The Anti-Black, Islamophobic Dimensions of CVE Surveillance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AKA Clark Kent) Middle Name Is Joseph

Superman’s (AKA Clark Kent) Middle Name Is Joseph. What’s that?! There in the sky? Is it a bird? Is it a plane? No! It’s the Man of Tomorrow! Superman has gone by many names over the years, but one thing has remained the same. He has always stood for what’s best about humanity, all of our potential for terrible destructive acts, but also our choice to not act on the level of destruction we could wreak. Superman was first created in 1933 by Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel, the writer and artist respectively. His first appearance was in Action Comics #1, and that was the beginning of a long and illustrious career for the Man of Steel. In his unmistakable blue suit with red cape, and the stylized red S on his chest, the figure of Superman has become one of the most recognizable in the world. The original Superman character was a bald telepathic villain that was focused on world domination. It was like a mix of Lex Luthor and Professor X. Superman’s powers include incredible strength, the ability to fly. X-ray vision, super speed, invulnerability to most attacks, super hearing, and super breath. He is nearly unstoppable. However, Superman does have one weakness, Kryptonite. When exposed to this radioactive element from his home planet, he becomes weak and helpless. Superman’s alter ego is mild-mannered reporter Clark Kent. He lives in the city of Metropolis and works for the newspaper the Daily Planet. Clark is in love with fellow reporter Lois Lane. -

Superman Ebook, Epub

SUPERMAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jerry Siegel | 144 pages | 30 Jun 2009 | DC Comics | 9781401222581 | English | New York, NY, United States Superman PDF Book The next event occurs when Superman travels to Mars to help a group of astronauts battle Metalek, an alien machine bent on recreating its home world. He was voiced in all the incarnations of the Super Friends by Danny Dark. He is happily married with kids and good relations with everyone but his father, Jor-EL. American photographer Richard Avedon was best known for his work in the fashion world and for his minimalist, large-scale character-revealing portraits. As an adult, he moves to the bustling City of Tomorrow, Metropolis, becoming a field reporter for the Daily Planet newspaper, and donning the identity of Superman. Superwoman Earth 11 Justice Guild. James Denton All-Star Superman Superman then became accepted as a hero in both Metropolis and the world over. Raised by kindly farmers Jonathan and Martha Kent, young Clark discovers the source of his superhuman powers and moves to Metropolis to fight evil. Superman Earth -1 The Devastator. The next few days are not easy for Clark, as he is fired from the Daily Planet by an angry Perry, who felt betrayed that Clark kept such an important secret from him. Golden Age Superman is designated as an Earth-2 inhabitant. You must be a registered user to use the IMDb rating plugin. Filming on the series began in the fall. He tells Atom he is welcome to stay while Atom searches for the people he loves. -

“I Am the Villain of This Story!”: the Development of the Sympathetic Supervillain

“I Am The Villain of This Story!”: The Development of The Sympathetic Supervillain by Leah Rae Smith, B.A. A Thesis In English Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved Dr. Wyatt Phillips Chair of the Committee Dr. Fareed Ben-Youssef Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School May, 2021 Copyright 2021, Leah Rae Smith Texas Tech University, Leah Rae Smith, May 2021 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to share my gratitude to Dr. Wyatt Phillips and Dr. Fareed Ben- Youssef for their tutelage and insight on this project. Without their dedication and patience, this paper would not have come to fruition. ii Texas Tech University, Leah Rae Smith, May 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………………….ii ABSTRACT………………………………………………………………………...iv I: INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………….1 II. “IT’S PERSONAL” (THE GOLDEN AGE)………………………………….19 III. “FUELED BY HATE” (THE SILVER AGE)………………………………31 IV. "I KNOW WHAT'S BEST" (THE BRONZE AND DARK AGES) . 42 V. "FORGIVENESS IS DIVINE" (THE MODERN AGE) …………………………………………………………………………..62 CONCLUSION ……………………………………………………………………76 BIBLIOGRAPHY …………………………………………………………………82 iii Texas Tech University, Leah Rae Smith, May 2021 ABSTRACT The superhero genre of comics began in the late 1930s, with the superhero growing to become a pop cultural icon and a multibillion-dollar industry encompassing comics, films, television, and merchandise among other media formats. Superman, Spider-Man, Wonder Woman, and their colleagues have become household names with a fanbase spanning multiple generations. However, while the genre is called “superhero”, these are not the only costume clad characters from this genre that have become a phenomenon. -

Superman 56+ 25/7/06 11:50 AM Page 56

final_superman_56+ 25/7/06 11:50 AM Page 56 FACT FILE SUPERMAN: the facts Name: Earth name – Clark Kent Krypton name – Kal-El Also known as The Man of Steel Born: on the planet Krypton Lives: in the city of Metropolis, and at the Fortress of Solitude in the Arctic Special powers: ● Can fly ● Can run at superspeed ● Can jump over high buildings ● Has superstrength: can lift cars and houses ● Can see through things ● Can heat things with his eyes Equipment: only his red and blue suit Weakness: kryptonite takes away his strength. Only the Earth’s sun can return it. Superman Enemy: Lex Luthor came to Earth Loves: Lois Lane from the planet Krypton. His father, Jor- El, knew there would be an explosion so he put his son Kal-El in a spaceship and sent him to Earth. The spaceship landed in the town of Smallville. The people who found him, Jonathan and Martha Kent, became his Earth parents. They called him Clark. As Clark got older, it became clear that he was very special… What do these words mean? You can use a dictionary. power strength energy breathe gravity hormones emergency 56 final_superman_56+ 25/7/06 11:51 AM Page 57 TheThe SCIENCESCIENCE ofof SupermanSuperman Of course, Krypton isn’t a real planet, and kryptonite doesn’t exist – luckily! But we do know some things about the science behind Superman. Q: Why is Superman so strong? A: Superman’s strength comes from Earth’s yellow sun which gives him his powers. The sun won’t give us superstrength, of course, but it gives us life. -

Justice League: Rise of the Manhunters

JUSTICE LEAGUE: RISE OF THE MANHUNTERS ABDULNASIR IMAM E-mail: [email protected] Twitter: @trapoet DISCLAIMER: I DON’T OWN THE RIGHTS TO THE MAJORITY, IF NOT ALL THE CHARACTERS USED IN THIS SCRIPT. COMMENT: Although not initially intended to, this script is also a response to David Goyer who believed you couldn’t use the character of the Martian Manhunter in a Justice League movie, because he wouldn’t fit. SUCK IT, GOYER! LOL! EXT. SPACE TOMAR-RE (V.O) Billions of years ago, when the Martians refused to serve as the Guardians’ intergalactic police force, the elders of Oa created a sentinel army based on the Martian race… they named them Manhunters. INSERT: MANHUNTERS TOMAR-RE (V.O) At first the Manhunters served diligently, maintaining law and order across the universe, until one day they began to resent their masters. A war broke out between the two forces with the Guardians winning and banishing the Manhunters across the universe, stripping them of whatever power they had left. Some of the Manhunters found their way to earth upon which entering our atmosphere they lost any and all remaining power. As centuries went by man began to unearth some of these sentinels, using their advance technology to build empires on land… and even in the sea. INSERT: ATLANTIS EXT. THE HIMALAYANS SUPERIMPOSED: PRESENT INT. A TEMPLE DESMOND SHAW walks in. Like the other occupants of the temple he’s dressed in a red and blue robe. He walks to a shadowy figure. THE GRANDMASTER (O.S) It is time… prepare the awakening! Desmond Shaw bows. -

What Superman Teaches Us About the American Dream and Changing Values Within the United States

TRUTH, JUSTICE, AND THE AMERICAN WAY: WHAT SUPERMAN TEACHES US ABOUT THE AMERICAN DREAM AND CHANGING VALUES WITHIN THE UNITED STATES Lauren N. Karp AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Lauren N. Karp for the degree of Master of Arts in English presented on June 4, 2009 . Title: Truth, Justice, and the American Way: What Superman Teaches Us about the American Dream and Changing Values within the United States Abstract approved: ____________________________________________________________________ Evan Gottlieb This thesis is a study of the changes in the cultural definition of the American Dream. I have chosen to use Superman comics, from 1938 to the present day, as litmus tests for how we have societally interpreted our ideas of “success” and the “American Way.” This work is primarily a study in culture and social changes, using close reading of comic books to supply evidence. I argue that we can find three distinct periods where the definition of the American Dream has changed significantly—and the identity of Superman with it. I also hypothesize that we are entering an era with an entirely new definition of the American Dream, and thus Superman must similarly change to meet this new definition. Truth, Justice, and the American Way: What Superman Teaches Us about the American Dream and Changing Values within the United States by Lauren N. Karp A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Presented June 4, 2009 Commencement June 2010 Master of Arts thesis of Lauren N. Karp presented on June 4, 2009 APPROVED: ____________________________________________________________________ Major Professor, representing English ____________________________________________________________________ Chair of the Department of English ____________________________________________________________________ Dean of the Graduate School I understand that my thesis will become part of the permanent collection of Oregon State University libraries. -

Superman: Darkseid Rising

Superman: Darkseid Rising Based on "Superman" created by Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster and characters appearing in DC Comics Screenplay by Derek Anderson Derek Anderson (949)933-6999 [email protected] SUPERMAN: DARKSEID RISING Story by Larry Gomez and Derek Anderson Screenplay by Derek Anderson EXT. KENT FARM - NIGHT We pan over the Kent Farm, closing in on a barn. A soft BLUE GLOW emanates from within. INT. KENT BARN - NIGHT Inside the barn, underneath the FLOORBOARDS, the glow FLASHES BRIGHTLY. A ROBOTIC VOICE is heard speaking in an unknown language. FLASHBACK INT. KRYPTON - JOR-EL'S LAB - NIGHT KAL-EL'S POV BABY KAL-EL sits in a makeshift ROCKET, somewhat crude, but sturdy. JOR-EL is talking to Kal-El, but we cannot understand him. He is speaking in Kryptonian. The building shakes, CRYSTALLINE STRUCTURES collapse around. Jor-El walks away from us, holding his wife's hand as they move to a CONTROL PANEL. Behind Jor-El, a ROBOT with blue eyes, standing as tall as a man, enters the launching bay of Jor-El's lab. A robotic voice speaks. Baby Kal-El reaches out for the robot as it walks close to Jor-El's rocket. It transforms into a SMALL SIZED ROCKET with a BLUE EGG-SHAPED NOSE CONE. EXT. OUTER SPACE The rocket ship fires away from Krypton as it EXPLODES into shards of DUST and CRYSTAL. INT. ROCKET SHIP Kal-El sleeps as the rocket increases to hyper speed. Within the craft, a soft BLUE LIGHT grows brighter, illuminating Kal-el. -

The Best Day of Lois Lane's Life by Dandello (AKA Librarian) © 27-Sep-09 Rating: K+ Disclaimer: All Publicly Recognizable Characters, Settings, Etc

The Best Day of Lois Lane's Life by Dandello (AKA Librarian) © 27-Sep-09 Rating: K+ Disclaimer: All publicly recognizable characters, settings, etc. are the property of their respective owners. The original characters and plot are the property of the author. The author is in no way associated with the owners, creators, or producers of any media franchise. No copyright infringement is intended. Lois Lane read the letter once again - she'd read it so often in the past two weeks she had it memorized. The paper was wilting around the edges but she couldn't help it. It was as though she was afraid the words would change if she didn't keep an eye on them. 'You have been invited to interview for a position at the Daily Planet...' It didn't matter that the position was for a summer intern - the Daily Planet only had three such positions per year and even getting the invitation to apply was an incredible honor. But Lois wanted more than just the honor of the invitation. She wanted - had been working on earning - a job in the newsroom. Even sweeping the floor at a place as hallowed in journalistic history as the Daily Planet would be acceptable - okay, maybe not sweeping the floors, but anything else would be fine by her - anything to just get her foot in the door. Her grades were excellent - she'd been on the president's list every semester so far. Her portfolio and references were also excellent. She had already won several awards for her writing and her dorm-mate's personal betrayal and the theft of one of her articles, while infuriating, had done nothing to keep her from being at the top of her class. -

Activity Kit

Activity Kit Copyright (c) 2011 DC Comics. All related characters and elements are trademarks of and (c) DC Comics. (s11) ACTIvITy KIT wORD SCRAMBLE Help Batman solve a mystery by unscrambling the following words! Nermusap __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ Barrzio __ __ __ __ __ __ __ Matbna __ __ __ __ __ __ Eth Kojre __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ Redwon Waomn Wactnamo __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ Raincaib __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ Neerg Nerltan Hheecat __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ Ssrtonie __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ Eht Shafl __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ Slirev Naws __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ Quamnaa __ __ __ __ __ __ __ Hte Ylaid Neplta __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ Slio Anle __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ Msliporote __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ Nibor __ __ __ __ __ Maghto Ycti __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ Ptknory __ __ __ __ __ __ __ Zamona __ __ __ __ __ __ Vacbtae __ __ __ __ __ __ __ Repow grin __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ Elx Ultroh __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ Copyright (c) 2011 DC Comics. -

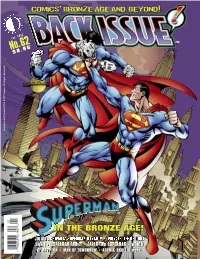

IN the BRONZE AGE! BRONZE the in , Bronze AGE and Beyond and AGE Bronze I

Superman and Bizarro TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. 0 1 No.62 Feb. 201 3 $ 8 . 9 5 1 82658 27762 8 COMiCs JULIUS SCHWARTZ SUPERMAN DYNASTY • PRIVATE LIFE OF CURT SWAN • SUPERMAN FAMILY • EARTH-TWO SUPERMAN • WORLD OF KRYPTON • MAN OF TOMORROW • ATOMIC SKULL & more! IN THE BRONZE AGE! , bROnzE AGE AnD bEYOnD i . Volume 1, Number 62 February 2013 Celebrating the Best ® Comics of the '70s, Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! '80s,'90s, and Beyond! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael “Don’t Call Me Chief!” Eury PUBLISHER John “Morgan Edge” Morrow DESIGNER Rich “Superman’s Pal” Fowlks COVER ARTISTS José Luis García-López and Scott Williams COVER COLORIST Glenn “Grew Up in Smallville” Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael “Last Son of Krypton” Kronenberg BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 A dedication to the man who made us believe he could fly, Christopher Reeve PROOFREADER Rob “Cub Reporter” Smentek FLASHBACK: The Julius Schwartz Superman Dynasty . .3 SPECIAL THANKS Looking back at the Super-editor(s) of the Bronze Age, with enough art to fill a Fortress! Murphy Anderson Dennis O’Neil SUPER SALUTE TO CARY BATES . .18 CapedWonder.com Luigi Novi/Wikimedia Cary Bates Commons SUPER SALUTE TO ELLIOT S! MAGGIN . .20 Kurt Busiek Jerry Ordway Tim Callahan Mike Page BACKSTAGE PASS: The Private Life of Curt Swan . .23 Howard Chaykin Mike Pigott Fans, friends, and family revisit the life and career of THE Superman artist Gerry Conway Al Plastino DC Comics Alex Ross FLASHBACK: Superman Calls for Back-up! . .38 Dial B for Blog Bob Rozakis The Man of Steel’s adventures in short stories Tom DeFalco Joe Rubinstein FLASHBACK: Superman Family Portraits . -

Examining the Regressive State of Comics Through DC Comics' Crisis on Infinite Earths

How to Cope with Crisis: Examining the Regressive State of Comics through DC Comics' Crisis on Infinite Earths Devon Lamonte Keyes Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Virginia Fowler, Chair James Vollmer Evan Lavender-Smith May 10, 2019 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Comics Studies, Narratology, Continuity Copyright 2019, Devon Lamonte Keyes How to Cope with Crisis: Examining the Regressive state of Comics through DC Comics' Crisis on Infinite Earths Devon Lamonte Keyes (ABSTRACT) The sudden and popular rise of comic book during the last decade has seen many new readers, filmgoers, and television watchers attempt to navigate the world of comics amid a staggering influx of content produced by both Marvel and DC Comics. This process of navigation is, of course, not without precedence: a similar phenomenon occurred during the 1980s in which new readers turned to the genre as superhero comics began to saturate the cultural consciousness after a long period of absence. And, just as was the case during that time, such a navigation can prove difficult as a veritable network of information|much of which is contradictory|vies for attention. How does one navigate a medium to which comic books, graphic novels, movies, television shows, and other supplementary forms all contribute? Such a task has, in the past, proven to be near insurmountable. DC Comics is no stranger to this predicament: during the second boom of superhero comics, it sought to untangle the canonical mess made by decades of overlapping history to the groundbreaking limited series Crisis on Infinite Earths, released to streamline its then collection of stories by essentially nullifying its previous canon and starting from scratch. -

USC Annenberg's Clark Kent, Lois Lane Expert Reviews Man of Steel

USC Annenberg’s Clark Kent, Lois Lane expert reviews Man of... http://news.usc.edu/#!/article/53033/usc-annenbergs-clark-kent-... USC News USC Annenberg’s Clark Kent, Lois Lane expert reviews Man of Steel By Jeremy Rosenberg July 10, 2013 With the latest Superman film, Man of Steel, raking in ticket sales, Jeremy Rosenberg decided to check in with USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism Professor Joe Saltzman. Saltzman, director of the Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture, a project of the Norman Lear Center, is an expert on all things Clark Kent, Lois Lane, Perry White and Daily Planet-related. The following contains spoilers. Jeremy Rosenberg: You weren’t planning to race out and see the film until we asked for your review. Are you glad you went? Joe Saltzman: The only good part of the film was the last few minutes when Clark Kent finally shows up at the Daily Planet to meet the staff and start work as a journalist. The rest of the film was a disaster — a dark, brooding, confusing, ridiculous action film that comes close to violating the Superman-Daily Planet mythology that has been so successful in the past. The comics, the radio series, the television series, the four Superman movies (1978-1987), Lois & Clark and especially Smallville and the various cartoon series got it right. Superman Returns was a disaster with bad writing and bad acting and a Lois Lane who was nothing like the Lois Lane of old. Man of Steel gets the characters right and they look the part — Amy Adams is a wonderful Lois Lane — but the gloomy photography and meaningless, loud action often filmed in confusing close-ups defy logic.