Bbc Response to “The Future of Children's Television

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Managing the BBC's Estate

Managing the BBC’s estate Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General presented to the BBC Trust Value for Money Committee, 3 December 2014 BRITISH BROADCASTING CORPORATION Managing the BBC’s estate Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General presented to the BBC Trust Value for Money Committee, 3 December 2014 Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Culture, Media & Sport by Command of Her Majesty January 2015 © BBC 2015 The text of this document may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as BBC copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. BBC Trust response to the National Audit Office value for money study: Managing the BBC’s estate This year the Executive has developed a BBC Trust response new strategy which has been reviewed by As governing body of the BBC, the Trust is the Trust. In the short term, the Executive responsible for ensuring that the licence fee is focused on delivering the disposal of is spent efficiently and effectively. One of the Media Village in west London and associated ways we do this is by receiving and acting staff moves including plans to relocate staff upon value for money reports from the NAO. to surplus space in Birmingham, Salford, This report, which has focused on the BBC’s Bristol and Caversham. This disposal will management of its estate, has found that the reduce vacant space to just 2.6 per cent and BBC has made good progress in rationalising significantly reduce costs. -

PSB Report Definitions

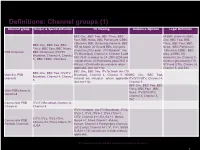

Definitions: Channel groups (1) Channel group Output & Spend definition TV Viewing Audience Opinion Legal Definition BBC One, BBC Two, BBC Three, BBC All BBC channels (BBC Four, BBC News, BBC Parliament, CBBC, One, BBC Two, BBC CBeebies, BBC streaming channels, BBC Three, BBC Four, BBC BBC One, BBC Two, BBC HD (to March 2013) and BBC Olympics News , BBC Parliament Three, BBC Four, BBC News, channels (2012 only). ITV Network* (inc ,CBeebies, CBBC, BBC PSB Channels BBC Parliament, ITV/ITV ITV Breakfast), Channel 4, Channel 5 and Alba, all BBC HD Breakfast, Channel 4, Channel S4C (S4C is added to C4 2008-2009 and channels), the Channel 3 5,, BBC CBBC, CBeebies excluded from 2010 onwards post-DSO in services (provided by ITV, Wales). HD variants are included where STV and UTV), Channel 4, applicable (but not +1s). Channel 5, and S4C. BBC One, BBC Two, ITV Network (inc ITV BBC One, BBC Two, ITV/ITV Main five PSB Breakfast), Channel 4, Channel 5. HD BBC One, BBC Two, Breakfast, Channel 4, Channel channels variants are included where applicable ITV/STV/UTV, Channel 4, 5 (but not +1s). Channel 5 BBC One, BBC Two, BBC Three, BBC Four , BBC Main PSB channels News, ITV/STV/UTV, combined Channel 4, Channel 5, S4C Commercial PSB ITV/ITV Breakfast, Channel 4, Channels Channel 5 ITV+1 Network (inc ITV Breakfast) , ITV2, ITV2+1, ITV3, ITV3+1, ITV4, ITV4+1, CITV, Channel 4+1, E4, E4 +1, More4, CITV, ITV2, ITV3, ITV4, Commercial PSB More4 +1, Film4, Film4+1, 4Music, 4Seven, E4, Film4, More4, 5*, Portfolio Channels 4seven, Channel 4 Paralympics channels 5USA (2012 only), Channel 5+1, 5*, 5*+1, 5USA, 5USA+1. -

Workshop Briefing

King’s Research Portal Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Steemers, J. H., Sakr, N., & Singer, C. (2018). Facilitating Arab-European Dialogue: Consolidated Report on an AHRC Project for Impact and Engagement: Children's Screen Content in an Era of Forced Migration - 8 October 2017 to 3 November 2018. King's College London. Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Media Nations 2019

Media nations: UK 2019 Published 7 August 2019 Overview This is Ofcom’s second annual Media Nations report. It reviews key trends in the television and online video sectors as well as the radio and other audio sectors. Accompanying this narrative report is an interactive report which includes an extensive range of data. There are also separate reports for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The Media Nations report is a reference publication for industry, policy makers, academics and consumers. This year’s publication is particularly important as it provides evidence to inform discussions around the future of public service broadcasting, supporting the nationwide forum which Ofcom launched in July 2019: Small Screen: Big Debate. We publish this report to support our regulatory goal to research markets and to remain at the forefront of technological understanding. It addresses the requirement to undertake and make public our consumer research (as set out in Sections 14 and 15 of the Communications Act 2003). It also meets the requirements on Ofcom under Section 358 of the Communications Act 2003 to publish an annual factual and statistical report on the TV and radio sector. This year we have structured the findings into four chapters. • The total video chapter looks at trends across all types of video including traditional broadcast TV, video-on-demand services and online video. • In the second chapter, we take a deeper look at public service broadcasting and some wider aspects of broadcast TV. • The third chapter is about online video. This is where we examine in greater depth subscription video on demand and YouTube. -

DISCOVER NEW WORLDS with SUNRISE TV TV Channel List for Printing

DISCOVER NEW WORLDS WITH SUNRISE TV TV channel list for printing Need assistance? Hotline Mon.- Fri., 10:00 a.m.–10:00 p.m. Sat. - Sun. 10:00 a.m.–10:00 p.m. 0800 707 707 Hotline from abroad (free with Sunrise Mobile) +41 58 777 01 01 Sunrise Shops Sunrise Shops Sunrise Communications AG Thurgauerstrasse 101B / PO box 8050 Zürich 03 | 2021 Last updated English Welcome to Sunrise TV This overview will help you find your favourite channels quickly and easily. The table of contents on page 4 of this PDF document shows you which pages of the document are relevant to you – depending on which of the Sunrise TV packages (TV start, TV comfort, and TV neo) and which additional premium packages you have subscribed to. You can click in the table of contents to go to the pages with the desired station lists – sorted by station name or alphabetically – or you can print off the pages that are relevant to you. 2 How to print off these instructions Key If you have opened this PDF document with Adobe Acrobat: Comeback TV lets you watch TV shows up to seven days after they were broadcast (30 hours with TV start). ComeBack TV also enables Go to Acrobat Reader’s symbol list and click on the menu you to restart, pause, fast forward, and rewind programmes. commands “File > Print”. If you have opened the PDF document through your HD is short for High Definition and denotes high-resolution TV and Internet browser (Chrome, Firefox, Edge, Safari...): video. Go to the symbol list or to the top of the window (varies by browser) and click on the print icon or the menu commands Get the new Sunrise TV app and have Sunrise TV by your side at all “File > Print” respectively. -

BBC World Service Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General Presented to the BBC Trust Value for Money Committee, 14 June 2016

BBC World Service Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General presented to the BBC Trust Value for Money Committee, 14 June 2016 BRITISH BROADCASTING CORPORATION BBC World Service Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General presented to the BBC Trust Value for Money Committee, 14 June 2016 Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Culture, Media & Sport by Command of Her Majesty June 2016 © BBC 2016 The text of this document may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as BBC copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. BBC Trust response to the National Audit Office value for money review: BBC World Service In the four years to 2014-15 the government BBC Trust response cut core funding to the World Service by As the governing body of the BBC, the around 8% and, in response, the World Trust is responsible for ensuring that the Service reduced its annual expenditure by licence fee is spent efficiently and effectively. £46.8 million. Two thirds of these savings Value-for-money reviews like this one (almost £31 million) have been achieved are an integral part of the governance through greater efficiency and without framework through which the Trust fulfils an impact on audiences. For example, this responsibility. better integration with the BBC newsroom at Broadcasting House has created a The BBC Trust welcomes richer experience for both domestic and the National Audit Office’s international audiences while also saving conclusion that, through its money. -

Media: Industry Overview

MEDIA: INDUSTRY OVERVIEW 7 This document is published by Practical Law and can be found at: uk.practicallaw.com/w-022-5168 Get more information on Practical Law and request a free trial at: www.practicallaw.com This note provides an overview of the sub-sectors within the UK media industry. RESOURCE INFORMATION by Lisbeth Savill, Clare Hardwick, Rachael Astin and Emma Pianta, Latham & Watkins, LLP RESOURCE ID w-022-5168 CONTENTS RESOURCE TYPE • Scope of this note • Publishing and the press Sector note • Film • Podcasts and digital audiobooks CREATED ON – Production • Advertising 13 November 2019 – Financing and distribution • Recorded music JURISDICTION • Television • Video games United Kingdom – Production • Radio – Linear and catch-up television • Social media – Video on-demand and video-sharing services • Media sector litigation SCOPE OF THIS NOTE This note provides an overview of the sub-sectors within the UK media industry. Although the note is broken down by sub-sector, in practice, many of these areas overlap in the converged media landscape. For more detailed notes on media industry sub-sectors, see: • Sector note, Recorded music industry overview. • Sector note, TV and fi lm industry overview. • Practice note, Video games industry overview. FILM Production Total UK spend on feature fi lms in 2017 was £2 billion (up 17% on 2016) (see British Film Institute (BFI): Statistical Yearbook 2018). Film production activity in the UK is driven by various factors, including infrastructure, facilities, availability of skills and creative talent and the incentive of fi lm tax relief (for further information, see Practice note, Film tax relief). UK-produced fi lms can broadly be sub-divided into independent fi lms, UK studio-backed fi lms and non-UK fi lms made in the UK. -

MCPS TV Fpvs

MCPS Broadcast Blanket Distribution - TV FPV Rates paid July 2014 Non Peak Non Peak Progs Progs P(ence) P(ence) Peak FPV Non Peak (covered (covered Manufact Period Rate (per Rate (per (per FPV (per by by Source/S urer Source Link (YYMMYYM weighted weighted weighted weighted blanket blanket Licensee Channel Name hort Code udc Number Type code M) second) second) minute) minute) licence) licence) AATW Ltd Channel AKA CHNAKA S1759 287294 208 qbc 13091312 0.015 0.009 Y Y BBC BBC 1 BBCTVD Z0003 5258 201 qdw 14011403 75.452 37.726 45.2712 22.6356 Y Y BBC BBC 2 BBC2 Z0004 316168 201 qdx 14011403 17.879 8.939 10.7274 5.3634 Y Y BBC BBC ALBA BBCALB Z0008 232662 201 qe2 14011403 6.48 3.24 3.888 1.944 Y Y BBC BBC HD BBCHD Z0010 232654 201 qe4 14011403 6.095 3.047 3.657 1.8282 Y Y BBC BBC Interactive BBCINT AN120 251209 201 qbk 14011403 6.854 4.1124 Y Y BBC BBC News BBC NE Z0007 127284 201 qe1 14011403 8.193 4.096 4.9158 2.4576 Y Y BBC BBC Parliament BBCPAR Z0009 316176 201 qe3 14011403 13.414 6.707 8.0484 4.0242 Y Y BBC BBC Side Agreement for S4C BBCS4C Z0222 316184 201 qip 14011403 7.747 4.6482 Y Y BBC BBC3 BBC3 Z0001 126187 201 qdu 14011403 15.677 7.838 9.4062 4.7028 Y Y BBC BBC4 BBC4 Z0002 158776 201 qdv 14011403 9.205 4.602 5.523 2.7612 Y Y BBC CBBC CBBC Z0005 165235 201 qdy 14011403 8.96 4.48 5.376 2.688 Y Y BBC Cbeebies CBEEBI Z0006 285496 201 qdz 14011403 12.457 6.228 7.4742 3.7368 Y Y BBC Worldwide BBC Entertainment Africa BBCENA Z0296 286601 201 qk2 14011403 5.556 2.778 3.3336 1.6668 N Y BBC Worldwide BBC Entertainment Nordic BBCENN Z0300 -

Platform for Success: Final Report of the Scottish Broadcasting Commission

PLATFORM FOR SUCCESS Final report of the Scottish Broadcasting Commission PLATFORM FOR SUCCESS Final report of the Scottish Broadcasting Commission © Crown copyright 2008 ISBN: 978-0-7559-5845-0 The Scottish Government St Andrew’s House Edinburgh EH1 3DG Produced for the Scottish Broadcasting Commission by RR Donnelley B57086 Published by the Scottish Government, September, 2008 Further copies are available from Blackwell's Bookshop 53 South Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1YS Scottish Broadcasting Commission : 01 CONTENTS Foreword 2 Executive Summary 3 Chapter 1 Introduction 13 Chapter 2 Our Vision for Scottish Broadcasting 15 Chapter 3 Serving Audiences and Society 19 Chapter 4 A Network for Scotland 32 Chapter 5 Broadcasting and the Creative Economy 39 Chapter 6 Delivering the Future 51 Annex 56 02 : Scottish Broadcasting Commission FOREWORD In its short existence, the Scottish Broadcasting Commission has triggered a wide-ranging and frequently passionate debate about the future of the industry and the services it provides to audiences in Scotland. We intended from the beginning to make an impact which would lead to action, and there have been some encouraging early results in the form of new commitments from the broadcasters. But this is only a start. In publishing our final report and recommendations, we hope and expect that the debate will become even more visible and audible – with particular focus on the key opportunities and challenges we have identified in broadcasting and the new digital platforms. What has been refreshing is the extent to which both the industry and its audiences are at least as excited about the future as they are critical of some of the weaknesses of the past and present. -

A Channel Guide

Intelsat is the First MEDIA Choice In Africa Are you ready to provide top media services and deliver optimal video experience to your growing audiences? With 552 channels, including 50 in HD and approximately 192 free to air (FTA) channels, Intelsat 20 (IS-20), Africa’s leading direct-to- home (DTH) video neighborhood, can empower you to: Connect with Expand Stay agile with nearly 40 million your digital ever-evolving households broadcasting reach technologies From sub-Saharan Africa to Western Europe, millions of households have been enjoying the superior video distribution from the IS-20 Ku-band video neighborhood situated at 68.5°E orbital location. Intelsat 20 is the enabler for your TV future. Get on board today. IS-20 Channel Guide 2 CHANNEL ENC FR P CHANNEL ENC FR P 947 Irdeto 11170 H Bonang TV FTA 12562 H 1 Magic South Africa Irdeto 11514 H Boomerang EMEA Irdeto 11634 V 1 Magic South Africa Irdeto 11674 H Botswana TV FTA 12634 V 1485 Radio Today Irdeto 11474 H Botswana TV FTA 12657 V 1KZN TV FTA 11474 V Botswana TV Irdeto 11474 H 1KZN TV Irdeto 11594 H Bride TV FTA 12682 H Nagravi- Brother Fire TV FTA 12562 H 1KZN TV sion 11514 V Brother Fire TV FTA 12602 V 5 FM FTA 11514 V Builders Radio FTA 11514 V 5 FM Irdeto 11594 H BusinessDay TV Irdeto 11634 V ABN FTA 12562 H BVN Europa Irdeto 11010 H Access TV FTA 12634 V Canal CVV International FTA 12682 H Ackermans Stores FTA 11514 V Cape Town TV Irdeto 11634 V ACNN FTA 12562 H CapeTalk Irdeto 11474 H Africa Magic Epic Irdeto 11474 H Capricorn FM Irdeto 11170 H Africa Magic Family Irdeto -

Annual Report on the BBC 2019/20

Ofcom’s Annual Report on the BBC 2019/20 Published 25 November 2020 Raising awarenessWelsh translation available: Adroddiad Blynyddol Ofcom ar y BBC of online harms Contents Overview .................................................................................................................................... 2 The ongoing impact of Covid-19 ............................................................................................... 6 Looking ahead .......................................................................................................................... 11 Performance assessment ......................................................................................................... 16 Public Purpose 1: News and current affairs ........................................................................ 24 Public Purpose 2: Supporting learning for people of all ages ............................................ 37 Public Purpose 3: Creative, high quality and distinctive output and services .................... 47 Public Purpose 4: Reflecting, representing and serving the UK’s diverse communities .... 60 The BBC’s impact on competition ............................................................................................ 83 The BBC’s content standards ................................................................................................... 89 Overview of our duties ............................................................................................................ 96 1 Overview This is our third -

Researching Digital on Screen Graphics Executive Sum M Ary

Researching Digital On Screen Graphics Executive Sum m ary Background In Spring 2010, the BBC commissioned independent market research company, Ipsos MediaCT to conduct research into what the general public, across the UK thought of Digital On Screen Graphics (DOGs) – the channel logos that are often in the corner of the TV screen. The research was conducted between 5th and 11th March, with a representative sample of 1,031 adults aged 15+. The research was conducted by interviewers in-home, using the Ipsos MORI Omnibus. The key findings from the research can be found below. Key Findings Do viewers notice DOGs? As one of our first questions we split our sample into random halves and showed both halves a typical image that they would see on TV. One was a very busy image, with a DOG present in the top left corner, the other image had much less going on, again with the DOG in the top left corner. We asked respondents what the first thing they noticed was, and then we asked what they second thing they noticed was. It was clear from the results that the DOGs did not tend to stand out on screen, with only 12% of those presented with the ‘less busy’ screen picking out the DOG (and even fewer, 7%, amongst those who saw the busy screen). Even when we had pointed out DOGs and talked to respondents specifically about them, 59% agreed that they ‘tend not to notice the logos’, with females and viewers over 55, the least likely to notice them according to our survey.