Calling and Ordination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Korean-American Methodists' Response to the UMC Debate Over

religions Article Loving My New Neighbor: The Korean-American Methodists’ Response to the UMC Debate over LGBTQ Individuals in Everyday Life Jeyoul Choi Department of Religion, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA; [email protected] Abstract: The recent nationwide debate of American Protestant churches over the ordination and consecration of LGBTQ clergymen and laypeople has been largely divisive and destructive. While a few studies have paid attention to individual efforts of congregations to negotiate the heated conflicts as their contribution to the denominational debate, no studies have recounted how post-1965 immigrants, often deemed as “ethnic enclaves apart from larger American society”, respond to this religious issue. Drawing on an ethnographic study of a first-generation Korean Methodist church in the Tampa Bay area, Florida, this article attempts to fill this gap in the literature. In brief, I argue that the Tampa Korean-American Methodists’ continual exposure to the Methodist Church’s larger denominational homosexuality debate and their personal relationships with gay and lesbian friends in everyday life together work to facilitate their gradual tolerance toward sexual minorities as a sign of their accommodation of individualistic and democratic values of American society. Keywords: homosexuality and LGBTQ people; United Methodist Church; post-1965 immigrants; Korean-American evangelicals Citation: Choi, Jeyoul. 2021. Loving My New Neighbor: The Korean-American Methodists’ Response to the UMC Debate over 1. Introduction LGBTQ Individuals in Everyday Life. The discourses of homosexuality and LGBTQ individuals in American Protestantism Religions 12: 561. https://doi.org/ are polarized by the research that enunciates each denomination’s theological stance 10.3390/rel12080561 and conflicts over the case studies of individual sexual minorities’ struggle within their congregations. -

When You Consider Ordination

WHEN YOU CONSIDER ORDINATION CONSERVATIVE CONGREGATIONAL CHRISTIAN CONFERENCE April 2017 CONTENTS Ff When Considering Ordination • What is the call to Christian Ministry? • Who Should be Ordained? • The Local Church’s Responsibility The Candidate for Ordination • Preparation of Ordination Paper • Recommended Resources for Theological Development The Examination by the Vicinage Council • Some Suggested Forms WHEN CONSIDERING ORDINATION TO CHRISTIAN MINISTRY Ff It is a great and awesome privilege to be ordained or to help someone prepare for ordination. This pamphlet has been designed with candidates for ordination and ordaining churches in mind to help them understand what is involved in the ordina- tion process. To candidates, God’s Word says, “If anyone sets his heart on being an overseer, he desires a noble task” (I Tim.3:1). Our prayer is that God would raise up and call many into His service who are scripturally qualified, Spirit-filled, and zealous for His name. To churches, God’s Word says, “Everything should be done in a fitting and orderly way” (I Cor. 14:40). When we follow this Biblical admonition, we are a model to the candidate, and we reflect the importance we place on ordination. According to By-law VI, Section 2 of our Constitution and By-laws, “A candidate for Ordination to the Christian Ministry and subsequent ministerial membership in this Conference will be expected to have a life which is bearing the fruit of the Spirit, and which is marked by deep spirituality and the best of ethical practices. The candidate may be disqualified by any habits or WHEN YOU CONSIDER ORDINATION practices in his life which do not glorify God in his body, which belongs to God, or which might cause any brother in Christ to stumble.” By-law IV, Section 2, states: “A ministerial standing in this Conference shall require: (1) A minimum academic attainment of a diploma from an accredited Bible institute or the equivalent in formal education or Christian service. -

ORDINATION 2021.Pdf

WELCOME TO THE CATHEDRAL OF SAINT PAUL Restrooms are located near the Chapel of Saint Joseph, and on the Lower Level, which is acces- sible via the stairs and elevator at either end of the Narthex. The Mother Church for the 800,000 Roman Catholics of the Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis, the Cathedral of Saint Paul is an active parish family of nearly 1,000 households and was designated as a National Shrine in 2009. For more information about the Cathedral, visit the website at www.cathedralsaintpaul.org ARCHDIOCESE OF SAINT PAUL AND MINNEAPOLIS SAINT PAUL, MINNESOTA Cover photo by Greg Povolny: Chapel of Saint Joseph, Cathedral of Saint Paul 2 Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis Ordination to the Priesthood of Our Lord Jesus Christ E Joseph Timothy Barron, PES James Andrew Bernard William Duane Duffert Brian Kenneth Fischer David Leo Hottinger, PES Michael Fredrik Reinhardt Josh Jacob Salonek S May 29, 2021 ten o’clock We invite your prayerful silence in preparation for Mass. ORGAN PRELUDE Dr. Christopher Ganza, organ Vêpres du commun des fêtes de la Sainte Vierge, op. 18 Marcel Dupré Ave Maris Stella I. Sumens illud Ave Gabrielis ore op. 18, No. 6 II. Monstra te esse matrem: sumat per te preces op. 18, No. 7 III. Vitam praesta puram, iter para tutum: op. 18, No. 8 IV. Amen op. 18, No. 9 3 HOLY MASS Most Rev. Bernard A. Hebda, Celebrant THE INTRODUCTORY RITES INTROITS Sung as needed ALL PLEASE STAND Priests of God, Bless the Lord Peter Latona Winner, Rite of Ordination Propers Composition Competition, sponsored by the Conference of Roman Catholic Cathedral Musicians (2016) ANTIPHON Cantor, then Assembly; thereafter, Assembly Verses Daniel 3:57-74, 87 1. -

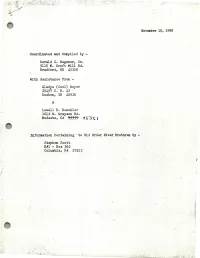

Migration Patterns, Old German Baptist Brethren

November 10, 1988 Coordinated and Compiled by - Gerald C. Wagoner, Sr. 5110 N. Croft Mill Rd. Bradford, OH 45308 With Assistance From - Gladys (Cool) Royer 25457 C. R. 43 Goshen, IN 46526 & Lowell H. Beachier 1612 W. Grayson Rd. Modesto, CA 9'5359 qs3;i information Pertaining to Old Order River Brethren by - Stephen Scott R#1 - Box 362 Columbia, PA 17512 OLD GERMAN BAPTIST BRTHR: MIGRATION PATTERNS October 17, 1988 In the early years, settlement of the Brethren in the eastern portions of the United States, is very ably told by the various Brethren historians. Included in this sto are ancestors of the Old German Baptist Brethren along with family progenitors of all Brethren groups. While this portion of writing deals directly with genealogical interests and pursuits of Old Order families - we will begin by offering a bit of general information. As Brethren began coming to Germantown, Pennsylvania in 1719 & 179, ever pushing westward to new frontiers, the migration never really stopped until they reached the west coast many decades later. Maryland & Virginia began to be settled before the Revolution and just prior to 1800, members were found as far west as Kentucky, Ohio and even Missouri. Through the Pittsburgh and Ohio River gateways, most of the remaining states were settled. Railroads also played a significant role in colonizing the western states. Our attention will now center around migration patterns and family names of brethren in the Old German Baptist Brotherhood. After Kansas, Iowa and Nebraska were settled, cheap land and new frontiers continued to lure the Lrethren westward as the twentieth century approached. -

Myron S. Principies 01 Biblical Interpretation in Mennonite Theology

Augsburger, Myron S. PrincipIes 01 Biblical Interpretation in Mennonite Theology. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1967. Bauman, Clarence. The Spiritual Legacy 01 Hans Denck: Interpretation and Translation 01Key Texts. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1991. Beachy, Alvin J. The Concept 01 Grace in the Radical Relormation. Nieuw- koop: DeGraaf, 1977. Beahm, William M. Studies in Christian Belief Elgin, IlI.: Brethren Press, 1958. Bender, Harold S. Two Centuries 01 American Mennonite Literature, 1727-1928. Goshen, Ind.: Mennonite Historical Society, 1929. Bender, Harold S., ed. Hutterite Studies: Essays by Robert Friedmann. Goshen, Ind.: Mennonite Historical Society, 1961. Bender, Harold S., et al. The Mennonite Encyclopedia. 5 vols. 1955, 1959, 1990. Bittinger, Emmert F. Heritage and Promise: Perspectives on the Church olthe Brethren. Elgin, IlI.: Brethren Press, 1970. Bittinger, Emmert F., ed. Brethren in Transition: 20th Century Directions & Dilemmas. Camden, Maine: Penobseot Press, 1992. Bowman, Carl F. A Profile 01the Church 01the Brethren. Elgin, IL: Brethren Press, 1987. Bowman, Carl F. "Beyond Plainness: Cultural Transformation in the Chureh of the Brethren from 1850 to the Present." Ph.D. Dissertation: University of Virginia, 1989. Bowman, Carl F. Brethren Society: The Cultural Translormation ola "Peculiar People". Baltirnore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995. Bowman, Rufus D. The Church olthe Brethren and War: 1708-1941. Elgin, IlI.: Brethren Publishing House, 1944. Brethren Encyclopedia. The Brethren Encyclopedia. Three Vols. Philadelphia and Oak Brook, IlI.: The Brethren Eneyclopedia, Ine., 1983. Brethren Publishing. The Brethren 's Tracts and Pamphlets, Setting Forth the Claims 01Primitive Christianity. Vol. I. Gish Fund Edition. Elgin, IlI.: Brethren Publishing House. Brethren Publishing. Full Report 01 Proceedings 01 the Brethren 's Annual Meeting. -

The Abrahamic Faiths

8: Historical Background: the Abrahamic Faiths Author: Susan Douglass Overview: This lesson provides background on three Abrahamic faiths, or the world religions called Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. It is a brief primer on their geographic and spiritual origins, the basic beliefs, scriptures, and practices of each faith. It describes the calendars and major celebrations in each tradition. Aspects of the moral and ethical beliefs and the family and social values of the faiths are discussed. Comparison and contrast among the three Abrahamic faiths help to explain what enabled their adherents to share in cultural, economic, and social life, and what aspects of the faiths might result in disharmony among their adherents. Levels: Middle grades 6-8, high school and general audiences Objectives: Students will: Define “Abrahamic faith” and identify which world religions belong to this group. Briefly describe the basic elements of the origins, beliefs, leaders, scriptures and practices of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Compare and contrast the basic elements of the three faiths. Explain some sources of harmony and friction among the adherents of the Abrahamic faiths based on their beliefs. Time: One class period, or outside class assignment of 1 hour, and ca. 30 minutes class discussion. Materials: Student Reading “The Abrahamic Faiths”; graphic comparison/contrast handout, overhead projector film & marker, or whiteboard. Procedure: 1. Copy and distribute the student reading, as an in-class or homework assignment. Ask the students to take notes on each of the three faith groups described in the reading, including information about their origins, beliefs, leaders, practices and social aspects. They may create a graphic organizer by folding a lined sheet of paper lengthwise into thirds and using these notes to complete the assessment activity. -

Brethren Pastors Attend First Latino Leaders Meeting of Christian Churches Together

~~-® .~~~ HILLCREST A REMARKABLE RETIREMENT COMMUNITY® PEACEFULLY. SIMPLY. TOGETHER. HILLCREST. Residential I Assisted I Memory Care I Skilled 2705 Mountain View Drive I La Verne, California I 909-392-4375 www.LivingatHillcrest.org DSS #191501662 I COA #069 CHURCH OF THE BRETHREN ESSENGER Editor: Randy Miller Publisher: Wendy McFadden News: Cheryl Brumbaugh-Cayford Subscriptions: Diane Stroyeck Design: The Concept Mill December 2014 voL.163 No. 10 www.BRETHREN.oRG Beyond the stained glass ceiling 8 The corporate world's "glass ceiling" represents the invisible barrier that keeps women from realizing their full leadership potential. To what extent does the church have its own version of that ceiling? Advent ponderings 12 Although violence and despair appear more prevalent in the world than ever, Advent offers a reason to hope in a season of hope. Anticipating things unseen 13 "Travel teaches," says former Mission and Ministry Board chair Ben Barlow. Sometimes its lessons can be found even in strands of rebar sprouting high atop unfinished buildings, signifying the promise of a brighter future. The shadows lengthen 17 Musings about the good that can be found in both the light and the dark-sparked by a column in these very pages a few months back-sparked the idea for this new hymn from Jay Weaver. Waking up on a silent night 18 Christmas Eve can be so tradition-driven and predictable that we risk missing the message. What will wake us from our sleeping in heavenly peace? departments 2 FROM THE PUBLISHER 20 NEWS 27 LETTERS 3 INTOUCH 24 MEDIA REVIEW 29 TURNING POINTS 6 REFLECTIONS 26 LIVING SIMPLY 30 INDEX 7 THE BUZZ 32 EDITORIAL - FromthePublisher used to be amused at how easily my father could get How to reach us I distracted by an old newspaper. -

Priesthood Ordination

Priesthood Ordination The most humbling task of a bishop, and at the same time a great joy and privilege, is to ordain a priest for service to the Church. It is humbling because it is a moment when the power of Jesus uses a weak human instrument to continue what Jesus did on the night before the died, insuring that his great sacrifice, offered once for all on the Cross on Good Friday, would continue to be with his people. So many of you here have helped bring these deacons to the altar of ordination today. To parents and other family members, to priests, teachers, seminary professors and schoolmates, to friends and associates, I express the thanks of the Archdiocese for your special role. Later, I shall speak in greater detail. Also, I want to call attention to a step that makes today’s Ordination Mass more like other Masses: there will be a collection, and the ordination class has determined that the collection will be divided into three parts, one-third for the education of future priests, one-third for our inner city schools, and one-third for the needs of the Cathedral Church we are privileged to use today. Those to be ordained today have chosen the readings from the word of God that give a color, a flavor, a sense of what is to happen here in the Cathedral of Mary Our Queen. The Church as well, through the extraordinary ministry of Pope John Paul H, to whom the deacons referred in their presentation to me, has made a contribution. -

Magisterial Reformers and Ordination P

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Faculty Publications Church History 1-2013 Magisterial Reformers and Ordination P. Gerard Damsteegt Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/church-history-pubs Part of the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Damsteegt, P. Gerard, "Magisterial Reformers and Ordination" (2013). Faculty Publications. Paper 55. http://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/church-history-pubs/55 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the Church History at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MAGISTERIAL REFORMERS AND ORDINATION By P. Gerard Damsteegt Seventh-day Adventists Theological Seminary, Andrews University 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I. LUTHER AND ORDINATION ............................ Error! Bookmark not defined. Luther’s ordination views as a Roman Catholic priest ..................................... 3 Luther's break from sacramental view of ordination ........................................ 4 Equality of all believers and the function of priests and bishops ..................... 5 Biblical Ordination for Luther .......................................................................... 6 Implementing the biblical model of ordination ......................................... 8 Qualifications for ordination -

2018 3 9 Catalog

LANCASTER MENNONITE HISTORICAL SOCIETY’S BENEFIT AUCTION OF RARE, OUT-OF-PRINT, AND USED BOOKS FRIDAY, MARCH 9, 2018, AT 6:30 P.M. TEL: (717) 393-9745; FAX: (717) 393-8751; EMAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: http://www.lmhs.org/ The Lancaster Mennonite Historical Society will conduct an auction on March 9, 2018, at 2215 Millstream Road, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, one-half mile east of the intersection of Routes 30 and 462. The sale dates for the remainder of 2018 are as follows: May 11, July 13, September 14 and November 9. Please refer to the last page of the catalog for book auction procedures. Individual catalogs are available from the Society for $5.00 + $3.00 postage and handling. Persons who wish to be added to the mailing list for the rest of 2018 may do so by sending $15.00 with name and address to the Society. Higher rates apply for subscribers outside of the United States. All subscriptions expire at the end of the calendar year. The catalog is also available for free on our web site at www.lmhs.org/auction.html. 1. Bender, Harold S. Conrad Grebel, c. 1498-1526, the Founder of the Swiss Brethren, Sometimes Called Anabaptists. Studies in Anabaptist and Mennonite History, no. 6, vol. 1. Goshen, Ind.: Mennonite Historical Society, 1950. xvi, 326pp (b/w ill, bib, ind, copy of author, syp, gc). 2. Friedmann, Robert. Mennonite Piety Through the Centuries: Its Genius and Its Literature. Studies in Anabaptist and Mennonite History, no. 7. Goshen, Ind.: Mennonite Historical Society, 1949. xv, [i], 287pp (fp, b/w ill, bib, ind, presentation copy signed by author, syp, gc). -

'-" Gran a Rapids=------Remarkable Residents

Grappling with issues in ------------'-" Gran a Rapids=----------- Remarkable Residents { Residenis Jerry & Berkley Davis } Jerry and Berkley Davis are very involved at Hillcrest, participating in several --;:/:J,$,;y-~ / aspects of campus life. Jerry heads up --® Channel 3, the community's in-house television station, while Berkley serves on the management team of the Hill HILLCREST crest gift shop and assists with the production of "Hillcrest Happenings;' the community's resident newsletter. "There is more to do and learn here ...........................................A Remarkable Brethren Community than one can imagine;' says Jerry:' "I think we made agood choice in Hillcrest!" • In following our Brethren roots of Peacefully, Simply, Together • On-site full-time Chaplain, vesper services { Resident Shanti111lBhagat } "Hillcrest, a model community for • Three Brethren churches within 5 miles of Hillcrest retirement: orderly not chaotic, • University of La Verne is walking distance from Hillcrest and unambiguously secure living with offers senior audit programs caring residents, friendly responsive associates and staff, top-rated • The Interfaith Festival, Doctor's Symphony and shuttles to physical facilities for swimming, cultural art activities exercising, dining, nursing and healthcare. You are in experienced hands at Hillcrest, why go anywhere else?" • Community Gardens • Great location, campus and weather ........................................... • Hillcrest offers all levels of care. You will be welcomed with { Chaplain TamHostetler} open arms and enjoy the love and comfort of lifelong friends! "Hillcrest. .. what a great place to live and work! As chaplain, I am privileged to participate in the spiritual life of many of the residents and the community as a whole. Opportunities abound for worship at all levels of care; bible studies, phone devotions, sharing and inspiration to meet a variety of needs and ,expectations. -

Pennsylvania Folklife Vol. 18, No. 2 Robert C

Ursinus College Digital Commons @ Ursinus College Pennsylvania Folklife Magazine Pennsylvania Folklife Society Collection Winter 1969 Pennsylvania Folklife Vol. 18, No. 2 Robert C. Bucher Don Yoder Harry H. Hiller Henry Glassie Donald F. Durnbaugh Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/pafolklifemag Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, American Material Culture Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Cultural History Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Folklore Commons, Genealogy Commons, German Language and Literature Commons, Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons, History of Religion Commons, Linguistics Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits oy u. Recommended Citation Bucher, Robert C.; Yoder, Don; Hiller, Harry H.; Glassie, Henry; and Durnbaugh, Donald F., "Pennsylvania Folklife Vol. 18, No. 2" (1969). Pennsylvania Folklife Magazine. 35. https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/pafolklifemag/35 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Pennsylvania Folklife Society Collection at Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pennsylvania Folklife Magazine by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Contributors to This Issue ROBERT C. BUCHER, Schwe nksville, R.D., Pennsyl vania, whose long-time interest in Pennsylvani a's colonial architecture and its restoration involves him in both Gosch enhoppen Historians and HistOric chaefferstOwn, has con tributed several major articles to Pemzs')'lvania Folklife, on such varied subj ects as Grain in the Attic, Red Tile Roof ing, Irrigated Meadows, and the Continental Central-Chim ney Log H ouse.