Mental Models High School Students Hold of Zoos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Today a Treasure Yesterday a Dream

Yesterday a Dream Today a Treasure 2010 REPORT TO THE COMMUNITY We hope you will enjoy this annual report as it takes you on a journey through the last Table of Contents 100 years at the Saint Louis Treasured Memories Zoo. Many changes have been made throughout the Y esterday a Dream, Today a Treasure…Tomorrow a Promise ..........................................................3 years, but the heart of the Memories Abound .......................................................................................................................5 Zoo remains the same: A Zootennial Celebration ..............................................................................................................7 Animals Always. Enriching the Community .............................................................................................................9 JoAnn Arnold Animals Always ..........................................................................................................................11 Chair, Saint Louis Zoological The Living Promise – A Campaign for the Future .........................................................................13 Park Subdistrict Commission Jeffrey P. Bonner, Ph.D. Donors, Volunteers and Staff Dana Brown President & CEO St. Louis Zoological Park Subdistrict Commission .......................................................................18 Saint Louis Zoo Association Board of Directors ...........................................................................18 Endowment Trust Board of Directors ...........................................................................................20 -

Public Perceptions of Behavioral Enrichment: Assumptions Gone Awry

Zoo Biology 17:525–534 (1998) Public Perceptions of Behavioral Enrichment: Assumptions Gone Awry M.E. McPhee,1* J.S. Foster,2 M. Sevenich,3 and C.D. Saunders4 1University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 2Seneca Zoo Society, Rochester, New York 3Disney’s Animal Kingdom, Lake Buena Vista, Florida 4Brookfield Zoo, Brookfield, Illinois More and more, zoos are integrating behavioral enrichment programs into their management routines. Given the newness of such programs on an official level, however, there are an increasing number of enrichment decisions based on as- sumption. Enrichment is typically not provided on exhibit, especially for exhib- its considered to be more naturalistic, because it is assumed to affect visitors’ experience negatively. To test that assumption, visitors were interviewed in front of four exhibits—an outdoor barren grotto, an outdoor vegetated grotto, an in- door immersion exhibit, and an outdoor traditional cage—each with either natu- ral, nonnatural or no enrichment objects present. Specifically, we wanted to know whether 1) the exhibit’s perceived educational message, 2) the animal’s per- ceived “happiness,” and 3) the visitor perceptions of enrichment, the naturalism of animal’s behavior, and zoo animal well-being changed as a function of object type. Overall, the type of enrichment object had little impact on visi- tor perceptions. In the outdoor barren grotto, only visitor perceptions of ex- hibit naturalism were affected by object type. In the outdoor vegetated grotto, object type influenced visitors perceptions of enrichment and exhibit natu- ralism. For the indoor immersion exhibit, general perceptions of enrichment and the perceived naturalism of the animal’s behavior were affected. -

Copyrighted Material

A A COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL Fig. A1 A is for aardvark ( Orycteropus afer ). Dictionary of Zoo Biology and Animal Management: A guide to terminology used in zoo biology, animal welfare, wildlife conservation and livestock production, First Edition. Paul A. Rees. © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Published 2013 by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 1 2 A A See ADENINE (A) Causes loss of appetite, poor growth and, in extreme A aardvark ( Orycteropus afer ) Traditionally the animal cases, death from bleeding. that represents the letter A in the alphabet. It is the abomasum In RUMINANTS , the fourth (and last) only extant member of the mammalian family stomach. It is a ‘ secretory stomach ’ the lining of Orycteropodidae. Adults are the size of a small pig, which produces hydrochloric acid and PROTEO- with little body hair (Fig. A1 ). The aardvark is NOC- LYTIC ENZYMES , and is therefore equivalent to the TURNAL and lives in underground burrows. It pos- stomach of other mammals. sesses large ears, a long snout and a long thin tongue aboral Located on the side of the body opposite which it uses for collecting insects. Its limbs are the mouth, especially in relation to ECHINODERM specialised for digging ( see also FOSSORIAL ). Aard- anatomy. Compare ORAL varks occur in Africa south of the Sahara. abortion, miscarriage The natural or intentional ter- AAZK See A MERICAN A SSOCIATION OF Z OO K EEP- mination of a pregnancy by the removal or expul- ERS (AAZK) . See also KEEPER ASSOCIATION sion of the EMBRYO or FOETUS . Spontaneous AAZPA American Association of Zoological Parks abortion (miscarriage) may result from a problem and Aquariums, now the A SSOCIATION OF that arises during the development of the embryo Z OOS AND A QUARIUMS (AZA) . -

Jim Full Resume 2015.Indd

Education Jim Brighton, Principal 1985 Master of Landscape Architecture, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 1973 Bachelor of Science, Ornamental Horticulture, Cornell University Registration 1990 Landscape Architect, State of Washington 2006 Landscape Architect, State of Texas, State of Ohio 2012 Landscape Architect, States of Utah and Oklahoma Professional Memberships 1993-present American Society of Landscape Architects, ASLA 1998-present American Zoo and Aquarium Association Professional Practice 2003-present Principal: PJA Architects + Landscape Architects, P.S., Seattle, Washington 1999-2003 Principal: Jones & Jones Architects & Landscape Architects, Seattle, Washington 1994-1999 Senior Associate: Jones & Jones Architects & Landscape Architects, Seattle, Washington 1990-1994 Associate: Jones & Jones Architects & Landscape Architects, Seattle, Washington 1985-1990 Senior Associate: Arnold Associates, Princeton, New Jersey Publications Elephant trails at the National Zoo Resumé The American Association of Zoos and Aquariums, National Conference, 2010 Orangutan Sanctuary: Design for Natural Behaviors The American Association of Zoos and Aquariums, National Conference, 2007 A Walk Through Time: Pine Jog Environmental Center Interpretive Trail National Association for Interpretation, Annual Workshop, 2004 Zoo Master Planning & Exhibit Design for the 21st Century The AZA/CACG, Zoo Design Symposium, Shanghai, China P.R., 2004 Collaboration, Cooperation & Commitment: A New Tapir Habitat at Summit Zoo 2nd Annual Tapir Symposium, Panama City, Panama, 2004 Trail of the Elephant: Entertainment, Education, and Enrichment. The American Association of Zoos and Aquariums, National Conference, 2003 Tell Me a Story: Education & Entertainment -- The Reid Park Zoo Master Plan. The American Association of Zoos and Aquariums, Western Regional Conference, 2002 Active Interpretation at the Trail of the Elephant Exhibit. National Association for Interpretation, Annual Workshop, 2001 Planning Eco-Tourism Facilities: Suriname, A Case Study. -

TPG Index Volumes 1-35 1986-2020

Public Garden Index – Volumes 1-35 (1986 – 2020) #Giving Tuesday. HOW DOES YOUR GARDEN About This Issue (continued) GROW ? Swift 31 (3): 25 Dobbs, Madeline (continued) #givingTuesday fundraising 31 (3): 25 Public garden management: Read all #landscapechat about it! 26 (W): 5–6 Corona Tools 27 (W): 8 Rocket science leadership. Interview green industry 27 (W): 8 with Elachi 23 (1): 24–26 social media 27 (W): 8 Unmask your garden heroes: Taking a ValleyCrest Landscape Companies 27 (W): 8 closer look at earned revenue. #landscapechat: Fostering green industry 25 (2): 5–6 communication, one tweet at a time. Donnelly, Gerard T. Trees: Backbone of Kaufman 27 (W): 8 the garden 6 (1): 6 Dosmann, Michael S. Sustaining plant collections: Are we? 23 (3/4): 7–9 AABGA (American Association of Downie, Alex. Information management Botanical Gardens and Arboreta) See 8 (4): 6 American Public Gardens Association Eberbach, Catherine. Educators without AABGA: The first fifty years. Interview by borders 22 (1): 5–6 Sullivan. Ching, Creech, Lighty, Mathias, Eirhart, Linda. Plant collections in historic McClintock, Mulligan, Oppe, Taylor, landscapes 28 (4): 4–5 Voight, Widmoyer, and Wyman 5 (4): 8–12 Elias, Thomas S. Botany and botanical AABGA annual conference in Essential gardens 6 (3): 6 resources for garden directors. Olin Folsom, James P. Communication 19 (1): 7 17 (1): 12 Rediscovering the Ranch 23 (2): 7–9 AAM See American Association of Museums Water management 5 (3): 6 AAM accreditation is for gardens! SPECIAL Galbraith, David A. Another look at REPORT. Taylor, Hart, Williams, and Lowe invasives 17 (4): 7 15 (3): 3–11 Greenstein, Susan T. -

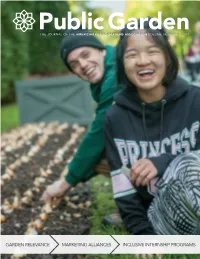

Public Garden

Public Garden THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN PUBLIC GARDENS ASSOCIATION VOLUME 34, ISSUE 1, 2019 GARDEN RELEVANCE MARKETING ALLIANCES INCLUSIVE INTERNSHIP PROGRAMS < Back to Table of Contents Public Garden is looking for your best shot! ROUGH CONSERVATORIES Send a high res, 11”X17” landscape-orientation photo for the Photosynthesis feature to [email protected]. Subject is your choice. CLEARLY SUPERIOR The Rough tradition of excellence continues at Daniel Stowe Botanical Garden. Since 1932 Rough has been building We have the experience, resources, and maintaining large, high-quality and technical expertise to solve your glazed structures, including: design needs. For more information • arboretums about Rough Brothers’ products and • botanical gardens services, call 1-800-543-7351, or visit • conservatories our website: www.roughbros.com DESIGN SERVICES 5513 Vine Street MANUFACTURING Cincinnati OH 45217 SYSTEMS INTEGRATION ph: 800 543.7351 CONSTRUCTION www.roughbros.com THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN PUBLIC GARDENS ASSOCIATION VOLUME 34, ISSUE 1, 2019 FOCAL POINTS 6 THE GARDEN AND THE CITY: EXPANDING RELEVANCE IN RURAL SOUTH CAROLINA This small garden is working to bring horticulture to its community as part of an effort to revitalize the city and expand people’s awareness of the garden and of horticulture. Learn how they are accomplishing this in an unique partnership. 10 ALLIANCES ENHANCE MARKETING EFFORTS Increasingly public gardens should consider alliances to strategically increase exposure, share resources, and provide greater -

AR Vjbmumbai 1920.Pdf

1 CONTENTS S.No Section Page Number Report of the Officer-in-charge 3-4 History of the Zoo 5 Vision 6 Mission 7 Objective 8 About us 9-11 Organizational Chart 12 Human Resources 13-14 Capacity Building of the zoo personnel 15 Zoo Advisory Committee 15 Health Advisory Committee 15 Statement of income and expenditure of the Zoo 16 Daily feed Schedule of animals 17-22 Vaccination Schedule of animals 23 De-worming Schedule of animals 24 Disinfection Schedule 25 Health Check-up of employees for zoonotic diseases 27-28 Development Works carried out in the zoo during the year 29-36 Education and Awareness programmes during the year 37-41 Important Events and happenings in the zoo 42-44 Seasonal special arrangements for upkeep of animals 45-47 Research Work carried out and publications 47 Conservation Breeding Programme of the Zoo 47 Animal acquisition / transfer / exchange during the year 47-49 Rescue and Rehabilitation of the wild animals carried out by the zoo 50 Annual Inventory of animals 51-55 Mortality of animals 56-57 Status of the Compliance with conditions stipulated by the Central Zoo 58-61 Authority List of free living wild animals within the zoo premises 62-63 2 1. Report of the Officer-in-charge MUNCIPAL CORPORATION OF GREATER MUMBAI VEERMATA JIJABAI BHOSALE UDYAN & ZOO From Director's Desk Veermata Jijabai Bhosale Udyan & Zoo, Byculla, Mumbai is now undergoing a revamp and various facilities have been upgraded like public amenities, new garden plots, improvised animal health care facilities, etc. are now operational. Under the phase 2 of modernisation project, new animal exhibits are built on immersion exhibit concept. -

DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For

LABORATORIES, LYCEUMS, LORDS: THE NATIONAL ZOOLOGICAL PARK AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF HUMANISM IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY AMERICA DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Daniel A. Vandersommers, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Professor Randolph Roth, Advisor Professor John L. Brooke Professor Chris Otter Copyright by Daniel A. Vandersommers 2014 ABSTRACT This dissertation tells the story of how a zoo changed the world. Certainly, Charles Darwin shocked scientists with his 1859 publication On the Origin of Species, by showing how all life emerged from a common ancestor through the process of natural selection. Darwin’s classic, though, cannot explain why by the end of the century many people thought critically about the relationship between humans and animals. To understand this phenomenon, historians need to look elsewhere. Between 1870 and 1910, as Darwinism was debated endlessly in intellectual circles, zoological parks appeared suddenly at the heart of every major American city and had (at least) tens of millions of visitors. Darwin’s theory of evolution inspired scientists and philosophers to theorize about humans and animals. Public zoos, though, allowed the multitudes to experience daily the similarities between the human world and the animal kingdom. Upon entering the zoo, Americans saw the world’s exotic species for the first time—their long necks, sharp teeth, bright colors, gargantuan sizes, ivory extremities, spots, scales, and stripes. Yet, more significantly, Americans listened to these animals too. They learned to take animals seriously as they interacted with them along zoo walkways. -

Dana Brown President &

Dana Brown President & CEO POSITION SPECIFICATION THE OPPORTUNITY The Saint Louis Zoo seeks the next Dana Brown President & CEO (President, Chief Executive Officer, CEO) to lead the Zoo at a time of financial and operational strength, as well as great potential. The CEO will provide the vision and strategy to guide an organization already established as a frontrunner in conservation and visitor experience that draws nearly 3 million attendees annually and is the most-visited attraction in the region. As the world’s first municipally supported zoo, Saint Louis Zoo is also one of the few remaining that offers free admission to the public. Guests love their time at the Zoo, with 97% of them rating their experiences as excellent or very good. Acknowledged as one of the top nine best zoos by Travel + Leisure, the Saint Louis Zoo was voted the best zoo in the nation by USA Today in their Readers’ Choice Awards contest in 2018 and by Always Pets in 2021; it is ranked number four in the world by TourScanner; and, in 2017, TripAdvisor put the Zoo among the top six globally. Position Specification: Dana Brown President & CEO 2 The CEO will be a leader with a global footprint, who builds on Saint Louis Zoo’s existing assets, spearheading all aspects of one of the world’s most important zoological parks and conservation organizations. The institution’s next leader will build on the organization’s highly credible position in a role that extends beyond the boundaries of the Zoo’s historic urban campus. The President will set the vision and strategic direction of the Zoo’s conservation efforts, exercising broad oversight of the Zoo’s global field conservation initiatives and participating in the WildCare Institute’s individual centers and programs. -

Land of Lemurs an Opportunity to Invest in Education, Conservation and Economic Development

CPS2015-0935 ATTACHMENT LAND OF LEMURS AN OPPORTUNITY TO INVEST IN EDUCATION, CONSERVATION AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT 1 CPS2015-0848 Attachment.pdf Calgary Zoo 1 ISC: UNRESTRICTED CPS2015-0935 ATTACHMENT The need to share conservation success stories that inspire people, especially young people, to protect the world has never been greater. CPS2015-0848 Attachment.pdf Calgary Zoo 2 ISC: UNRESTRICTED CPS2015-0935 ATTACHMENT INSPIRING CHANGE When children share the same space with black‐and‐white ruffed lemurs, look into their vivid eyes, admire the distinctive white ruffs that frame their faces and listen for their unmistakable chorus of calls, they are doing much more than simply observing these playful, inquisitive animals. They are making connections with nature that will last a lifetime. Creating these kinds of connections is a critical part of the zoo’s plan for the future. We have a responsibility to take the thousands of inspirational moments that happen at the zoo every day and turn them into something greater. But we don’t have the luxury of time. Species in our backyard and around the world are in serious trouble. Something needs to change. Fortunately, there is hope. Today, the Calgary Zoo is ramping up its commitment to conservation by thinking bigger and aiming higher. Land of Lemurs is our first project in an exciting new Master Plan – Inspiring Change – that will see the zoo through its next 20 year Master Plan. New animal habitats and programs, including Land of Lemurs, will focus on animal welfare and conservation; but simply providing opportunities to see endangered species in a world-class exhibit isn’t enough. -

International Zoo News Vol. 50/5 (No

International Zoo News Vol. 50/5 (No. 326) July/August 2003 CONTENTS OBITUARY – Patricia O'Connor EDITORIAL FEATURE ARTICLES Reptiles in Japanese Collections. Part 1: Ken Kawata Chelonians, 1998 Breeding Birds of Paradise at Simon Bruslund Jensen and Sven Hammer Al Wabra Wildlife Preservation An Artist Visits Two Chinese Zoos Frank Pé Variation in Reliability of Measuring Tony King, Elke Boyen and Sander Muilerman Behaviours of Reintroduced Orphan Gorillas Letter to the Editor Book Reviews Conservation Miscellany International Zoo News Recent Articles * * * OBITUARY Patricia O'Connor Dr Patricia O'Connor Halloran made history when she took the position of the staff veterinarian of the Staten Island Zoo, New York, in 1942: she became the first full-time woman zoo veterinarian (and, quite possibly, the first woman zoo veterinarian) in North America. She began her zoo work at a time when opportunities for career-oriented women were limited. Between 1930 and 1939, only 0.8 percent of graduates of American and Canadian veterinary schools were women (the figure had increased to more than 60 percent by the 1990s). At her husband's suggestion she continued to use her maiden name O'Connor as her professional name. For nearly three decades until her retirement in 1970 she wore many hats to keep the zoo going, especially during the war years. She was de facto the curator of education, as well as the curator of mammals and birds. A superb organizer, she helped found several organizations, including the American Association of Zoo Veterinarians (AAZV). Dr O'Connor became the AAZV's first president from 1946 to 1957, and took up the presidency again in 1965. -

DESIGN GUIDELINES for GIZA ZOO by MARWA GEWAILY

VISITOR EXPERIENCE IN ZOO DESIGN: DESIGN GUIDELINES FOR GIZA ZOO by MARWA GEWAILY (Under the direction of David Spooner) ABSTRACT Animal welfare organizations have developed criteria for zoo institutions with animal welfare as a top priority. This research aims to identify design guidelines for the Giza Zoo from the ‘visitor experience’ point of view, where the visitor experience is set as a base line to measure the effectiveness of zoo exhibits. The research identifies authenticity, aesthetics, recreation, education, and exploration as basic components of the visitor experience. These components are defined throughout the research, examined through case studies of the elephant and lion exhibits in three zoos, and are refined to further define visitor experience in the Giza Zoo. A redesign for the elephant and lion exhibits in the zoo is proposed based on these guidelines. INDEX WORDS: Zoological gardens, Giza Zoo, Animal welfare organizations, Zoo history, Visitor experience, Animal exhibits, Design guidelines. VISITOR EXPERIENCE IN ZOO DESIGN DESIGN GUIDELINES FOR GIZA ZOO by MARWA GEWAILY B.S , Ain Shams University, Egypt, 2000 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE ATHENS, GEORGIA 2010 © 2010 Marwa Gewaily All Rights Reserved VISITOR EXPERIENCE IN ZOO DESIGN: DESIGN GUIDELINES FOR GIZA ZOO by MARWA GEWAILY Major Professor: David Spooner Committee: Marianne Cramer Pratt Cassity Josh Koons Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2010 Acknowledgments I would like to thank my major professor David Spooner for his support, guidance and patience, my reading committee for their interest and time: Marianne Cramer, Pratt Cassity, and Josh Koons.