Bandersnatch, a Standalone Episode of Science–�Ction Series Black Mirror, Presenting Viewers with Interactive Features That Actively Impact the �Lm's Narrative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kijkwijzer (Netherlands Classification) Some Content May Not Be Appropriate for Children This Age

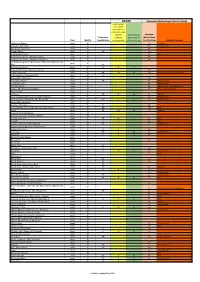

ACCM Kijkwijzer (Netherlands Classification) Some content may not be appropriate for children this age. Parental Content is age Kijkwijzer Australian guidance appropriate for (Netherlands Year Netflix Classification recommended children this age Classification) Kijkwijzer reasons 1 Chance 2 Dance 2014 N 12+ Violence 3 Ninjas: Kick Back 1994 N 6+ Violence; Fear 48 Christmas Wishes 2017 N All A 2nd Chance 2011 N PG All A Christmas Prince 2017 N 6+ Fear A Christmas Prince: The Royal Baby 2019 N All A Christmas Prince: The Royal Wedding 2018 N All A Christmas Special: Miraculous: Tales of Ladybug & Cat 2016 N Noir PG A Cinderella Story 2004 N PG 8 13 A Cinderella Story: Christmas Wish 2019 N All A Dog's Purpose 2017 N PG 10 13 12+ Fear; Drugs and/or alcohol abuse A Dogwalker's Christmas Tale 2015 N G A StoryBots Christmas 2017 N All A Truthful Mother 2019 N PG 6+ Violence; Fear A Witches' Ball 2017 N All Violence; Fear Airplane Mode 2020 N 16+ Violence; Sex; Coarse language Albion: The Enchanted Stallion 2016 N 9+ Fear; Coarse language Alex and Me 2018 N All Saints 2017 N PG 8 10 6+ Violence Alvin and the Chipmunks Meet the Wolfman 2000 N 6+ Violence; Fear Alvin and the Chipmunks: The Road Chip 2015 N PG 7 8 6+ Violence; Fear Amar Akbar Anthony 1977 N Angela's Christmas 2018 N G All Annabelle Hooper and the Ghosts of Nantucket 2016 N PG 12+ Fear Annie 2014 N PG 10 13 6+ Violence Antariksha Ke Rakhwale 2018 N April and the Extraordinary World 2015 N Are We Done Yet? 2007 N PG 8 11 6+ Fear Arrietty 2010 N G 6 9+ Fear Arthur 3 the War of Two -

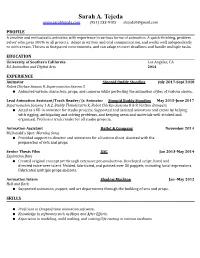

Sarah A. Tejeda (951) 233-9185 [email protected]

Sarah A. Tejeda www.sarahtejeda.com (951) 233-9185 [email protected] PROFILE A creative and enthusiastic animator, with experience in various forms of animation. A quick-thinking, problem solver who gives 100% to all projects. Adept in written and oral communication, and works well independently or with a team. Thrives in fast-paced environments, and can adapt to meet deadlines and handle multiple tasks. EDUCATION University of Southern California Los Angeles, CA BA Animation and Digital Arts 2014 EXPERIENCE Animator Stoopid Buddy Stoodios July 2017-Sept 2018 Robot Chicken Season 9, Supermansion Season 3 ● Animated various characters, props, and cameras while perfecting the animation styles of various shows. Lead Animation Assistant/Track Reader/ Jr. Animator Stoopid Buddy Stoodios May 2015-June 2017 Supermansion Seasons 1 & 2, Buddy Thunderstruck, Robot Chicken Seasons 8 & 9, Verizon Bumpers ● Acted as a fill-in animator for studio projects. Supported and assisted animators and crews by helping with rigging, anticipating and solving problems, and keeping areas and materials well-stocked and organized. Proficient track reader for all studio projects. Animation Assistant Hello! & Company November 2014 McDonald’s Spot: Morning Song ● Provided support to director and animators for a location shoot. Assisted with the preparation of sets and props. Senior Thesis Film USC Jan 2013-May 2014 Expiration Date ● Created original concept art through extensive pre-production. Developed script, hired and directed voice-over talent. Molded, fabricated, and painted over 30 puppets, including facial expressions. Fabricated multiple props and sets. Animation Intern Shadow Machine Jan -May 2012 Hell and Back ● Supported animation, puppet, and art departments through the building of sets and props. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Bob Iger Kevin Mayer Michael Paull Randy Freer James Pitaro Russell

APRIL 11, 2019 Disney Speakers: Bob Iger Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Kevin Mayer Chairman, Direct-to-Consumer & International Michael Paull President, Disney Streaming Services Randy Freer Chief Executive Officer, Hulu James Pitaro Co-Chairman, Disney Media Networks Group and President, ESPN Russell Wolff Executive Vice President & General Manager, ESPN+ Uday Shankar President, The Walt Disney Company Asia Pacific and Chairman, Star & Disney India Ricky Strauss President, Content & Marketing, Disney+ Jennifer Lee Chief Creative Officer, Walt Disney Animation Studios ©Disney Disney Investor Day 2019 April 11, 2019 Disney Speakers (continued): Pete Docter Chief Creative Officer, Pixar Kevin Feige President, Marvel Studios Kathleen Kennedy President, Lucasfilm Sean Bailey President, Walt Disney Studios Motion Picture Productions Courteney Monroe President, National Geographic Global Television Networks Gary Marsh President & Chief Creative Officer, Disney Channel Agnes Chu Senior Vice President of Content, Disney+ Christine McCarthy Senior Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer Lowell Singer Senior Vice President, Investor Relations Page 2 Disney Investor Day 2019 April 11, 2019 PRESENTATION Lowell Singer – Senior Vice President, Investor Relations, The Walt Disney Company Good afternoon. I'm Lowell Singer, Senior Vice President of Investor Relations at THe Walt Disney Company, and it's my pleasure to welcome you to the webcast of our Disney Investor Day 2019. Over the past 1.5 years, you've Had many questions about our direct-to-consumer strategy and services. And our goal today is to answer as many of them as possible. So let me provide some details for the day. Disney's CHairman and CHief Executive Officer, Bob Iger, will start us off. -

Network Totals

Network Totals Total CBS 66 SYNDICATED 66 Netflix 51 Amazon 49 NBC 35 ABC 33 PBS 29 HBO 12 Disney Channel 12 Nickelodeon 12 Disney Junior 9 Food Network 9 Verizon go90 9 Universal Kids 6 Univision 6 YouTube RED 6 CNN en Español 5 DisneyXD 5 YouTube.com 5 OWN 4 Facebook Watch 3 Nat Geo Kids 3 A&E 2 Broadway HD 2 conversationsinla.com 2 Curious World 2 DIY Network 2 Ora TV 2 POP TV 2 venicetheseries.com 2 VICELAND 2 VME TV 2 Cartoon Network 1 Comcast Watchable 1 E! Entertainment 1 FOX 1 Fuse 1 Google Spotlight Stories/YouTube.com 1 Great Big Story 1 Hallmark Channel 1 Hulu 1 ION Television 1 Logo TV 1 manifest99.com 1 MTV 1 Multi-Platform Digital Distribution 1 Oculus Rift, Samsung Gear VR, Google Daydream, HTC Vive, Sony 1 PSVR sesamestreetincommunities.org 1 Telemundo 1 UMC 1 Program Totals Total General Hospital 26 Days of Our Lives 25 The Young and the Restless 25 The Bold and the Beautiful 18 The Bay The Series 15 Sesame Street 13 The Ellen DeGeneres Show 11 Odd Squad 8 Eastsiders 6 Free Rein 6 Harry 6 The Talk 6 Zac & Mia 6 A StoryBots Christmas 5 Annedroids 5 All Hail King Julien: Exiled 4 An American Girl Story - Ivy & Julie 1976: A Happy Balance 4 El Gordo y la Flaca 4 Family Feud 4 Jeopardy! 4 Live with Kelly and Ryan 4 Super Soul Sunday 4 The Price Is Right 4 The Stinky & Dirty Show 4 The View 4 A Chef's Life 3 All Hail King Julien 3 Cop and a Half: New Recruit 3 Dino Dana 3 Elena of Avalor 3 If You Give A Mouse A Cookie 3 Julie's Greenroom 3 Let's Make a Deal 3 Mind of A Chef 3 Pickler and Ben 3 Project Mc² 3 Relationship Status 3 Roman Atwood's Day Dreams 3 Steve Harvey 3 Tangled: The Series 3 The Real 3 Trollhunters 3 Tumble Leaf 3 1st Look 2 Ask This Old House 2 Beat Bugs: All Together Now 2 Blaze and the Monster Machines 2 Buddy Thunderstruck 2 Conversations in L.A. -

Engineering Inc. Provides Expert Analysis on All Issues Affecting the Overall Business of Engineering

FALL 2020 INC.INC. www.acec.orgwww.acec.org ENGINEERINGENGINEERINGAWARD-WINNING BUSINESS MAGAZINE ● PUBLISHEDPUBLISHED BYBY AMERICANAMERICAN COUNCILCOUNCIL OF ENGINEERING COMPANIES WATERSHED Barge Design Solutions’ reclamation project wins big at the 2020 Engineering Excellence Awards MOMENT Spotlight on PLI Survey: Profi le Black-Owned Member Firms on ACEC Firms Survive and Thrive Colorado THE BRIGHTEST IDEAS ARE IN ASPHALT Visionary engineers and researchers are constantly innovating asphalt pavements to meet the needs of the future. They’ve created game-changing products like warm-mix asphalt and Thinlays for pavement preservation — and they’re not done yet. The industry is already working on asphalt roads built to accommodate the safe use of driverless vehicles. This commitment to innovation is paving the way for even longer-lasting, higher-performing pavements. WHEN IT COMES TO INNOVATION ASPHALT PERFORMS LEARN MORE AT WWW.DRIVEASPHALT.ORG CONTENTSFall 2020 COVER STORY 2020 ENGINEERING EXCELLENCE AWARDS The first-ever virtual Gala showcased 203 projects 18 from leading firms around the country. The Copperhill Watershed Restoration in Ducktown, Tennessee, by Barge Design Solutions in Nashville, won the 2020 Grand Conceptor Award. The ACEC Research Institute provides the industry with cutting edge trend data, research and analysis to help firm owners make decisions and arm the Council with information to advance engineering’s essential value to a broad audience. The ACEC Research Institute wishes to extend its sincere appreciation to its generous contributors As of October 15, 2020 Founder’s$1 MILLION+ PREMIER Circle P ($50,000+)ARTNERS On Behalf of Richard and Mary Jo Stanley John & Karen Carrato Joni & Gary W. -

Geopolitics of Numerical Space and the Rule of Algorithms Geopolitika Numeričkog Prostora I Vladavina Algoritama

2311 ISSN 1848-6304 UDK / UDC 316.774:1 Publisher: Centre for Media Philosophy and Research (Zagreb) www.centar-fm.org Editor-in-Chief: Sead Alić www.seadalic.com [email protected] Deputy Editor: Tijana Vukić [email protected] Managing Editor: Nenad Vertovšek [email protected] Secretary: Srećko Brdovčak Mac [email protected] Editorial Board: Frank Hartman (Bauhaus University Weimar, Germany), Predrag Finci (England), Herta Maurer (Alpen-Adria University Klagenfurt, Institute of Slavic Studies, Austria), Izidora Leber (Solo artist, Switzerland), Željko Rutović (Ministry of Culture, Montenegro), Mimo Drašković (Faculty of Maritime Studies, Montenegro), Fahira Fejzić- Čengić (Faculty of Political Sciences, Bosnia and Herzegovina), Rusmir Šadić (Medzlis Islamic Community of Tuzla, Bosnia and Herzegovina), Divna Vuksanović (Faculty of Dramatic Arts, University of Art, Serbia), Slađana Stamenković (Faculty of Sport, Serbia), Dragan Čalović (Faculty of Arts and Design, University of Megatrend, Serbia), Lino Veljak (Faculty of Philosophy University of Zagreb, Croatia), Đorđe Obradović (University of Dubrovnik, Croatia), Ružica Čičak-Chand (Institute for Migration and Ethnic Studies, Croatia), Damir Bralić (University of North, Croatia), Nenad Vertovšek (Department of Croatian Studies at the University of Zadar, Croatia), Slobodan Hadžić (University of North, Presscut, Croatia), Robert Geček (University of North, Croatia), Darijo Čerepinko (University of North, Croatia), Mario Periša (University of North, Croatia), Ivana Greguric (Croatian Studies at the University of Zagreb, Department of Philosophy, Croatia), Tijana Vukić (University of Juraj Dobrila in Pula, Croatia), Vesna Ivezić (Croatia), Jure Vujić (Institute for Geopolitics and Strategic Research, Croatia), Sead Alić (University of North, Croatia) [email protected] Lectors and correctors: Majda Kovač [email protected] Vesna Ivezić [email protected] Layout and placement on the Web: ing. -

Download Download

CINERGIE il cinema e le altre arti 10 ART & Seriality, Repetition and Innovation in Breaking Bad’s Recaps MEDIA FILES and Teasers Introduction I will explore recaps and cold opens in Breaking Bad as serial and cross-medial forms, focusing on the socio-cultural and semiotic mechanism of reinterpretation through narrative condensation or narrative expansion. Condensation means using each episode’s initial recap not only to summarise important actions and dialogues from previous episodes, but also to reopen narrative fragments from previous seasons in order to understand the current episode. In a more expanded medial ecosystem, the ‘internal’ recaps of the series interface with other forms of ‘external’ metanarrative redundancy, such as the synopsis, the encyclopedias and the wikis that can be found online. They also deal with other additive comprehension logics of narrative expansion, such as the offi cial Breaking Bad web episodes, short chapters released online and used to keep the viewers’ expectations high in the time between two seasons. I will analyse how recaps change over the course of the seasons, and how teasers can be aimed at tricking the viewer into false narrative tracks, but also at expanding the narrative storyworld through unexpected short prequels. Audiovisual recaps are paratexts1 given as initial thresholds and intertextual products that interact with the past and present narrative of a series and are designed to build narrative maps for the viewers. Teasers often take the shape of alienating prologues, which obtain to sidetrack the viewer or to anticipate what will happen in the episode2. In this article we basically investigate two serial products as Mittel3 defi nes them: the “retelling” strategy, which includes redundancy and repetition, and the “suspense” strategy, which creates cliff hangers and narrative expectations. -

45Th Annual Daytime Emmy Award Nominations Were Revealed Today on the Emmy Award-Winning Show, the Talk, on CBS

P A G E 1 6 THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES ANNOUNCES NOMINATIONS FOR THE 45th ANNUAL DAYTIME EMMY® AWARDS Mario Lopez & Sheryl Underwood to Host Daytime Emmy Awards to be held on Sunday, April 29 Daytime Creative Arts Emmy® Awards Gala on Friday, April 27 Both Events to Take Place at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium in Southern California New York – March 21, 2018 – The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS) today announced the nominees for the 45th Annual Daytime Emmy® Awards. The ceremony will be held at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium on Sunday, April 29, 2018 hosted by Mario Lopez, host and star of the Emmy award-winning syndicated entertainment news show, Extra, and Sheryl Underwood, one of the hosts of the Emmy award-winning, CBS Daytime program, The Talk. The Daytime Creative Arts Emmy Awards will also be held at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium on Friday, April 27, 2018. The 45th Annual Daytime Emmy Award Nominations were revealed today on the Emmy Award-winning show, The Talk, on CBS. “The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences is excited to be presenting the 45th Annual Daytime Emmy Awards, in the historic Pasadena Civic Auditorium,” said Chuck Dages, Chairman, NATAS. “With an outstanding roster of nominees and two wonderful hosts in Mario Lopez and Sheryl Underwood, we are looking forward to a great event honoring the best that Daytime television delivers everyday to its devoted audience.” “The record-breaking number of entries and the incredible level of talent and craft reflected in this year’s nominees gives us all ample reasons to celebrate,” said David Michaels, SVP, and Executive Producer, Daytime Emmy Awards. -

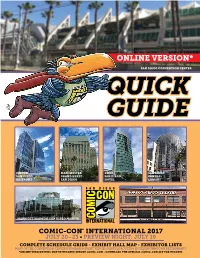

Online Version*

ONLINE VERSION* SAN DIEGO CONVENTION CENTER QUICK GUIDE HILTON MANCHESTER OMNI SAN DIEGO SAN DIEGO GRAND HYATT SAN DIEGO CENTRAL BAYFRONT SAN DIEGO HOTEL LIBRARY MARRIOTT MARQUIS SAN DIEGO MARINA COMIC-CON® INTERNATIONAL 2017 JULY 20–23 • PREVIEW NIGHT: JULY 19 COMPLETE SCHEDULE GRIDS • EXHIBIT HALL MAP • EXHIBITOR LISTS MAPS OF THE CONVENTION CENTER/PROGRAM & EVENT VENUES/SHUTTLE ROUTES & HOTELS/DOWNTOWN RESTAURANTS *ONLINE VERSION WILL NOT BE UPDATED BEFORE COMIC-CON • DOWNLOAD THE OFFICIAL COMIC-CON APP FOR UPDATES COMIC-CON INTERNATIONAL 2017 QUICK GUIDE WELCOME! to the 2017 edition of the Comic-Con International Quick Guide, your guide to the show through maps and the schedule-at-a-glance programming grids! Please remember that the Quick Guide and the Events Guide are once again TWO SEPARATE PUBLICATIONS! For an in-depth look at Comic- Con, including all the program descriptions, pick up a copy of the Events Guide in the Sails Pavilion upstairs at the San Diego Convention Center . and don’t forget to pick up your copy of the Souvenir Book, too! It’s our biggest book ever, chock full of great articles and art! CONTENTS 4 Comic-Con 2017 Programming & Event Locations COMIC-CON 5 RFID Badges • Morning Lines for Exclusives/Booth Signing Wristbands 2017 HOURS 6-7 Convention Center Upper Level Map • Mezzanine Map WEDNESDAY 8 Hall H/Ballroom 20 Maps Preview Night: 9 Hall H Wristband Info • Hall H Next Day Line Map 6:00 to 9:00 PM 10 Rooms 2-11 Line Map THURSDAY, FRIDAY, 11 Hotels and Shuttle Stops Map SATURDAY: 9:30 AM to 7:00 PM* 14-15 Marriott Marquis San Diego Marina Program Information and Maps SUNDAY: 16-17 Hilton San Diego Bayfront Program Information and Maps 9:30 AM to 5:00 PM 18-19 Manchester Grand Hyatt Program Information and Maps *Programming continues into the evening hours on 20 Horton Grand Theatre Program Information and Map Thursday through 21 San Diego Central Library Program Information and Map Saturday nights. -

M Ov Ie Sand E N Te Rta in Ment

Equity Research L O S ANGELES | S A N FRANCISCO | NEW Y O R K | B O S T O N | C H IC A GO | MINNEAPOLIS | MILWAUKEE | SEATTLE Movies and Entertainment January 9, 2017 Michael Pachter Alicia Reese Nick McKay (213) 688-4474 (212) 938-9927 (213) 688-4343 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Biweekly Review -- A Look Ahead from Early January and Our Take on Current Events in Film Exhibition and Video-On-Demand • Q4 box office ended down 3.5% year-over-year to $2.81 billion, while the year ended up 2.2% to $11.4 billion – the second consecutive domestic box office record. October was down 8.1% ($657 million), with the top five films grossing over $50 million each and collectively grossing $306 million during the month. October faced a difficult comparison from The Martian and Hotel Transylvania last year, which, along with number three Goosebumps , totaled $331 million for the month. November was up 7.6% ($959 million), with Doctor Strange, Fantastic Beasts, and Trolls leading the box office and all surpassing $100 million each. December was down 8.8% ($1.2 billion), with Rogue One: A Star Wars Story generating $408 million, compared to December 2015 when The Force Awakens earned $652 million. We expect solid box office growth in 2017, but expect a challenging start to the year given difficult comps in the first quarter. • Premium ticket comparisons were difficult in Q4 and we expect difficult comparisons to a lesser extent in Q1. In Figure 2 on page 3, we compare the top ten films in each quarter to the prior year’s quarter, denoting which was or will be available in IMAX or IMAX 3D. -

BURNAM-THESIS.Pdf

Copyright by Reed Ethan Burnam 2010 The Thesis Committee for Reed Ethan Burnam Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Not Simply for Entertainment: The Failure of Kahani Hamare Mahabharat Ki and its Place in a New Generation of Televised Indian Mythology APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Kathryn Hansen Martha Selby Not Simply for Entertainment: The Failure of Kahani Hamare Mahabharat Ki and its Place in a New Generation of Televised Indian Mythology by Reed Ethan Burnam, B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May, 2010 Dedication This work is dedicated to my grandfather, Paul Wayne Burnam, Ph.D., who received his MBA from the University of Texas in 1939. He always strove to inspire in me the value of education, as well as a good story. We all miss you grandpa. Acknowledgements Many people have been major sources of inspiration and aid in the completion of this project. First, I would like to thank my family, who have always been there for me in every situation. In particular, my mother and step-father for being wonderful and loving parents and friends who would go to any length needed of them in any instance, my father and step-mother for all their enthusiasm and support, and in many ways for their making possible this opportunity for me, and my younger brothers for being great friends and co-conspirators always.