Generate PDF of This Page

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Utopian Visions of Solidarity in Polish Cinema

Uniwersytet Gdaski University of Gdask https://repozytorium.bg.ug.edu. pl Publikacja / Utopian visions of solidarity in Polish cinema, Publication Przylipiak Mirosaw Adres publikacji w Repozytorium URL / https://repozytorium.bg.ug.edu.pl/info/article/UOGba124af879dd4dd9a5903fbe32544a4e/ Publication address in Repository Data opublikowania w 7 kwi 2020 Repozytorium / Deposited in Repository on Rodzaj licencji / Type Attribution (CC BY) of licence Cytuj t wersj / Przylipiak Mirosaw: Utopian visions of solidarity in Polish cinema, Beyond Philology: Cite this An International Journal of Linguistics, Literary Studies and English Language version Teaching, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Gdaskiego, no. 14/4, 2017, pp. 141-165 Beyond Philology No. 14/4, 2017 ISSN 1732-1220, eISSN 2451-1498 Utopian visions of solidarity in Polish cinema MIROSŁAW PRZYLIPIAK Received 11.10.2016, received in revised form 6.12.2017, accepted 11.12.2017. Abstract The “Solidarity” movement, especially in the first period of its activi- ty, that is, in the years 1980-1981, instigated numerous myths. Polish cinema contributed immensely to their creation and prolifera- tion. The most important among those myths were: the myth of soli- darity between all working people, the myth of solidarity between the genders, and – perhaps the most lasting of all – the myth of the alli- ance between workers and intellectuals. All these forms of solidarity really existed for a short period of time in 1980/1981, but each of them collapsed afterwards. Consequently, one can say that they bore -

Please Download Issue 1-2 2015 Here

B A L A scholarly journal and news magazine. April 2015. Vol. VIII:1–2. From TIC the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES), Södertörn University. The story of Papusza, W a Polish Roma poet O RLDS A pril 2015. V ol. VIII BALTIC :1–2 WORLDSbalticworlds.com Special section Gender & post-Soviet discourses Special theme Voices on solidarity S pecial section: pecial Post- S oviet gender discourses. gender oviet Lost ideals, S pecial theme: pecial shaken V oices on solidarity solidarity on oices ground also in this issue Illustration: Karin Sunvisson RUS & MAGYARS / EsTONIA IN EXILE / DIPLOMACY DURING WWII / ANNA WALENTYNOWICZ / HIJAB FASHION Sponsored by the Foundation BALTIC for Baltic and East European Studies WORLDSbalticworlds.com in this issue editorial Times of disorientation he prefix “post-” in “post-Soviet” write in their introduction that “gender appears or “post-socialist Europe” indicates as a conjunction between the past and the pres- that there is a past from which one ent, where the established present seems not to seeks to depart. In this issue we will recognize the past, but at the same time eagerly Tdiscuss the more existential meaning of this re-enacts the past discourses of domination.” “departing”. What does it means to have all Another collection of shorter essays is con- that is rote, role, and rules — and seemingly nected to the concept of solidarity. Ludger self-evident — rejected and cast away? What Hagedorn has gathered together different Papusza. is it to lose the basis of your identity when the voices, all adding insights into the meaning of society of which you once were a part ceases solidarity. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1984, No.21

www.ukrweekly.com (ГОС Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association! > 3 w ax XJO– oo z -no - -n о OO-D о z m cua 33- м mo О ИО rainian Weekly tn СД — Vol. Lll No. 21 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, MAY 20, 1984 25c^t? Stepson fears Sakharov and wife Soviets to terminate contracts could die from hunger strikes with Western parcel companies WASHINGTON - The son of Ye– by George B. Zarycky the owner of the company never paid Іапа Bonner, wife of Andrei Sakharov, the Soviets millions of dollars in duties said on May 15 that the couple could JERSEY CITY, N.J. - The Soviet and other fees, forcing them to ship die soon unless the Soviet authorities Union has recently -implemented a back many parcels at their own expense. allowed his mother to leave the country, change in its policy on the shipment of But others see the Soviet decision in reported the Associated Press. parcels to the USSR that will make it political terms. According to spokes Dr. Sakharov has been on a hunger impossible, effective August 1, to send men from several small, Ukrainian strike for some 14 days to back his packages from the United States parcel companies, the Soviets made demand that she be allowed to leave. through private companies. their move to cut off material aid from Ms. Bonner's son. Alexei Semyonov, Currently, many parcels are shipped the West, aid that often finds its way to said his mother had begun her own. through private firms that contract persecuted human-rights activists, the hunger strike and was in her fourth day. -

Generate PDF of This Page

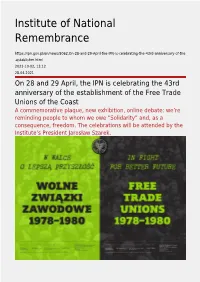

Institute of National Remembrance https://ipn.gov.pl/en/news/8062,On-28-and-29-April-the-IPN-is-celebrating-the-43rd-anniversary-of-the -establishm.html 2021-10-02, 13:12 28.04.2021 On 28 and 29 April, the IPN is celebrating the 43rd anniversary of the establishment of the Free Trade Unions of the Coast A commemorative plaque, new exhibition, online debate: we’re reminding people to whom we owe "Solidarity” and, as a consequence, freedom. The celebrations will be attended by the Institute’s President Jarosław Szarek. The history In 1978, deepening economic depression and growing democratic opposition to the communist rule translated into the establishment of the Free Trade Unions of the Coast. 29 April 1978, the day when the founding charter was officially announced, is widely accepted as the first day of the Unions’ existence. The document was signed by Andrzej Gwiazda, Antoni Sokołowski and Krzysztof Wyszkowski. The charter laid out the organization’s objectives: "The society must fight for and win the right to run the state in a democratic manner . The Unions aim at organizing the protection of economic, legal and human rights of the people.” Consequently, the members safeguarded the basic workers’ rights, commemorated December 1970 massacres, and celebrated the Independence Day. They distributed leaflets and published underground press, always under surveillance of the security services, constantly persecuted, repeatedly arrested, and regularly harassed. Nevertheless, the Unions’ ranks turned out to be the pool from which "Solidarity" drew its best and most determined people. Visit our website devoted to the Free Trade Unions. -

Thoughts on the Meaning of Solidarity

The Missing Commemoration: Thoughts on the Meaning of Solidarity by Eric Chenoweth On the 30th anniversary of the 1989 "velvet revolutions" that resulted in the downfall of communist regimes in the Soviet bloc countries of Central and Eastern Europe, there was little reflection on the most important social and political movement that helped to bring about this transformation of the region. That movement was the Independent and Self-Governing Trade Union, Solidarity in Poland (Solidarność in Polish). Solidarity's importance as a worker and trade union movement in bringing freedom to Eastern Europe has long been overlooked. Indeed, the official conference marking the 25th anniversary of Solidarity's historic rise in 1980 did not even consider its role as a trade union. The following article was written on that occasion in 2005 to explore the fuller meaning of Solidarity. The lost meaning of Solidarity has had profound consequences for the region. Eric Chenoweth was director of the Committee in Support of Solidarity from 1981 to 1988. The August 1980 strikes of Polish workers that led to the signing of the Gdansk Agreements are recognized today as one of the 20th century’s most consequential events. While not altering Poland’s governance, they were revolutionary. By guaranteeing Polish workers the right to freedom of association and the right to strike, the Agreements broke the monopoly control of the communist state over Polish society and shattered the communist party’s claims of legitimacy as the sole representative of a “workers’ state.” Out of the Gdansk Agreements, the free trade union Solidarity emerged with ten million members, nearly the entire industrial and professional workforce. -

Resistance, Gender, Race, and Class in Transgenerational Women's Auto

MISCELLANEA POSTTOTALITARIANA WRATISLAVIENSIA 6/2017 DOI: 10.19195/2353-8546.6.13 ELŻBIETA KLIMEK-DOMINIAK University of Wrocław (Wrocław, Poland)* Daughters and Sons of Solidarity Ask Questions: Resistance, Gender, Race, and Class in Transgenerational Women’s Auto/ biography, Film and New Media1 Daughters and Sons of Solidarity Ask Questions: Resistance, Gender, Race, and Class in Transgenerational Women’s Auto/biography, Film and New Media. Unlike American historians challenging marginalization of women since the 1970s and theorizing usefulness of gender for history, the majority of Polish historians have been rather reluctant to address gender differences. The collapse of communism and transatlantic interest in retraditionalization stimulated interdisciplinary engendering of Solidarity. This article examines how significant, despite being strategically invisible, Solidarity women activists of the 1980s have been represented in oral history, auto/ biography, film and new media as well as in dialogical genres such as auto/biography and relational memoir. The questioning of mythical visions of Solidarity focused on men and class has initially been resisted, but encouraged a debate about gender stereotypes in Poland. The early “archive fever” followed by a recent surge in transgenerational life writing on women oppositionists exploring gender along with ethnicity, class and age has helped to construct multi-layered portraits of anti-communist resistance. In the award-winning documentary and extended interviews, several Solidarity women activists evaluate critically their occa- sional complicity with (post)totalitarian system, which may complicate ultranationalist narratives and fill a number of gaps in postcolonial and post-totalitarian studies of Central and Eastern Europe. Keywords: gender, Solidarity, race, film, new media * Address: Institute of English Studies IFA, ul. -

POLISH INDEPENDENT PUBLISHING, 1976-1989 a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate Scho

MIGHTIER THAN THE SWORD: POLISH INDEPENDENT PUBLISHING, 1976-1989 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. By Siobhan K. Doucette, M.A. Washington, DC April 11, 2013 Copyright 2013 by Siobhan K. Doucette All Rights Reserved ii MIGHTIER THAN THE SWORD: POLISH INDEPENDENT PUBLISHING, 1976-1989 Siobhan K. Doucette, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Andrzej S. Kamiński, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation analyzes the rapid growth of Polish independent publishing between 1976 and 1989, examining the ways in which publications were produced as well as their content. Widespread, long-lasting independent publishing efforts were first produced by individuals connected to the democratic opposition; particularly those associated with KOR and ROPCiO. Independent publishing expanded dramatically during the Solidarity-era when most publications were linked to Solidarity, Rural Solidarity or NZS. By the mid-1980s, independent publishing obtained new levels of pluralism and diversity as publications were produced through a bevy of independent social milieus across every segment of society. Between 1976 and 1989, thousands of independent titles were produced in Poland. Rather than employing samizdat printing techniques, independent publishers relied on printing machines which allowed for independent publication print-runs in the thousands and even tens of thousands, placing Polish independent publishing on an incomparably greater scale than in any other country in the Communist bloc. By breaking through social atomization and linking up individuals and milieus across class, geographic and political divides, independent publications became the backbone of the opposition; distribution networks provided the organizational structure for the Polish underground. -

A Socialist-Feminist Publication Produced by Workers Liberty

OMEN'S W ACK IGHTB 8th March 2019 F A socialist-feminist publication produced by Workers Liberty INSIDE Women Fighting Stalinism Edith Lanchester and 'free love' Social Reproduction Theory Transphobia and materialism Women and the 'alt-right' The socialist roots of International Women's Day One of our placards at the anti-Bolsonaro protest in London last October. Photo: Gemma Short 50p @workersliberty www.fb.com/workersliberty www.workersliberty.org Women Fighting Stalinism Jill Mountford How does a woman who adamantly refused to call And they did so despite carrying the double burden of herself a feminist and was vehemently ‘anti- hard wage-slavery for very poor pay and conditions communist’, who was a passionate Roman Catholic while being valorised as mothers and homemakers. and held Pope John Paul II as one her heroes, and later When women were not working they were queuing, in friend, herself become an inspirational hero for long, long queues for basic food items often at highly socialist feminists? inflated prices. Indeed these highly inflated prices were the catalyst to a wave of strikes and oppressive For starters, she does so by being astonishingly reaction in Lodz in 1971. These class battles courageous; by challenging the crushing Stalinist, anti- galvanised many workers including Anna working class bureaucracy in her workplace over two Walentynowizc and she others worked in underground long decades; by organising an underground workers workers groups until the founding of Solidarnosc is group, and, in doing so, becoming the subject of August 1980. constant harassment and risking imprisonment. Gender inequality in Poland was and is influenced and Anna Walentynowicz with Lech Walesa Anna Walentynowicz was the crane operator in the bolstered by the Catholic Church; by traditional Lenin Shipyard, in Gdansk whose sacking on August 7, nationalist values about women, motherhood and 1980 famously sparked a strike for her reinstatement Matka Polka; and by Stalinism and the glori cation of one week later on August 14. -

TRANSFORMATIONS Comparative Study of Social Transfomtions

TRANSFORMATIONS comparative study of social transfomtions CSST WORKING PAPERS The University of Michigan Ann Arbor CONSTRAINTS ON PROFESSIONAL POWER IN SOVIET-TYPE SOCIETY: INSIGHTS FROM THE SOLIDARITY PERIOD IN POLAND Michael D. Kennedy and Konrad Sadkowski CSST Working CRSO Working Paper #13 Papert371 November 1988 CONSTRAINTS ON PROFESSIONAL POWER IN SOVIET-TYPE SOCIETY: INSIGHTS FROM THE SOLIDARITY PERIOD IN POLAND* Michael D. Kennedy Konrad Sadkowski Department of Sociology Department of History The University of Michigan Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1382 December 17, 1987 *Michael Kennedy wishes to acknowledge the support of fellowships from the International Research and Exchanges Board and the Joint Committee on Eastern Europe of the American Council of Learned Societies and Social Science Research Council, both of which facilitated the collection and interpretation of some of the data in this paper. A grant from the Center for Russian and East 'European Studies of the University of Michigan and a Rackham Faculty Research Grant from the University of Michigan also provided research support for this paper. We also wish to thank Andrzej Krajewski and T. Anthony Jones for their helpful comments on this paper. Please direct correspondence to Michael Kennedy. Forthcoming in T. Anthony Jones (ed.), Profess ions in Social ist Societies. Temple University Press. CONSTRAINTS ON PROFESSIONAL POWER IN SOVIET-TYPE SOCIETY: INSIGHTS FROM THE SOLIDARITY PERIOD IN POL AND^ One of the nightmares facing marxism is that socialist revolution might put a force other than a universal proletariat into power. One Polish participant in the Russian Revolution, Waclaw Machajski, thought that the Bolshevik-inspired transformation of society led to the rule of the East European intellectual stratum, the intelligentsia, rather than of the working class. -

POLAM Fall2020final

THE POLISH AMERICAN CULTURAL INSTITUTE OF MINNESOTA POLFALL 2020 VOLUME 42 ISSUE 3 WWW.PACIM.ORGAM Message from the PACIM President Mary Welke talks about her roots The Pope—My High School friend 1980—The Rise of Solidarity Life in the headlines—Stanisława Walasiewicz Poland off the Beaten Path—Drohiczyn FALL 2020 POLAM 1 From the Editor: POLAM A publication of the Polish Dear POLAM Readers, American Cultural Institute of This year, we celebrate the 40th Anniversary of “Solidarność” in Poland. Thus, the Solidarity Minnesota (PACIM) Published movement became the main focus of this issue. Many of us can recall the days of August 1980 when four times per year. Non-profit the whole world was looking at Poland. Certainly, the current COVID-19 pandemic overshadowed this bulk permit paid at Twin Cities jubilee. “Solidarność” and the creation of the first free trade union in the Soviet Bloc triggered a chain Minnesota. reaction that swept through Central and Eastern Europe and contributed to the Soviet Empire's dissolution. PolAm (Minneapolis, Minn.) The year 2020 brought us many unexpected changes and challenges. Nothing will be as it was before. ISSN 2693-681 (print) It is very much true to me. I experienced the loss of a close family member. At present, I need to slow down and focus on my family. With regret, I must inform you that I decided to step down from the Editor-in-Chief: Katarzyna Litak position of the Editor-in-chief of POLAM. Consequently, this is my last issue. Associate Editor: Donna Sisler Many thanks are necessary. -

NSZZ “Solidarity's”

Studies in Political and Historical Geography Vol. 8 (2019): 207–226 http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/2300-0562.08.11 Krystyna Krawiec-Złotkowska NSZZ “Solidarity’s” notions for the state’s role in social life Their social and political roots and status in 3rd Republic of Poland Abstract: The paper portrays the origins and ideological foundations of NSZZ “Solidarity” (Independent Self-governing Trade Union “Solidarity”) and their meaning in social life at the time of the communist regime in PRL (Polish People’s Republic). There are references to strikes (June ‘56 in Poznan, polish March ’68, June ’76, July ’80 in Lublin and Swidnica and August ’80) and, in 1980, the creation of Inter-Enterprise Strike Committee, which developed and published 21 demands aimed at the authorities. In the study, it is acknowledged that those demands are the ideological sources of Solidarity. The author of the text thinks that John Paul II sermons and encyclicals as well as Fr. Józef Tischner’s texts (published in the book Etyka solidarności oraz Homo sovieticus – Solidarity’s ethics and homo soviecticus) also had an influence on the formation of these ideas, which could bring back moral order, the rule of law, dignity and freedom for the society enslaved by Soviets. “Solidarity” also desired to improve the economic status of the country, particularly by ending the crisis. Those thoughts were, and are, beautiful; unfortunately, nowadays many of them exist only in the sphere of ideas or demands written in NSZZ Solidarity’s statute. Therefore, the article contains a sad conclusion, that in the 3rd Republic of Poland’s reality, “Solidarity’s” ideas are not attractive anymore. -

Instructions

INSTRUCTIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS rules of strike / 5 introduction / 6 scenario / 7 game components / 8 game preparation / 10 sequence of play / 13 player turns / 15 gaining cards from the board / 16 special actions / 20 drawing cards / 22 discarding cards out of the game / 23 end of turn / 24 negotiating demands and the end of the game / 25 advice of the Committee of Experts / 27 how did it happen? / 31 Strike dr Grzegorz Majchrzak / 31 The 21 Demands / 53 Protocol of the Agreement of August 31, 1980 / 57 Members of the Committee of Experts / 61 Members of the MKS Presidium / 62 Biographies / 63 RULES OF STRIKE NUMBER OF PLAYERS: 2–5 AGES: 12+ GAME DURATION: 30–60 minutes GAME DESIGN: Karol Madaj STRIKE! 5 Before August, I was known as a simple worker, one of many union members No one can make a plan for something like a strike. A strike is like a crowd (...) Now I jump to the front, I act independently, I take the leader’s role, which reacts unpredictably, in its own way. I impose my role on the group... INTRODUCTION SCENARIO In the game “Strike”, you get the chance to step into the shoes of Lech Everybody in turn controls the actions of Lech Wałęsa, gaining sup- Wałęsa (pronounced “va-WEN-sa”) and direct the activities of the Inter- port for the strike in the shipyard. You use walking and running cards Enterprise Strike Committee (MKS) in the Vladimir Lenin Shipyard in to move Wałęsa around the board. You use speech cards to win over Gdańsk in August 1980.