Animal House Mccloskey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Cover and Their Final Version Extended

then this cover and their final version extended and whether it is group 1 or Peterson :_:::_.,·. ,_,_::_ ·:. -. \")_>(-_>·...·,: . .>:_'_::°::· ··:_-'./·' . /_:: :·.·· . =)\_./'-.:":_ .... -- __ · ·, . ', . .·· . Stlpervisot1s t~pe>rt ~fld declaration J:h; s3pervi;o(,r;u~f dompietethisreport,. .1ign .the (leclaratton andtfien iiv~.ihe pna:1 ·tersion·...· ofth€7 essay; with this coyerattachedt to the Diploma Programme coordinator. .. .. .. ::,._,<_--\:-.·/·... ":";":":--.-.. ·. ---- .. ,>'. ·.:,:.--: <>=·. ;:_ . .._-,..-_,- -::,· ..:. 0 >>i:mi~ ~;!~;:91'.t~~~1TAt1.tte~) c P1~,§.~p,rmmeht, ;J} a:,ir:lrapriate, on the candidate's perforrnance, .111e. 9q1Jtext ·;n •.w111ctrth~ ..cahdtdatei:m ·.. thft; J'e:~e,~rch.·forf fle ...~X: tendfKI essay, anydifflcu/ties ef1COUntered anq ftCJW thes~\WfJ(fj ()VfJfCOfflf! ·(see .· •tl1i! ext~nciede.ssay guide). The .cpncl(ldipg interview .(vive . vope) ,mt;}y P.fOvidtli .US$ftJf .informf.ltion: pom1r1~nt~ .can .flelp the ex:amr1er award.a ··tevetfot criterion K.th9lisJtcjudgrpentJ. po not. .comment ~pverse personal circumstan9~s that•· m$iiybave . aff.ected the candidate.\lftl'1e cr.rrtotJnt ottime.spiimt qa;ndidate w~s zero, Jt04 must.explain tf1is, fn particular holft!1t was fhf;Jn ppssible .to ;;1.uthentic;at? the essa~ canciidaJe'sown work. You rnay a-ttachan .aclditfonal sherJtJf th.ere isinspfffpi*?nt f pr1ce here,·.···· · Overall, I think this paper is overambitious in its scope for the page length / allowed. I ~elieve it requires furt_her_ editing, as the "making of" portion takes up too ~ large a portion of the essay leaving inadequate page space for reflections on theory and social relevance. The section on the male gaze or the section on race relations in comedy could have served as complete paper topics on their own (although I do appreciate that they are there). -

6769 Shary & Smith.Indd

ReFocus: The Films of John Hughes 66769_Shary769_Shary & SSmith.inddmith.indd i 110/03/210/03/21 111:501:50 AAMM ReFocus: The American Directors Series Series Editors: Robert Singer, Frances Smith, and Gary D. Rhodes Editorial Board: Kelly Basilio, Donna Campbell, Claire Perkins, Christopher Sharrett, and Yannis Tzioumakis ReFocus is a series of contemporary methodological and theoretical approaches to the interdisciplinary analyses and interpretations of neglected American directors, from the once-famous to the ignored, in direct relationship to American culture—its myths, values, and historical precepts. The series ignores no director who created a historical space—either in or out of the studio system—beginning from the origins of American cinema and up to the present. These directors produced film titles that appear in university film history and genre courses across international boundaries, and their work is often seen on television or available to download or purchase, but each suffers from a form of “canon envy”; directors such as these, among other important figures in the general history of American cinema, are underrepresent ed in the critical dialogue, yet each has created American narratives, works of film art, that warrant attention. ReFocus brings these American film directors to a new audience of scholars and general readers of both American and Film Studies. Titles in the series include: ReFocus: The Films of Preston Sturges Edited by Jeff Jaeckle and Sarah Kozloff ReFocus: The Films of Delmer Daves Edited by Matthew Carter and Andrew Nelson ReFocus: The Films of Amy Heckerling Edited by Frances Smith and Timothy Shary ReFocus: The Films of Budd Boetticher Edited by Gary D. -

Rethinking the Nevada Campus Protection Act: Future Challenges & Reaching a Legislative Compromise

15 NEV. L.J. 389 - VASEK.DOCX 3/4/2015 2:56 PM RETHINKING THE NEVADA CAMPUS PROTECTION ACT: FUTURE CHALLENGES & REACHING A LEGISLATIVE COMPROMISE Brian Vasek* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 390 I. CARRYING CONCEALED FIREARMS IN THE STATE OF NEVADA .......... 393 II. THE FUNDAMENTAL RIGHT TO KEEP & BEAR ARMS FOR SELF- DEFENSE ............................................................................................. 394 A. District of Columbia v. Heller..................................................... 395 B. McDonald v. City of Chicago ..................................................... 396 C. Peruta v. County of San Diego ................................................... 397 III. CAMPUS CARRY OPPOSITION & SUPPORT .......................................... 399 A. Primary Arguments of Campus Carry Opponents ...................... 399 B. Primary Arguments of Campus Carry Proponents ..................... 402 IV. CURRENT CAMPUS CARRY LAWS THROUGHOUT THE UNITED STATES ............................................................................................... 406 A. The Utah Model: Full Permission to Campus Carry .................. 407 B. The Oregon Model: Partial Permission to Campus Carry ......... 408 C. The Texas Model: Permission to Carry & Store Firearms in Vehicles ....................................................................................... 409 D. The Nevada Model: No Permission to Campus Carry ................ 411 V. -

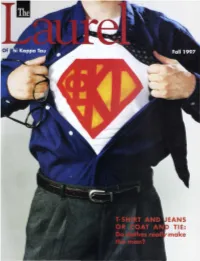

Phi Kcppo Tou Volume 85, No

EANS TIE: make . , .. ' .. .•.. .• •• ~aurelOf Phi Kcppo Tou Volume 85, No. 2, Fall1997 Deadline for Winter: October 15 contentS TerriL. Nackid, Editor William D. jenkins, Business Manager Eli:abeth S. Runyon, Senior Editor James A. Walker, Assistant Editor Contributor this issue: John T. Chafin II COVER It's a bird! It's a plane! It's ...w ell, no, it's not him. Illustrating the conflict between t,shirt and tie; a Phi Tau busts out. More on the clothes debate on page 6. Photo by Ron Kolb, Exposures Unlimited. THE LAUREL is the exoteric publication of The Phi Kappa Tau Foundation. Published prior to 1919 as SIDELIGHTS. A journal devoted to topics related to higher education involving college and alumni interests. Published under the direction and authority of the Board of Trustees of the Phi Departments Kappa Tau Foundation. Editorial Mailing Address: 4 14 North Campus Ave. Mailbox Oxford, OH 45056 [email protected] CONNECTIONS 24 Address Changes: Brothers Across Generations \ 25 Phi Kappa Tau Fraternity 15 North Campus Ave. Phi Tau Laurels 30 Oxford, OH 45056 (513) 523·4193, ext. 221 Alumni News 32 THE LAUREL OF PHI KAPPA TAU is published tri· On Campus 35 annually by The Phi Kappa Tau Foundation, 14 North Campus Avenue, Oxford, OH 45056. Third-class postage Chapter Eternal 4J is paid at Cincinnati, OH 45203, and additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Phi Kappa Tau, 1997-98 Scholarship Winners 43 15 North Campus Avenue, Oxford, OH 45056 Printed in the U.S.A. ISSN Number: 0023-8996 Anything For A Byline 46 Member: The College Fraternity Editors Association From My Side of the Desk 57 Side Roads 61 Cover concept, design and layout by James A. -

List of Dubbed Films by DIMAS

www.dimas.sk List of dubbed films by verzia07|2012 DIMAS - Digital Master Studio ORIGINÁLNY NÁZOV SLOVENSKÝ, /CZ/ DISTRIBUČNÝ NÁZOV 300_ 300_ 2012_ 2012_ 1 ½ KNIGHTS–INSEARCHOFTHERAVISHINGPRINCESSHERZELINDE JEDEN A POL RYTIERA 10 000 BC 10 000 PRED KRISTOM 11_59_00 23_59_00 13 GHOSTS 13 DUCHOV 13 GOING ON 30 CEZ NOC TRIDSIATNIČKOU 15 MINUTES 15 MINÚT 16 BLOCKS 16 BLOKOV 17 AGAIN ZNOVA 17 20,000 LEAGUES UNDER TOMEČEKHE SEA 20 000 MÍĽ POD MOROM 3 LITTLE PIGS 3 MALÉ PRASIATKA 30 000 MILE UNDER THE SEA 30 000 MÍĽ POD MOROM 40 DAYS AND 4O NIGHTS 40 DNÍ A 40 NOCÍ 7 MUMMIES 7 MÚMIÍ 8 SECONDS 8 SEKÚND 8 SIMPLE RULES FORDATINGMYTEENAGDAUGHTER 8 JEDNODUCHÝCH PRAVIDIEL, AKO … 01-28 92 IN THE SHADE 33 VE STÍNU A CHRISTMAS CAROL VIANOČNÁ NÁVŠTEVA A DANGEROUS PLACE NEBEZPEČNÉ MÍSTO A FOOL AND HIS MONEY POSADNUTÝ PENIAZMI /POSEDLÍ PENĚZI A MEMORY IN THE HEART SPOMIENKY V SRDCI A POINT MENT FOR A KILLING DOKTOR SMRŤ A PRICE ABOVE RUBIES DRAHŠIA NEŽ RUBÍNY A ROUND THE WORLD CESTA OKOLO SVETA ZA 80 DNÍ A SIMPLE WISH JEDNODUCHÉ ŽELANIE A WALKING THE CLOUDS PRECHÁDZKA V OBLAKOCH ABRAHAM I ABRAHÁM I ABRAHAM II ABRAHÁM II ABSOLUTE ZERO ABSOLÚTNA NULA ABSOLUTHE TRUTH ABSOLÚTNA PRAVDA ACCEPTED NEPRIJATÝ? FPOHO! ACCUSED AT 17 MOJA DCÉRA NIE JE VRAH ACE VENTURA_ PET DETECTIVE ZVIERACÍ DETEKTÍV ADDAMS FAMILY RODINA ADDAMSOVCOV ADDAMS FAMILY VALUES RODINA ADDAMSOVCOV II ADRIFT ODSÚDENÍ ZOMRIEŤ-OTVORENÉ MORE 2 ADRIFT ÚPLNÉ BEZVETRIE 2 /DVA/ ADVENTURE OF SCAMPER DOBRODRUŽSTVO TUČNIAKA MILKA ADVENTURE OF SHARKBOY AND LAVAGIRL IN 3-D DOBRODRUŽSTVÁ NA PLANÉTE DETÍ ADVENTURES OF BLACK FEATHER DOBRODRUŽSTVÁ ČIERNEHO HAVRANA ADVENTURES OF BLACK FEATHER DOBRODRUŽSTVÁ/DOBRODRUŽSTVÍ ČERNÉHO.. -

Unreported in the Court of Special Appeals Of

UNREPORTED IN THE COURT OF SPECIAL APPEALS OF MARYLAND No. 1928 SEPTEMBER TERM, 2014 HERBERT MAYES v. STATE OF MARYLAND Eyler, Deborah S., Arthur, Salmon, James P. (Retired, Specially Assigned), JJ. Opinion by Eyler, Deborah S., J. Filed: February 26, 2016 *This is an unreported opinion and therefore may not be cited either as precedent or as persuasive authority in any paper, brief, motion, or other document filed in this Court or any other Maryland court. Md. Rule 1-104. – Unreported Opinion – A jury in the Circuit Court for Baltimore City convicted Herbert Mayes, the appellant, of first degree premeditated murder, use of a handgun in a crime of violence, and wearing, carrying, or transporting a handgun. The court sentenced Mayes to life in prison for the murder conviction and a consecutive twenty-year sentence, the first five years to be served without the possibility of parole, for the use of a handgun conviction.1 Mayes presents three questions for review, which we rephrase as follows: I. Did the circuit court err by admitting into evidence prior inconsistent statements of the State’s own witnesses? II. Was there legally sufficient evidence to support Mayes’s conviction for use of a handgun in the commission of a crime of violence? III. Did the circuit court abuse its discretion by ordering Mayes to remain in restraints when the jury returned its verdict? For the following reasons, we shall affirm the judgments of the circuit court. FACTS AND PROCEEDINGS The following facts were adduced at trial.2 Around 11:00 p.m. on March 30, 2012, Chauncey Hardy was shot and killed while standing in front of a building in the 900 block of Valley Street, in Baltimore City. -

National Lampoon's Animal House

From: Reviews and Criticism of Vietnam War Theatrical and Television Dramas (http://www.lasalle.edu/library/vietnam/FilmIndex/home.htm) compiled by John K. McAskill, La Salle University ([email protected]) N2825 NATIONAL LAMPOON’S ANIMAL HOUSE (USA, 1978) (Other titles: American college; Animal house) Credits: director, John Landis ; writers, Harold Ramis, Douglas Kenney, Chris Miller. Cast: John Belushi, Tim Matheson, John Vernon, Thomas Hulce. Summary: Comedy film set at a 1960s Middle Western college. The members of Delta Tau Chi fraternity offend the straight-arrow and up-tight people on campus in a film which irreverently mocks college traditions. One of the villains is an ROTC cadet who, it is noted at the end of the film, was later shot by his own men in Vietnam. Ansen, David. “Movies: Gross out” Newsweek 92 (Aug 7, 1978), p. 85. Barbour, John. [National Lampoon’s animal house] Los Angeles 23 (Sep 1978), p. 240-43. Bartholomew, David. “National Lampoon’s animal house” Film bulletin 47 (Oct/Nov 1978), p. R-F. Biskind, Peter. [National Lampoon’s animal house] Seven days 2/17 (Nov 10, 1978), p. 33. Bookbinder, Robert. The films of the seventies Secaucus, N.J. : Citadel, 1982. (p. 225-28) Braun, Eric. “National Lampoon’s animal house” Films and filming 25/7 (Apr 1979), p. 31-2. Canby, Vincent. “What’s so funny about potheads and toga parties?” New York times 128 (Nov 19, 1978), sec. 2, p. 17. Cook, David A.. Lost illusions : American cinema in the shadow of Watergate and Vietnam, 1970-1979 New York : Scribner’s, 1999. -

African American Radio, WVON, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Chicago

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2012 The Voice of the Negro: African American Radio, WVON, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Chicago Jennifer Searcy Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the African American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Searcy, Jennifer, "The Voice of the Negro: African American Radio, WVON, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Chicago" (2012). Dissertations. 688. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/688 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2013 Jennifer Searcy LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO THE VOICE OF THE NEGRO: AFRICAN AMERICAN RADIO, WVON, AND THE STRUGGLE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS IN CHICAGO A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN AMERICAN HISTORY/PUBLIC HISTORY BY JENNIFER SEARCY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2013 Copyright by Jennifer Searcy, 2013 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my dissertation committee for their feedback throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. As the chair, Dr. Christopher Manning provided critical insights and commentary which I hope has not only made me a better historian, but a better writer as well. As readers, Dr. Lewis Erenberg and Dr. -

September 2015 Orinda News with Extra Page.Indd

Orinda’s #1 News Source! THE ORINDA NEWS Gratis Published by The Orinda Association 12 issues Annually Volume 30, number 9 Delivered to 9,000 households and Businesses in orinda september 2015 Lots of Fun at Orinda Classic Car Show benefi ts Nonprofi ts By SALLY HOGARTY Editor hree Shelby Cobras, several Mustangs, Ttwo Woodies and many more classic cars will ensure lots of fun for local resi- dents as the 11th Annual Classic Car Show rolls into Orinda on Sept. 11-12. “This is really a destination event,” says founder and organizer Chip Herman. “We’ll have a little fun and, hopefully, raise more than a little money for our local nonprof- its.” Beneficiaries of the Classic Car Show include the Orinda Association, Seniors Around Town ride service, Educational Foundation of Orinda, the Orinda Rotary, Orinda Starlight Village Players, Lamorin- da Arts Council, Orinda Chamber of Com- merce, Orinda Parks and Rec Foundation and the Orinda Historical Society Museum. sAllY hoGArtY It all begins on Friday, Sept. 11, at 6 p.m. Getting ready for Dancing with the cars are (l-r) Jim and Sue Breedlove, Candy Kattenburg, Cora Hoxie, Bill Wadsworth and opening the door, chairperson with the popular Dancing with the Cars Barbara Bontemps. the 1957 t-bird shown is owned by orinda resident Eddie Kassick. dinner. Billed as “Fun, Fun, Fun till Her dancing to live music with surf-inspired Daddy Takes the T-Bird Away” (yes, the songs of the Beach Boys and Jan and Senator Glazer Names Orindan car show includes some beautifully restored Dean,” she adds. -

Pre-0Wned DVD's and Blu-Rays Listed on Dougsmovies.Com 2 Family

Pre-0wned DVD’s and Blu-rays Listed on DougsMovies.com Quality: All movies are in excellent condition unless otherwise noted Price: Most single DVD’s are $3.00. Boxed Sets, Multi-packs and hard to find movies are priced accordingly. Volume Discounts: 12-24 items 10% off / 25-49 items 20% off / 50-99 items 30% off / 100 or more items 35% off Payment: We accept PayPal for online orders. We accept cash only for local pick up orders. Shipping: USPS Media Mail. $3.25 for the first item. Add $0.20 for each additional item. Free pick up in Amelia, OH also available. Orders will ship within 24-48 hours of payment. USPS tracking numbers will be provided. Inventory as of 03/18/2021 TITLE Inventory as of 03/18/2021 Format Price 2 Family Time Movies - Seven Alone / The Missouri Traveler DVD 5.00 3 Docudramas (religious themed) Breaking the DaVinci Code / The Miraculous Mission / The Search for Heaven DVD 6.00 4 Sci-Fi Film Collector’s Set The Sender / The Code Conspiracy / The Invader / Storm Trooper DVD 7.50 4 Family Adventure Film Set Spirit Bear / Sign of the Otter / Spirit of the Eagle / White Fang (Still Sealed) DVD 7.50 8 Mile DVD 3.00 12 Rounds DVD 3.00 20 Leading Men – 24 disc set - 0 full length movies featuring actors from the Golden Age of films – Cary Grant, Fred Astaire, James Stewart, etc DVD 10.00 20 Classic Musicals: Legends of Stage and Screeen 4-Disc Boxed Set DVD 10.00 50 Classic Musicals - 12 Disc Boxed Set in Plastic Case – Over 66 hours Boxed Set DVD 15.00 50 First Dates DVD 3.00 50 Hollywood Legends - 50 Movie Pack - 12 Disc -

Title ID Titlename D0043 DEVIL's ADVOCATE D0044 a SIMPLE

Title ID TitleName D0043 DEVIL'S ADVOCATE D0044 A SIMPLE PLAN D0059 MERCURY RISING D0062 THE NEGOTIATOR D0067 THERES SOMETHING ABOUT MARY D0070 A CIVIL ACTION D0077 CAGE SNAKE EYES D0080 MIDNIGHT RUN D0081 RAISING ARIZONA D0084 HOME FRIES D0089 SOUTH PARK 5 D0090 SOUTH PARK VOLUME 6 D0093 THUNDERBALL (JAMES BOND 007) D0097 VERY BAD THINGS D0104 WHY DO FOOLS FALL IN LOVE D0111 THE GENERALS DAUGHER D0113 THE IDOLMAKER D0115 SCARFACE D0122 WILD THINGS D0147 BOWFINGER D0153 THE BLAIR WITCH PROJECT D0165 THE MESSENGER D0171 FOR LOVE OF THE GAME D0175 ROGUE TRADER D0183 LAKE PLACID D0189 THE WORLD IS NOT ENOUGH D0194 THE BACHELOR D0203 DR NO D0204 THE GREEN MILE D0211 SNOW FALLING ON CEDARS D0228 CHASING AMY D0229 ANIMAL ROOM D0249 BREAKFAST OF CHAMPIONS D0278 WAG THE DOG D0279 BULLITT D0286 OUT OF JUSTICE D0292 THE SPECIALIST D0297 UNDER SIEGE 2 D0306 PRIVATE BENJAMIN D0315 COBRA D0329 FINAL DESTINATION D0341 CHARLIE'S ANGELS D0352 THE REPLACEMENTS D0357 G.I. JANE D0365 GODZILLA D0366 THE GHOST AND THE DARKNESS D0373 STREET FIGHTER D0384 THE PERFECT STORM D0390 BLACK AND WHITE D0391 BLUES BROTHERS 2000 D0393 WAKING THE DEAD D0404 MORTAL KOMBAT ANNIHILATION D0415 LETHAL WEAPON 4 D0418 LETHAL WEAPON 2 D0420 APOLLO 13 D0423 DIAMONDS ARE FOREVER (JAMES BOND 007) D0427 RED CORNER D0447 UNDER SUSPICION D0453 ANIMAL FACTORY D0454 WHAT LIES BENEATH D0457 GET CARTER D0461 CECIL B.DEMENTED D0466 WHERE THE MONEY IS D0470 WAY OF THE GUN D0473 ME,MYSELF & IRENE D0475 WHIPPED D0478 AN AFFAIR OF LOVE D0481 RED LETTERS D0494 LUCKY NUMBERS D0495 WONDER BOYS -

Animal House

Today's weather: Our second century of Portly sunny. excellence breezy. high : nea'r60 . Vol. 112 No. 10----= Student Center, University of Delaw-.re, Newark, Del-.ware 19716 Tuesday, October 7, 1986 Christina District residents to vote today 9n tax hike Schools need .more funds plained, is divided into two by Don Gordon parts: Staff Reporter • An allocation of money to . Residents of the Christina build a $5 million elementary School District will vote· today school south of Glasgow High on a referendum which could School and to renovate the 1 John Palmer Elementary J increase taxes for local homeowners to provide more School. THE REVIEW/ Kevin McCready t • A requirement for citizens money for district schools. Mother Nature strikes again - Last Wednesday's electrical storm sends bolts of lightning Dr. Michael Walls, to help pay fo~ supplies and superintendent of the upkeep of schools. through the night. The scene above Towne Court was captured from the fourth floor of Dickinson F. Christina School District, said "We don't have enough if the referendum is passed books to go around," Walls salary." and coordinator of the referen ing the day, or even having homeowners inside district stressed. Pam Connelly (ED 87) a dum, said he expects several two sessions which would at boundaries - which include In addition, citizens' taxes student-teacher at Downes thousand more persons to vote tend school during different residential sections of Newark would help pay for higher Elementary School, said new than did in 1984. parts of the year, Walls said. - will pay an additional 10 teacher salaries.