The Gestural Image: the Selfie, Photography Theory, and Kinesthetic Sociability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statement by the Association of Hoving Image Archivists (AXIA) To

Statement by the Association of Hoving Image Archivists (AXIA) to the National FTeservation Board, in reference to the Uational Pilm Preservation Act of 1992, submitted by Dr. Jan-Christopher Eorak , h-esident The Association of Moving Image Archivists was founded in November 1991 in New York by representatives of over eighty American and Canadian film and television archives. Previously grouped loosely together in an ad hoc organization, Pilm Archives Advisory Committee/Television Archives Advisory Committee (FAAC/TAAC), it was felt that the field had matured sufficiently to create a national organization to pursue the interests of its constituents. According to the recently drafted by-laws of the Association, AHIA is a non-profit corporation, chartered under the laws of California, to provide a means for cooperation among individuals concerned with the collection, preservation, exhibition and use of moving image materials, whether chemical or electronic. The objectives of the Association are: a.) To provide a regular means of exchanging information, ideas, and assistance in moving image preservation. b.) To take responsible positions on archival matters affecting moving images. c.) To encourage public awareness of and interest in the preservation, and use of film and video as an important educational, historical, and cultural resource. d.) To promote moving image archival activities, especially preservation, through such means as meetings, workshops, publications, and direct assistance. e. To promote professional standards and practices for moving image archival materials. f. To stimulate and facilitate research on archival matters affecting moving images. Given these objectives, the Association applauds the efforts of the National Film Preservation Board, Library of Congress, to hold public hearings on the current state of film prese~ationin 2 the United States, as a necessary step in implementing the National Film Preservation Act of 1992. -

Lab 11: the Compound Microscope

OPTI 202L - Geometrical and Instrumental Optics Lab 9-1 LAB 9: THE COMPOUND MICROSCOPE The microscope is a widely used optical instrument. In its simplest form, it consists of two lenses Fig. 9.1. An objective forms a real inverted image of an object, which is a finite distance in front of the lens. This image in turn becomes the object for the ocular, or eyepiece. The eyepiece forms the final image which is virtual, and magnified. The overall magnification is the product of the individual magnifications of the objective and the eyepiece. Figure 9.1. Images in a compound microscope. To illustrate the concept, use a 38 mm focal length lens (KPX079) as the objective, and a 50 mm focal length lens (KBX052) as the eyepiece. Set them up on the optical rail and adjust them until you see an inverted and magnified image of an illuminated object. Note the intermediate real image by inserting a piece of paper between the lenses. Q1 ● Can you demonstrate the final image by holding a piece of paper behind the eyepiece? Why or why not? The eyepiece functions as a magnifying glass, or simple magnifier. In effect, your eye looks into the eyepiece, and in turn the eyepiece looks into the optical system--be it a compound microscope, a spotting scope, telescope, or binocular. In all cases, the eyepiece doesn't view an actual object, but rather some intermediate image formed by the "front" part of the optical system. With telescopes, this intermediate image may be real or virtual. With the compound microscope, this intermediate image is real, formed by the objective lens. -

Image Compression Using Discrete Cosine Transform Method

Qusay Kanaan Kadhim, International Journal of Computer Science and Mobile Computing, Vol.5 Issue.9, September- 2016, pg. 186-192 Available Online at www.ijcsmc.com International Journal of Computer Science and Mobile Computing A Monthly Journal of Computer Science and Information Technology ISSN 2320–088X IMPACT FACTOR: 5.258 IJCSMC, Vol. 5, Issue. 9, September 2016, pg.186 – 192 Image Compression Using Discrete Cosine Transform Method Qusay Kanaan Kadhim Al-Yarmook University College / Computer Science Department, Iraq [email protected] ABSTRACT: The processing of digital images took a wide importance in the knowledge field in the last decades ago due to the rapid development in the communication techniques and the need to find and develop methods assist in enhancing and exploiting the image information. The field of digital images compression becomes an important field of digital images processing fields due to the need to exploit the available storage space as much as possible and reduce the time required to transmit the image. Baseline JPEG Standard technique is used in compression of images with 8-bit color depth. Basically, this scheme consists of seven operations which are the sampling, the partitioning, the transform, the quantization, the entropy coding and Huffman coding. First, the sampling process is used to reduce the size of the image and the number bits required to represent it. Next, the partitioning process is applied to the image to get (8×8) image block. Then, the discrete cosine transform is used to transform the image block data from spatial domain to frequency domain to make the data easy to process. -

Ground-Based Photographic Monitoring

United States Department of Agriculture Ground-Based Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station Photographic General Technical Report PNW-GTR-503 Monitoring May 2001 Frederick C. Hall Author Frederick C. Hall is senior plant ecologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Region, Natural Resources, P.O. Box 3623, Portland, Oregon 97208-3623. Paper prepared in cooperation with the Pacific Northwest Region. Abstract Hall, Frederick C. 2001 Ground-based photographic monitoring. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-503. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 340 p. Land management professionals (foresters, wildlife biologists, range managers, and land managers such as ranchers and forest land owners) often have need to evaluate their management activities. Photographic monitoring is a fast, simple, and effective way to determine if changes made to an area have been successful. Ground-based photo monitoring means using photographs taken at a specific site to monitor conditions or change. It may be divided into two systems: (1) comparison photos, whereby a photograph is used to compare a known condition with field conditions to estimate some parameter of the field condition; and (2) repeat photo- graphs, whereby several pictures are taken of the same tract of ground over time to detect change. Comparison systems deal with fuel loading, herbage utilization, and public reaction to scenery. Repeat photography is discussed in relation to land- scape, remote, and site-specific systems. Critical attributes of repeat photography are (1) maps to find the sampling location and of the photo monitoring layout; (2) documentation of the monitoring system to include purpose, camera and film, w e a t h e r, season, sampling technique, and equipment; and (3) precise replication of photographs. -

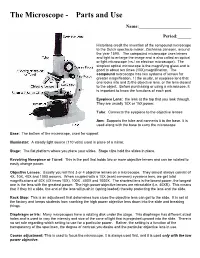

The Microscope Parts And

The Microscope Parts and Use Name:_______________________ Period:______ Historians credit the invention of the compound microscope to the Dutch spectacle maker, Zacharias Janssen, around the year 1590. The compound microscope uses lenses and light to enlarge the image and is also called an optical or light microscope (vs./ an electron microscope). The simplest optical microscope is the magnifying glass and is good to about ten times (10X) magnification. The compound microscope has two systems of lenses for greater magnification, 1) the ocular, or eyepiece lens that one looks into and 2) the objective lens, or the lens closest to the object. Before purchasing or using a microscope, it is important to know the functions of each part. Eyepiece Lens: the lens at the top that you look through. They are usually 10X or 15X power. Tube: Connects the eyepiece to the objective lenses Arm: Supports the tube and connects it to the base. It is used along with the base to carry the microscope Base: The bottom of the microscope, used for support Illuminator: A steady light source (110 volts) used in place of a mirror. Stage: The flat platform where you place your slides. Stage clips hold the slides in place. Revolving Nosepiece or Turret: This is the part that holds two or more objective lenses and can be rotated to easily change power. Objective Lenses: Usually you will find 3 or 4 objective lenses on a microscope. They almost always consist of 4X, 10X, 40X and 100X powers. When coupled with a 10X (most common) eyepiece lens, we get total magnifications of 40X (4X times 10X), 100X , 400X and 1000X. -

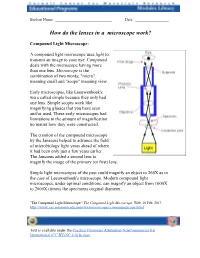

How Do the Lenses in a Microscope Work?

Student Name: _____________________________ Date: _________________ How do the lenses in a microscope work? Compound Light Microscope: A compound light microscope uses light to transmit an image to your eye. Compound deals with the microscope having more than one lens. Microscope is the combination of two words; "micro" meaning small and "scope" meaning view. Early microscopes, like Leeuwenhoek's, were called simple because they only had one lens. Simple scopes work like magnifying glasses that you have seen and/or used. These early microscopes had limitations to the amount of magnification no matter how they were constructed. The creation of the compound microscope by the Janssens helped to advance the field of microbiology light years ahead of where it had been only just a few years earlier. The Janssens added a second lens to magnify the image of the primary (or first) lens. Simple light microscopes of the past could magnify an object to 266X as in the case of Leeuwenhoek's microscope. Modern compound light microscopes, under optimal conditions, can magnify an object from 1000X to 2000X (times) the specimens original diameter. "The Compound Light Microscope." The Compound Light Microscope. Web. 16 Feb. 2017. http://www.cas.miamioh.edu/mbi-ws/microscopes/compoundscope.html Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) license. - 1 – Student Name: _____________________________ Date: _________________ Now we will describe how a microscope works in somewhat more detail. The first lens of a microscope is the one closest to the object being examined and, for this reason, is called the objective. -

The Ontology of the Photographic Image

!"#$%&'()(*+$(,$'"#$-"('(*./0"12$34/*# 56'"(.789:$5&;.#$</=1&$/&;$>6*"$?./+ @(6.2#:$A1)4$B6/.'#.)+C$D()E$FGC$H(E$I$7@644#.C$FJKL9C$00E$IMJ -6N)18"#;$N+:$O&1P#.81'+$(,$Q/)1,(.&1/$-.#88 @'/N)#$ORS:$http://www.jstor.org/stable/1210183 522#88#;:$FTULVUWLLJ$FX:LI Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucal. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Film Quarterly. http://www.jstor.org 4 ANDRE BAZIN The Ontology of the Photographic Image TRANSLATED BY HUGH GRAY Before his untimely death in 1958 Andre Bazin began to review and select for publication his post-World War II writings on the cinema. -

Image Photograph Marc Lafia

Marc Lafia IMAGE PHOTOGRAPH IMAGE PHOTOGRAPH Marc Lafia IMAGE PHOTOGRAPH Foreword by Daniel Coffeen TABLE OF 008 Foreword CONTENTS Daniel Coffeen 016 Image Photograph, an essay 156 Image Photograph, pictures 302 List of pictures 306 Acknowledgments The opening line of Marc Lafia’s book is fantastic: “Photog- a specialized tool we use to record special moments. The FOREWORD raphy as an image.” It’s not a sentence. It doesn’t have the camera is now always on, simultaneously reading, writ- familiar grammar of subject, verb, object. What I love about ing, archiving: the Web, the smart phone, Instagram, sur- Daniel Coffeen it is that it’s not the didactic declaration that “Photography veillance, telemedicine, MRIs, Skype, Chatroulette, ATM is an image.” Something much stranger, and more beauti- cameras, credit card imprints. If before the digital, the ful, is happening here—something more generous. camera kept a distance between photographer and world, in the digital network, technology entwines us—and en- This is how I imagine the scene just before the book twines with us. The relationship between body, self, tech- opens. The photographer peers through his lens onto the nology, and world has shifted. Il n’y a pas de hors-image. world to find Lafia standing there—looking back! Only La- There is no outside the image. fia’s not looking over the head of the camera, bypassing the technology to engage the eyes of the photographer. One way of reading Lafia’s book is that he asks the obvi- No, Lafia is looking through the looking glass itself. -

The Integrity of the Image

world press photo Report THE INTEGRITY OF THE IMAGE Current practices and accepted standards relating to the manipulation of still images in photojournalism and documentary photography A World Press Photo Research Project By Dr David Campbell November 2014 Published by the World Press Photo Academy Contents Executive Summary 2 8 Detecting Manipulation 14 1 Introduction 3 9 Verification 16 2 Methodology 4 10 Conclusion 18 3 Meaning of Manipulation 5 Appendix I: Research Questions 19 4 History of Manipulation 6 Appendix II: Resources: Formal Statements on Photographic Manipulation 19 5 Impact of Digital Revolution 7 About the Author 20 6 Accepted Standards and Current Practices 10 About World Press Photo 20 7 Grey Area of Processing 12 world press photo 1 | The Integrity of the Image – David Campbell/World Press Photo Executive Summary 1 The World Press Photo research project on “The Integrity of the 6 What constitutes a “minor” versus an “excessive” change is necessarily Image” was commissioned in June 2014 in order to assess what current interpretative. Respondents say that judgment is on a case-by-case basis, practice and accepted standards relating to the manipulation of still and suggest that there will never be a clear line demarcating these concepts. images in photojournalism and documentary photography are world- wide. 7 We are now in an era of computational photography, where most cameras capture data rather than images. This means that there is no 2 The research is based on a survey of 45 industry professionals from original image, and that all images require processing to exist. 15 countries, conducted using both semi-structured personal interviews and email correspondence, and supplemented with secondary research of online and library resources. -

Fine Art Reproduction with Digital Photography and Ink-Jet Printing

Fine art reproduction with digital photography and ink-jet printing by Brian P. Lawler Anything that we couldn’t wrap around the drum would This is a revision of a handout that I started eight years be photographed onto 4x5 inch Kodak Ektachrome film, ago. It is a product of practice, research, consulting with and then the resulting film was scanned. numerous experts, and a good deal of failure. I was successful in reproducing Carlen’s painting, I made a deal with my friend Carlen that I would mostly because I was lucky. In subsequent attempts I make a reproduction of one of her paintings. The have not been so lucky. The color has been unacceptable, original hangs in my living room, and she wanted a copy the lighting has been impossible, or a combination of for display in her studio. factors has contributed to various failures. Fine art photography is a complex task, one requiring tremendous attention to detail and the application of care in the selection and placement of lights and camera, selection of lenses, color management and reproduction on appropriate papers. It’s important to the graphic arts and photography fields because there is money to be made in reproducing fine art – whether it’s for sale as art, or as an illustration of art to be printed in a publication or used online. To reproduce artwork successfully, one must build a photographic environment conducive to this work, This is my successful reproduction image of Carlen’s roosters painting. and develop a work flow that allows for correct lighting, I succeeded with this image because it had a reproducible color palette, color management of the source image, and then and I was able to get the lighting to work using cross-polarized filters. -

Computer Graphics & Image Processing

Computer Graphics & Image Processing Computer Laboratory Computer Science Tripos Part IB Neil Dodgson & Peter Robinson Lent 2012 William Gates Building 15 JJ Thomson Avenue Cambridge CB3 0FD http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/ This handout includes copies of the slides that will be used in lectures together with some suggested exercises for supervisions. These notes do not constitute a complete transcript of all the lectures and they are not a substitute for text books. They are intended to give a reasonable synopsis of the subjects discussed, but they give neither complete descriptions nor all the background material. Material is copyright © Neil A Dodgson, 1996-2012, except where otherwise noted. All other copyright material is made available under the University’s licence. All rights reserved. Computer Graphics & Image Processing Lent Term 2012 1 2 What are Computer Graphics & Computer Graphics & Image Processing Image Processing? Sixteen lectures for Part IB CST Neil Dodgson Scene description Introduction Colour and displays Computer Image analysis & graphics computer vision Image processing Digital Peter Robinson image Image Image 2D computer graphics capture display 3D computer graphics Image processing Two exam questions on Paper 4 ©1996–2012 Neil A. Dodgson http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/~nad/ 3 4 Why bother with CG & IP? What are CG & IP used for? All visual computer output depends on CG 2D computer graphics printed output (laser/ink jet/phototypesetter) graphical user interfaces: Mac, Windows, X,… graphic design: posters, cereal packets,… -

A Comparison of Screen/Film and Digital Imaging: Image Processing, Image Quality, and Dose

AAPM 2005-Continuing Education Course in Radiographic and Fluoroscopy Physics and Technology A Comparison of Screen/Film and Digital Imaging: Image Processing, Image Quality, and Dose Ralph Schaetzing, Ph.D. Agfa Corporation Greenville, SC This presentation… O does… O focus on salient characteristics of two projection-radiography acquisition technology classes O Analog: screen/film (S/F) O Digital: generic O does not… O focus on technology details (see other presentations) O Specific technologies used as examples only O address alternatives to projection imaging (i.e., x-sectional) O cheerlead O No technology-class recommendations - too many other issues 1 Digital Image Acquisition Technologies X-ray quanta X-ray quanta Ð intermediÐ ate(s) Direct Indirect Ð meas. output signal meas. output signal Screen/Film Storage Phosphor + + point scan point scan Screen/Film Storage Phosphor + + line scan line scan Commonly called Silicon Strip Pressurized Gas Scintillator Computed + + + Radiography line/slot scan line/slot scan line/slot scan (CR) Photoconductor Scintillator Scintillator + + + flat-panel array area sensor(s) flat-panel array Commonly called Digital Radiography (DR) 2 The Medical Imaging Chain (Analog, Digital) Human ANALOGUE WORLD Acquire (visible) Reproduce Preprocess ProcessProcess (Optimize) Process for Output Store Distribute DIGITAL WORLD 3 (hidden) The Bigger Picture Producers/Competitors Clinical Technical A R e c p Observers q r u S D e o P t r s i r o s d r o e u e c c e Regulators/Standardizers Operational Economic Consumers