Resouces and Issues: History of the Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo) National Historic Trail Progress Report Summer 2015

Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo) National Historic Trail Progress Report Summer 2015 Administrator’s Corner Greetings, Trail Fit? Are you up for the challenge? A trail hike or run can provide unique health results that cannot be achieved indoors on a treadmill while staring at a wall or television screen. Many people know instinctively that a walk on a trail in the woods will also clear the mind. There is a new generation that is already part of the fitness movement and eager for outdoor adventure of hiking, cycling, and horseback riding-yes horseback riding is exercise not only for the horse, but also the rider. We are encouraging people to get out on the Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo) National Historic Trail Photo Service Forest U.S. (NPNHT) and Auto Tour Route to enjoy the many health Sandra Broncheau-McFarland benefits it has to offer. Remember to hydrate during these hot summer months. The NPNHT and Auto Tour Route is ripe for exploration! There are many captivating places and enthralling landscapes. Taking either journey - the whole route or sections, one will find unique and authentic places like nowhere else. Wherever one goes along the Trail or Auto Tour Route, they will encounter moments that will be forever etched in their memory. It is a journey of discovery. The Trail not only provides alternative routes to destinations throughout the trail corridor, they are destinations in themselves, each with a unique personality. This is one way that we can connect people to place across time. We hope you explore the trail system as it provides opportunities for bicycling, walking, hiking, running, skiing, horseback riding, kayaking, canoeing, and other activities. -

ALL HAZARD MITIGATION PLAN January 2020

County of Nez Perce ALL HAZARD MITIGATI ON PLAN A January 2020 INCLUDING THE JURISDICTIONS OF: Lewiston Culdesac Peck (in the State of Idaho) 0 1 TITLE PAGE County of Nez Perce ALL HAZARD MITIGATION PLAN Including the Jurisdictions of: Lewiston Culdesac Peck (in the State of Idaho) APPROVED - January 21, 2020 - January 20, 2025 UPDATE: March 24, 2021 Submitted by: Nez Perce County All Hazards Mitigation Plan Steering Committee & Nez Perce County Office of Emergency Management Approved date: January 21, 2020 Cover Photo Credit: Molly Konen – NPC Imaging Dept County of Nez Perce AHMP – January 2020 2 TITLETABLE PAGE OF CONTENTS Title Page ................................................................................................................................... 1 Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................... 2 Mission Statement ...................................................................................................................... 3 Background ................................................................................................................................ 4 Purpose ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Definitions ................................................................................................................................... 6 Methodology .............................................................................................................................. -

2021 Spring General Council Report

NEZ PERCE TRIBE GENERAL COUNCIL SEMIANNUAL REPORT · SPRING 2021 Nez Perce Tribe General Council Spring 2021 1 2 2020-2021 Nez Perce Tribal Executive Committee BACK ROW Quintin Arthur Shannon Ferris Casey Ellenwood Broncheau Wheeler Paisano III Mitchell Treasurer Chaplain Chairman Member Vice-Chairman term: May 2023 term: May 2022 term: May 2022 term: May 2021 term: May 2023 FRONT ROW Elizabeth Mary Jane Rachel Shirley J. Arthur-Attao Miles Edwards Allman Asst, Sec/Treasurer Member Secretary Member term: May 2023 term: May 2021 term: May 2023 term: May 2021 3 NPTEC meet with the US Army National Guard who were on the reservation to assist with the covid vacci- nation efforts. 4 Executive Direction Incident Commander, Antone, and Public Information Office, Scott, wearing donated face masks from Tim Weber. 5 EXECUTIVE The Executive Director’s Office manages the intergovernmental DIRECTOR’S affairs of the Nez Perce Tribe. This includes a major role in the pro- OFFICE tection and management of treaty resources, providing and improv- Jesse Leighton ing services in education, and delivering quality services to those in 208.843.7324 need. The role of the Executive Director also includes providing a safe environment for employees to work and the ability for employ- ees to accomplish the goals set by the NPTEC. Among many other routine tasks and special projects, this work also includes programs such as: Limited Liability Company (LLC) Certification. Title 12-1 of the Nez Perce Tribal Code, authorizes the organization of LLC companies through the Nez Perce Tribe. Non-Profit Corporation Certification. Title 12-2 of the Nez Perce Tribal Code, authorizes the organization of non-profit corporations through the Nez Perce Tribe. -

Nez Perce National Historical Park National Park Service Nez Perce Idaho, Washington, Oregon, and Montana U.S

Nez Perce National Historical Park National Park Service Nez Perce Idaho, Washington, Oregon, and Montana U.S. Department of the Interior The way we were taught is that we are part of Mother Earth. We’re brothers and sisters to the animals, we’re living in harmony with them. From the birds to the fish to the smallest insect. Herman Reuben A Park About a People, for All People Long before Meriwether Lewis and William and the history of the Nez Perce and their Chief Joseph’s band lived in the Wallo wa Lewis and Clark emerged from the moun- atrocities helped to bring on a war in 1877 These are only a few of the sites comprising Clark ventured west; before the English interaction with others. This in cludes other Valley in northeast Oregon. The Old Chief tains on the Weippe Prairie, and came upon be tween the Nez Perce and the US gov- Nez Perce Na tional Historical Park. An auto es tablished a colony at James town; before Indian peoples as well as the explorers, fur Joseph Gravesite is located outside the the Nimiipuu at a site three miles outside the ernment. The first battle of that war was tour of the entire park is more than 1,000 Christopher Colum bus stumbled upon the traders, missionaries, soldiers, settlers, gold town of Joseph at the edge of Wallowa town of Weippe. Along the Clear water River, fought in June 1877 in White Bird Canyon miles in length. The map below shows all 38 “new world,” the Nez Perce, who called miners, loggers, and farmers who moved Lake. -

Page 1 Volume 3 / Issue 1 Wilúupup | January NMPH COVID-19 Vaccine

Lapwai Girls NPTEC NMPH Win Holiday Letter COVID-19 Tournament to Joe Biden Vaccine Pages 6 & 7 Page 10 Page 12 NIMIIPUU TRIBAL TRIBUNE Wilúupup | January Volume 3 / Issue 1 Scott, Souther Named the Nez Perce Tribe Elders of the Year Nez Perce Tribe’s By Kathy Hedberg, lems and Scott Water Rights Lewiston Tribune said she has Administration Two Nez received “ex- Perce Tribe elders cellent care” Code Approved by who have devoted from her family the U.S. Department their lives to the and caregivers. of the Interior good of their peo- “She’s ple were honored been my guid- Lapwai, Idaho – On this week by the ing light,” Scott December 16, 2020, the tribe’s senior advi- said of his wife. U.S. Department of the In- sory board and sen- “She’s been terior (Interior) approved ior citizens center. my chief all my the Nez Perce Tribal Water Wilfred life. Every place Rights Administration Code “Scotty” Scott, we’ve been, after completing its required 89, and Mary she’s been there review. Assistant Secre- Jane “Tootsie” Wilfred “Scotty” Scott, 89, & Mary Jane “Tootsie” Souther, 84, were named the with me. Right tary for Indian Affairs Tara Souther, 84, were Nez Perce Tribe male and female Elders of the Year. (Photo: Nez Perce Tribe) now we’re hav- Sweeney, contacted Nez named the Nez ing a tough Perce Tribal Executive Com- Perce Tribe male and female visory Committee Treasurer, time, but it’s going to be OK.” mittee (NPTEC) Chairman, Elders of the Year on Tues- for his “willing heart for eve- Souther, who said she Shannon Wheeler personally day. -

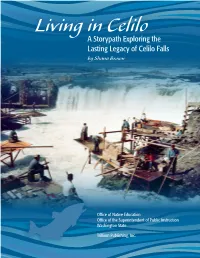

A Storypath Exploring the Lasting Legacy of Celilo Falls by Shana Brown

Living in Celilo A Storypath Exploring the Lasting Legacy of Celilo Falls by Shana Brown Office of Native Education Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction Washington State Trillium Publishing, Inc. Acknowledgements Contents Shana Brown would like to thank: Carol Craig, Yakama Elder, writer, and historian, for her photos of Celilo as well as her Introduction to Storypath ..................... 2 expertise and her children’s story “I Wish I Had Seen the Falls.” Chucky is really her first grandson (and my cousin!). Episode 1: Creating the Setting ...............22 The Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission for providing information about their organization and granting permission to use articles, including a piece from their Episode 2: Creating the Characters............42 magazine Wana Chinook Tymoo. Episode 3: Building Context ..................54 HistoryLink.org for granting permission to use the article “Dorothea Nordstrand Recalls Old Celilo Falls.” Episode 4: Authorizing the Dam ..............68 The Northwest Power and Conservation Council for granting permission to use an excerpt from the article “Celilo Falls.” Episode 5: Negotiations .....................86 Ritchie Graves, Chief of the NW Region Hydropower Division’s FCRPS Branch, NOAA Fisheries, for providing information on survival rates of salmon through the Episode 6: Broken Promises ................118 dams on the Columbia River system. Episode 7: Inundation .....................142 Sally Thompson, PhD., for granting permission to use her articles. Se-Ah-Dom Edmo, Shoshone-Bannock/Nez Perce/ Yakama, Coordinator of the Classroom-Based Assessment ...............154 Indigenous Ways of Knowing Program at Lewis & Clark College, Columbia River Board Member, and Vice President of the Oregon Indian Education Association, for providing invaluable feedback and guidance as well as copies of the actual notes and letters from the Celilo Falls Community Club. -

Oregon's History

Oregon’s History: People of the Northwest in the Land of Eden Oregon’s History: People of the Northwest in the Land of Eden ATHANASIOS MICHAELS Oregon’s History: People of the Northwest in the Land of Eden by Athanasios Michaels is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. Contents Introduction 1 1. Origins: Indigenous Inhabitants and Landscapes 3 2. Curiosity, Commerce, Conquest, and Competition: 12 Fur Trade Empires and Discovery 3. Oregon Fever and Western Expansion: Manifest 36 Destiny in the Garden of Eden 4. Native Americans in the Land of Eden: An Elegy of 63 Early Statehood 5. Statehood: Constitutional Exclusions and the Civil 101 War 6. Oregon at the Turn of the Twentieth Century 137 7. The Dawn of the Civil Rights Movement and the 179 World Wars in Oregon 8. Cold War and Counterculture 231 9. End of the Twentieth Century and Beyond 265 Appendix 279 Preface Oregon’s History: People of the Northwest in the Land of Eden presents the people, places, and events of the state of Oregon from a humanist-driven perspective and recounts the struggles various peoples endured to achieve inclusion in the community. Its inspiration came from Carlos Schwantes historical survey, The Pacific Northwest: An Interpretive History which provides a glimpse of national events in American history through a regional approach. David Peterson Del Mar’s Oregon Promise: An Interpretive History has a similar approach as Schwantes, it is a reflective social and cultural history of the state’s diversity. The text offers a broad perspective of various ethnicities, political figures, and marginalized identities. -

NEZ PERCE ...Through the Big Hole, Horse Prairie and Lemhi Valleys -1877

Auto Tour the plight op The NEZ PERCE ...through the Big Hole, Horse Prairie and Lemhi Valleys -1877 United States Forest Beaverhead-Deerlodge Department of Service National Agriculture Forest n August 1877, the tranquility of the Big Hole Valley was shattered by the sound of gunfire as a battle erupted between J five bands of Nez Perce Indians and U.S. military forces along the banks of the Big Hole River. For valley settlers, anxiety turned to fear and concern as nearly 800 Nez Perce men, woman and children gathered their wounded and fled southward towards Skinner Meadows and the country beyond. Today, you can retrace the route used by the Nez Perce and their military pursuers. This brochure describes the Nez Perce (Nee- Me-Poo) National Historic Trail between Big Hole National Batttlefield, Montana and Leadore, Idaho. The map shows the auto tour route in detail. Auto Tour Route - This designated auto route stays on all-weather roads and allows you to experience the Nez Perce Trail from a distance. The auto tour route is passable for all types of vehicles. An alternative route exists from Lost Trail Pass on the Montana/Idaho border south to Salmon and Leadore, Idaho along Hwy. 93 and 28. Adventure Route - For those seeking the most authentic historic route, a rough two lane road, connects Jackson, Montana and the Horse Prairie Valley. Examine the map carefully and watch for signs. You may want to take a more detailed Forest Map. The adventure route is usually passable from July to October. It is not recommended for motor homes or vehicles towing trailers. -

Origin of the Tucannon Phase in Lower Snake River Prehistory

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Steven W. Lucas for the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies in Anthropology, Anthropology, and Geography presented on September 29, 1994. Title: The Origin of the Tucannon Phase in Lower Snake River Prehistory. Abstract approved: Redacted for Privacy David R. Brauner Approximately 5,500 years ago a discreet period of wetter and cooler environmental conditions prevailed across the southern Columbia Plateau. This period was marked by the first prominent episodes of erosion to occur along the lower Snake River following the height of the Altithermal and eruption of Mt. Mazama during the mid post-glacial. In addition to the reactivation of small stream courses choked with debris and sediment, large stream channels began downcutting and scouring older terrace faces incorporated with large accumulations of Mazama ash. The resulting degradation of aquatic habitats forced concurrent changes within human economies adapted to the local riverine-environments. These adjustments reported for the Tucannon phase time period along the lower Snake River are notable and demonstrate the degree to which Cascade phase culture was unsuccessful in coping with environmental instability at the end of the Altithermal time period. This successionary event has demonstratively become the most significant post-glacial, qualitative change to occur in the lifeways of lower Snake River people prior to Euro-American influence. © Copyright by Steven W. Lucas September 29, 1994 All Rights Reserved Origin of the Tucannon Phase in Lower Snake River Prehistory By Steven W. Lucas A THESIS Submitted to Oregon State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies Completed September 29, 1994 Commencement June 1995 Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies thesis of Steven W. -

Pacific Northwest History and Cultures

Pacific Northwest History and Cultures Why Do the Foods We Eat Matter? Additional Resources This list provides supplementary materials for further study about the histories, cultures, and contemporary lives of Pacific Northwest Native Nations. Websites Affiliated Tribes of Northwest Indians (ATNI). Accessed February 7, 2017. http://www.atnitribes.org “Boldt at 40: A Day of Perspectives on the Boldt Decision.” Video Recordings. Salmon Defense. http://www.salmondefense.org Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), U.S. Department of the Interior. Last modified February 6, 2017. https://www.bia.gov Bureau of Indian Education (BIE). Last modified February 7, 2016. https://www.bie.edu Center for Columbia River History Oral History Collection. Last modified 2003. The Oregon Historical Society has a collection of analog audiotapes to listen to onsite; some transcripts are available. Here is a list of the tapes that address issues at Celilo and Celilo Village, both past and present: http://nwda.orbiscascade.org/ark:/80444/xv99870/op=fstyle.aspx?t=k&q=celilo#8. Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission (CRITFC). Accessed February 7, 2017. http://www.critfc.org/. Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission for Kids. Accessed February 7, 2017. http://www.critfc.org/for-kids-home/for-kids/. Cooper, Vanessa. Lummi Traditional Food Project. Northwest Indian College. Accessed February 7, 2017. http://www.nwic.edu/lummi-traditional-food-project/ Governor’s Office of Indian Affairs (GOIA, State of Washington). Accessed February 7, 2017. http://www.goia.wa.gov Makah Nation: A Whaling People. NWIFC Access. Accessed February 7, 2017. http://access.nwifc.org/newsinfo/streaming.asp National Congress of American Indians (NCAI). -

Native American Cultures, 1500 CE 165˚W 135˚W 105˚W 75˚W 45˚W

Native American Cultures, 1500 CE 165˚W 135˚W 105˚W 75˚W 45˚W Inupiaq 60˚N Yup’ik Aleut Athabascan Gwich’in Inuvialuit Alutiiq Chugach Hare Han Dogrib Inuit Gulf Tutchone of Alaska Kaska Inuit Tlingit Tahltan Slave Hudson Nisga’a Denesuline Bay Tsimshian Naskapi Halda Chilcotin Innu Beothuk Haisla Cree (Montagnais) Heiltsuk Shuswap Cree Kwakwaka’wakw 45˚N Nuu-chah-nulth Blackfoot Anishinaabe Mi’kmaq Lummi Atikamekw Maliseet Pacific Makah Salish Passamaquoddy Ocean Chinook Yakama Assiniboine Algonquian Penobscot Nez Perce Abenaki Siletz Mandan Ottawa Huron Massachuset Siuslaw UmatillaFlathead Ojibwa Umpqua Crow Hidatsa Sauk Haudenosaunee Wampanoag Yurok Paiute Cheyenne Menominee Lenape Narraganset Hupa Klamath Fox Potawatomi Lakota Dakota Erie Susquehannock Culture Areas Wintu Modoc Comanche (Sioux) Miami Pomo Shoshone Ute Arapaho Ofo Powhatan Arctic Miwok Pawnee Illini Atlantic Yokut Querechos Shawnee Paiute Dine Tamaroa Tuscarora Subarctic Salinan Hopi Ocean Chumash (Navajo) Osage Akimel Kiowa Cherokee Plains Luiseño Pueblo Yamasee 30˚N O’odham Wichita Chickasaw Tohono Zuni Cheraw Eastern Woodlands O’odham Tunica Congaree Opata Apache Caddo Choctaw Creek Cochimi Southwest Natchez Timucua Concho Houma Ais Yaqui Southeast Rarámuri CalusaTequesta Coahuiltec Gulf of Great Basin Mexico Tro pic of Ciboney Cancer Taino Arawak Northwest Coast Wixárika Tamaulipec Chichimecas Plateau Purépecha AZTEC 15˚N California EMPIRE Maya Caribbean Mixtec Sea Mesoamerica N Zapotec Mosquito Pipil Lenca Caribbean 0 1000 mi 0 1500 km This map is a representation of Native American groups starting from the time of European contact around 1500 CE, and for a period thereafter. It is not comprehensive, and those nations shown may have grown, diminished, or changed location over time.. -

Nez Perce National Historic Trail Map Tearsheet

Ask Us About Our “Experience the Nez Perce Trail” Auto Tour Brochures The Trail is sacred ground; please respect the resources during your travels. R1-19-11 Revised March 2019 Nez Perce (NEE-ME-POO) National Historic Trail ince aiding the Lewis and Clark expedition in 1805, The 1863 Treaty divided the tribe and foreshadowed a days – or the army would involvement in it whatsoever. In July of 1877, Tim’íne only 40 miles from Canada. Swhites knew the Nez Perce Indians as friends. The war whose repercussions are still felt. make them comply, by force. ’ilp’ílpnim (Chief Redheart’s) band and other Nez Piyóop’yoo ay áy (Chief Nez Perce (in their language, Niimíipuu, meaning The chiefs argued the time Perce returned from a buffalo hunt in Montana to White Bird) led a group “the people”) lived in bands, welcoming traders and For some years non-treaty Nez was inadequate to gather discover their homeland embroiled in conflict. All 33 of nearly 300 Nez Perce to missionaries to a land framed by the rivers, mountains, Perce continued to live in the the people and their horses men, women and children were transported to Fort safety in Canada, where they prairies, and valleys of present day southeastern Wallowas and other locations and cattle, and asked for an Vancouver, WA, where they were held at the military joined Chief Sitting Bull. Washington, northeastern Oregon, and north central within traditional homelands. extension, which Howard stockade until April 1878, when they were finally Idaho. They moved throughout the region including But conflict with newcomers brusquely refused.