Quest of the Gran Quivira

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coronado and Aesop Fable and Violence on the Sixteenth-Century Plains

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for 2009 Coronado and Aesop Fable and Violence on the Sixteenth-Century Plains Daryl W. Palmer Regis University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Palmer, Daryl W., "Coronado and Aesop Fable and Violence on the Sixteenth-Century Plains" (2009). Great Plains Quarterly. 1203. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/1203 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. CORONADO AND AESOP FABLE AND VIOLENCE ON THE SIXTEENTH~CENTURY PLAINS DARYL W. PALMER In the spring of 1540, Francisco Vazquez de the killing of this guide for granted, the vio Coronado led an entrada from present-day lence was far from straightforward. Indeed, Mexico into the region we call New Mexico, the expeditionaries' actions were embedded where the expedition spent a violent winter in sixteenth-century Spanish culture, a milieu among pueblo peoples. The following year, that can still reward study by historians of the after a long march across the Great Plains, Great Plains. Working within this context, I Coronado led an elite group of his men north explore the ways in which Aesop, the classical into present-day Kansas where, among other master of the fable, may have informed the activities, they strangled their principal Indian Spaniards' actions on the Kansas plains. -

A Council Circle at Etzanoa? Multi-Sensor Drone Survey at an Ancestral Wichita Settlement in Southeastern Kansas

REPORTS A Council Circle at Etzanoa? Multi-sensor Drone Survey at an Ancestral Wichita Settlement in Southeastern Kansas Jesse Casana , Elise Jakoby Laugier, Austin Chad Hill, and Donald Blakeslee This article presents results of a multi-sensor drone survey at an ancestral Wichita archaeological site in southeastern Kansas, originally recorded in the 1930s and believed by some scholars to be the location of historical “Etzanoa,” a major settlement reportedly encountered by Spanish conquistador Juan de Oñate in 1601. We used high-resolution, drone-acquired thermal and multispectral (color and near-infrared) imagery, alongside publicly available lidar data and satellite imagery, to prospect for archaeological features across a relatively undisturbed 18 ha area of the site. Results reveal a feature that is best interpreted as the remains of a large, circular earthwork, similar to so-called council circles documented at five other contemporary sites of the Great Bend aspect cultural assemblage. We also located several features that may be remains of house basins, the size and configuration of which conform with historical evidence. These findings point to major investment in the construction of large- scale ritual, elite, or defensive structures, lending support to the interpretation of the cluster of Great Bend aspect sites in the lower Walnut River as a single, sprawling population center, as well as demonstrating the potential for thermal and multispec- tral surveys to reveal archaeological landscape features in the Great Plains and beyond. Keywords: remote sensing, thermography, UAV, Great Bend aspect, earthwork, ancestral Wichita Este artículo presenta los resultados de una encuesta de drones con sensores múltiples en un sitio arqueológico ancestral de Wichita en el sureste de Kansas, originalmente registrado en la década de 1930 y que muchos estudiosos creen que es la ubica- ción del histórico “Etzanoa”, un asentamiento importante que según los informes encontró el conquistador español Juan de Oñate en 1601. -

El Adelantado Juan De Oñate

álber vázquez El adelantado Juan de Oñate Y la búsqueda del reino perdido de Quivira TT_Adelantadojuanonate.indd_Adelantadojuanonate.indd 5 114/11/184/11/18 113:413:41 Palabras previas uando en 1605, de regreso del océano Pacífico, Juan de Oñate Catraviesa Nuevo México, se para a descansar en un paraje lla- mado El Morro y escribe el grafiti más antiguo que un blanco ha- ya dejado en Norteamérica: «Pasó por aquí el adelantado Juan de Oñate», se puede leer, y es una de las pocas veces en las que Oña- te escribe algo que es verdad. Oñate tiene una vida pública muy corta, de apenas doce años. Es el último de los grandes conquistadores españoles, una sa- ga de hombres a medio camino entre los exploradores ávidos de riqueza y los aventureros que buscan saber qué hay donde ningún blanco ha ido. Cuando esta vida da comienzo, Oñate es ya un hom- bre maduro, riquísimo y que goza de una posición social inmejo- rable. Entre otras cosas, se ha casado con una mujer que desciende directamente del mítico Hernán Cortés y del no menos legendario emperador Moctezuma. Y, sin embargo, decide subirse a un caballo y realizar proe- zas dignas de auténticos héroes sobrehumanos. El gran problema al que se enfrenta la historiografía es que, a pesar de que existen abundantes fuentes de información acerca de lo que hizo, mu- 9 TT_Adelantadojuanonate.indd_Adelantadojuanonate.indd 9 114/11/184/11/18 113:413:41 chas de ellas directas, todas resultan poco fiables. Oñate y sus hombres siempre van a sitios donde el agua es fresquísima, las bayas son deliciosas y los indios salen corriendo a recibirles con las manos llenas de regalos. -

Geology of the Gran Quivira Quadrangle, New Mexico

CONTENTS Page The New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources ------------------------ 6 Board of Regents _ ------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 Introduction --------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 7 Location of the area ----------------------------------------------------------------- 7 Topography ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- 9 Purpose and scope of the report ------------------------------------------------ 11 Previous work ----------------------------------------------------------------------- 12 Acknowledgments ------------------------------------------------------------------ 12 Ruins at Gran Quivira and Abo ------------------------------------------------- 12 Pre-Cambrian rocks --------------------------------------------------------------------- 13 Sedimentary rocks------------------------------------------------------------------------- 16 Pennsylvanian system ------------------------------------------------------------ 16 General statement ----------------------------------------------------------- 16 Sandia formation: upper member ---------------------------------------- 20 Definition ----------------------------------------------------------------- '20 Distribution -------------------------------------------------------------- 20 Character and thickness --------------------------------------------- 20 Fossils and correlation ------------------------------------------------ 21 Madera limestone ------------------------------------------------------------ -

Hydrogeomorphic Evaluation of Ecosystem Restoration and Management Options for Quivira National Wildlife Refuge

HYDROGEOMORPHIC EVALUATION OF ECOSYSTEM RESTORATION AND MANAGEMENT OPTIONS FOR QUIVIRA NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE Prepared For: U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 6 Denver, Colorado By: Mickey E. Heitmeyer, PhD Greenbrier Wetland Services Advance, MO Rachel A. Laubhan U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Quivira National Wildlife Refuge Stafford, KS Michael J. Artmann U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 6 Division of Planning Denver, CO Greenbrier Wetland Services Report 12-04 March 2012 Mickey E. Heitmeyer, PhD Greenbrier Wetland Services Route 2, Box 2735 Advance, MO 63730 www.GreenbrierWetland.com Publication No. 12-04 Suggested citation: Heitmeyer, M. E., R. A. Laubhan, and M. J. Artmann. 2012. Hydrogeomorphic evaluation of ecosystem restoration and management options for Quivira National Wildlife Refuge. Prepared for U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 6, Denver, CO. Greenbrier Wetland Services Report 12-04, Blue Heron Conservation Design and Printing LLC, Bloomfield, MO. Photo credits: Cover: Dan Severson, USFWS Rachel Laubhan, Dan Severson, Bob Gress, Cary Aloia (www.GardnersGallery.com) This publication printed on recycled paper by ii CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 1 THE HISTORICAL QUIVIRA ECOSYSTEM ..................................................... 5 Geology and Geomorphology ..................................................................... -

Spanish Relations with the Apache Nations East of the Rio Grande

SPANISH RELATIONS WITH THE APACHE NATIONS EAST OF THE RIO GRANDE Jeffrey D. Carlisle, B.S., M.A. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2001 APPROVED: Donald Chipman, Major Professor William Kamman, Committee Member Richard Lowe, Committee Member Marilyn Morris, Committee Member F. Todd Smith, Committee Member Andy Schoolmaster, Committee Member Richard Golden, Chair of the Department of History C. Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Carlisle, Jeffrey D., Spanish Relations with the Apache Nations East of the Río Grande. Doctor of Philosophy (History), May 2001, 391 pp., bibliography, 206 titles. This dissertation is a study of the Eastern Apache nations and their struggle to survive with their culture intact against numerous enemies intent on destroying them. It is a synthesis of published secondary and primary materials, supported with archival materials, primarily from the Béxar Archives. The Apaches living on the plains have suffered from a lack of a good comprehensive study, even though they played an important role in hindering Spanish expansion in the American Southwest. When the Spanish first encountered the Apaches they were living peacefully on the plains, although they occasionally raided nearby tribes. When the Spanish began settling in the Southwest they changed the dynamics of the region by introducing horses. The Apaches quickly adopted the animals into their culture and used them to dominate their neighbors. Apache power declined in the eighteenth century when their Caddoan enemies acquired guns from the French, and the powerful Comanches gained access to horses and began invading northern Apache territory. -

Gran Quivira: a Blending of Cultures in a Pueblo Indian Village

National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places U.S. Department of the Interior Gran Quivira: A Blending of Cultures in a Pueblo Indian Village Gran Quivira: A Blending of Cultures in a Pueblo Indian Village (National Park Service) At first, one encounters a soothing silence broken only by a constant breeze and the chirr of insect wings. Sparse desert flora partially hides the remains of ancient stone houses built by early American Indians who inhabited this area of central New Mexico. Farther along the trail an excavated mound reveals the broken foundations of a large apartment house and several ceremonial kivas typical of the southwest Pueblo Indian culture. Nearby, the ruins of two mission churches attest to the presence of Spanish priests in this isolated region. The quiet remnants of the village of Las Humanas, now called Gran Quivira, only hint at the vibrant society that thrived here until the late 17th century. Today it is one of three sites that make up Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument. National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places U.S. Department of the Interior Gran Quivira: A Blending of Cultures in a Pueblo Indian Village Document Contents National Curriculum Standards About This Lesson Getting Started: Inquiry Question Setting the Stage: Historical Context Locating the Site: Map 1. Map 1: Early Puebloan communities 2. Map 2: The Salinas Basin Determining the Facts: Readings 1. Reading 1: Village Life 2. Reading 2: The Coming of the Spaniards Visual Evidence: Images 1. Photo 1: Gran Quivira Unit, Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument 2. Photo 2: A kiva at Gran Quivira 3. -

KPMA04 Burgandy

From Coronado to Cattlemen Assessing the Legacy of 19th-Century Cattle Trails on the Southern High Plains he years following A.D. 1250 witnessed the intensification of Ttrade among Native American villagers on the southern High Plains. Though their economic interaction is certain, archeologists’ ability to map the pathways that linked these Plains horticulturalists is incomplete—isolated to a series of east-west routes that connected the southwestern Pueblos with the Plains and Mississippian trade networks (Kelly 1955; Vehik 1986). The occurrence in Plains villages of artifacts made out of certain kinds of stone from source locations to the north and south confirms that the north-south movement of peoples and technology was an important aspect of the economy; however, the corridors favored for such traffic are yet to be discovered. Beyond the southern High Plains, archeologists are assured that a vast network of roads linked trade centers of pre-Columbian America. This web of highways was first mentioned in the written accounts of early European explorers. Later, archeologists confirmed trail locations by identifying a series of Native American town sites containing significant quantities of non-local materials (Ewers 1954; O’Brien 1986; Riley 1976; Wood 1980, 1983). Our approach is the same. This article reports on the use of published historic documents to locate a possible prehistoric north-south route on the southern High Plains. Subsequent field research, including archeological survey and geomorphological studies, attempted Figure 1. Late Prehistoric and Protohistoric cultural complexes. to substantiate claims that nineteenth- century cattle trails previously were used by prehistoric groups who occupied the Trade on the consisted primarily of hunting supple- southern High Plains. -

Gran Quiviragordon Vivian

EXCAVATIONS I N A 17TH-CENTURY JUMANO PUEBLO GRAN QUIVIRA GORDON VIVIAN WITH A CHAPTER ON ARTIFACTS FROM GRAN QUlVlRA SALLIE VAN VALKENBURGH ARCHEOLOGICAL RESEARCH SERIES NUMBER EIGHT NATIONAL PARK SERVICE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Stewart L. Udall, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE George B. Hartzog, Jr., Director America's Natural Resources Created in 1849, the Department of the Interior–America's Department of Natural Resources– is concerned with the management, conservation, and de- velopment of the Nation's water, wildlife, mineral, forest, and park and recre- ational resources. It also has major responsibilities for Indian and territorial affairs. As the Nation's principal conservation agency, the Departmentworks to as- sure that nonrenewable resources are developed and used wisely, that park and recreational resources are conserved, and that renewable resources make their full contribution to the progress, prosperity, and security of the United States- now and in the future. Archeological Research Series No. 1. Archeology of the Bynum Mounds, Mississippi. No. 2. Archeological Excavations in Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, 1950. No. 3. Archeology of the Funeral Mound, Ocmulgee National Monument, Georgia. No. 4. Archeological Excavations at Jamestown, Virginia. No. 5. The Hubbard Site and Other Tri-wall Structures in New Mexico and Colorado. No. 6. Search for the Cittie of Ralegh, Archeological Excavations at Fort Ralegh National Historic Site, North Carolina. No. 7. The Archeological Survey of Wetherill Mesa, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado. No. 8. Excavations in a 17th-century Jumano Pueblo, Gran Quivira, New Mexico. THIS PUBLICATION is one of a series of research studies devoted to specialized topics which have been explored in connection with the various areas in the National Park System. -

Journal of the House

606 JOURNAL OF THE HOUSE Journal of the House FIFTY-FIFTH DAY HALL OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, TOPEKA, KS, Wednesday, April 5, 2017, 10:00 a.m. The House met pursuant to adjournment with Speaker Ryckman in the chair. The roll was called with 125 members present. Prayer by Chaplain Brubaker: Creator God, We have noticed in the last few weeks how Spring has struggled to establish itself, warm and sunny one week, the last few days gloomy with dark skies and rain. Perhaps the same could be said about inside the chamber… one day decisions have been made that brighten their hopes, the next day, decisions made that cause some to feel as gray and gloomy as the sky. Today, Lord, I ask for discernment and clarity as they judge anew their adherence to principle, conviction, and commitment. Give them the ability to listen to one another and work cooperatively to solve the important issue of the day. Heal that which is broken— restore relationships that are separated by party lines— surprise the cynical—humble the exalted— and awaken the exhausted. In Your Name I pray, Amen. The Pledge of Allegiance was led by Rep. Sloan. INTRODUCTION OF GUESTS There being no objection, the following remarks of Rep. Claeys are spread upon the Journal: It is an honor to stand here today with the principal, coaches and students from my alma mater, Sacred Heart High School in Salina. With me at the well this morning are the members of the Knights Boys Basketball team. APRIL 5, 2017 607 Head Coach, Pat Martin; Assistant, Ashton Richards; Seniors, Quinn Riordan, Stratton Brown, Jake Brull and Zach Gaskill and starters, Trace Leners and Caleb Jordan. -

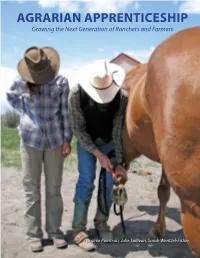

Agrarian Apprentice LR

AGRARIAN APPRENTICESHIP Growing the Next Generation of Ranchers and Farmers Virginie Pointeau, Julie Sullivan, Sarah Wentzel-Fisher NAP’s very first apprentice Amber Reed learning about horse care from Michael Bain, expert horseman, ranch manager, and Quivira Coalition board member. San Juan Ranch, 2009. Photo by Avery C. Anderson Sponholtz. The New Agrarian Program AGRARIAN APPRENTICESHIP Growing the Next Generation of Ranchers and Farmers Virginie Pointeau, Julie Sullivan, Sarah Wentzel-Fisher Quivira Coalition · Santa Fe, New Mexico Designed by Sarah Wentzel-Fisher Funded by The Thornburg Foundation Published by the Quivira Coalition 1413 Second Street, Suite 1, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87505 TEXT This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution — ShareAlike 4.0 International License (creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/). You are free to: Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format; Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially. The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms. Under the following terms: Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.; ShareAlike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original.; No additional restrictions — You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits. Notices: You do not have to comply with the license for elements of the material in the public domain or where your use is permitted by an applicable exception or limitation. -

Archaeologists to Believe That Religion Was Instrumental to Cahokia’S Growth

THE CONSERVANCYBANNER BANNER PRESERVES BANNER ITS 500TH • BANNER SITE •BANNER ARTIFACTS BANNER FOR SALE • BANNER • CAHOKIA’S BANNER RELIGION american archaeologySPRING 2016 a quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancy Vol. 20 No. 1 The National Park Service: 100 Years Of Archaeology $3.95 $3.95 american archaeologySPRING 2016 a quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancy Vol. 20 No. 1 COVER FEATURE 32 CELEBRATING A CENTENNIAL BY MARGARET SHAKESPEARE The National Park Service has made significant contributions to archaeology during its 100-year existence. 12 ARTIFACTS FOR SALE BY JULIAN SMITH Selling ancient artifacts is commonplace for some people in western Alaska. 18 RELIGION AND THE RISE OF CAHOKIA BY ALEXANDRA WITZE Recent research at a neighboring site has led some archaeologists to believe that religion was instrumental to Cahokia’s growth. 26 SEARCHING FOR ETZANOA 32 NPS BY DAVID MALAKOFF Archaeologists in Kansas believe they have found one of North America’s largest prehistoric settlements. 39 FIVE HUNDRED AND COUNTING BY TAMARA STEWART The Archaeological Conservancy has preserved more than 500 sites since it was formed in 1980. 45 new acquisition PARTNERING FOR PRESERVATION The Conservancy joins forces with two organizations to establish another preserve. 46 new acquisition PRESERVING A LEGEND The Conservancy, government agencies, and a private landowner teram up to preserve all of Legend Rock. 48 point acquisition AUKETAT P A WEALTH OF CERAMICS Archaeologists don’t know who lived at LA 503, but they do know the residents used a wide variety of ceramics. TIMOTHY TIMOTHY 18 2 LAY OF THE LAND 50 FiELD NOTES 52 REVIEWS 54 EXPEDITIONS 3 LETTERS 5 EVENTS COVER: A kiva (foreground) and the remains of an 18th-century Spanish mission church 7 IN THE NEWS (background) are seen in this photo of Pecos • Southwest Native Depopulation Occurred Later Than Thought National Historical Park in Pecos, New Mexico.