads and toga parties?” New York times 128 (Nov 19, 1978), sec. 2, p. 17. Cook, David A.. Lost illusions : American cinema in the shadow of Watergate and Vietnam, 1970-1979 New York : Scribner’s, 1999. -

African American Radio, WVON, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Chicago

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2012 The Voice of the Negro: African American Radio, WVON, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Chicago Jennifer Searcy Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the African American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Searcy, Jennifer, "The Voice of the Negro: African American Radio, WVON, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Chicago" (2012). Dissertations. 688. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/688 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2013 Jennifer Searcy LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO THE VOICE OF THE NEGRO: AFRICAN AMERICAN RADIO, WVON, AND THE STRUGGLE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS IN CHICAGO A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN AMERICAN HISTORY/PUBLIC HISTORY BY JENNIFER SEARCY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2013 Copyright by Jennifer Searcy, 2013 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my dissertation committee for their feedback throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. As the chair, Dr. Christopher Manning provided critical insights and commentary which I hope has not only made me a better historian, but a better writer as well. As readers, Dr. Lewis Erenberg and Dr. -

September 2015 Orinda News with Extra Page.Indd

Orinda’s #1 News Source! THE ORINDA NEWS Gratis Published by The Orinda Association 12 issues Annually Volume 30, number 9 Delivered to 9,000 households and Businesses in orinda september 2015 Lots of Fun at Orinda Classic Car Show benefi ts Nonprofi ts By SALLY HOGARTY Editor hree Shelby Cobras, several Mustangs, Ttwo Woodies and many more classic cars will ensure lots of fun for local resi- dents as the 11th Annual Classic Car Show rolls into Orinda on Sept. 11-12. “This is really a destination event,” says founder and organizer Chip Herman. “We’ll have a little fun and, hopefully, raise more than a little money for our local nonprof- its.” Beneficiaries of the Classic Car Show include the Orinda Association, Seniors Around Town ride service, Educational Foundation of Orinda, the Orinda Rotary, Orinda Starlight Village Players, Lamorin- da Arts Council, Orinda Chamber of Com- merce, Orinda Parks and Rec Foundation and the Orinda Historical Society Museum. sAllY hoGArtY It all begins on Friday, Sept. 11, at 6 p.m. Getting ready for Dancing with the cars are (l-r) Jim and Sue Breedlove, Candy Kattenburg, Cora Hoxie, Bill Wadsworth and opening the door, chairperson with the popular Dancing with the Cars Barbara Bontemps. the 1957 t-bird shown is owned by orinda resident Eddie Kassick. dinner. Billed as “Fun, Fun, Fun till Her dancing to live music with surf-inspired Daddy Takes the T-Bird Away” (yes, the songs of the Beach Boys and Jan and Senator Glazer Names Orindan car show includes some beautifully restored Dean,” she adds. -

Pre-0Wned DVD's and Blu-Rays Listed on Dougsmovies.Com 2 Family

Pre-0wned DVD’s and Blu-rays Listed on DougsMovies.com Quality: All movies are in excellent condition unless otherwise noted Price: Most single DVD’s are $3.00. Boxed Sets, Multi-packs and hard to find movies are priced accordingly. Volume Discounts: 12-24 items 10% off / 25-49 items 20% off / 50-99 items 30% off / 100 or more items 35% off Payment: We accept PayPal for online orders. We accept cash only for local pick up orders. Shipping: USPS Media Mail. $3.25 for the first item. Add $0.20 for each additional item. Free pick up in Amelia, OH also available. Orders will ship within 24-48 hours of payment. USPS tracking numbers will be provided. Inventory as of 03/18/2021 TITLE Inventory as of 03/18/2021 Format Price 2 Family Time Movies - Seven Alone / The Missouri Traveler DVD 5.00 3 Docudramas (religious themed) Breaking the DaVinci Code / The Miraculous Mission / The Search for Heaven DVD 6.00 4 Sci-Fi Film Collector’s Set The Sender / The Code Conspiracy / The Invader / Storm Trooper DVD 7.50 4 Family Adventure Film Set Spirit Bear / Sign of the Otter / Spirit of the Eagle / White Fang (Still Sealed) DVD 7.50 8 Mile DVD 3.00 12 Rounds DVD 3.00 20 Leading Men – 24 disc set - 0 full length movies featuring actors from the Golden Age of films – Cary Grant, Fred Astaire, James Stewart, etc DVD 10.00 20 Classic Musicals: Legends of Stage and Screeen 4-Disc Boxed Set DVD 10.00 50 Classic Musicals - 12 Disc Boxed Set in Plastic Case – Over 66 hours Boxed Set DVD 15.00 50 First Dates DVD 3.00 50 Hollywood Legends - 50 Movie Pack - 12 Disc -

Title ID Titlename D0043 DEVIL's ADVOCATE D0044 a SIMPLE

Title ID TitleName D0043 DEVIL'S ADVOCATE D0044 A SIMPLE PLAN D0059 MERCURY RISING D0062 THE NEGOTIATOR D0067 THERES SOMETHING ABOUT MARY D0070 A CIVIL ACTION D0077 CAGE SNAKE EYES D0080 MIDNIGHT RUN D0081 RAISING ARIZONA D0084 HOME FRIES D0089 SOUTH PARK 5 D0090 SOUTH PARK VOLUME 6 D0093 THUNDERBALL (JAMES BOND 007) D0097 VERY BAD THINGS D0104 WHY DO FOOLS FALL IN LOVE D0111 THE GENERALS DAUGHER D0113 THE IDOLMAKER D0115 SCARFACE D0122 WILD THINGS D0147 BOWFINGER D0153 THE BLAIR WITCH PROJECT D0165 THE MESSENGER D0171 FOR LOVE OF THE GAME D0175 ROGUE TRADER D0183 LAKE PLACID D0189 THE WORLD IS NOT ENOUGH D0194 THE BACHELOR D0203 DR NO D0204 THE GREEN MILE D0211 SNOW FALLING ON CEDARS D0228 CHASING AMY D0229 ANIMAL ROOM D0249 BREAKFAST OF CHAMPIONS D0278 WAG THE DOG D0279 BULLITT D0286 OUT OF JUSTICE D0292 THE SPECIALIST D0297 UNDER SIEGE 2 D0306 PRIVATE BENJAMIN D0315 COBRA D0329 FINAL DESTINATION D0341 CHARLIE'S ANGELS D0352 THE REPLACEMENTS D0357 G.I. JANE D0365 GODZILLA D0366 THE GHOST AND THE DARKNESS D0373 STREET FIGHTER D0384 THE PERFECT STORM D0390 BLACK AND WHITE D0391 BLUES BROTHERS 2000 D0393 WAKING THE DEAD D0404 MORTAL KOMBAT ANNIHILATION D0415 LETHAL WEAPON 4 D0418 LETHAL WEAPON 2 D0420 APOLLO 13 D0423 DIAMONDS ARE FOREVER (JAMES BOND 007) D0427 RED CORNER D0447 UNDER SUSPICION D0453 ANIMAL FACTORY D0454 WHAT LIES BENEATH D0457 GET CARTER D0461 CECIL B.DEMENTED D0466 WHERE THE MONEY IS D0470 WAY OF THE GUN D0473 ME,MYSELF & IRENE D0475 WHIPPED D0478 AN AFFAIR OF LOVE D0481 RED LETTERS D0494 LUCKY NUMBERS D0495 WONDER BOYS -

Animal House

Today's weather: Our second century of Portly sunny. excellence breezy. high : nea'r60 . Vol. 112 No. 10----= Student Center, University of Delaw-.re, Newark, Del-.ware 19716 Tuesday, October 7, 1986 Christina District residents to vote today 9n tax hike Schools need .more funds plained, is divided into two by Don Gordon parts: Staff Reporter • An allocation of money to . Residents of the Christina build a $5 million elementary School District will vote· today school south of Glasgow High on a referendum which could School and to renovate the 1 John Palmer Elementary J increase taxes for local homeowners to provide more School. THE REVIEW/ Kevin McCready t • A requirement for citizens money for district schools. Mother Nature strikes again - Last Wednesday's electrical storm sends bolts of lightning Dr. Michael Walls, to help pay fo~ supplies and superintendent of the upkeep of schools. through the night. The scene above Towne Court was captured from the fourth floor of Dickinson F. Christina School District, said "We don't have enough if the referendum is passed books to go around," Walls salary." and coordinator of the referen ing the day, or even having homeowners inside district stressed. Pam Connelly (ED 87) a dum, said he expects several two sessions which would at boundaries - which include In addition, citizens' taxes student-teacher at Downes thousand more persons to vote tend school during different residential sections of Newark would help pay for higher Elementary School, said new than did in 1984. parts of the year, Walls said. - will pay an additional 10 teacher salaries. -

List of Dubbed Films by DIMAS

www.dimas.sk List of dubbed films by verzia07|2012 DIMAS - Digital Master Studio ORIGINÁLNY NÁZOV SLOVENSKÝ, /CZ/ DISTRIBUČNÝ NÁZOV 10 000 BC 10 000 PRED KRISTOM WORLD MOST I/01 - 19 112 ŠPECIÁL_BLÍZKO SMRTI I/01-19 AMAZING VIDEOS II/01. - 07. 112 ŠPECIÁL, BLÍZKO SMRTI II/01 - 07 TWELVE MONKEYS 12 OPÍC 13 GHOSTS 13 DUCHOV 15 MINUTES 15 MINÚT 16 BLOCKS 16 BLOKOV 20,000 LEAGUES UNDER TOMEČEKHE SEA 20 000 MÍĽ POD MOROM 2012_ 2012_ 11_59_00 23_59_00 3 LITTLE PIGS 3 MALÉ PRASIATKA BREAKOUT 3 NINDŽOVIA A VYNÁLEZ STOROČIA 30 000 MILE UNDER THE SEA 30 000 MÍĽ POD MOROM 300_ 300_ 92 IN THE SHADE 33 VE STÍNU 40 DAYS AND 4O NIGHTS 40 DNÍ A 40 NOCÍ 7 MUMMIES 7 MÚMIÍ 8 SIMPLE RULES FORDATINGMYTEENAGDAUGHTER 8 JEDNODUCHÝCH PRAVIDIEL, AKO … 01-28 8 SECONDS 8 SEKÚND WHATS UP DOC A ČO ĎALEJ DOKTOR? THE FIRE NEXT TIME I - II A PAK PŘIJDE OHEŇ I - II AND THEN CAME LOVE A POTOM PRIŠLA LÁSKA ABRAHAM I ABRAHÁM I ABRAHAM II ABRAHÁM II ABSOLUTE ZERO ABSOLÚTNA NULA ABSOLUTHE TRUTH ABSOLÚTNA PRAVDA AEON FLUX AEON FLUX THE THOMAS CROWN AFFAIR AFÉRA THOMASA CROWNA STRANGER – HD AGENT BEZ MENA BOURNE IDENTITY AGENT BEZ MINULOSTI OSMOSIS JONES AGENT BIELA KRVINKA AGENT CODY BANKS AGENT CODY BANKS AGENT CODY BANKS 2_DESTINATION LONDON AGENT CODY BANKS DVA THE TAYLOR OF PANAMA AGENT Z PANAMY DOUBLE ZERO AGENTI NULA, NULA THE RELUCTANT AGENT AGENTKOU PROTI SVÉ VULI HALLO ROBIE I 10/01-10 AHOJ ROBI I 17/01-17 HALLO ROBIE II 10/01-10 AHOJ ROBI II 10/01-10 HALLO ROBIE III 10/01 - 10 AHOJ ROBI III 10/01-10 AIRBORNE AIBORNE FRED CLAUS AJ SANTA MÁ BRATA UND ICH LIEBE DICH -

Tim Matheson from Animal House to the White House, Tim Matheson Settles in the Hart of Dixie by Jason Feinberg

CELEB25A TIM Matheson From Animal House to the White House, Tim Matheson Settles in the Hart of Dixie By Jason Feinberg “Take it easy, I’m pre-law.” it has become a staple of Americana cinema television credits he has amassed as an actor, “I thought you were pre-med.” that still stands today as the touchstone for director and producer. “What’s the difference?” every film that features, shall we say, less than That’s just one of the many memorable perfect youth? And fortunately for Matheson Recently, I had the pleasure of sitting down with dialogues from the movie Animal House, (who played a frat boy at age 31), he hasn’t this very talented actor. Having started in show right before Eric “Otter” Stratton gives a great been typecast like some other actors of that business at the tender age of 13, Tim has been speech while the school tries to expel the Delta era, caught in a cycle because of one movie’s in continuous motion since. “I think you have to fraternity. success. In fact, I think a lot of people are constantly reinvent yourself,” he offers, adding surprised and subsequently impressed to see that a performer’s career has a potential half- I can see Tim Matheson reading this, shaking the diversity of the characters Tim can play, life of five to six years and once you’ve used up his head saying, “Great! Another article both prior to and following Otter. Long before one persona, you have to be able to transform mentioning Animal House.” But why not? The Animal House, Tim Matheson was well on his into something else. -

NN 7/17/14 16 Pages Layout 1

BELMONT POINT—Gold dredges are parked at the Snake River shore on Belmont Point, on Friday, July 11. Photo by Lizzy Hahn C VOLUME CXIV NO. 29 July 17, 2014 Council approves Richard Foster Building construction, puts booze and tobacco tax on ballot By Sandra L. Medearis Richard Foster Building. sought more funds. McLain Museum and Beringia to Repair contract The Nome Common Council took The project will showcase the Car- The project manager, architects open and operate within available They saved further consideration up some issues Monday they had rie M. McLain Museum, the library and general contractor cooperated in funds. on a disputed contract for repairing found controversial in the past and and Kawerak’s Beringia Culture and value engineering exercises that re- The Council gave the Richard the City’s light duty and emergency got through them maintaining kind Science Center. duced the construction cost by ap- Foster Building the go-head with the vehicles for a work session. They spirits and light hearts. Cost of the work had been pen- proximately $700,000, bringing the lion’s share of funding secured. continued to deny low bidder Trinity The Council caused spectators to ciled in at $12.2 million and awarded figure down to $10.5 million and re- Sails the contract even though the clap their hands when it passed a res- to SKW, but the Council had held off ducing the overall cost to just under Tax increase on ballot City’s attorney, Patrick Munson, in a olution giving contractor ASRC on giving the starting flag while proj- $19 million.