ED443120.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finding Aid for the James Howard Meredith Collection (MUM00293)

University of Mississippi eGrove Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids Library November 2020 Finding Aid for the James Howard Meredith Collection (MUM00293) Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/finding_aids Recommended Citation James Howard Meredith, Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Finding Aid for the James Howard Meredith Collection (MUM00293) Questions? Contact us! The James Howard Meredith Collection is open for research. Finding Aid for the James Howard Meredith Collection Table of Contents Descriptive Summary Administrative Information Subject Terms Biographical Note Scope and Content Note User Information Related Material Separated Material Arrangement Container List Descriptive Summary Title: James Howard Meredith Collection Dates: 1950-1997 (bulk 1960-1990) Collector: Meredith, James, 1933- Physical Extent: 146 boxes (75 linear feet) Repository: University of Mississippi. Department of Archives and Special Collections. University, MS 38677, USA Identification: MUM00293 Language of Material: English Abstract: Materials documenting the family, educational, and professional life of James Meredith, the first African American to attend the University of Mississippi. Includes a variety of materials relating to Meredith's enrollment process at Ole Miss and his time as a student there, as well as materials from his military service, family, later civil rights activities, and professional endeavors. Administrative Information Processing Information Collection processed by Jennifer Ford, S. E. Sarthou, Andrew Gladman, and Brian O'Flynn, 1998. -

War Crimes Prosecution Watch

WAR CRIMES PROSECUTION FREDERICK K. COX ATCH INTERNATIONAL LAW CENTER W EDITOR IN CHIEF Margaux Day Michael P. Scharf and Brianne M. Draffin, Advisors Volume 3 - Issue 18 MANAGING EDITOR April 28, 2008 Niki Dasarathy War Crimes Prosecution Watch is a bi-weekly e-newsletter that compiles official documents and articles from major news sources detailing and analyzing salient issues pertaining to the investigation and prosecution of war crimes throughout the world. To subscribe, please email [email protected] and type "subscribe" in the subject line. Contents Court of Bosnia & Herzegovina, War Crimes Chamber Court of BiH: Verdict handed down in the Mirko Pekez and Others case Court of BiH: Verdict handed down in the Dušan Fuštar case BIRN Justice Report: Lazarevic et al: Appointment of new Defense attorneys BIRN Justice Report: Mejakic et al: Another hearing closed to the public Court of BiH: Indictment confirmed in the Predrag Bastah and Others case Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia VOA Khmer Source: Opposition Renews Call for Speedy Tribunal Aljazeera: Khmer Rouge leader seeks bail AP: French lawyer for Khmer Rouge challenges Cambodia Court AFP: Cambodian genocide tribunal denies financial mismanagement International Criminal Court Darfur, Sudan Sudan Tribune: Plane carrying Darfur war crimes suspect forced to make emergency landing Human Rights Watch: Justice for Darfur Campaign Launched Reuters: Global court could indict more over Sudan's Darfur Democratic Republic of the Congo (ICC) ICC Press Release: Setting-up -

Newspaper Distribution List

Newspaper Distribution List The following is a list of the key newspaper distribution points covering our Integrated Media Pro and Mass Media Visibility distribution package. Abbeville Herald Little Elm Journal Abbeville Meridional Little Falls Evening Times Aberdeen Times Littleton Courier Abilene Reflector Chronicle Littleton Observer Abilene Reporter News Livermore Independent Abingdon Argus-Sentinel Livingston County Daily Press & Argus Abington Mariner Livingston Parish News Ackley World Journal Livonia Observer Action Detroit Llano County Journal Acton Beacon Llano News Ada Herald Lock Haven Express Adair News Locust Weekly Post Adair Progress Lodi News Sentinel Adams County Free Press Logan Banner Adams County Record Logan Daily News Addison County Independent Logan Herald Journal Adelante Valle Logan Herald-Observer Adirondack Daily Enterprise Logan Republican Adrian Daily Telegram London Sentinel Echo Adrian Journal Lone Peak Lookout Advance of Bucks County Lone Tree Reporter Advance Yeoman Long Island Business News Advertiser News Long Island Press African American News and Issues Long Prairie Leader Afton Star Enterprise Longmont Daily Times Call Ahora News Reno Longview News Journal Ahwatukee Foothills News Lonoke Democrat Aiken Standard Loomis News Aim Jefferson Lorain Morning Journal Aim Sussex County Los Alamos Monitor Ajo Copper News Los Altos Town Crier Akron Beacon Journal Los Angeles Business Journal Akron Bugle Los Angeles Downtown News Akron News Reporter Los Angeles Loyolan Page | 1 Al Dia de Dallas Los Angeles Times -

Fall 2021 Kids OMNIBUS

FALL 2021 RAINCOAST OMNIBUS Kids This edition of the catalogue was printed on May 13, 2021. To view updates, please see the Fall 2021 Raincoast eCatalogue or visit www.raincoast.com Raincoast Books Fall 2021 - Kids Omnibus Page 1 of 266 A Cub Story by Alison Farrell and Kristen Tracy Timeless and nostalgic, quirky and fresh, lightly educational and wholly heartfelt, this autobiography of a bear cub will delight all cuddlers and snugglers. See the world through a bear cub's eyes in this charming book about finding your place in the world. Little cub measures himself up to the other animals in the forest. Compared to a rabbit, he is big. Compared to a chipmunk, he is HUGE. Compared to his mother, he is still a little cub. The first in a series of board books pairs Kristen Tracy's timeless and nostalgic text with Alison Farrell's sweet, endearing art for an adorable treatment of everyone's favorite topic, baby animals. Author Bio Chronicle Books Alison Farrell has a deep and abiding love for wild berries and other foraged On Sale: Sep 28/21 foods. She lives, bikes, and hikes in Portland, Oregon, and other places in the 6 x 9 • 22 pages Pacific Northwest. full-color illustrations throughout 9781452174587 • $14.99 Kristen Tracy writes books for teens and tweens and people younger than Juvenile Fiction / Animals / Baby Animals • Ages 2-4 that, and also writes poetry for adults. She's spent a lot of her life teaching years writing at places like Johnson State College, Western Michigan University, Brigham Young University, 826 Valencia, and Stanford University. -

N Edttof to the Gradtiate: : - T - TA E of CON TENTS OL

June, 1977 .New National BLACK K ____ jSlaclcJ^nitQ MIyyyyy^A n EDTTOf To The Gradtiate: : - T - TA E OF CON TENTS OL . SlAL ^ Notes ^ ° « "Ea .Editorial | ~ eh generation must out of relative Publishers and Carriers of New ~~ obs'zurity discover its mission, National SLACK MONITOR 2 r««« m ' "Nurec 2 fulf, 3jSj^Bj| The Growth of South Carolina ill it, of betray it."^8 State Under The Leadership of Dr. Nance * . .4 We are especially pleased to feature ® MONITOR Microscope 10 .... wr MONITOR Munchings II South Carolina State College at Orange- -J* berg as our cover story in this issue. The ^ Published cooperatively by member last decade's growth and purogram adjust- ^ S publishers of Black Medut, Inc. Dr. ments at the college reflet:t much of the jS ify Calvin Rolark and Dr. Russell shifting circumstances of bl;ack youth as the I! are the national pubtgherfQo-chairmen aftermath of nationwide ci'vil ^5« ofBlack Media, Inc. Ms. Jeanne Jason upheaval. is the executive editor. National The MONITOR Micrc>scope focuses /L r are at Suite 1101, 507 A Fifth Offices some y Kr cr New York, N.Y. 10017. (212)venue. upon of the critica1 issues facing .< £$ I 867-0983. Editorial coordination is black Americans on the domestic and by ...^-1 J ^ x' r Kin 1/ n nt niiirvin u fist v 7^7 wuriu itcnc. i our commcn ts are especially ^4H I kirk, N. Y. lUSlT' appreciated on the Microscope analysis. ^ I Cover Story Pictures: Courtesy of S. We salute, in this graduartion month, all « I Carolina Stale. -

African American Newsline Distribution Points

African American Newsline Distribution Points Deliver your targeted news efficiently and effectively through NewMediaWire’s African−American Newsline. Reach 700 leading trades and journalists dealing with political, finance, education, community, lifestyle and legal issues impacting African Americans as well as The Associated Press and Online databases and websites that feature or cover African−American news and issues. Please note, NewMediaWire includes free distribution to trade publications and newsletters. Because these are unique to each industry, they are not included in the list below. To get your complete NewMediaWire distribution, please contact your NewMediaWire account representative at 310.492.4001. A.C.C. News Weekly Newspaper African American AIDS Policy &Training Newsletter African American News &Issues Newspaper African American Observer Newspaper African American Times Weekly Newspaper AIM Community News Weekly Newspaper Albany−Southwest Georgian Newspaper Alexandria News Weekly Weekly Newspaper Amen Outreach Newsletter Newsletter Annapolis Times Newspaper Arizona Informant Weekly Newspaper Around Montgomery County Newspaper Atlanta Daily World Weekly Newspaper Atlanta Journal Constitution Newspaper Atlanta News Leader Newspaper Atlanta Voice Weekly Newspaper AUC Digest Newspaper Austin Villager Newspaper Austin Weekly News Newspaper Bakersfield News Observer Weekly Newspaper Baton Rouge Weekly Press Weekly Newspaper Bay State Banner Newspaper Belgrave News Newspaper Berkeley Tri−City Post Newspaper Berkley Tri−City Post -

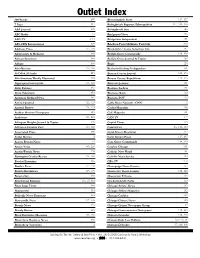

Outlet Index

Outlet Index 600 Words 207 Bloomingdale Press 117, 137 7 Days 217 Bolingbrook Reporter/Metropolitan 117, 140, 146 ABA Journal 185 Bolingbrook Sun 146 ABC Radio 31 Bridgeport News 226 ABC-TV 2, 16 Bridgeview Independent 151 ABS-CBN International 197 Brighton Park/McKinley Park Life 226 Addison Press 117, 136 Brookfield / Lyons Suburban Life 137 Adolescents & Medicine 185 Buffalo Grove Countryside 119, 128 African-Spectrum 189 Buffalo Grove Journal & Topics 128 Afrique 189 Bugle 126 Afro-Netizen 113, 189 Burbank-Stickney Independent 151 Al-Offok Al-Arabi 215 Bureau County Journal 121, 176 Alfa American Weekly Illustrated 203 Bureau County Republican 121, 176 Algonquin Countryside 118, 128 Business Journal 101 Alsip Express 151 Business Ledger 101 Alton Telegraph 153 Business Week 182 American Medical News 182 BusinessPOV 113 Antioch Journal 122, 123 Cable News Network - CNN 2 Antioch Review 118, 123 Cachet Magazine 190 Arabian Horizon Newspaper 215 Café Magazine 101 Arabstreet 113, 215 CAN TV 1, 7 Arlington Heights Journal & Topics 128 Capital Times 153 Arlington Heights Post 119, 128 Capitol Fax Sec 1:34, 109 Associated Press 108 Carol Stream Examiner 137 At the Movies 2 Carol Stream Press 117, 137 Aurora Beacon News 91 Cary-Grove Countryside 118, 129 Austin Voice 189, 224 Catalyst Chicago 101 Austin Weekly News 224 Catholic New World 101 Barrington Courier-Review 118, 128 Catholic News Service 109 Bartlett Examiner 136 CBS-TV 2, 8 Bartlett Press 117, 136 Champaign News Gazette 154 Batavia Republican 117, 136 Charleston Times-Courier 110, -

Questions and Concerns Relating to Special Collections for ABE Students, Including Organization and Kinds of Materials

DOCUMENT RESUME 'ED 247 464 CE 039 567 AUTHOR Weibel, Marguerite Crowley TITLE The Library Literacy Connection. Using Library Resources with Adult Basic Education Students. INSTITUTION Public Library of Columbus and Franklin County, OH. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, DC.; Ohio State Dept. of Education, Columbus.; Ohio State Library, Columbus. PUB DATE Aug 84 NOTE 56p. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adult Basic Education; Adult Literacy; Adult Programs; Adult Students; *Agency Cooperation; *Beginning Reading; Evaluation Criteria; *Library Collections; Library Material Selection; Library Role; *Public Libraries; Readability ABSTRACT This handbook for librarians and adult basic education (ABE) teachers examines existing and potential library-literacy connections. ChapterI discusses methods and criteria for selecting and evaluating books for new readers. Both readability levels and the quality of books are considered. The second chapter examines the library's general collection to find a whole range of materials that can help adult students at all levels from beginning reading through high school equivalency. It acquaints librarians and ABE teachers with the skills that adult new readers must master, the techniques and materials used to teach those skills, and the kinds of materials any public library will have on hand to help new readers develop those skills. Chapter III discusses questions and concerns relating to special collections for ABE students, including organization and kinds of materials. Chapter IV suggests ways public libraries and ABE programs can work together to motivate students to use the public library. A process model for library-ABE cooperation is offered. Appendixes include sources of materials for adult new readers, a classification scheme and evaluation forms for adult new reader materials, a selected bibliography from the general collection, and a bibliography of suggested readings. -

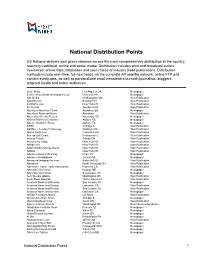

National Distribution Points

National Distribution Points US National delivers your press releases across the most comprehensive distribution in the country, reaching traditional, online and social media. Distribution includes print and broadcast outlets, newswires, online sites, databases and your choice of industry trade publications. Distribution methods include real−time, full−text feeds via the complete AP satellite network, online FTP and content syndicates, as well as personalized email newsletters to reach journalists, bloggers, targeted media and online audiences. 20 de'Mayo Los Angeles CA Newspaper 21st Century Media Newspapers LLC New York NY Newspaper 3BL Media Northampton MA Web Publication 3pointD.com Brooklyn NY Web Publication 401KWire.com New York NY Web Publication 4G Trends Westboro MA Web Publication Aberdeen American News Aberdeen SD Newspaper Aberdeen Business News Aberdeen Web Publication Abernathy Weekly Review Abernathy TX Newspaper Abilene Reflector Chronicle Abilene KS Newspaper Abilene Reporter−News Abilene TX Newspaper ABRN Chicago IL Web Publication ABSNet − Lewtan Technology Waltham MA Web Publication Absolutearts.com Columbus OH Web Publication Access Gulf Coast Pensacola FL Web Publication Access Toledo Toledo OH Web Publication Accounting Today New York NY Web Publication AdAge.com New York NY Web Publication Adam Smith's Money Game New York NY Web Publication Adotas New York NY Web Publication Advance News Publishing Pharr TX Newspaper Advance Newspapers Jenison MI Newspaper Advanced Imaging Pro.com Beltsville MD Web Publication -

Heroes with a Hundred Names: Mythology and Folklore in Robert Penn Warren's Early Fiction

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English 12-2009 Heroes with a Hundred Names: Mythology and Folklore in Robert Penn Warren's Early Fiction Leverett Belton Butts, IV Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Butts, IV, Leverett Belton, "Heroes with a Hundred Names: Mythology and Folklore in Robert Penn Warren's Early Fiction." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/71 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HEROES WITH A HUNDRED NAMES: MYTHOLOGY AND FOLKLORE IN ROBERT PENN WARREN‘S EARLY FICTION by LEVERETT BELTON BUTTS, IV Under the Direction of Thomas McHaney ABSTRACT This dissertation examines Robert Penn Warren‘s use of Arthurian legend, Judeo-Christian folklore, Norse mythology, and ancient vegetation rituals in his first four novels. It also illustrates how the use of these myths helps define Warren‘s Agrarian ideals while underscoring his subtle references to these ideals in his early fiction. INDEX WORDS: Robert Penn Warren, Night Rider, At Heaven‘s Gate, All the King‘s Men, Agrarianism, Southern Agrarianism, The Golden -

****************************W********************************** * Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made * * from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 432 780 CS 216 827 AUTHOR Somers, Albert. B. TITLE Teaching Poetry in High School. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-5289-9 PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 230p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 52899-0015: $14.95 members, $19.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Books (010) Guides - Classroom - Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Class Activities; *English Instruction; High Schools; Internet; *Poetry; *Poets; Student Evaluation; Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS Alternative Assessment ABSTRACT Suggesting that the teaching of poetry must be engaging as well as challenging, this book presents practical approaches, guidelines, activities, and scenarios for teaching poetry in high school. It offers 40 complete poems; a discussion of assessment issues (including authentic assessment); poetry across the curriculum; and addresses and annotations for over 30 websites on poetry. Chapters in the book are (1) Poetry in America; (2) Poetry in the Schools;(3) Selecting Poetry to Teach;(4) Contemporary Poets in the Classroom;(5) Approaching Poetry;(6) Responding to Poetry by Talking;(7) Responding to Poetry by Performing;(8) Poetry and Writing; (9) Teaching Form and Technique;(10) Assessing the Teaching and Learning of Poetry;(11) Teaching Poetry across the Curriculum; and (12) Poetry and the Internet. Appendixes contain lists of approximately 100 anthologies of poetry, 12 reference works, approximately 50 selected mediaresources, 4 selected journals, and 6 selected awards honoring American poets. (RS) *********************************************w********************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. -

Black Newspapers

Black Newspapers Birmingham Times Shoals News Leader Campus Digest 115 Third Ave. West, P.O. Box 10503 412 South Court Street P.O Box1404 Tuskegee University P.O Drawer HH Birmingham, AL 35202 Florence, AL 35630 Tuskegee, AL 36088 Greene County Deomcrat Inner City News Mobile Beacon P.O Box 598 P.O Box 1545 2311 Costarides Street P.O Box 1407 Eutaw, Al 35462 Mobile, AL 36633 Mobile , AL 36633 Montgomery-Tuskegee Times Speakin' Out News African Americans in Alaska Resoures Guide 3900 Birmingham Highway P.O Box 9133 1300 Meridian Street P.O Box 2836 P.O Box 201741 Montgomery, AL 36108 Huntsville, AL 35804 Anchorage, AK 99520 Arkansas State Press Arizona Informat African American News Link Newspaper 221 West 2nd Street Suite 608 1746 East Madsion #2 655 4th Ave. Little Rock, AR 72201 Phoenix, AZ 85034 San Diego, CA 92101 Bakersfield News Observer Berkeley Tri City Post Black Voice News P.O Box 3624 630 Twentieth Street P.O Box 1350 P.O Box 1581 Bakersfield, CA 93385 Oakland, CA 94612 Riverside, CA 92502 Calfornia Advocate Carson Bulletin Central News Wave P.O Box 11826 349 West Compton P.O Box 4248 2621 West 54th Street Fresno, CA 93775 Compton, CA 90224 Los Angeles, CA 90043 http://www.LittleAfrica.com Page 1 Compton Bulletin Exodus Newsmagazine Firestone Park News/Southeast News Press 349 West compton P.O Box 4248 1009 E. Capitol Expwy. #323 P.O Box 19027A Compton, CA 90224 San Jose, CA 95121 Los Angeles, CA 90019 Gospel Women Ingelwood Tribune Los Angeles Sentinel newspaper 710 E.