180-191 AENSI Journals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aportes Al Conocimiento De La Biota Liquénica Del Oasis De Neblina De Alto Patache, Desierto De Atacama1

Revista de Geografía Norte Grande, 68: 49-64 (2017) Artículos Aportes al conocimiento de la biota liquénica del oasis de neblina de Alto Patache, Desierto de Atacama1 Reinaldo Vargas Castillo2, Daniel Stanton3 y Peter R. Nelson4 RESUMEN Los denominados oasis de neblina son áreas en las zonas costeras del Desierto de Ataca- ma donde el ingreso habitual de niebla permite el establecimiento y desarrollo de diver- sas poblaciones de plantas vasculares, generando verdaderos hotspots de diversidad. En estas áreas, la biota liquenológica ha sido poco explorada y representa uno de los ele- mentos perennes más importantes que conforman la comunidad. En un estudio previo de la biota del oasis de neblina de Alto Patache se reportaron siete especies. Con el fin de mejorar este conocimiento, se analizó la riqueza de especies presentes en el oasis si- guiendo dos transectos altitudinales en diferentes orientaciones del farellón. Aquí repor- tamos preliminarmente 77 especies de líquenes para el oasis de neblina de Alto Patache. De estas, 61 especies corresponden a nuevos registros para la región de Tarapacá, en tanto que las especies Amandinea eff lorescens, Diploicia canescens, Myriospora smarag- dula y Rhizocarpon simillimum corresponden a nuevos registros para el país. Asimismo, se destaca a Alto Patache como la única localidad conocida para Santessonia cervicornis, una especie endémica y en Peligro Crítico. Palabras clave: Oasis de neblina, Desierto de Atacama, líquenes. ABSTRACT Fog oases are zones along the Atacama Desert where the regular input of fog favors the development of rich communities of vascular plants, becoming biodiversity hotspots. In these areas, the lichen biota has been poorly explored and represents one of the most conspicuous elements among the perennials organisms that form the community. -

Integration of Multi Criteria Analysis Methods to a Spatio Temporal Decision Support System for Epidemiological Monitoring

Integration of Multi Criteria Analysis ICAASE'2014 Methods to a Spatio Temporal Decision Support System for Epidemiological Monitoring Integration of Multi Criteria Analysis Methods to a Spatio Temporal Decision Support System for Epidemiological Monitoring Farah Amina Zemri Djamila Hamdadou LIO Laboratory LIO Laboratory BP 1524 EL M’ Naouer, Oran University, Algeria BP 1524 EL M’ Naouer, Oran University, Algeria [email protected] [email protected] Abstract – The present study aims to integrate Multi Criteria Analysis Methods (MCAM) to a decision support system based on SOLAP technology, modeled and implemented in other work. The current research evaluates on the one part the benefits of SOLAP in detection and location of epidemics outbreaks and discovers on another part the advantages of multi criteria analysis methods in the assessment of health risk threatening the populations in the presence of the risk (presence of infectious cases) and the vulnerability of the population (density, socio-economic level, Habitat Type, climate...) all that, in one coherent and transparent integrated decision-making platform. We seek to provide further explanation of the real factors responsible for the spread of epidemics and its emergence or reemergence. In the end, our study will lead to the automatic generation of a risk map which gives a classification of epidemics outbreaks to facilitate intervention in order of priority. Keywords – Multi criteria Analysis Decision Support (MCAM), Spatial Data Mining (SDM), Spatial on Line Analysis Processing (SOLAP), Data warehouse (DW), Epidemiological Surveillance (SE). devoted to the PROMETHEE method tool used for the development of multi criteria decision 1. INTRODUCTION support system suggested. A real case study which is a first validation step of our proposed Epidemic prevention is a public health concern. -

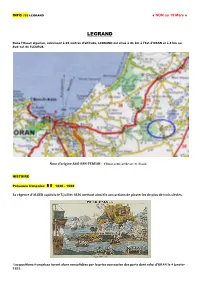

LEGRAND « NON Au 19 Mars »

INFO 753 LEGRAND « NON au 19 Mars » LEGRAND Dans l’Ouest algérien, culminant à 96 mètres d’altitude, LEGRAND est situé à 21 km à l’Est d’ORAN et à 4 km au Sud-est de FLEURUS. Nom d’origine ASSI-BEN-FEREAH - Climat semi-aride sec et chaud. HISTOIRE Présence française 1830 - 1962 La régence d’ALGER capitula le 5 juillet 1830 mettant ainsi fin aux actions de pirateries de plus de trois siècles. Les positions françaises furent alors consolidées par la prise successive des ports dont celui d’ORAN le 4 janvier 1831. Charles DAMREMONT (1793/1837 Constantine) Amable PELISSIER (1794/1864) Louis Juchault LAMORCIERE (1806/1865) C'est dans une ville en grande partie détruite, à la suite du violent tremblement de terre (1790) qu'a connu la ville, peuplée de 2 750 âmes, qu'entrent les Français à ORAN, commandés par le comte Denys de Damrémont. Les événements militaires qui s'étaient succédé sans interruption depuis 1831, n'avaient pas permis de s'occuper sérieusement de colonisation. Ce ne fut guère qu'à la fin de l'année 1845 que, grâce à l'activité et à l'énergie déployées par le général BUGEAUD, aidé des généraux LAMORICIERE et CAVAIGNAC, et du colonel PELISSIER, la province d'Oran se trouva à peu près pacifiée. ABD-EL-KADER ben Muhieddine (1808/1883) Thomas BUGEAUD (1784/1849) Cependant, dès 1841, le général BUGEAUD avait pris l'initiative de la colonisation, et des fermes militaires avaient été créées à MISSERGHIN par les spahis, au camp du Figuier par le 1er bataillon d'infanterie légère, à LA-SENIA par le 56e de ligne. -

BLS Bulletin 111 Winter 2012.Pdf

1 BRITISH LICHEN SOCIETY OFFICERS AND CONTACTS 2012 PRESIDENT B.P. Hilton, Beauregard, 5 Alscott Gardens, Alverdiscott, Barnstaple, Devon EX31 3QJ; e-mail [email protected] VICE-PRESIDENT J. Simkin, 41 North Road, Ponteland, Newcastle upon Tyne NE20 9UN, email [email protected] SECRETARY C. Ellis, Royal Botanic Garden, 20A Inverleith Row, Edinburgh EH3 5LR; email [email protected] TREASURER J.F. Skinner, 28 Parkanaur Avenue, Southend-on-Sea, Essex SS1 3HY, email [email protected] ASSISTANT TREASURER AND MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY H. Döring, Mycology Section, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3AB, email [email protected] REGIONAL TREASURER (Americas) J.W. Hinds, 254 Forest Avenue, Orono, Maine 04473-3202, USA; email [email protected]. CHAIR OF THE DATA COMMITTEE D.J. Hill, Yew Tree Cottage, Yew Tree Lane, Compton Martin, Bristol BS40 6JS, email [email protected] MAPPING RECORDER AND ARCHIVIST M.R.D. Seaward, Department of Archaeological, Geographical & Environmental Sciences, University of Bradford, West Yorkshire BD7 1DP, email [email protected] DATA MANAGER J. Simkin, 41 North Road, Ponteland, Newcastle upon Tyne NE20 9UN, email [email protected] SENIOR EDITOR (LICHENOLOGIST) P.D. Crittenden, School of Life Science, The University, Nottingham NG7 2RD, email [email protected] BULLETIN EDITOR P.F. Cannon, CABI and Royal Botanic Gardens Kew; postal address Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3AB, email [email protected] CHAIR OF CONSERVATION COMMITTEE & CONSERVATION OFFICER B.W. Edwards, DERC, Library Headquarters, Colliton Park, Dorchester, Dorset DT1 1XJ, email [email protected] CHAIR OF THE EDUCATION AND PROMOTION COMMITTEE: S. -

One Hundred New Species of Lichenized Fungi: a Signature of Undiscovered Global Diversity

Phytotaxa 18: 1–127 (2011) ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ Monograph PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2011 Magnolia Press ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) PHYTOTAXA 18 One hundred new species of lichenized fungi: a signature of undiscovered global diversity H. THORSTEN LUMBSCH1*, TEUVO AHTI2, SUSANNE ALTERMANN3, GUILLERMO AMO DE PAZ4, ANDRÉ APTROOT5, ULF ARUP6, ALEJANDRINA BÁRCENAS PEÑA7, PAULINA A. BAWINGAN8, MICHEL N. BENATTI9, LUISA BETANCOURT10, CURTIS R. BJÖRK11, KANSRI BOONPRAGOB12, MAARTEN BRAND13, FRANK BUNGARTZ14, MARCELA E. S. CÁCERES15, MEHTMET CANDAN16, JOSÉ LUIS CHAVES17, PHILIPPE CLERC18, RALPH COMMON19, BRIAN J. COPPINS20, ANA CRESPO4, MANUELA DAL-FORNO21, PRADEEP K. DIVAKAR4, MELIZAR V. DUYA22, JOHN A. ELIX23, ARVE ELVEBAKK24, JOHNATHON D. FANKHAUSER25, EDIT FARKAS26, LIDIA ITATÍ FERRARO27, EBERHARD FISCHER28, DAVID J. GALLOWAY29, ESTER GAYA30, MIREIA GIRALT31, TREVOR GOWARD32, MARTIN GRUBE33, JOSEF HAFELLNER33, JESÚS E. HERNÁNDEZ M.34, MARÍA DE LOS ANGELES HERRERA CAMPOS7, KLAUS KALB35, INGVAR KÄRNEFELT6, GINTARAS KANTVILAS36, DOROTHEE KILLMANN28, PAUL KIRIKA37, KERRY KNUDSEN38, HARALD KOMPOSCH39, SERGEY KONDRATYUK40, JAMES D. LAWREY21, ARMIN MANGOLD41, MARCELO P. MARCELLI9, BRUCE MCCUNE42, MARIA INES MESSUTI43, ANDREA MICHLIG27, RICARDO MIRANDA GONZÁLEZ7, BIBIANA MONCADA10, ALIFERETI NAIKATINI44, MATTHEW P. NELSEN1, 45, DAG O. ØVSTEDAL46, ZDENEK PALICE47, KHWANRUAN PAPONG48, SITTIPORN PARNMEN12, SERGIO PÉREZ-ORTEGA4, CHRISTIAN PRINTZEN49, VÍCTOR J. RICO4, EIMY RIVAS PLATA1, 50, JAVIER ROBAYO51, DANIA ROSABAL52, ULRIKE RUPRECHT53, NORIS SALAZAR ALLEN54, LEOPOLDO SANCHO4, LUCIANA SANTOS DE JESUS15, TAMIRES SANTOS VIEIRA15, MATTHIAS SCHULTZ55, MARK R. D. SEAWARD56, EMMANUËL SÉRUSIAUX57, IMKE SCHMITT58, HARRIE J. M. SIPMAN59, MOHAMMAD SOHRABI 2, 60, ULRIK SØCHTING61, MAJBRIT ZEUTHEN SØGAARD61, LAURENS B. SPARRIUS62, ADRIANO SPIELMANN63, TOBY SPRIBILLE33, JUTARAT SUTJARITTURAKAN64, ACHRA THAMMATHAWORN65, ARNE THELL6, GÖRAN THOR66, HOLGER THÜS67, EINAR TIMDAL68, CAMILLE TRUONG18, ROMAN TÜRK69, LOENGRIN UMAÑA TENORIO17, DALIP K. -

Liste Des Pharmacies Privees

LISTE DES PHARMACIES PRIVEES NOM PRENOM NOM_JFILLE ADR_PROFESSIONNELLE NUM_TEL COMMUNE ABASSI AMINA ABASSI Lotissement El hayette Lot n° 17 Es Sénia ABDELILAH LEILA KHADIDJA ABDELILAH 72 Bd EMIR Khaled Hai Mahieddine Oran ABDELMALEK FEWZIA ZONE USTO Ct DES PYRAMIDE 150 Logts Bloc N°06 RDC Bir El Djir ABDELOUAHAD DJILALI 19 RUE M'KAIDECHE CHERIF KOUIDER Boutlélis ABDRRAHIMI FOUZIA 85 AV EMIR KHALED (041)-34-36-19 Oran ABID HANA EL MEZOUAD cOOP iMMOB 19 jUIN N) 15 lOCAL N) 05 Es Sénia ABIDA SOUMIA ABIDA Hai Bouamama N° 55 Ilot B RDC Oran ABIDELAH MOHAMED lOT N) 33 lOTISSEMENT 73 St Remy Sidi Chami ABLA DAOUD Route de Sidi Benyebka n° 91 Hassi Mefsoukh ACHACHI NABIL Rue Akid Lotfi n° 03 0661-17-60-85 Es Sénia ACHACHI DALILA Hai Akid Abbes Route Nationale 189 B Ain El Turck ADDA DJELLOUL MOHAMED Hai Essabah Ct 338 Logts Bt L 04 n° 02 Sidi Chami ADDI FAIZA ADDI 19 Hai Salem Ilot n° 02 Tafraoui ADNANE AMINE 87 RUE BOUDJEMAA ABDELLAH ECKMUL (041)-36-64-61 Oran AGRED HADJER SAMIHA AGRED Hai El Yasmine Résidence El Nour 18 Bt D1 Local n° 02 et 04 Bir El Djir AINANA NADIA AINANA 83 Chemin de Wilaya Ct 192 Logts Ilot C Bloc 17 n° 67 Es Sénia AINOUCHE MALIK Ct yaghmourassen Hai Ain El Beida Bt B/19 N° 02 Oran AISSANI ZOHRA LAABID 09 ROUTE CANASTEL HAI KHEMISTI Bir El Djir AIT ALLAOUA SALEM Hai Cheikh Bouamama Ilot H5 Lotissement 188 Lots Lot n° 35 Ilot G Oran AIT TAYEB MAHFOUD ISHAK MOUNIR 06 Rue Khiat Bensalem Local n° 02 Hai Chouhadas Oran AKOUN FATIMA ZOHRA TAHRI HAI MAHEDDINE RUE MON SENIEUR KANTAL ANGIF RUE LIEGE N°12 Oran ALABDULRAHMEN SOUMIA -

New Records of Lichens and Lichenicolous Fungi from Fuerteventura (Canary Islands), with Descriptions of Some New Species

Cryptogamie, Mycologie, 2006, 27 (4): 341-374 © 2006 Adac. Tous droits réservés New records of lichens and lichenicolous fungi from Fuerteventura (Canary Islands), with descriptions of some new species P.P.G.van den BOOM1 & J.ETAYO2 1 Arafura 16, NL-5691JA Son, the Netherlands, email: [email protected] 2 Navarro Villoslada 16, 3° dcha, E-31003, Pamplona, Spain, email: [email protected] Abstract – The flora of lichens and lichenicolous fungi of Fuerteventura (Canary Islands) has been studied. The recent catalogue of the Island was composed of 91 species. In the presented annotated list, 98 are additional records of the island, of which 29 species are new to the Canary Islands and among them Caloplaca fuerteventurae , Lecanactiscanariensis , Lichenostigmacanariense and L. episulphurella are described as new. Macaronesia / new taxa / taxonomy / first records / ecology / chemistry / biodiversity Resumen – Se estudia la flora liquénica y de hongos liquenícolas de la isla de Fuerteventura (Islas Canarias). El catálogo de líquenes y hongos liquenícolas de Fuerteventura se componía hasta el momento de 91 de la isla, mientras que en este trabajo se señalan 98 taxones nuevos para la isla, de los que 29 eran desconocidos en las Canarias. Caloplaca fuerteventurae, Lecanactis canariensis, Lichenostigma canariense y L. episulphurella se describen en este trabajo. INTRODUCTION During a one week trip to the Canary Island Fuerteventura in 2001 by the first author and a one week trip by the second author in 2003, lichens and lichenicolous fungi where collected on all available kind of substrata which was encountered. Most of the collected material has been identified and the results are presented below. -

Molecular Phylogeny and Status of Diploicia and Diplotomma, with Observations on Diploicia Subcanescens and Diplotomma Rivas-Martinezii

Lichenologist 34(6): 509-519 (2002) doi:10.1006/lich.2002.0420, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on Molecular phylogeny and status of Diploicia and Diplotomma, with observations on Diploicia subcanescens and Diplotomma rivas-martinezii Maria del Carmen MOLINA, Ana CRESPO, Oscar BLANCO, Nestor HLADUN and David L. HAWKSWORTH Abstract: ITS rDNA sequence data shows that Diploicia and Diplotomma species form a mono- phyletic clade distinct from other Buellia species. This indicates that Diplotomma merits acceptance as a genus, and suggests that Diploicia should be treated as a synonym of Diplotomma, the earlier name. The data also shows Diploicia subcanescens, considered the fertile counterpart in a species pair with D. canescens, is nested within D. canescens and should be treated as a synonym despite reported chemical differences. In addition, the molecular data support the distinctness of Diplotomma rivas-martinezii, a species restricted to gypsum rocks in Spain, from the widespread D. venustum, which grows on calcareous rocks. Aposymbiotic cultures suggest that D. rivas-martinezii also differs from D. venustum in its germination and isolation success rates. One new combination is made: Diplotomma pulverulenta (Anzi) D. Hawksw. (syn. Abrothallus pulverulentus Anzi) for the lichenicolous species previously known as Buellia pulverulenta. V 2002 The British Lichen Society. Published by Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. Key words: Buellia, Lecanorales, lichens, Physciaceae, species pairs, Spain. Introduction Coppins 2002). However, the name has not been universally accepted (e.g. Santesson Since the generic name Diplotomma Flotow 1993; Wirth 1995; Nordin 1996; Vitikainen (Lecanorales, Physciaceae) was resurrected et al. 1997; Diederich & Serusiaux 2000; as distinct from Buellia De Not. -

Studies in Lichen and Lichenicolous Fungi: More Notes on Taxa from North America

MYCOTAXON Volume 108, pp. 491–497 April–June 2009 Studies in lichen and lichenicolous fungi: more notes on taxa from North America James C. Lendemer1*, Jana Kocourková2 & Kerry Knudsen3 *[email protected] 1Cryptogamic Herbarium, Institute of Systematic Botany The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY, 10458–5126, USA 2National Museum, Dept. of Mycology Václavské nám. 68, 115 79 Praha, Czech Republic 3The Herbarium, Dept. of Botany and Plant Sciences University of California, Riverside, CA, 92521–0124, USA Abstract — The following taxa are reported for the first time from North America: Arthonia diploiciae, Opegrapha dolomitica, Reconditella physconiarum, Sarcogyne sphaerospora, and Thalloloma anguiniforme. 1. Arthonia diploiciae Calat. & Diederich, Mycotaxon 55: 366. 1995. Type: Spain, Almeria, Campo de Dalias, Punta del Sabinal, 10 m, on Diploicia canescens on Juniperus phoenicea, 16.iii.1993, E. Barreno et al. s.n. (VAB–lich. 7547, holotype; IMI–362752, isotype). Arthonia diploiciae is a lichenicolous fungus on the thallus of Diploicia canescens (Dicks.) A. Massal., arising in groups of up to 125 ascomata, 70–130 µm each in diameter, and inducing conspicuous brown spots on the thallus of the host. The asci are 4-spored and the ascospores 1-septate, with the lower cell slightly attenuated, apices rounded, 15–22 × 7–12 µm (see illustration and full description in Calatayud et al. 1995). The species was described from Spain and Portugal and has been reported from the Canary Islands and Mexico (Hafellner 1995), Great Britain (Hawksworth 2003) and Ireland (Santesson 1998). Arthonia diploiciae is frequent on D. canescens on the stems of Coreopsis gigantea (Kellogg) H.M. -

Aba Nombre Circonscriptions Électoralcs Et Composition En Communes De Siéges & Pourvoir

25ame ANNEE. — N° 44 Mercredi 29 octobre 1986 Ay\j SI AS gal ABAN bic SeMo, ObVel , - TUNIGIE ABONNEMENT ANNUEL ‘ALGERIE MAROC ETRANGER DIRECTION ET REDACTION: MAURITANIE SECRETARIAT GENERAL Abonnements et publicité : Edition originale .. .. .. .. .. 100 D.A. 150 DA. Edition originale IMPRIMERIE OFFICIELLE et satraduction........ .. 200 D.A. 300 DA. 7 9 et 13 Av. A. Benbarek — ALGER (frais d'expédition | tg}, ; 65-18-15 a 17 — C.C.P. 3200-50 ALGER en sus) Edition originale, le numéro : 2,50 dinars ; Edition originale et sa traduction, le numéro : 5 dinars. — Numéros des années antérleures : suivant baréme. Les tables sont fourntes gratul »ment aux abonnés. Priére dé joindre les derniéres bandes . pour renouveliement et réclamation. Changement d'adresse : ajouter 3 dinars. Tarif des insertions : 20 dinars la ligne JOURNAL OFFICIEL DE LA REPUBLIQUE ALGERIENNE DEMOCRATIQUE ET POPULAIRE CONVENTIONS ET ACCORDS INTERNATIONAUX LOIS, ORDONNANCES ET DECRETS ARRETES, DECISIONS, CIRCULAIRES, AVIS, COMMUNICATIONS ET ANNONCES (TRADUCTION FRANGAISE) SOMMAIRE DECRETS des ceuvres sociales au ministére de fa protection sociale, p. 1230. Décret n° 86-265 du 28 octobre 1986 déterminant les circonscriptions électorales et le nombre de Décret du 30 septembre 1986 mettant fin aux siéges & pourvoir pour l’élection a l’Assemblée fonctions du directeur des constructions au populaire nationale, p. 1217. , ministére de la formation professionnelle et du travail, p. 1230. DECISIONS INDIVIDUELLES Décret du 30 septembre 1986 mettant fin aux fonctions du directeur général da la planification Décret du 30 septembre 1986 mettant fin aux et de. la gestion industrielle au ministére de fonctions du directeur de la sécurité sociale et lindustrie lourde,.p. -

Plan Développement Réseau Transport Gaz Du GR TG 2017 -2027 En Date

Plan de développement du Réseau de Transportdu Gaz 2014-2024 N°901- PDG/2017 N°480- DOSG/2017 CA N°03/2017 - N°021/CA/2017 Mai 2017 Plan de développement du Réseau de Transport du Gaz 2017-2027 Sommaire INTRODUCTION I. SYNTHESE DU PLAN DE DEVELOPPEMENT I.1. Synthèse physique des ouvrages I.2. Synthèse de la valorisation de l’ensemble des ouvrages II. PROGRAMME DE DEVELOPPEMENT DES RESEAUX GAZ II.1. Ouvrages mis en gaz en 201 6 II.2. Ouvrages alimentant la Wilaya de Tamanrasset et Djanet II.3. Ouvrages Infrastructurels liés à l’approvisionnement en gaz nature l II.4. Ouvrages liés au Gazoduc Rocade Est -Ouest (GREO) II.5. Ouvrages liés à la Production d’Electricité II.6. Ouvrages liés aux Raccordement de la C lientèle Industrielle Nouvelle II.7. Ouvrages liés aux Distributions Publiques du gaz II .8. Ouvrages gaz à réhabiliter II. 9. Ouvrages à inspecter II. 10 . Plan Infrastructure II.1 1. Dotation par équipement du Centre National de surveillance II.12 . Prévisions d’acquisition d'équipements pour les besoins d'exploitation II.13 .Travaux de déviation des gazoducs Haute Pression II.1 4. Ouvrages en idée de projet non décidés III. BILAN 2005 – 201 6 ET PERSPECTIVES 201 7 -202 7 III.1. Evolution du transit sur la période 2005 -2026 III.2. Historique et perspectives de développement du ré seau sur la période 2005 – 202 7 ANNEXES Annexe 1 : Ouvrages mis en gaz en 201 6 Annexe 2 : Distributions Publiques gaz en cours de réalisation Annexe 3 : Distributions Publiques gaz non entamées Annexe 4 : Renforcements de la capacité des postes DP gaz Annexe 5 : Point de situation sur le RAR au 30/04/2017 Annexe 6 : Fibre optique sur gazoducs REFERENCE Page 2 Plan de développement du Réseau de Transport du Gaz 2017-2027 INTRODUCTION : Ce document a pour objet de donner le programme de développement du réseau du transport de gaz naturel par canalisations de la Société Algérienne de Gestion du Réseau de Transport du Gaz (GRTG) sur la période 2017-2027. -

Lichens Jennifer Fiorentino Lichen Basics When You

Il-Majjistral Park - Lichens Jennifer Fiorentino Lichen basics When you look at a lichen you are not seeing one organism but at least two. You are seeing a structure (thallus) formed by the interaction of either a fungus with an alga or of a fungus with a cyanobacterium. The fungal partner is called the mycobiont. It is incapable of making food by photosynthesis so it gets its sugar derivatives from the algal (or cyanobacterial) partner called the photobiont. The traditional approach considers lichens as mutualistic associations where both fungal and photobiont partners benefit. Together they are able to deal with ecological conditions that neither part would be able to handle on its own. Let’s face it, would you ever expect to find algae, on their own, growing on the exposed, dry surfaces of rock? Yet protected within the fungal hyphae of their lichen partner they do manage to survive. The fungus absorbs and stores water in its hyphae and provides radiation protection to the algal cell. Similarly the fungal hyphae would not thrive unless they have a source of food and within lichens this is conveniently provided by the photobiont cells. This intimate association does not seem to be harming any of its partners. A closer look at a lichen reveals that the photobiont cells become very leaky when they associate with fungi. The amount of sugars and sugar derivatives that leak out of the walls of photosynthetic algal cells into the fungal hyphae is so large that little food and energy is left for the algae. These are induced to refrain from sexual reproduction and to slow down their rate of growth and vegetative reproduction.