Some Observations on SMON from Bombay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antiseptics and Disinfectants for the Treatment Of

Verstraelen et al. BMC Infectious Diseases 2012, 12:148 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/12/148 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Antiseptics and disinfectants for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis: A systematic review Hans Verstraelen1*, Rita Verhelst2, Kristien Roelens1 and Marleen Temmerman1,2 Abstract Background: The study objective was to assess the available data on efficacy and tolerability of antiseptics and disinfectants in treating bacterial vaginosis (BV). Methods: A systematic search was conducted by consulting PubMed (1966-2010), CINAHL (1982-2010), IPA (1970- 2010), and the Cochrane CENTRAL databases. Clinical trials were searched for by the generic names of all antiseptics and disinfectants listed in the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification System under the code D08A. Clinical trials were considered eligible if the efficacy of antiseptics and disinfectants in the treatment of BV was assessed in comparison to placebo or standard antibiotic treatment with metronidazole or clindamycin and if diagnosis of BV relied on standard criteria such as Amsel’s and Nugent’s criteria. Results: A total of 262 articles were found, of which 15 reports on clinical trials were assessed. Of these, four randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were withheld from analysis. Reasons for exclusion were primarily the lack of standard criteria to diagnose BV or to assess cure, and control treatment not involving placebo or standard antibiotic treatment. Risk of bias for the included studies was assessed with the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias. Three studies showed non-inferiority of chlorhexidine and polyhexamethylene biguanide compared to metronidazole or clindamycin. One RCT found that a single vaginal douche with hydrogen peroxide was slightly, though significantly less effective than a single oral dose of metronidazole. -

Identification of Candidate Agents Active Against N. Ceranae Infection in Honey Bees: Establishment of a Medium Throughput Screening Assay Based on N

RESEARCH ARTICLE Identification of Candidate Agents Active against N. ceranae Infection in Honey Bees: Establishment of a Medium Throughput Screening Assay Based on N. ceranae Infected Cultured Cells Sebastian Gisder, Elke Genersch* Institute for Bee Research, Department of Molecular Microbiology and Bee Diseases, Hohen Neuendorf, Germany * [email protected] Abstract OPEN ACCESS Many flowering plants in both natural ecosytems and agriculture are dependent on insect Citation: Gisder S, Genersch E (2015) Identification of Candidate Agents Active against N. ceranae pollination for fruit set and seed production. Managed honey bees (Apis mellifera) and wild Infection in Honey Bees: Establishment of a Medium bees are key pollinators providing this indispensable eco- and agrosystem service. Like all Throughput Screening Assay Based on N. ceranae other organisms, bees are attacked by numerous pathogens and parasites. Nosema apis is Infected Cultured Cells. PLoS ONE 10(2): e0117200. a honey bee pathogenic microsporidium which is widely distributed in honey bee popula- doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0117200 tions without causing much harm. Its congener Nosema ceranae was originally described Academic Editor: Wolfgang Blenau, Goethe as pathogen of the Eastern honey bee (Apis cerana) but jumped host from A. cerana to A. University Frankfurt, GERMANY mellifera about 20 years ago and spilled over from A. mellifera to Bombus spp. quite recent- Received: October 8, 2014 ly. N. ceranae is now considered a deadly emerging parasite of both Western honey bees Accepted: December 20, 2014 and bumblebees. Hence, novel and sustainable treatment strategies against N. ceranae are Published: February 6, 2015 urgently needed to protect honey and wild bees. -

4. Antibacterial/Steroid Combination Therapy in Infected Eczema

Acta Derm Venereol 2008; Suppl 216: 28–34 4. Antibacterial/steroid combination therapy in infected eczema Anthony C. CHU Infection with Staphylococcus aureus is common in all present, the use of anti-staphylococcal agents with top- forms of eczema. Production of superantigens by S. aureus ical corticosteroids has been shown to produce greater increases skin inflammation in eczema; antibacterial clinical improvement than topical corticosteroids alone treatment is thus pivotal. Poor patient compliance is a (6, 7). These findings are in keeping with the demon- major cause of treatment failure; combination prepara- stration that S. aureus can be isolated from more than tions that contain an antibacterial and a topical steroid 90% of atopic eczema skin lesions (8); in one study, it and that work quickly can improve compliance and thus was isolated from 100% of lesional skin and 79% of treatment outcome. Fusidic acid has advantages over normal skin in patients with atopic eczema (9). other available topical antibacterial agents – neomycin, We observed similar rates of infection in a prospective gentamicin, clioquinol, chlortetracycline, and the anti- audit at the Hammersmith Hospital, in which all new fungal agent miconazole. The clinical efficacy, antibac- patients referred with atopic eczema were evaluated. In terial activity and cosmetic acceptability of fusidic acid/ a 2-month period, 30 patients were referred (22 children corticosteroid combinations are similar to or better than and 8 adults). The reason given by the primary health those of comparator combinations. Fusidic acid/steroid physician for referral in 29 was failure to respond to combinations work quickly with observable improvement prescribed treatment, and one patient was referred be- within the first week. -

Clioquinol: Summary Report

Clioquinol: Summary Report Item Type Report Authors Gianturco, Stephanie L.; Pavlech, Laura L.; Storm, Kathena D.; Yoon, SeJeong; Yuen, Melissa V.; Mattingly, Ashlee N. Publication Date 2020-01 Keywords Clioquinol; Compounding; Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, Section 503B; Food and Drug Administration; Outsourcing facility; Drug compounding; Legislation, Drug; United States Food and Drug Administration Rights Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Download date 24/09/2021 22:12:31 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10713/12091 Summary Report Clioquinol Prepared for: Food and Drug Administration Clinical use of bulk drug substances nominated for inclusion on the 503B Bulks List Grant number: 2U01FD005946 Prepared by: University of Maryland Center of Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation (M-CERSI) University of Maryland School of Pharmacy January 2020 This report was supported by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of a financial assistance award (U01FD005946) totaling $2,342,364, with 100 percent funded by the FDA/HHS. The contents are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement by, the FDA/HHS or the U.S. Government. 1 Table of Contents REVIEW OF NOMINATIONS ................................................................................................... 4 METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................... -

Effect of 8-Hydroxyquinoline and Derivatives on Human Neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y Cells Under High Glucose

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Crossref Effect of 8-hydroxyquinoline and derivatives on human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells under high glucose Wilasinee Suwanjang1, Supaluk Prachayasittikul2 and Virapong Prachayasittikul3 1 Center for Research and Innovation, Faculty of Medical Technology, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand 2 Center of Data Mining and Biomedical Informatics, Faculty of Medical Technology, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand 3 Department of Clinical Microbiology and Applied Technology, Faculty of Medical Technology, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand ABSTRACT 8-Hydroxyquinoline and derivatives exhibit multifunctional properties, including antioxidant, antineurodegenerative, anticancer, anti-inflammatory and antidiabetic activities. In biological systems, elevation of intracellular calcium can cause calpain activation, leading to cell death. Here, the effect of 8-hydroxyquinoline and derivatives (5-chloro-7-iodo-8-hydroxyquinoline or clioquinol and 8-hydroxy-5-nitroquinoline or nitroxoline) on calpain-dependent (calpain-calpastatin) pathways in human neu- roblastoma (SH-SY5Y) cells was investigated. 8-Hydroxyquinoline and derivatives ameliorated high glucose toxicity in SH-SY5Y cells. The investigated compounds, particularly clioquinol, attenuated the increased expression of calpain, even under high- glucose conditions. 8-Hydroxyquinoline and derivatives thus adversely affected the promotion of neuronal cell death by high glucose via the calpain-calpastatin -

EAR, NOSE and OROPHARYNX Updated: October 2020

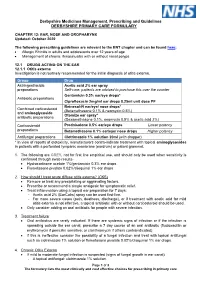

Derbyshire Medicines Management, Prescribing and Guidelines DERBYSHIRE PRIMARY CARE FORMULARY CHAPTER 12: EAR, NOSE AND OROPHARYNX Updated: October 2020 The following prescribing guidelines are relevant to the ENT chapter and can be found here: • Allergic Rhinitis in adults and adolescents over 12 years of age • Management of chronic rhinosinusitis with or without nasal polyps 12.1 DRUGS ACTING ON THE EAR 12.1.1 Otitis externa Investigation is not routinely recommended for the initial diagnosis of otitis externa. Group Drug Astringent/acidic Acetic acid 2% ear spray preparations Self-care: patients are advised to purchase this over the counter Gentamicin 0.3% ear/eye drops* Antibiotic preparations Ciprofloxacin 2mg/ml ear drops 0.25ml unit dose PF Betnesol-N ear/eye/ nose drops* Combined corticosteroid (Betamethasone 0.1% & neomycin 0.5%) and aminoglycoside Otomize ear spray* antibiotic preparations (Dexamethasone 0.1%, neomycin 0.5% & acetic acid 2%) Corticosteroid Prednisolone 0.5% ear/eye drops Lower potency preparations Betamethasone 0.1% ear/eye/ nose drops Higher potency Antifungal preparations Clotrimazole 1% solution 20ml (with dropper) * In view of reports of ototoxicity, manufacturers contra-indicate treatment with topical aminoglycosides in patients with a perforated tympanic membrane (eardrum) or patent grommet. 1. The following are GREY, not for first line empirical use, and should only be used when sensitivity is confirmed through swab results- • Hydrocortisone acetate 1%/gentamicin 0.3% ear drops • Flumetasone pivalate 0.02%/clioquinol 1% ear drops 2. How should I treat acute diffuse otitis externa? (CKS) • Remove or treat any precipitating or aggravating factors. • Prescribe or recommend a simple analgesic for symptomatic relief. -

Chemical Modulators of Fibrinogen Production and Their Impact on Venous Thrombosis

Published online: 2020-12-10 Coagulation and Fibrinolysis 433 Chemical Modulators of Fibrinogen Production and Their Impact on Venous Thrombosis Rui Vilar1 Samuel W. Lukowski1,2 Marco Garieri1 Corinne Di Sanza1 Marguerite Neerman-Arbez1,3 Richard J. Fish1 1 Department of Genetic Medicine and Development, University of Address for correspondence Richard J. Fish, Department of Genetic Geneva Faculty of Medicine, Geneva, Switzerland Medicine and Development, Faculty of Medicine, University of 2 Institute for Molecular Bioscience, The University of Queensland, Geneva, 1, rue Michel-Servet, Geneva 1206, Switzerland Saint Lucia, Queensland, Australia (e-mail: [email protected]). 3 iGE3, Institute of Genetics and Genomics in Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland Thromb Haemost 2021;121:433–448. Abstract Thrombosis is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality. Fibrinogen, the soluble substrate for fibrin-based clotting, has a central role in haemostasis and thrombosis and its plasma concentration correlates with cardiovascular disease event risk and a prothrombotic state in experimental models. We aimed to identify chemical entities capable of changing fibrinogen production and test their impact on experimental thrombosis. A total of 1,280 bioactive compounds were screened for their ability to alter fibrinogen production by hepatocyte-derived cancer cells and a selected panel was tested in zebrafish larvae. Anthralin and all-trans retinoic acid (RA) were identified as fibrinogen-lowering and fibrinogen-increasing moieties, respectively. In zebrafish larvae, anthralin prolonged laser-induced venous occlusion times and reduced thrombocyte accumulation at injury sites. RA had opposite effects. Treatment with RA, a nuclear receptor ligand, increased fibrinogen mRNA levels. Using an antisense morpholino oligonucleotide to deplete zebra- fish fibrinogen, we correlated a shortening of laser-induced venous thrombosis times with RA treatment and fibrinogen protein levels. -

Raised Serum Protein-Bound Iodine After Topical Clioquinol A. C

Case reports 515 Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.47.549.515 on 1 July 1971. Downloaded from Raised serum protein-bound iodine after topical clioquinol A. C. UPJOHN H-J. B. GALBRAITH M.R.C.S., L.R.C.P. M.D., F.R.C.P. General Practitioner, Ongar Physician, Chelmsford Hospitals BETHEL SOLOMONS M.D., F.R.C.P.I. Dermatologist, Chelmsford Hospitals RAISED serum levels ofprotein-bound iodine (PBI) in hydrocortisone cream, and continued to do so for 17 patients with normal thyroid function have been weeks until her first out-patient visit to the skin observed on many occasions after oral treatment department (B. S.). Apart from her varicose condi- with 5-chloro-7-iodo-8-hydroxyquinoline (iodo- tion she. complained of constant nervousness. chlorhydroxyquinoline, clioquinol, Enterovioform) Further examination revealed some signs of thyro- (Thoren, 1960; Levin, Josephson & Grtnewald, toxicosis. The PBI was 22 tug/100 ml. She stopped 1966; Sonksen et al., 1968). It is less well appre- using the cream, and 3 weeks later her PBI was 5-2 Protected by copyright. ciated that clioquinol administered topically can [ug/100 ml. She agreed to use the cream again, and be absorbed in sufficient quantities to influence after 3 weeks, during which time she had used nearly the PBI and the uptake of radio-active iodine by the three 20 g tubes, her PBI was 13-4 [g/100 ml. She thyroid gland. then stopped using the cream and her PBI had returned to 5 0 tzg/100 ml a month later. -

Effectiveness of 7.5 Percent Povidone Iodine in Comparison to 1 Percent Clotrimazole in the Treatment of Otomycosis

EFFECTIVENESS OF 7.5 PERCENT POVIDONE IODINE IN COMPARISON TO 1 PERCENT CLOTRIMAZOLE IN THE TREATMENT OF OTOMYCOSIS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF M.S BRANCH –IV (OTORHINOLARYNGOLOGY EXAMINATION OF THE DR.MGR. MEDICAL UNIVERSITY TO BE HELD IN APRIL 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my deep gratitude to Dr Anand Job, Professor and Head of Unit 1, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Speech and Hearing, Christian Medical College and Hospital, Vellore for his able guidance and encouragement in conducting this study and preparing this dissertation. I wish to express my deep gratitude to Dr Achamma Balraj, Head of the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Speech and Hearing, Christian Medical College and Hospital, Vellore for her able guidance and encouragement in conducting this study and preparing this dissertation. I would like to thank Dr Rita Ruby Albert, Dr Regi Thomas, and Dr Rajan Sundaresan from the Department of Otorhinolaryngology for being my co-investigators in this study. I am extremely thankful to Dr Shalini Anandan, Assistant professor, Department of Microbiology for her guidance in this study. I am thankful to Dr Selvaraj from the Department of Biostatistics for his able guidance in the statistical analysis of this study. I would like to thank the Fluid Research Committee, CMC Hospital for granting me financial assistance for conducting this study. Last but not the least; I would like to thank all my patients who participated with me in this study for their kind co-operation. CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the dissertation entitled “Effectiveness of 7.5 percent povidone iodine in comparison to 1 percent clotrimazole in the treatment of otomycosis” is a bonafide original work of Dr Ajay Philip, submitted in partial fulfillment of the rules and regulations for the MS Branch IV, Otorhinolaryngology examination of The Tamil Nadu Dr. -

Vr Meds Ex01 3B 0825S Coding Manual Supplement Page 1

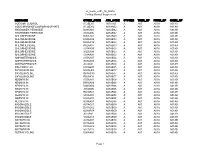

vr_meds_ex01_3b_0825s Coding Manual Supplement MEDNAME OTHER_CODE ATC_CODE SYSTEM THER_GP PHRM_GP CHEM_GP SODIUM FLUORIDE A12CD01 A01AA01 A A01 A01A A01AA SODIUM MONOFLUOROPHOSPHATE A12CD02 A01AA02 A A01 A01A A01AA HYDROGEN PEROXIDE D08AX01 A01AB02 A A01 A01A A01AB HYDROGEN PEROXIDE S02AA06 A01AB02 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE B05CA02 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE D08AC02 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE D09AA12 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE R02AA05 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S01AX09 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S02AA09 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S03AA04 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B A07AA07 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B G01AA03 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B J02AA01 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB POLYNOXYLIN D01AE05 A01AB05 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE D08AH03 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE G01AC30 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE R02AA14 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN A07AA01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN B05CA09 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN D06AX04 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN J01GB05 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN R02AB01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S01AA03 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S02AA07 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S03AA01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE A07AC01 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE D01AC02 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE G01AF04 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE J02AB01 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE S02AA13 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB NATAMYCIN A07AA03 A01AB10 A A01 -

Metronidazole Neuropathy

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.39.4.403 on 1 April 1976. Downloaded from Journal ofNeurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 1976, 39, 403-405 Metronidazole neuropathy A. COXON AND C. A. PALLIS From the Department of Medicine (Neurology), Royal Postgraduate Medical School, London SYN oP si s Two patients are described who developed sensory neuropathy after the ingestion of 30.6 and 114 g metronidazole respectively. The drug, widely used in gastroenterological and gynaecological practice, has not hitherto been considered neurotoxic. The implications are stressed in relation to the differential diagnosis of patients with gastroenterological disorders who develop peripheral neuropathy. In view of the recent advocacy, from Sweden, of ness in the toes. Within a few days this had spread to long-term metronidazole therapy for Crohn's involve the soles and the dorsa of the feet. She could disease (Ursing and Kamme, 1975) and of dis- not feel the ground under her properly, and was not sure whether she was wearing shoes or not. Distres- cussions as to whether the drug might prove Protected by copyright. sing paraesthesiae had developed in the wake of this useful as a 'radio-sensitizing' agent before the numbness. For a few days she had also been aware of administration of radiotherapy (Urtasun et al., ' soreness' in the fingers, which constantly felt cold. 1974), we feel it worth stressing the possible Neurological examination revealed no abnormali- neurotoxic effects of this substance. We here ties in the cranial nerves and no focal weakness or report two personally observed cases of sensory wasting in the limbs. -

Known Bioactive Library: Microsource 1 - US Drug Collection

Known Bioactive Library: Microsource 1 - US Drug Collection ICCB-L ICCB-L Vendor Vendor Compound Name Bioactivity Source CAS Plate Well ID antifungal, inhibits Penicillium 2091 A03 Microsource 00200046 GRISEOFULVIN 126-07-8 mitosis in metaphase griseofulvum 3505-38-2, 486-16-8 2091 A04 Microsource 01500161 CARBINOXAMINE MALEATE antihistaminic synthetic [carbinoxamine] 2091 A05 Microsource 00200331 SALSALATE analgesic synthetic 552-94-3 muscle relaxant 2091 A06 Microsource 01500162 CARISOPRODOL synthetic 78-44-4 (skeletal) antineoplastic, 2091 A07 Microsource 00210369 GALLIC ACID insect galls 149-91-7 astringent, antibacterial 66592-87-8, 50370-12- 2091 A08 Microsource 01500163 CEFADROXIL antibacterial semisynthetic 2 [anhydrous], 119922- 89-9 [hemihydrate] Rheum palmatum, 2091 A09 Microsource 00211468 DANTHRON cathartic 117-10-2 Xyris semifuscata 27164-46-1, 25953-19- 2091 A10 Microsource 01500164 CEFAZOLIN SODIUM antibacterial semisynthetic 9 [cefazolin] glucocorticoid, 2091 A11 Microsource 00300024 HYDROCORTISONE adrenal glands 50-23-7 antiinflammatory 64485-93-4, 63527-52- 2091 A12 Microsource 01500165 CEFOTAXIME SODIUM antibacterial semisynthetic 6 [cefotaxime] 2091 A13 Microsource 00300029 DESOXYCORTICOSTERONE ACETATE mineralocorticoid adrenocortex 56-47-3 58-71-9, 153-61-7 2091 A14 Microsource 01500166 CEPHALOTHIN SODIUM antibacterial semisynthetic [cephalothin] 2091 A15 Microsource 00300034 TESTOSTERONE PROPIONATE androgen, antineoplastic semisynthetic 57-85-2 24356-60-3, 21593-23- 2091 A16 Microsource 01500167 CEPHAPIRIN SODIUM