The Principles of Future-Proofing: a Broader Understanding of Resiliency in the Historic Built Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

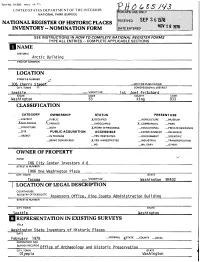

National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC Arctic Building AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 306 Cherry Si _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN & CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Seattle __ VICINITY OF 1 st Joel Pri tchard STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Washington 53 King 033 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC XOCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X-BUILDING(S) ^-PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED ^-COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH X-WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS _YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED XYES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: CHG Citv Center Investors # 6 STREET & NUMBER 1906 One Washington Plaza CITY, TOWN STATE ____Tacoma VICINITY OF Washington 98402 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEED^ETC. Assessors Qff| ce , King County Admi ni s trati on Buil di nq STREET & NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE Seattle Washington REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Washington State Inventory of Historic Places DATE February 1978 —FEDERAL ^STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Qff1ce Of Archaeology and Historic Preservation CITY. TOWN STATE Olympia Washington DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGINALSITE —RUINS X_ALTERED —MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Arctic Building,occupying a site at the corner of Third Avenue and Cherry Street in Seattle, rises eight stories above a ground level of retail shops to an ornate terra cotta roof cornice. -

Data Sheet National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 ^ex. \Q-1 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DATA SHEET NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS | NAME HISTORIC Holyoke Building AND/OR COMMON (same) LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 1018 - 1022 First Avenue or 107 Spring Street _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Seattle VICINITY OF 3rd - Donald L. Bonker STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Washington King CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM ^.BUILDING(S) X_PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL _PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH X_WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL _PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT _RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X_YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Harbor Properties STREET & NUMBER 1411 - 4th Avenue CITY. TOWN STATE Seattle _ VICINITY OF Washington HLOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. King County Courthouse STREETS. NUMBER 3rd Avenue and James Street CITY, TOWN STATE Seattle Washington 98104 H REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Office of Urban Seattle Landmarks Preservation Board - 1st Avenue Study - Conservation, Seattle DATE February 3, 1974 —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Citv nf Seatt1p _ Department of Community Development CITY. TOWN STATE Seattle Washington DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGINALSITE GOOD —RUINS X-ALTERED —MOVED DATE. _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Holyoke Building is a substantial five-story brick masonry commercial block in the Victorian Commercial style. Built in 1890, it was the first office building to be completed after Seattle's disasterous fire of 1889. -

National Register of Historic Places

NPS Form 1900a 0MB No. 1024-00 (Rev. B-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet - Seattle Apar t ment Buildings, 1900-1957 King County, Washingt on Section number Page 49 of 67 designing structural steel skeletons for the large buildings that were beginning to appear. He became a licensed architect in 1923, beginning with several apartment commissions, including the Davenport (1924), the Devonshire (1925), the Windham (1925) and the Stockbridge (1925). However, he primarily designed larger buildings such as the Terminal Sales Building (1923) and the United Shopping Tower (now the Olympic Tower, 1928-31). He is best known for his siunptuous use of terra cotta ornament, as seen in the Eagles Temple (now ACT Theater, 1925), the Music Box Theater (1928, demolished), and the Embassy Theater/Mann Building (1926). Toward the end of his long career he turned to the Streamlined Modeme and International styles, evidenced by the Seattle Post-Intelligencer Building (now Group Health, 1947).^ John Creutzer (d. 1929) first practiced architecture in Minneapolis before moving on to Spokane and then to Seattle in 1906. He worked as a designer and construction supervisor for Alexander Pearson, a contractor and for Henderson Ryan, a prominent architect. His major projects include the Swedish Tabernacle (1906) and the Medical- Dental Building (1927, with A. H. Albertson). His apartment designs include Carolina Court (1915), the Lenawee (1918), the Charbem (1925), Park Vista (1928) and the Julie (now the El Rio, 1929)P Edwin E. Dofsen (1902-1976) began his career as a self-taught draftsman who apprenticed with various Seattle architectural offices. -

By WA:>Nil\L'~~ $,1L"Tt5!' Fl,R.Rm «; PA/?£.E:(\Lstttlcll.~

(Rev. Aug. 2002) (Expires 1-31-2009) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service • • National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 1O-900-a).Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. X New Submission Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Seattle Apartment Buildings, 1900 - 1957 B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Purpose-built Apartment Buildings in Seattle, constructed between 1900 and 1957 C. Form Prepared by name/title Mimi Sheridan AICP street & number 3630 37th Avenue West telephone 206-270-8727 city or town Seattle state ~W.!..!A:L-__ zip code 98199 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. (See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Date WA:>NIl\l'~~ $,1l"tT5!' fl,r.rM «; PA/?£.E:(\lSttTlCll.~ State or Federal Agency or Tribal government I hereby certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. -

APPENDIX H NRHP-Listed Architectural Historic Properties and Districts in the Plan Area

APPENDIX H NRHP-listed Architectural Historic Properties and Districts in the Plan Area June 2014 Draft Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement This appendix lists the architectural historic properties and districts in the Plan area that are National Historic Landmarks or are listed in the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). The list is based on data from the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation (DAHP 2014). The Figure ID numbers in Table H-1 correspond to those ID numbers on Figure H-1 through Figure H-3 while the Figure ID numbers in Table H-2 correspond to those ID numbers on Figure H-4 and Figure H-5. DAHP also maintains records of previously recorded archaeological sites and traditional cultural properties. However, site-specific information about these properties is exempt from public disclosure under state law (RCW 42.56.300) to prevent looting and vandalism. Table H-1. NRHP-listed architectural historic properties in the Plan area Figure ID DAHP ID Property name Historic Designation 1 KI00231 12th Avenue South Bridge NRHP 2 KI00599 1411 Fourth Avenue Building NRHP 3 KI00259 14th Avenue South Bridge NRHP 4 KI01140 1600 East John Street Apartments NRHP 5 KI00773 A. L. Palmer Building NRHP 6 PI00599 Adjutant General's Residence NRHP 7 KI01127 Admiral's House, 13th Naval District NRHP 8 KI00632 Agen Warehouse NRHP 9 KI00243 Alaska Trade Building NRHP 10 PI00696 Albers Brothers Mill NRHP 11 PI00638 Alderton School NRHP 12 PI00705 Annobee Apartments NRHP 13 KI00226 Arboretum Sewer Trestle -

O Print from &

Oprint from & PER is published annually as a single volume. Copyright © 2014 Preservation Education & Research. All rights reserved. Articles, essays, reports and reviews appearing in this journal may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, except for classroom and noncommercial use, including illustrations, in any form (beyond copying permitted by sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law), without written permission. ISSN 1946-5904 Front cover photograph credit: Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc.; back cover credits, top to bottom: Library of Congress, Natalia Sanchez Hernandez; Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc. PRESERVATION EDUCATION & RESEARCH Preservation Education & Research (PER) disseminates international peer-reviewed scholarship relevant to historic environment education from fields such as historic EDITORS preservation, heritage conservation, heritage studies, building Jeremy C. Wells, Roger Williams University and landscape conservation, urban conservation, and cultural ([email protected]) patrimony. The National Council for Preservation Education (NCPE) launched PER in 2007 as part of its mission to Rebecca J. Sheppard, University of Delaware exchange and disseminate information and ideas concerning ([email protected]) historic environment education, current developments and innovations in conservation, and the improvement of historic environment education programs and endeavors in the United BOOK REVIEW EDITOR States and abroad. Gregory Donofrio, University of Minnesota Editorial correspondence, including manuscripts for ([email protected]) submission, should be emailed to Jeremy Wells at jwells@rwu. edu and Rebecca Sheppard at [email protected]. Electronic submissions are encouraged, but physical materials can be ADVISORY EDITORIAL BOARD mailed to Jeremy Wells, SAAHP, Roger Williams University, One Old Ferry Road, Bristol, RI 02809, USA. Articles Steven Hoffman, Southeast Missouri State University should be in the range of 4,500 to 6,000 words and not be Carter L. -

Promoting Seattle During the Gold Rush. a Historic Resource Study for the Seattle Unit of the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 437 334 SO 031 419 AUTHOR Mighetto, Lisa; Montgomery, Marcia Babcock TITLE Hard Drive to the Klondike: Promoting Seattle during the Gold Rush. A Historic Resource Study for the Seattle Unit of the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park. SPONS AGENCY National Park Service (Dept. of Interior), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 1998-11-00 NOTE 407p. AVAILABLE FROM National Park Service, Columbia Cascades Support Office, Attn: Cultural Resources, 909 First Avenue, Seattle, WA 98104-1060. For full text: <http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/k1se/hrstoc.htm>. PUB TYPE Historical Materials (060) Information Analyses (070) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC17 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Built Environment; *Cultural Context; Heritage Education; History Instruction; Local History; *Municipalities; Secondary Education; *Social History; Social Studies; *United States History IDENTIFIERS Alaska; Historical Research; National Register of Historic Places; Urban Development; *Washington (Seattle) ABSTRACT The Alaskan Klondike Gold Rush coincided with major events, including the arrival of the railroad, and it exemplified continuing trends in Seattle's (Washington) history. If not the primary cause of the city's growth and prosperity, the Klondike Gold Rush nonetheless serves as a colorful reflection of the era and its themes, including the celebrated "Seattle spirit." This historic resource study examines the Klondike Gold Rush, beginning in the early 1850's with the founding of Seattle, and ending in 1909 with the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition commemorating the Klondike Gold Rush and the growth of the city. Chapter 1 describes early Seattle and the gold strikes in the Klondike, while the following three chapters analyze (how the city became the gateway to the Yukon, how the stampede to theFar 'North stimulated local businesses, and how the city's infrastructure and boundaries changed during the era of the gold rush. -

Representation in Existing Surveys

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS HISTORIC Northern Life Tower [preferred] AND/OR COMMON _______Seattle Tower____________ LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 1212 - 3rd Avenue —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Seattle ' _ VICINITY OF #7 - Hon. Brock Adams STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Washington 53 King 033 QCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC X.OCCUPIED — AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) X_PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED X-COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _(N PROCESS —YES. RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _ BEING CONSIDERED X.YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Tower Associates STREET & NUMBER Seattle Tower Building, Third and University Street CITY. TOWN STATE Seattle VICINITY OF Washington LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. King County Auditor's Office STREET & NUMBER King Coonty Courthouse CITY. TOWN STATE Seattle Washington REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Seattle Historic Building Survey DATE 1974 —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY X.LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Department Of Community Development CITY. TOWN STATE Arctic Building, 306 Cherry Street, Seattle, Washington DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE 2LEXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ^.ORIGINAL SITE —GOOD _RUINS X-ALTERED _MOVED DATE_______ —FAIR ' _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Northern Life Tower is a 27-story steel frame skyscraper built in 1928 near the center of Seattle's downtown financial district. -

DATA SHEET ^Em UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER of HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM

Form No. 10-300 . \Q-1 DATA SHEET ^eM UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS | NAME HISTORIC Rainier Club AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 810 Fourth Avenue _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Seattle VICINITY OF 1st - Rep. Joel Pritchard STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Washington 53 King 033 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT —PUBLIC X_OCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X-BUILDING(S) ^(.PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY . -X.OTHER: Men ' S Snrial ann tial club, Rainier Club STREET & NUMBER 810 Fourth Avenue CITY. TOWN STATE Seattle VICINITY OF Washington 98104 ! LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. King County Administration Building STREET & NUMBER Fourth Avenue at James Street CITY. TOWN STATE Seattle Washington 98104 | REPRE SENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Washington State Inventory of Historic Places DATE 1972 —FEDERAL JCSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Officc of Archaeology and Historic Preservation CITY. TOWN STATE Olympia Washington 98504 DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGINALSITE X-GOOD __RUINS X_ALTERED MOVED DATE —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE A rare early example of the Jacqbethan Revival Style in Washington, the Rainier Club was designed by Spokane architectsCutier and MaImgren. It was completed and opened for use in _1904. -

I-1 Appendix I HISTORIC RESOURCE SITES

Final Environmental Assessment for Proposed Arrival Procedures to Seattle-Tacoma International Airport Appendix I HISTORIC RESOURCE SITES I-1 1 November 2012 Final Environmental Assessment for Proposed Arrival Procedures to Seattle-Tacoma International Airport I-2 1 November 2012 Final Environmental Assessment for Proposed Arrival Procedures to Seattle-Tacoma International Airport I-3 1 November 2012 Final Environmental Assessment for Proposed Arrival Procedures to Seattle-Tacoma International Airport I-4 1 November 2012 Final Environmental Assessment for Proposed Arrival Procedures to Seattle-Tacoma International Airport I-5 1 November 2012 Final Environmental Assessment for Proposed Arrival Procedures to Seattle-Tacoma International Airport I-6 1 November 2012 Final Environmental Assessment for Proposed Arrival Procedures to Seattle-Tacoma International Airport I-7 1 November 2012 Final Environmental Assessment for Proposed Arrival Procedures to Seattle-Tacoma International Airport I-8 1 November 2012 Final Environmental Assessment for Proposed Arrival Procedures to Seattle-Tacoma International Airport I-9 1 November 2012 Final Environmental Assessment for Proposed Arrival Procedures to Seattle-Tacoma International Airport I-10 1 November 2012 Final Environmental Assessment for Proposed Arrival Procedures to Seattle-Tacoma International Airport Historic Resource Sites within Study Area Name Street Address County State City Date Listed Listing US Quarantine Station 101 Discovery Way, Clallam WA Sequim 5/11/1989 National Surgeon’s Residence -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10·900 OMS No. 1024-0018 (Ocl. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Reg;ster of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bl;Jl1etin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10·900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property Historic name PIONEER SQUARE·SKID ROAD NATIONAL HISTORIC DISTRICT Other names/site number 2. Location Roughly bounded by the Viaduct, Railroad Ave. S., King St, 4'" and 5'" street & number not for publication Avenues, James and Columbia Sts and including the 500 block of 1" Ave South city or town ....,:S=.e:::a:.:tt:.:I:.:e=----- _ vicinity State Washington code WA county King code 033 zip code 98104 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this ..!. nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of H~tgric Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60.