SYMPHONIES of HORROR Musical Experimentation in Howard Shore's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'a-Réalité Virtuelle / Existenz De David Cronenberg

Document généré le 26 sept. 2021 04:42 24 images L’a-réalité virtuelle eXistenZ de David Cronenberg Marcel Jean Stanley Kubrick Numéro 97, été 1999 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/24985ac Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) 24/30 I/S ISSN 0707-9389 (imprimé) 1923-5097 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer ce compte rendu Jean, M. (1999). Compte rendu de [L’a-réalité virtuelle / eXistenZ de David Cronenberg]. 24 images, (97), 50–51. Tous droits réservés © 24 images, 1999 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ e_X_lSten_^__ de David Cronenberg L'A-RÉALITÉ VIRTUELLE PAR MARCEL JEAN n ne s'étonnera guère de constater O que les personnages d'eXistenZ ont, dans le bas du dos, une sorte de prise élec trique (un «bioport») qui leur permet de se brancher directement aux jeux de réalité virtuelle qu'ils utilisent. En effet, les habitués de l'œuvre de Cronenberg savent que chez lui, tout passe par le corps. Il n'y a pas, chez l'auteut de Scanners, de sépararion entre le corps et l'esprit, de sorte qu'un jeu est néces sairement quelque chose de physique. -

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

Self-Negating Images: Towards An-Iconology †

Proceedings Self-Negating Images: Towards An-Iconology † Andrea Pinotti Department of Philosophy “Piero Martinetti”, Università Statale di Milano, 20122 Milano, Italy; [email protected] † Presented at the International and Interdisciplinary Conference IMMAGINI? Image and Imagination between Representation, Communication, Education and Psychology, Brixen, Italy, 27–28 November 2017. Published: 13 December 2017 Abstract: Recent developments in image-making techniques have resulted in a drastic blurring of the threshold between the world of the image and the real world. Immersive and interactive virtual environments have enabled the production of pictures that elicit in the perceiver a strong feeling of being incorporated in a new and autonomous world. In doing so, they negate themselves as “images-of-something”, as icons: they are veritable “an-icons”. This kind of picture undermines the mainstream representationalist paradigm of Western image theories: “presentification” rather than representation is at stake here. My paper will address this challenging iconoscape, arguing for the necessity of a specific methodological approach—namely, an-iconology. Keywords: an-iconology; image theory; media archaeology; presence; representation; immersivity; interactivity; avatar; embodiment; immediacy 1. Introduction The contemporary scenario of image production and consumption is characterized by an ever- increasing blurring of the distinction between image and reality. Immersivity and interactivity in virtual environments are able to elicit -

Sight & Sound Films of 2007

Sight & Sound Films of 2007 Each year we ask a selection of our contributors - reviewers and critics from around the world - for their five films of the year. It's a very loosely policed subjective selection, based on films the writer has seen and enjoyed that year, and we don't deny them the choice of films that haven't yet reached the UK. And we don't give them much time to ponder, either - just about a week. So below you'll find the familiar and the obscure, the new and the old. From this we put together the top ten you see here. What distinguishes this particular list is that it's been drawn up from one of the best years for all-round quality I can remember. 2007 has seen some extraordinary films. So all of the films in the ten are must-sees and so are many more. Enjoy. - Nick James, Editor. 1 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (Cristian Mungiu) 2 Inland Empire (David Lynch) 3 Zodiac (David Fincher) = 4 I’m Not There (Todd Haynes) The Lives of Others (Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck) 6 Silent Light (Carlos Reygadas) = 7 The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (Andrew Dominik) Syndromes and a Century (Apichatpong Weerasethakul) No Country for Old Men (Ethan and Joel Coen) Eastern Promises (David Cronenberg) 1 Table of Contents – alphabetical by critic Gilbert Adair (Critic and author, UK)............................................................................................4 Kaleem Aftab (Critic, The Independent, UK)...............................................................................4 Geoff Andrew (Critic -

HL8028 Monsters in Literature

HL 8028: “Monsters in Literature and Film” “He who fights with monsters should look to it that he himself does not become a monster. And when you gaze long into an abyss the abyss also gazes into you.” —Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil Instructor: Joshua Lam, PhD Email: [email protected] Meeting Time: Wednesdays, 3:30-6:30PM Meeting Place: LT29 (Lecture Theater 29), Block SS2 SS2-B1-16 Course Description This course will introduce you to the literary and cultural study of “monsters” in the modern era, from nineteenth-century gothic literature, through modernism, to the postmodern and contemporary period. The course will introduce you to basic practices of interpretation and analysis, as well as fundamental elements of popular genres in film and literature, including horror, science fiction, and fantasy. Using close reading of literary and visual narratives, our study of these texts will include attention to their historical and cultural backgrounds; to issues of race, gender, sexuality, and disability; and to technology and definitions of the human. The course will include fiction and film, as well as supplementary poetry, music, and visual art. Core Texts to Purchase (2): 1. Octavia Butler, Fledgling. Grand Central, 2007. ISBN: 0446696161 2. Franz Kafka, The Metamorphosis, trans. Susan Bernofsky. Norton, 2014. ISBN: 0393347095 *Note: There are many English translations of The Metamorphosis, but I’d prefer you use the version listed here. It’s much easier to read and funnier than the others. Core Texts to Read: All other required texts will be made available online (NTU Learn). Additional supplementary material (not subject to examination) may be shown or distributed in class. -

D2492609215cd311123628ab69

Acknowledgements Publisher AN Cheongsook, Chairperson of KOFIC 206-46, Cheongnyangni-dong, Dongdaemun-gu. Seoul, Korea (130-010) Editor in Chief Daniel D. H. PARK, Director of International Promotion Department Editors KIM YeonSoo, Hyun-chang JUNG English Translators KIM YeonSoo, Darcy PAQUET Collaborators HUH Kyoung, KANG Byeong-woon, Darcy PAQUET Contributing Writer MOON Seok Cover and Book Design Design KongKam Film image and still photographs are provided by directors, producers, production & sales companies, JIFF (Jeonju International Film Festival), GIFF (Gwangju International Film Festival) and KIFV (The Association of Korean Independent Film & Video). Korean Film Council (KOFIC), December 2005 Korean Cinema 2005 Contents Foreword 04 A Review of Korean Cinema in 2005 06 Korean Film Council 12 Feature Films 20 Fiction 22 Animation 218 Documentary 224 Feature / Middle Length 226 Short 248 Short Films 258 Fiction 260 Animation 320 Films in Production 356 Appendix 386 Statistics 388 Index of 2005 Films 402 Addresses 412 Foreword The year 2005 saw the continued solid and sound prosperity of Korean films, both in terms of the domestic and international arenas, as well as industrial and artistic aspects. As of November, the market share for Korean films in the domestic market stood at 55 percent, which indicates that the yearly market share of Korean films will be over 50 percent for the third year in a row. In the international arena as well, Korean films were invited to major international film festivals including Cannes, Berlin, Venice, Locarno, and San Sebastian and received a warm reception from critics and audiences. It is often said that the current prosperity of Korean cinema is due to the strong commitment and policies introduced by the KIM Dae-joong government in 1999 to promote Korean films. -

A Dangerous Method

A David Cronenberg Film A DANGEROUS METHOD Starring Keira Knightley Viggo Mortensen Michael Fassbender Sarah Gadon and Vincent Cassel Directed by David Cronenberg Screenplay by Christopher Hampton Based on the stage play “The Talking Cure” by Christopher Hampton Based on the book “A Most Dangerous Method” by John Kerr Official Selection 2011 Venice Film Festival 2011 Toronto International Film Festival, Gala Presentation 2011 New York Film Festival, Gala Presentation www.adangerousmethodfilm.com 99min | Rated R | Release Date (NY & LA): 11/23/11 East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Donna Daniels PR Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Donna Daniels Ziggy Kozlowski Carmelo Pirrone 77 Park Ave, #12A Jennifer Malone Lindsay Macik New York, NY 10016 Rebecca Fisher 550 Madison Ave 347-254-7054, ext 101 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 New York, NY 10022 Los Angeles, CA 90036 212-833-8833 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8844 fax 323-634-7030 fax A DANGEROUS METHOD Directed by David Cronenberg Produced by Jeremy Thomas Co-Produced by Marco Mehlitz Martin Katz Screenplay by Christopher Hampton Based on the stage play “The Talking Cure” by Christopher Hampton Based on the book “A Most Dangerous Method” by John Kerr Executive Producers Thomas Sterchi Matthias Zimmermann Karl Spoerri Stephan Mallmann Peter Watson Associate Producer Richard Mansell Tiana Alexandra-Silliphant Director of Photography Peter Suschitzky, ASC Edited by Ronald Sanders, CCE, ACE Production Designer James McAteer Costume Designer Denise Cronenberg Music Composed and Adapted by Howard Shore Supervising Sound Editors Wayne Griffin Michael O’Farrell Casting by Deirdre Bowen 2 CAST Sabina Spielrein Keira Knightley Sigmund Freud Viggo Mortensen Carl Jung Michael Fassbender Otto Gross Vincent Cassel Emma Jung Sarah Gadon Professor Eugen Bleuler André M. -

Remembering Music

lawrence m. zbikowski Remembering Music This article considers the role of memory in musical understanding through an exploration of some of the cognitive resources recruited for musical memory, with a special emphasis on processes of categorization and on the different memory systems which are brought to bear on musical phenomena. This perspective is then developed through a close analysis of the ways memory is exploited and expanded in To- ru Takemitsu’s Equinox, a short work for guitar written in 1993. Early in the second volume of Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu (translated as In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower) the narrator – having overcome a bit of awkwardness with Charles Swann – has become an intimate of Swann’s household, and the favored friend of his daughter Gilberte. On some days he joins the Swanns as they while away the afternoon at home, but on most occasions he joins them for a drive in the Bois de Boulogne. On occasion, before she changes her dress in preparation for their drive, Madame Swann sits down at the piano: The fingers of her lovely hands, emerging from the sleeves of her tea gown in crêpe de Chine, pink, white, or at times in brighter colors, wandered on the keyboard with a wistful- ness of which her eyes were so full, and her heart so empty. It was on one of those days that she happened to play the part of the Vinteuil sonata with the little phrase that Swann had once loved so much.1 This event provides Proust with an opportunity to reflect on the challenges of listening to music, and in particular on the difficulty of making something of a new piece on our first encounter with it. -

24. Debussy Pour Le Piano: Sarabande (For Unit 3: Developing Musical Understanding)

24. Debussy Pour le piano: Sarabande (For Unit 3: Developing Musical Understanding) Introduction and Performance circumstances Debussy probably decided to compose a Sarabande partly because he knew Erik Satie’s three sarabandes of 1887, with their similarly sensuous harmony. There are no grounds for referring to Debussy’s Sarabande as ‘impressionist’, even though the piece is very similar in date to his Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune. The term ‘neoclassical’ may be more suitable, although we do not hear the post-World War I type of ‘wrong-note’ neoclassicism of, for example, Stravinsky’s Pulcinella. In public performance Debussy’s Sarabande is most likely to be heard as part of a piano recital, along with the two other movements which flank it (Prélude and Toccata) from Pour le piano. Incidentally the suite was published in 1901, but the Sarabande (in a slightly different version to the one we know) dates back to 1894. Performing Forces and their Handling Sarabande, for solo piano, does not depend for its effect on any virtuosity or display. Marguerite Long, a pupil of Debussy, noted that the composer ‘himself played [the piece] as no one [else] could ever have done, with those marvellous successions of chords sustained by his intense legato’. A wide range is involved, from (several) very low C sharps to E just over five octaves higher; there are no extremely high notes. Some left-hand chords extend to well over an octave and have to be spread. Texture The texture is almost entirely homophonic, with much parallelism, and is often extremely sonorous on account of the many chords with six or more notes. -

David Cronenberg: Transformaciones Orgánicas Y Psicológicas

David Cronenberg: Transformaciones orgánicas y psicológicas Presentación Este curso está pensado para explorar las obras principales en la filmografía del director canadiense, estudiando su evolución y su consistencia temática a lo largo de toda su carrera vista en orden cronológico. Se discutirán temas como: • La efectividad del cine de género como alegoría y crítica social • El movimiento artístico de la Nueva Carne • El transhumanismo y sus implicaciones filosóficas • Los elementos recurrentes en el cine de Cronenberg • La transición de una etapa “orgánica” a otra más psicológica • La teoría del autor Objetivo: David Cronenberg, nacido en Canadá en 1943, ha sido llamado el “Rey del horror venéreo” y el “Barón de la sangre”. Pero más allá de estas etiquetas llamativas y sensacionalistas, se trata de un director de cine que ha desarrollado una carrera casi siempre desde los géneros marginados del horror y la ciencia ficción, incorporando tanto guiones propios como adaptaciones de literatura y comics, demostrando que es posible tener un acercamiento autoral a dichas vertientes de la ficción. Con temas y elementos recurrentes, su cine ha ido evolucionando al mismo tiempo que retiene sus preocupaciones y su visión del mundo, dando consistencia a una obra a lo largo de cuatro décadas. Este curso pretende explorar su filmografía y, de algún modo, reivindicar el potencial de los mal llamados subgéneros para comunicar temas relevantes. Imparte: Adrián “Pok” Manero Adrián "Pok" Manero (Ciudad de México, 1982). Escritor autodidacta, ha tomado talleres con Alberto Chimal, Eduardo Antonio Parra y Eric Uribares. Ganador del segundo concurso de cuento Caligrama, en cuya antología aparece su primer texto publicado. -

![Petite Diffamation / Maps to the Stars]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2629/petite-diffamation-maps-to-the-stars-412629.webp)

Petite Diffamation / Maps to the Stars]

Document generated on 09/29/2021 4:54 a.m. Séquences La revue de cinéma Petite diffamation Maps to the Stars Julie Demers Number 294, January–February 2015 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/73400ac See table of contents Publisher(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (print) 1923-5100 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Demers, J. (2015). Review of [Petite diffamation / Maps to the Stars]. Séquences, (294), 26–26. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 2015 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ 26 LES FILMS | CRITIQUES DAVID CRONENBERG Maps to Petite the Stars diffamation Julianne Moore est presque nue. La caméra s’approche d’elle, près, trop près. Elle scrute ses rides, les taches sur sa peau. Non, ce n’est pas son beau profil. Non, elle ne capte pas bien la lumière. Parle-t-elle ? Non, elle renifle, grogne, baragouine d’une voix éraillée. Elle est vieille, flétrie. Vulgaire dans sa robe trop transparente et banale au lit. Quelconque en toutes circonstances. Julianne Moore a troqué son élégance contre le Prix d’interprétation à Cannes. JULIE DEMERS ollywood est malade. Et depuis longtemps. -

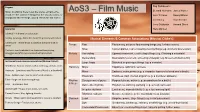

Knowledge Organiser

Key Composers Purpose Bernard Hermann James Horner Music in a film is there to set the scene, enhance the AoS3 – Film Music mood, tell the audience things that the visuals cannot, or John Williams Danny Elfman manipulate their feelings. Sound effects are not music! John Barry Alan Silvestri Jerry Goldsmith Howard Shore Key terms Hans Zimmer Leitmotif – A theme for a character Mickey-mousing – When the music fits precisely with action Musical Elements & Common Associations (Musical Cliche’s) Underscore – where music is played at the same time as action Tempo Fast Excitement, action or fast-moving things (eg. A chase scene) Slow Contemplation, rest or slowing-moving things (eg. A funeral procession) Fanfare – short melodies from brass sections playing arpeggios and often accompanied with percussion Melody Ascending Upward movement, or a feeling of hope (eg. Climbing a mountain) Descending Downward movement, or feeling of despair (eg. Movement down a hill) Instruments and common associations (Musical Clichés) Large leaps Distorted or grotesque things (eg. a monster) Woodwind - Natural sounds such as bird song, animals, rivers Harmony Major Happiness, optimism, success Bassoons – Sometimes used for comic effect (i.e. a drunkard) Minor Sadness, seriousness (e.g. a character learns of a loved one’s death) Brass - Soldiers, war, royalty, ceremonial occasions Dissonant Scariness, pain, mental anguish (e.g. a murderer appears) Tuba – Large and slow moving things Rhythm Strong sense of pulse Purposefulness, action (e.g. preparations for a battle) & Metre Harp – Tenderness, love Dance-like rhythms Playfulness, dancing, partying (e.g. a medieval feast) Glockenspiel – Magic, music boxes, fairy tales Irregular rhythms Excitement, unpredictability (e.g.