Full Report of Seminar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

House of Commons Official Report Parliamentary

Thursday Volume 664 26 September 2019 No. 343 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Thursday 26 September 2019 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2019 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 843 26 SEPTEMBER 2019 Speaker’s Statement 844 there will be an urgent question later today on the House of Commons matter to which I have just referred, and that will be an opportunity for colleagues to say what they think. This is something of concern across the House. It is Thursday 26 September 2019 not a party political matter and, certainly as far as I am concerned, it should not be in any way, at any time, to any degree a matter for partisan point scoring. It is The House met at half-past Nine o’clock about something bigger than an individual, an individual party or an individual political or ideological viewpoint. Let us treat of it on that basis. In the meantime, may I just ask colleagues—that is all I am doing and all I can PRAYERS do as your representative in the Chair—please to lower the decibel level and to try to treat each other as opponents, not as enemies? [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] Sir Peter Bottomley (Worthing West) (Con): On a point of order, Mr Speaker. Speaker’s Statement Mr Speaker: Order. I genuinely am not convinced, but I will take one point of order if the hon. Gentleman Mr Speaker: Before we get under way with today’s insists. -

View Early Day Motions PDF File 0.12 MB

Published: Thursday 3 December 2020 Early Day Motions tabled on Wednesday 2 December 2020 Early Day Motions (EDMs) are motions for which no days have been fixed. The number of signatories includes all members who have added their names in support of the Early Day Motion (EDM), including the Member in charge of the Motion. EDMs and added names are also published on the EDM database at www.parliament.uk/edm [R] Indicates that a relevant interest has been declared. New EDMs 1225 Scientists, researchers and clinicians developing treatment, testing and vaccines for covid-19 Tabled: 2/12/20 Signatories: 6 Olivia Blake Mick Whitley Bell Ribeiro-Addy Apsana Begum Rachel Hopkins Ian Byrne That this House celebrates and commends the international efforts of thousands of scientists, researchers and clinicians from across the globe in developing treatment, testing and vaccines for covid-19. 1226 Stepps Community Foodbank Tabled: 2/12/20 Signatories: 1 Steven Bonnar That this House congratulates the efforts of Stepps Community Development Trust in establishing a community foodbank for use during the course of the covid-19 pandemic; praises inclusivity and the cooperative approach adopted by ensuring uniform access to service provision; and commends the contributions of the Stepps community and thanks the loyal volunteers for their dedication to the cause. 2 Thursday 3 December 2020 EARLY DAY MOTIONS 1227 Coatbridge businesses and Lanarkshire Business Excellence Awards Tabled: 2/12/20 Signatories: 1 Steven Bonnar That this House congratulates My Roof -

Key Challenges Facing the Ministry of Justice

House of Commons Public Accounts Committee Key challenges facing the Ministry of Justice Fifty-Second Report of Session 2019–21 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 18 March 2021 HC 1190 Published on 24 March 2021 by authority of the House of Commons The Committee of Public Accounts The Committee of Public Accounts is appointed by the House of Commons to examine “the accounts showing the appropriation of the sums granted by Parliament to meet the public expenditure, and of such other accounts laid before Parliament as the committee may think fit” (Standing Order No. 148). Current membership Meg Hillier MP (Labour (Co-op), Hackney South and Shoreditch) (Chair) Mr Gareth Bacon MP (Conservative, Orpington) Kemi Badenoch MP (Conservative, Saffron Walden) Shaun Bailey MP (Conservative, West Bromwich West) Olivia Blake MP (Labour, Sheffield, Hallam) Sir Geoffrey Clifton-Brown MP (Conservative, The Cotswolds) Barry Gardiner MP (Labour, Brent North) Dame Cheryl Gillan MP (Conservative, Chesham and Amersham) Peter Grant MP (Scottish National Party, Glenrothes) Mr Richard Holden MP (Conservative, North West Durham) Sir Bernard Jenkin MP (Conservative, Harwich and North Essex) Craig Mackinlay MP (Conservative, Thanet) Shabana Mahmood MP (Labour, Birmingham, Ladywood) Sarah Olney MP (Liberal Democrat, Richmond Park) Nick Smith MP (Labour, Blaenau Gwent) James Wild MP (Conservative, North West Norfolk) Powers Powers of the Committee of Public Accounts are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No. 148. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2021. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Monday Volume 687 18 January 2021 No. 161 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 18 January 2021 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2021 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 601 18 JANUARY 2021 602 David Linden [V]: Under the Horizon 2020 programme, House of Commons the UK consistently received more money out than it put in. Under the terms of this agreement, the UK is set to receive no more than it contributes. While universities Monday 18 January 2021 in Scotland were relieved to see a commitment to Horizon Europe in the joint agreement, what additional funding The House met at half-past Two o’clock will the Secretary of State make available to ensure that our overall level of research funding is maintained? PRAYERS Gavin Williamson: As the hon. Gentleman will be aware, the Government have been very clear in our [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] commitment to research. The Prime Minister has stated Virtual participation in proceedings commenced time and time again that our investment in research is (Orders, 4 June and 30 December 2020). absolutely there, ensuring that we deliver Britain as a [NB: [V] denotes a Member participating virtually.] global scientific superpower. That is why more money has been going into research, and universities will continue to play an incredibly important role in that, but as he Oral Answers to Questions will be aware, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy manages the research element that goes into the funding of universities. -

The Fife Council - Policy, Finance & Asset Management Committee - Glenrothes

2007.P.F.A.M.1 THE FIFE COUNCIL - POLICY, FINANCE & ASSET MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE - GLENROTHES. 2nd August, 2007 10.00 a.m. - 1.25 p.m. 2.00 p.m. - 2.50 p.m. PRESENT: Councillors Peter Grant (Chair), David Alexander, Andrew Arbuckle, Tim Brett, Pat Callaghan, Douglas Chapman, Neil Crooks, Dave Dempsey, Fiona Grant, Mark Hood, George Kay, William Kay, Alice McGarry, Tony Martin, Bryan Poole, Elizabeth Riches, Joe Rosiejak, David Ross, Alex Rowley, Mike Scott-Hayward, John Simpson and Alice Soper. ATTENDING: Ronnie Hinds, Chief Executive; Michael Enston, Executive Director (Performance & Organisational Support); Iain Grant, Committee Manager and Steve Thompson, Committee Administrator, Law & Administration Service; Lynne Harvie, Organisational Development Manager, Policy & Organisational Development Service; Lesley Ratomska, Communications Officer, Customer Relations Management Service; Ian Robertson, Head of Service Support and Michael McArdle, Lead Professional (Estates), Service Support; Steve Grimmond Head of Community Services; Brian Livingston, Financial Services Manager and Eileen Rowand, Accounting Team Leader, Finance & Procurement Service; and John Alexander, Senior Manager, Social Work Service. APOLOGY FOR ABSENCE: Councillor George Leslie. 1. WELCOME AND INTRODUCTIONS This being the first meeting of the Policy, Finance & Asset Management Committee, Councillor Peter Grant welcomed those present to the meeting and introductions were made. 2. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST Councillor Bryan Poole declared an interest in paragraph 15 as manager of CVS Fife. Councillor David Ross declared an interest in paragraph 15 by reason of his carrying out work for a group mentioned in the report on this item. 3. MEMBERSHIP OF COMMITTEE Members considered a report dated 2nd July, 2007 by the Head of Law and Administration detailing the membership of the Committee. -

Gender and Brexit the Performance of Toxic Masculinity in House of Commons Debates During the Brexit Process

Gender and Brexit the performance of toxic masculinity in House of Commons debates during the Brexit process Evelien Müller | 4688325 Radboud University Bachelor Thesis Prof. dr. Anna van der Vleuten 3 July 2020 Müller, 4688325/1 [door docent op te nemen op elk voorblad van tentamens] Integriteitscode voor studenten bij toetsen op afstand De Radboud Universiteit wil bijdragen aan een gezonde en vrije wereld met gelijke kansen voor iedereen. Zij leidt daartoe studenten op tot gewetensvolle, betrokken, kritische en zelfbewuste academici. Daarbij hoort een houding van betrouwbaarheid en integriteit. Aan de Radboud Universiteit gaan wij er daarom van uit dat je aan je studie bent begonnen, omdat je daadwerkelijk kennis wilt opdoen en je inzicht en vaardigheden eigen wilt maken. Het is essentieel voor de opbouw van je opleiding (en daarmee voor je verdere loopbaan) dat jij de kennis, inzicht en vaardigheden bezit die getoetst worden. Wij verwachten dus dat je dit tentamen op eigen kracht maakt, zonder gebruik te maken van hulpbronnen, tenzij dit is toegestaan door de examinator. Wij vertrouwen erop dat je tijdens deelname aan dit tentamen, je houdt aan de geldende wet- en regelgeving, en geen identiteitsfraude pleegt, je niet schuldig maakt aan plagiaat of andere vormen van fraude en andere studenten niet frauduleus bijstaat. Verklaring fraude en plagiaat tentamens Faculteit der Letteren Door dit tentamen te maken en in te leveren verklaar ik dit tentamen zelf en zonder hulp van anderen gemaakt te hebben. Ik verklaar bovendien dat ik voor dit tentamen geen gebruik heb gemaakt van papieren en/of digitale bronnen, notities, opnames of welke informatiedragers ook (tenzij nadrukkelijk vooraf door de examinator toegestaan) en geen overleg heb gepleegd met andere personen. -

View Early Day Motions PDF File 0.12 MB

Published: Thursday 18 March 2021 Early Day Motions tabled on Wednesday 17 March 2021 Early Day Motions (EDMs) are motions for which no days have been fixed. The number of signatories includes all members who have added their names in support of the Early Day Motion (EDM), including the Member in charge of the Motion. EDMs and added names are also published on the EDM database at www.parliament.uk/edm [R] Indicates that a relevant interest has been declared. New EDMs 1655 Sandra Stewart, 40 years' commitment to the Scottish Fire and Rescue Service Tabled: 17/03/21 Signatories: 1 Patricia Gibson That this House congratulates Sandra Stewart on her 40 year anniversary as a member of the Scottish Fire and Rescue Service; understands that the Admin Team Leader joined the Strathclyde Fire Brigade immediately upon leaving school, and now provides admin support to more than forty fire stations across Ayrshire and Dumfries & Galloway from the area HQ in Ardrossan, North Ayrshire; and thanks her for the dedication and commitment she has shown to the communities she has served throughout her years in her vital work, and hugely appreciates her ongoing service. 1656 Undercover Policing Inquiry Tabled: 17/03/21 Signatories: 5 Richard Burgon Ms Diane Abbott Liz Saville Roberts Chris Stephens Caroline Lucas That this House notes the ongoing independent public Undercover Policing Inquiry, set up to investigate undercover policing in England and Wales since 1968; recognises the concerns raised by Non State Non Police Core Participants (NSNPCPs) and interested -

OUR OFFICERS CHAIR Jim Shannon MP CO-CHAIR Baroness Berridge

THE ALL PARTY PARLIAMENTARY GROUP FOR INTERNATIONAL FREEDOM OF RELIGION OR BELIEF 2 MAY 2017 OUR OFFICERS CHAIR Jim Shannon MP CO-CHAIR Baroness Berridge Gavin Shuker MP VICE-CHAIRS Lord Singh of Wimbledon Baroness Cox TREASURER Jeremy Lefroy MP SECRETARY Dr Eilidh Whiteford MP George Howarth MP OUR MEMBERS Tasmina Ahmed-Sheikh MP Lord Alton Sir David Amess MP Edward Argar MP Steve Baker MP Baroness Berridge Ian Blackford MP Lord Boateng Sir Peter Bottomley MP Tom Brake MP Julian Brazier MP Baroness Brinton Alan Brown MP Fiona Bruce MP Richard Burden MP David Burrowes MP Gregory Campbell MP Lord Clarke of Hampstead Lord Collins Lord Cotter Bishop of Coventry Baroness Cox Geoffrey Cox MP Jon Cruddas MP Nic Dakin MP Bishop of Derby Nigel Dodds MP Sir Jeffrey Donaldson MP Stephen Doughty MP Mark Durkan MP Jonathan Edwards MP Tom Elliott MP Nigel Evans MP Margaret Ferrier MP Robert Flello MP Mike Gapes MP Patricia Gibson MP Lord Gordon Richard Graham MP Peter Grant MP Chris Green MP Fabian Hamilton MP Sharon Hodgson MP George Howarth MP Sir Gerald Howarth MP Dr Rupa Huq MP Jeremy Lefroy MP Dr Julian Lewis MP Kerry McCarthy MP Lord McColl Siobhain McDonagh MP Liz McInnes MP Anne McLaughlin MP John McNally MP Rob Marris MP Chris Matheson MP Mark Menzies MP Sarah Newton MP Lord Oates Brendan O’Hara MP Kirsten Oswald MP Ian Paisley MP Lord Parekh Bishop of Peterborough Steve Pound MP Mark Pritchard MP Gavin Robinson MP Andrew Rosindell MP David Rutley MP Bishop of St Albans Liz Saville Roberts MP Lord Selkirk Jim Shannon MP Baroness Sherlock Gavin Shuker MP David Simpson MP Lord Singh of Wimbledon Caroline Spelman MP Andrew Stephenson MP Gary Streeter MP Wes Streeting MP Lord Suri Derek Thomas MP Gareth Thomas MP Stephen Timms MP Michael Tomlinson MP Tom Tugendhat MP Valerie Vaz MP Catherine West MP Dr Eilidh Whiteford MP Sammy Wilson MP Bishop of Worcester . -

Scottish Mps 2015

Scotland Members of Parliament 2015 Conservatives – David Mundell - Dumfriesshire, Clydesdale and Tweeddale Liberal Democrats – Alistair Carmichael, Orkney and Shetland Labour – Ian Murray, Edinburgh South Scottish National Party Tasmina Ahmed-Sheikh Ochil & South Perthshire Richard Arkless Dumfries & Galloway Hannah Bardell Livingston Mhairi Black Paisley & Renfrewshire South Ian Blackford Ross, Skye & Lochaber Kirsty Blackman Aberdeen North Phil Boswell Coatbridge, Chryston & Bellshill Deidre Brock Edinburgh North & Leith Alan Brown Kilmarnock & Loudoun Lisa Cameron East Kilbride, Strathaven & Lesmahagow Douglas Chapman Dunfermline & West Fife Joanna Cherry Edinburgh South West Ronnie Cowan Inverclyde Angela Crawley Lanark & Hamilton East Martyn Day Linlithgow & East Falkirk Martin Docherty West Dunbartonshire Stuart Donaldson West Aberdeenshire & Kincardine Marion Fellows Motherwell & Wishaw Margaret Ferrier Rutherglen & Hamilton West Stephen Gethins North East Fife Patricia Gibson North Ayrshire & Arran Patrick Grady Glasgow North Peter Grant Glenrothes Neil Gray Airdrie & Shotts Drew Hendry Inverness, Nairn, Badenoch & Strathspey Stewart Hosie Dundee East George Kerevan East Lothian Calum Kerr Berwickshire, Roxburgh & Selkirk County Chris Law Dundee West Angus MacNeil Na H-Eileanan An Iar Callum McCaig Aberdeen South Stewart McDonald Glasgow South Stuart McDonald Cumbernauld, Kilsyth & Kirkintilloch East Natalie McGarry Glasgow East Anne McLaughlin Glasgow North East John McNally Falkirk Paul Monaghan Caithness, Sutherland & Easter -

The General Election Breadline Battleground

The General Election Breadline Battleground www.centreforsocialjustice.org.uk Contents Introduction 1 Identifying the breadline battleground – the challenge facing all political parties… 3 Overview: 3 Methodology - how we have created the breadline battleground: 4 What these voters think about the political parties: Do they really care? 4 What party will low-income voters vote for? 5 Do they care about me? 6 Appendix 1: 7 1a. The 100 Most Marginal Constituencies: 7 Appendix 2: Labour targets for a majority of 50 8 Most marginal constituencies – England 11 Most marginal constituencies – Wales 12 Most marginal constituencies – Scotland 13 Appendix 2: 14 Methodological statements on calculating the breadline battleground: 14 Appendix 3: 16 Survey results for low-income voters 16 Introduction In a recent survey of low-income voters commissioned by the Centre for Social Justice (CSJ) almost 8 in 10 (78 per cent) voters living on the lowest incomes have never met or spoken to their local MP. Over half of these voters also told us they hadn’t heard from any of the parties in the last year, despite candidates gearing up for a general election campaign. It is probably not surprising that 60 per cent of these forgotten voters told us that “no political party really cares about helping people like me”. The coming general election needs to be about more than Brexit if it is going to address the issues that face low-income Britain. Whether you voted leave or remain in 2016, our analysis shows that any political party will struggle to win a working majority if they fail to connect with the poorest voters across Britain and demonstrate that tackling poverty is a top priority. -

Finance Bill, As Amended

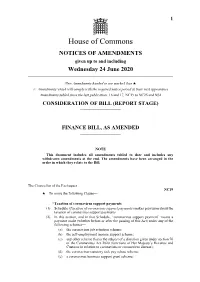

1 House of Commons NOTICES OF AMENDMENTS given up to and including Wednesday 24 June 2020 New Amendments handed in are marked thus Amendments which will comply with the required notice period at their next appearance Amendments tabled since the last publication: 16 and 17, NC19 to NC25 and NS1 CONSIDERATION OF BILL (REPORT STAGE) FINANCE BILL, AS AMENDED NOTE This document includes all amendments tabled to date and includes any withdrawn amendments at the end. The amendments have been arranged in the order in which they relate to the Bill. The Chancellor of the Exchequer NC19 To move the following Clause— “Taxation of coronavirus support payments (1) Schedule (Taxation of coronavirus support payments) makes provision about the taxation of coronavirus support payments. (2) In this section, and in that Schedule, “coronavirus support payment” means a payment made (whether before or after the passing of this Act) under any of the following schemes— (a) the coronavirus job retention scheme; (b) the self-employment income support scheme; (c) any other scheme that is the subject of a direction given under section 76 of the Coronavirus Act 2020 (functions of Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs in relation to coronavirus or coronavirus disease); (d) the coronavirus statutory sick pay rebate scheme; (e) a coronavirus business support grant scheme; 2 Consideration of Bill (Report Stage): 24 June 2020 Finance Bill, continued (f) any scheme specified or described in regulations made under this section by the Treasury. (3) The Treasury may by regulations make provision about the application of Schedule (Taxation of coronavirus support payments) to a scheme falling within subsection (2)(c) to (f) (including provision modifying paragraph 8 of that Schedule so that it applies to payments made under a coronavirus business support grant scheme).