CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL Mgnrhly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Corinthian Lord's Supper Could Be the Adoption of Greco- Roman Meal Tradition Into the Church Meal

The American Journal of Biblical Theology Volume 20(7), February 17, 2019 Dr. George Philip The Corinthian Lord’s Supper: Paul’s Critique of the Greco-Roman Meal Tradition Abstract: The predominance of various social groups in the Corinthian church created social tension and disharmony in relation to the Lord's Supper. Recent studies on the Lord's Supper take account of the Corinthian social groups but fail to connect it with the wider Greco-Roman Meal tradition of the day and its ramifications. Paul identified the root cause of disharmony as the irrational adoption of the external characteristics of the Greco-Roman Meal tradition such as social ranking, display of honour, social identity and social differentiation. Paul critically looked at the influence of the Greco-Roman Meal tradition and corrected the Corinthian Lord’s Supper by appealing to the Last Supper tradition. Introduction The practice of common meal was an important social institution in the early Christian church. When a group of people eat together, they form a social order by which they consolidate their group identity and follow certain social customs. The concern behind this assumption is that eating food is a social act, done in the company of others and that such table fellowship has the potential to build links among those who eat together. Peter Garnsey observes, Outside the home, commensality demonstrated and confirmed the membership and solidarity of the group, paraded the status of the group vis-a-vis outsiders, and set out the hierarchies that existed both in the society at large and within the group itself.1 Corinthian meals in general and the Lord’s Supper (1Cor. -

Tuomas Havukainen: the Quest for the Memory of Jesus

Tuomas Havukainen The Quest for the Memory of Jesus: A Havukainen Tuomas Viable Path or a Dead End? Tuomas Havukainen | This study is focused on the active international or a Dead End? Path Viable the Memory Quest for The of Jesus: A field of study in which various theories of mem- ory (e.g. social/collective memory and individual The Quest for the Memory of Jesus: memory) and ancient media studies (e.g. study A Viable Path or a Dead End? of oral tradition and history) are applied to historical Jesus research. The main purpose of the dissertation is to study whether the memory approach constitutes a coherent methodological school of thought. The dissertation discusses in what ways the memory approach distinguishes itself from earlier research and whether one can speak of a new beginning in historical Jesus research. A central focus of the study is the research-historical discussion on the nature and processes of the transmission of the Jesus tradi- tions in early Christianity, which is a significant research problem for both earlier historical Jesus research and the memory approach. | 2017 9 789517 658812 Åbo Akademi University Press | ISBN 978-951-765-881-2 Tuomas Havukainen (born 1988) Master of Theology (MTh) 2012, University of Wales Cover Photo: by Patrik Šlechta, September 11, 2014, from Pixabay.com. Photo licensed under CC0 1.0 https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ https://pixabay.com/en/israel-path-dune-desert-499050/ Åbo Akademi University Press Tavastgatan 13, FI-20500 Åbo, Finland Tel. +358 (0)2 215 3478 E-mail: [email protected] Sales and distribution: Åbo Akademi University Library Domkyrkogatan 2–4, FI-20500 Åbo, Finland Tel. -

Pauline Churches Or Early Christian Churches?

PAULINE CHURCHES OR EARLY CHRISTIAN CHURCHES ? * UNITY , DISAGREEMENT , AND THE EUCHARIST . David G. Horrell University of Exeter, UK I: Introduction Given the prominence of the Eucharist as a facet of contemporary church practice and a stumbling block in much ecumenical discussion, it is unsurprising that it is a topic, like other weighty theological topics, much explored in NT studies. These studies have, over the years, ranged across many specific topics and questions, including: the original form of the eucharistic words of Jesus; the original character of the Last Supper (Was it a passover meal?); the original form or forms of the early Christian Eucharist and its subsequent liturgical development. Some studies have also addressed broader issues, such as the theological and eschatological significance of Jesus’s table fellowship, and the parallels between early Christian meals and the dining customs of Greco-Roman antiquity. 1 Indeed, one of the key arguments of Dennis Smith’s major study of early Christian meals is to stress how unsurprising it is that the early Christians met over a meal: ‘Early Christians met at a meal because that is what groups in the ancient world did. Christians were simply following a pattern found throughout their world.’ Moreover, Smith proposes, the character of the early Christian meal is again simply explained: ‘Early Christians celebrated a meal based on the banquet model found throughout their world.’ 2 * Financial support to enable my participation at the St Petersburg symposium was provided by the British Academy and the Hort Memorial Fund (Faculty of Divinity, University of Cambridge) and I would like to express my thanks for that support. -

Robert W. Funk and the German Theological Tradition

From: The Fourth R, volume 19, number 2, March –April 2006 (“The Life & Legacy of Robert W. Funk”), pp. 7, 20. Robert W. Funk and the German Theological Tradition Gerd Lüdemann Bob Funk did his graduate work at Vanderbilt University, completing it in 1953 with his Ph. D. thesis, The Syntax of the Greek Article: Its Importance for Critical Pauline Problems. His dissertation supervisor, Kendrick Grobel (1908–65), introduced the young student––whose rejection of simplistic Christian creeds led him to scholarship1––to the world of biblical criticism, which at the time was largely shaped by German scholars. Grobel’s active role in this movement began in 1934 with his dissertation, “Form Criticism and Synoptic Source Analysis,”2 prepared under the supervision of the famous form critic Martin Dibelius at the University of Heidelberg.3 Grobel also translated Rudolf Bultmann’s “Theology of the New Testament” (1951, 1955), and in the early fifties organized a U. S. lecture tour by Rudolf Bultmann. The young Bob Funk must have listened attentively when the famous German exegete delivered the Cole Lectures at Vanderbilt Divinity School. No wonder, then, that he spent the first twenty years of his scholarly career in developing and transmitting the philological, linguistic, historical-critical, and theological skills he acquired from German New Testament scholarship. He actively participated in conferences on New Testament hermeneutics at Drew University and later at Vanderbilt, where in 1966 he was called to succeed his former mentor, Kendrick Grobel. Along with similarly oriented Americans James M. Robinson, Van A. Harvey, and Schubert Ogden, he translated Bultmann’s essays and joined their author’s German students Gerhard Ebeling and Ernst Fuchs in developing Bultmann’s ideas. -

Implications of Recent Exegetical Studies for the Doctrine of the Lord's Supper: a Survey of the Literature

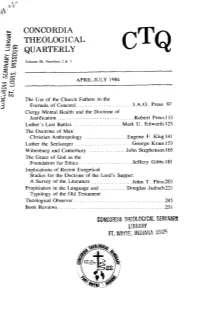

CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL QUARTERLY Volume 48, Iriumbers 2 & 1 APRIL-JULY 1984 The Use of the Church Fathers in the Formula of Concord .....................J .A-0. Preus 97 Clergy Mental Health and the Doctrine of Justification ........................... .Robert Preus 113 Luther's Last Battles ................. .Mark U. Edwards 125 The Doctrine of Man: Christian Anthropology ................Eugene F. Klug 14.1 Luther the Seelsorger- ..................... George Kraus 153 Wittenburg and Canterbury ............. .John Stephenson 165 The Grace of God as the Foundation for Ethics ...................Jeffery Gibbs 185 Implications of Recent Exegetical Studies for the Doctrine of the Lord's Supper: A Survey of the Literature .........oh T. Pless203 Propitiation in the Language and ......... .Douglas Judisch221 Typology of the Old Testament Theological Observer .................................245 Book Reviews ...................................... .251 CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL SEMINAR1 Lt BRPIRY n. WAYriL INDfAN:! -1S82F., of ecent Exegetical Studies for the Doctrine of the ord’s Supper: Survey of the Literature John T. Hess Confessional Lutheran theology rightly insists that the doc- trine of the Lord’s Supper must be firmly grounded on the scriptural texts. It is the word of God that discloses the meaning of the sacrament. The question raised for contemporary Lutheranism focuses our attention on this central issue: “What do the Scriptures actually tell us about the Lord’s Supper?” This question calls attention to the fact that theology cannot be divided into neat categories of exegetical studies, dogmatics, historical studies, and practical theology which are unrelated to each other. In fact, when we look at the doctrine of the Lord’s Supper we see the complexity of the inter-relatedness of the various theological disciplines. -

The Time of the Reign of Christ in 1 Corinthians 15:20-28 in Light of Early Christian Session Theology

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 1997 The Time of the Reign of Christ in 1 Corinthians 15:20-28 in Light of Early Christian Session Theology Roger P. Lucas Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Biblical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Lucas, Roger P., "The Time of the Reign of Christ in 1 Corinthians 15:20-28 in Light of Early Christian Session Theology" (1997). Dissertations. 88. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/88 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter free, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

HISTORICAL JESUS, QUEST of 1. the Original Quest

HISTORICAL JESUS, QUEST OF Christianity might well have ended then but for the ingenuity and duplicity of the Joel B. Green, Scot McKnight and I. Howard Marshall, Dictionary of Jesus and the disciples. When it became clear that there would be no general persecution, they Gospels (Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 1992), 326-341. This is printed from emerged from hiding, proclaiming that Jesus had been raised from the dead and would Logos Bible Software, so the pagination is slightly different than the physical book. return to establish the promised kingdom. Eschatology was thus the key to understanding both Jesus and the disciples, but in both cases it is mistaken. Jesus The idea of the quest of the historical Jesus gained currency through Albert Schweitzer’s wrongly believed that God would establish his king dom on earth through him; the The Quest of the Historical Jesus: A Critical Study of its Progress from Reimarus to disciples were guilty of encouraging false expectations of the coming kingdom. Wrede (1910). Schweitzer’s original German title Von Reimarus zu Wrede. Eine The Wolfenbüttel Fragments provoked numerous replies. The weightiest came from Geschichte der Leben-Jesu-Forschung [From Reimarus to Wrede. A History of Research the leading biblical scholar of the day and founder of “liberal theology,” J. S. Semler into the Life of Jesus] (1906) suggested a history of biographical research. The English (1725–91). Semler’s Answer to the Fragments (1791) was virtually a line-by-line title bestowed added drama to Schweitzer’s narrative of the numerous efforts from the refutation, written from the standpoint of a moderate orthodoxy. -

Studies in Early Christianity

Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament Herausgegeben von Jörg Frey Mitherausgeber/Associate Editors Friedrich Avemarie • Judith Gundry-Volf Martin Hengel • Otfried Hofius • Hans-Josef Klauck 161 ARTI BUS François Bovon Studies in Early Christianity Mohr Siebeck FRANÇOIS BOVON: Studies of Theology in Lausanne, Basel, Gôttingen, Strasbourg and Edin- bourgh; 1965 Dr. theol.; 1967-1993 Professor at the University of Geneva; since 1993 Frothin- gham Professor of the History of Religion at Harvard University; honorary professor of the University of Geneva; Dr. honoris causa of the University of Uppsala. ISBN 3-16-147079-6 ISSN 0512-1604 (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament) Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de. © 2003 by J.C.B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), P.O. Box 2040, D-72010 Tübingen. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by co- pyright law) without the publisher's written permission. This applies particularly to reproduc- tions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was printed by Guide-Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper and bound by Buchbin- derei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany Preface Circumstances and inclination have driven me to write and publish articles. The papers that are collected and reprinted here are the result of academic lectures, contributions to symposia, Festschriften and special investigations. With the ex- ception of a few bibliographical modifications, they are published here as they ap- peared the first time. At the suggestion of Dr. -

Jews and Protestants

Jews and Protestants Jews and Protestants From the Reformation to the Present Edited by Irene Aue-Ben-David, Aya Elyada, Moshe Sluhovsky and Christian Wiese Supported by the I-CORE Program of the Planning and Budgeting Committee and The Israel Science Foundation (grant No. 1798/12) Die freie Verfügbarkeit der E-Book-Ausgabe dieser Publikation wurde ermöglicht durch den Fachinformationsdienst Jüdische Studien an der Universitätsbibliothek J. C. Senckenberg Frankfurt am Main und 18 wissenschaftliche Bibliotheken, die die Open-Access-Transformation in den Jüdischen Studien unterstützen. ISBN 978-3-11-066108-8 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-066471-3 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-066486-7 Despite careful production of our books, sometimes mistakes happen. Unfortunately, the CC license was not included in the original publication. This has been corrected. We apologize for the mistake. Dieses Werk ist lizenziert unter der Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Lizenz. Weitere Informationen finden Sie unter http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Das E-Book ist als Open-Access-Publikation verfügbar über www.degruyter.com, https://www.doabooks.org und https://www.oapen.org. Library of Congress Control Number: 2019955542 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2020, Aue-Ben-David et al., published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover image: ulimi / DigitalVision Vectors / gettyimages.de Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Open-Access-Transformation in den Jüdischen Studien Open Access für exzellente Publikationen aus den Jüdischen Studien: Dies ist das Ziel der gemeinsamen Initiative des Fachinformationsdiensts Jüdische Studien an der Universitäts- bibliothek J. -

Searching for the Historical Jesus: Does History Repeat Itself? F

Searching for the Historical Jesus: Does History Repeat Itself? F. David Farnell A wise old saying has warned, "Those who do not learn from the lessons of history are doomed to repeat them." Does history repeat itself? Pondering this question is important for current evangelical Gospel discussions, especially in reference to modem Gospel research. In terms of searching for "the historical Jesus," history has indeed repeated itself through the First and Second Quest and is threatening to do so again in the contemporary Third Quest. Below it is argued that based on the lessons of the first two quests, evangelicals should be leery of involvement in the Third Quest lest history repeat itself yet again. 1 The Consistent Testimony of the Orthodox Church for 1700 Years From the nascent beginnings of the church until the A.D. 17th century, orthodox Christians held that the four canonical Gospels, Matthew, Luke, Mark and John were historical, biographical, albeit selective (cf. John 20:30-31) eyewitness accounts of Jesus' life written by the men whose names were attached to them from the beginning.2 These Gospels are virtually the only source for our knowledge of the acts and teachings of Jesus. 3 The Gospels were considered by the Church as the product of Spirit-energized minds (John 14:26; 16:13; 1 John 4:4) to give the true presentation of Jesus' life and work for the thirty-plus years that He lived on the earth. The consistent, as well as persistent, testimony expressed in early church history was that the Apostle Matthew, also known as Levi, -

Concordia Theological Monthly

CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL MONTHLY The Will of God in the Life of a Christian EUGENE F. KLUG The Word of God in the Theology of Lutheran Orthodoxy ROBERT D. PREUS Homiletics Theological Observer Book Review VOL.xxxm August 1962 No.8 BOOK REVIEW All books reviewed in this periodical may be procured from 01' through C011cordia Pub lishing House, 3558 South Jefferson Avenue, St. Louis 18, Missouri. EVEN UNTO DEATH: THE HEROIC reading material for the smdent who is being WITNESS OF THE SIXTEENTH-CEN introduced to the history of the West. Cor TURY ANABAPTISTS. By John Chris nell's attempt to provide interestingly written tian Wenger. Richmond, Va.: John Knox monographs by authorities on given periods Press, 1961. 127 pages. Cloth. $2.50. has scored again. Heirs of the Roman Em· Wenger provides a good introduction to pire is excellent for the transition from Rome some 16th-century leaders of the "Left Wing to the Middle Ages no less than for its really Reformation" and their teachings. He has adequate treatment of the religion factors. examined the letters, tracts, books, court WALTER W . OETTING testimonies, and confessional writings of these "witnesses." Their attimdes toward the A HISTORY OF THE EARLY CHURCH. Bible, their doctrine of the church and the By Hans Lietzmann. Translated by Ber sacraments, and their ethics are given special tram Lee Woolf. Cleveland: The World attention. The Complete Writings of Menno Publishing Company, 1961. Four volumes Simons are cited most frequently. There is in two. 1182 pages. Paper. $4.50 the set. only one reference to the volume edited by Lietzmann's standard four-volume smdy, G. -

The Muratorian Fragment: the State of Research

JETS 57/2 (2014) 231–64 THE MURATORIAN FRAGMENT: THE STATE OF RESEARCH ECKHARD J. SCHNABEL* The fragmentary document known as “Canon Muratori” contains the oldest list of books of the NT. This essay will present the state of research regarding the Fragment, with particular attention to its date as wEll as its historical and theologi- cal significance. I. THE FRAGMENT The Muratorian Fragment consists of 85 lines; the beginning and probably the end are missing. The Fragment was discovered by Ludovico Antonio Muratori (1672–1750), an archivist and librarian at Modena, in the year 1700 in a manuscript in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan (Cod. Ambr. I 101 sup.), consisting of 76 leaves of coarse parchment. MuratOri publishEd thE FragmEnt in 1740 in thE third volume of his six-volume collection OF essays entitled Antiquitates italicæ mediiævi, in Dissertatio XLIII (cOls. 807–880) undEr thE hEading “De Literarum Statu, neglectu, & cultura in Italia post Barbaros in eam invEctos usque ad Annum Christi Millesi- mum Centesimum.”1 The manuscript originally bElonged to thE mOnastery at BobbiO in thE TrEb- bia River valley southwest of Piacenza in northern Italy. The manuscript contains a statement of Ownership by thE BObbiO mOnastEry: liber sti columbani de bobbio/Iohis grisostomi.2 ThE manuscript cOntains sEvEral thEOlogical treatisEs of thrEE thEOlogians * Eckhard J. SchnabEl is Mary F. ROckEFEllEr Distinguished Professor of NT Studies at Gordon- Conwell Theological Seminary, 130 EssEx StrEEt, SOuth HamiltOn, MA 01982. 1 LudOvicO AntOniO MuratOri, “DE LitErarum Statu, nEglEctu, & cultura in Italia pOst BarbarOs in eam invectos usquE ad Annum Christi Millesimum Centesimum,” in Antiquitates italicæ mediiævi: sive disser- tationes de moribus, ritibus, religione, regimine, magistratibus, legibus, studiis literarum, artibus, lingua, militia, nummis, principibus, libertate, servitute, fœderibus, aliisque faciem & mores italici populi referentibus post declinationem Rom.