Oligodendroglioma & Oligoastrocytoma ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

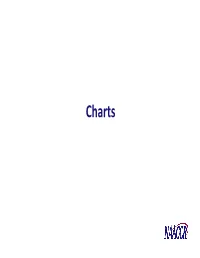

Charts Chart 1: Benign and Borderline Intracranial and CNS Tumors Chart

Charts Chart 1: Benign and Borderline Intracranial and CNS Tumors Chart Glial Tumor Neuronal and Neuronal‐ Ependymomas glial Neoplasms Subependymoma Subependymal Giant (9383/1) Cell Astrocytoma(9384/1) Myyppxopapillar y Desmoplastic Infantile Ependymoma Astrocytoma (9412/1) (9394/1) Chart 1: Benign and Borderline Intracranial and CNS Tumors Chart Glial Tumor Neuronal and Neuronal‐ Ependymomas glial Neoplasms Subependymoma Subependymal Giant (9383/1) Cell Astrocytoma(9384/1) Myyppxopapillar y Desmoplastic Infantile Ependymoma Astrocytoma (9412/1) (9394/1) Use this chart to code histology. The tree is arranged Chart Instructions: Neuroepithelial in descending order. Each branch is a histology group, starting at the top (9503) with the least specific terms and descending into more specific terms. Ependymal Embryonal Pineal Choro id plexus Neuronal and mixed Neuroblastic Glial Oligodendroglial tumors tumors tumors tumors neuronal-glial tumors tumors tumors tumors Pineoblastoma Ependymoma, Choroid plexus Olfactory neuroblastoma Oligodendroglioma NOS (9391) (9362) carcinoma Ganglioglioma, anaplastic (9522) NOS (9450) Oligodendroglioma (9390) (9505 Olfactory neurocytoma Ganglioglioma, malignant (()9521) anaplastic (()9451) Anasplastic ependymoma (9505) Olfactory neuroepithlioma Oligodendroblastoma (9392) (9523) (9460) Papillary ependymoma (9393) Glioma, NOS (9380) Supratentorial primitive Atypical EdEpendymo bltblastoma MdllMedulloep ithliithelioma Medulloblastoma neuroectodermal tumor tetratoid/rhabdoid (9392) (9501) (9470) (PNET) (9473) tumor -

Paraganglioma (PGL) Tumors in Patients with Succinate Dehydrogenase-Related PCC–PGL Syndromes: a Clinicopathological and Molecular Analysis

T G Papathomas and others Non-PCC/PGL tumors in the SDH 170:1 1–12 Clinical Study deficiency Non-pheochromocytoma (PCC)/paraganglioma (PGL) tumors in patients with succinate dehydrogenase-related PCC–PGL syndromes: a clinicopathological and molecular analysis Thomas G Papathomas1, Jose Gaal1, Eleonora P M Corssmit2, Lindsey Oudijk1, Esther Korpershoek1, Ketil Heimdal3, Jean-Pierre Bayley4, Hans Morreau5, Marieke van Dooren6, Konstantinos Papaspyrou7, Thomas Schreiner8, Torsten Hansen9, Per Arne Andresen10, David F Restuccia1, Ingrid van Kessel6, Geert J L H van Leenders1, Johan M Kros1, Leendert H J Looijenga1, Leo J Hofland11, Wolf Mann7, Francien H van Nederveen12, Ozgur Mete13,14, Sylvia L Asa13,14, Ronald R de Krijger1,15 and Winand N M Dinjens1 1Department of Pathology, Josephine Nefkens Institute, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center, PO Box 2040, 3000 CA Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2Department of Endocrinology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden,The Netherlands, 3Section for Clinical Genetics, Department of Medical Genetics, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway, 4Department of Human and Clinical Genetics, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands, 5Department of Pathology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands, 6Department of Clinical Genetics, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 7Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, University Medical Center of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, Mainz, Germany, 8Section for Specialized Endocrinology, -

Ambient Mass Spectrometry for the Intraoperative Molecular Diagnosis of Human Brain Tumors

Ambient mass spectrometry for the intraoperative molecular diagnosis of human brain tumors Livia S. Eberlina, Isaiah Nortonb, Daniel Orringerb, Ian F. Dunnb, Xiaohui Liub, Jennifer L. Ideb, Alan K. Jarmuscha, Keith L. Ligonc, Ferenc A. Joleszd, Alexandra J. Golbyb,d, Sandro Santagatac, Nathalie Y. R. Agarb,d,1, and R. Graham Cooksa,1 aDepartment of Chemistry and Center for Analytical Instrumentation Development, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907; and Departments of bNeurosurgery, cPathology, and dRadiology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115 Edited by Jack Halpern, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, and approved December 5, 2012 (received for review September 11, 2012) The main goal of brain tumor surgery is to maximize tumor resection at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH), created an opportu- while preserving brain function. However, existing imaging and nity for collecting information about the extent of tumor resection surgical techniques do not offer the molecular information needed during surgery (5, 6). Although brain tumor resection typically to delineate tumor boundaries. We have developed a system to requires multiple hours, intraoperative MRI can be completed rapidly analyze and classify brain tumors based on lipid information and information evaluated within an hour. However, MRI has acquired by desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry limited ability to distinguish residual tumor from surrounding (DESI-MS). In this study, a classifier was built to discriminate gliomas normal brain (9). In consequence, there is a need for more de- and meningiomas based on 36 glioma and 19 meningioma samples. tailed molecular information to be acquired on a timescale closer The classifier was tested and results were validated for intraoper- to real time than can be supplied by MRI. -

Central Neurocytoma SNP Array Analyses, Subtel FISH, and Review

Pathology - Research and Practice 215 (2019) 152397 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Pathology - Research and Practice journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/prp Case report Central neurocytoma: SNP array analyses, subtel FISH, and review of the T literature Caroline Sandera,1, Marco Wallenborna,b,1, Vivian Pascal Brandtb, Peter Ahnertc, Vera Reuscheld, ⁎ Christan Eisenlöffele, Wolfgang Kruppa, Jürgen Meixensbergera, Heidrun Hollandb, a Dept. of Neurosurgery, University of Leipzig, Liebigstraße 26, 04103 Leipzig, Germany b Saxonian Incubator for Clinical Translation, University of Leipzig, Philipp-Rosenthal Str. 55, 04103 Leipzig, Germany c Institute for Medical Informatics, Statistics and Epidemiology, University of Leipzig, Haertelstraße 16-18, 04107 Leipzig, Germany d Dept. of Neuroradiology, University of Leipzig, Liebigstraße 22a, 04103 Leipzig, Germany e Dept. of Neuropathology, University of Leipzig, Liebigstraße 26, 04103 Leipzig, Germany ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The central neurocytoma (CN) is a rare brain tumor with a frequency of 0.1-0.5% of all brain tumors. According Central neurocytoma to the World Health Organization classification, it is a benign grade II tumor with good prognosis. However, Cytogenetics some CN occur as histologically “atypical” variant, combined with increasing proliferation and poor clinical SNP array outcome. Detailed genetic knowledge could be helpful to characterize a potential atypical behavior in CN. Only FISH few publications on genetics of CN exist in the literature. Therefore, we performed cytogenetic analysis of an intraventricular neurocytoma WHO grade II in a 39-year-old male patient by use of genome-wide high-density single nucleotide polymorphism array (SNP array) and subtelomere FISH. Applying these techniques, we could detect known chromosomal aberrations and identified six not previously described chromosomal aberrations, gains of 1p36.33-p36.31, 2q37.1-q37.3, 6q27, 12p13.33-p13.31, 20q13.31-q13.33, and loss of 19p13.3-p12. -

A Case of Mushroom‑Shaped Anaplastic Oligodendroglioma Resembling Meningioma and Arteriovenous Malformation: Inadequacies of Diagnostic Imaging

EXPERIMENTAL AND THERAPEUTIC MEDICINE 10: 1499-1502, 2015 A case of mushroom‑shaped anaplastic oligodendroglioma resembling meningioma and arteriovenous malformation: Inadequacies of diagnostic imaging YAOLING LIU1,2, KANG YANG1, XU SUN1, XINYU LI1, MINGHAI WEI1, XIANG'EN SHI2, NINGWEI CHE1 and JIAN YIN1 1Department of Neurosurgery, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Dalian Medical University, Dalian, Liaoning 116044; 2Department of Neurosurgery, Affiliated Fuxing Hospital, The Capital University of Medical Sciences, Beijing 100038, P.R. China Received December 29, 2014; Accepted June 29, 2015 DOI: 10.3892/etm.2015.2676 Abstract. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the most tomas (WHO IV) (2). The median survival times of patients widely discussed and clinically employed method for the with WHO II and WHO III oligodendrogliomas are 9.8 and differential diagnosis of oligodendrogliomas; however, 3.9 years, respectively (1,2), and 6.3 and 2.8 years, respec- MRI occasionally produces unclear results that can hinder tively, if mixed with astrocytes (3,4). Surgical excision and a definitive oligodendroglioma diagnosis. The present study postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy is the traditional therapy describes the case of a 34-year-old man that suffered from for oligodendroglioma; however, studies have observed that, headache and right upper‑extremity weakness for 2 months. among intracranial tumors, anaplastic oligodendrogliomas Based on the presurgical evaluation, it was suggested that the are particularly sensitive to chemotherapy, and the prognosis patient had a World Health Organization (WHO) grade II-II of patients treated with chemotherapy is more favorable glioma, meningioma or arteriovenous malformation (AVM), than that of patients treated with radiotherapy (5‑7). -

The New WHO Classification of Brain Tumors and Molecular Profiling in the Diagnosis of Gliomas

The New WHO Classification of Brain Tumors and Molecular Profiling in the Diagnosis of Gliomas Aivi Nguyen, MD Neuropathology Fellow Division of Neuropathology Center for Personalized Diagnosis (CPD) Glial neoplasms – infiltrating gliomas Astrocytic tumors • Diffuse astrocytoma II • Anaplastic astrocytoma III • Glioblastoma • Giant cell glioblastoma IV • Gliosarcoma Oligodendroglial tumors • Oligodendroglioma II • Anaplastic oligodendroglioma III Oligoastrocytic tumors • Oligoastrocytoma II • Anaplastic oligoastrocytoma III Courtesy of Dr. Maria Martinez-Lage 2 2016 3 The 2016 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system Louis et al., Acta Neuropathologica 2016 4 Talk Outline Genetic, epigenetic and metabolic changes in gliomas • Mechanisms/tumor biology • Incorporation into daily practice and WHO classification Penn’s Center for Personalized Diagnostics • Tests performed • Results and observations to date Summary 5 The 2016 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system Louis et al., Acta Neuropathologica 2016 6 Mechanism of concurrent 1p and 19q chromosome loss in oligodendroglioma lost FUBP1 CIC Whole-arm translocation Griffin et al., Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology 2006 7 Oligodendroglioma: 1p19q co-deletion Since the 1990s Diagnostic Prognostic Predictive Li et al., Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2014 8 Mutations of Selected Genes in Glioma Subtypes GBM Astrocytoma Oligodendroglioma Oligoastrocytoma Killela et al., PNAS 2013 9 Escaping Senescence Telomerase reverse transcriptase gene -

Malignant CNS Solid Tumor Rules

Malignant CNS and Peripheral Nerves Equivalent Terms and Definitions C470-C479, C700, C701, C709, C710-C719, C720-C725, C728, C729, C751-C753 (Excludes lymphoma and leukemia M9590 – M9992 and Kaposi sarcoma M9140) Introduction Note 1: This section includes the following primary sites: Peripheral nerves C470-C479; cerebral meninges C700; spinal meninges C701; meninges NOS C709; brain C710-C719; spinal cord C720; cauda equina C721; olfactory nerve C722; optic nerve C723; acoustic nerve C724; cranial nerve NOS C725; overlapping lesion of brain and central nervous system C728; nervous system NOS C729; pituitary gland C751; craniopharyngeal duct C752; pineal gland C753. Note 2: Non-malignant intracranial and CNS tumors have a separate set of rules. Note 3: 2007 MPH Rules and 2018 Solid Tumor Rules are used based on date of diagnosis. • Tumors diagnosed 01/01/2007 through 12/31/2017: Use 2007 MPH Rules • Tumors diagnosed 01/01/2018 and later: Use 2018 Solid Tumor Rules • The original tumor diagnosed before 1/1/2018 and a subsequent tumor diagnosed 1/1/2018 or later in the same primary site: Use the 2018 Solid Tumor Rules. Note 4: There must be a histologic, cytologic, radiographic, or clinical diagnosis of a malignant neoplasm /3. Note 5: Tumors from a number of primary sites metastasize to the brain. Do not use these rules for tumors described as metastases; report metastatic tumors using the rules for that primary site. Note 6: Pilocytic astrocytoma/juvenile pilocytic astrocytoma is reportable in North America as a malignant neoplasm 9421/3. • See the Non-malignant CNS Rules when the primary site is optic nerve and the diagnosis is either optic glioma or pilocytic astrocytoma. -

Meningioma ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

AMERICAN BRAIN TUMOR ASSOCIATION Meningioma ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ABOUT THE AMERICAN BRAIN TUMOR ASSOCIATION Meningioma Founded in 1973, the American Brain Tumor Association (ABTA) was the first national nonprofit advocacy organization dedicated solely to brain tumor research. For nearly 45 years, the ABTA has been providing comprehensive resources that support the complex needs of brain tumor patients and caregivers, as well as the critical funding of research in the pursuit of breakthroughs in brain tumor diagnosis, treatment and care. To learn more about the ABTA, visit www.abta.org. We gratefully acknowledge Santosh Kesari, MD, PhD, FANA, FAAN chair of department of translational neuro- oncology and neurotherapeutics, and Marlon Saria, MSN, RN, AOCNS®, FAAN clinical nurse specialist, John Wayne Cancer Institute at Providence Saint John’s Health Center, Santa Monica, CA; and Albert Lai, MD, PhD, assistant clinical professor, Adult Brain Tumors, UCLA Neuro-Oncology Program, for their review of this edition of this publication. This publication is not intended as a substitute for professional medical advice and does not provide advice on treatments or conditions for individual patients. All health and treatment decisions must be made in consultation with your physician(s), utilizing your specific medical information. Inclusion in this publication is not a recommendation of any product, treatment, physician or hospital. COPYRIGHT © 2017 ABTA REPRODUCTION WITHOUT PRIOR WRITTEN PERMISSION IS PROHIBITED AMERICAN BRAIN TUMOR ASSOCIATION Meningioma INTRODUCTION Although meningiomas are considered a type of primary brain tumor, they do not grow from brain tissue itself, but instead arise from the meninges, three thin layers of tissue covering the brain and spinal cord. -

Current Diagnosis and Treatment of Oligodendroglioma

Neurosurg Focus 12 (2):Article 2, 2002, Click here to return to Table of Contents Current diagnosis and treatment of oligodendroglioma HERBERT H. ENGELHARD, M.D., PH.D. Departments of Neurosurgery, Bioengineering, and Molecular Genetics, The University of Illinois at Chicago, Illinois Object. The strategies used to diagnose and treat oligodendroglial tumors have changed significantly over the past decade. The purpose of this paper is to review the topic of oligodendroglioma, emphasizing the new developments. Methods. Information was obtained by conducting a Medline search in which the term oligodendroglioma was used. Recent editions of standard textbooks were also studied. Because of tools such as magnetic resonance imaging, oligodendrogliomas are being diagnosed earlier, and they are being recognized more frequently histologically than in the past. Seizures are common in these patients. Functional mapping and image-guided surgery may now allow for a safer and more complete resection, especially when tumors are located in difficult areas. Genetic analysis and positron emission tomography may provide data that supplement the standard diagnostic tools. Unlike other low-grade gliomas, patients in whom residual or recurrent oligodendroglioma (World Health Organization Grade II) is present may respond to chemotherapy. Although postoperative radiotherapy prolongs survival of the patient, increasingly this therapeutic modality is being delayed until tumor recurrence, espe- cially if a gross-total tumor resection has been achieved. Oligodendrogliomas are the first type of brain tumor for which “molecular” characterization gives important information. The most significant finding is that allelic losses on chro- mosomes 1p and 19q indicate a favorable response to chemotherapy. Conclusions. Whereas surgery continues to be the primary treatment for oligodendroglioma, the scheme for post- operative therapy has shifted, primarily because of the lesion’s relative chemosensitivity. -

Primary Spinal Cord Oligodendroglioma: a Case Report and Review of the Literature Thara Tunthanathip* and Thakul Oearsakul

Tunthanathip and Oearsakul Chinese Neurosurgical Journal (2016) 2:2 DOI 10.1186/s41016-015-0021-4 CASE REPORT Open Access Primary spinal cord oligodendroglioma: a case report and review of the literature Thara Tunthanathip* and Thakul Oearsakul Abstract Background: Primary spinal cord oligodendroglioma is extremely rare. In an extensive review of this disease, 53 cases were reported. Furthermore, the authors summarize the characteristics of the primary spinal cord oligodendroglioma; chronological presentation , neurological imaging, treatment and the outcome obtained in the present case as well as review the literature. Case Presentation: A 46-year-old male who had progressive neck pain for a year. Magnetic resonance imaging showed an intramedullary mass from level C2 to T4. A radical resection was performed. Histology revealed oligodendroglioma. Thereafter, the patient was treated with adjuvant radiotherapy. A year later, tumor developed recurrence. The patinet died in 3 years and 6 months. Conclusions: The available data of this disease was limited. Base on 11 published papers and the present case, surgical resection is the treatment of choice although recurrence of the tumor tends to occur after partial resection with or without radiotherapy. From the literature, the management of the recurrent disease is still surgery. Moreover, Temozolomide may be an advantage in recurrent situations. Keywords: Oligodendroglioma, Spinal cord tumor, Intramedullary tumor, Treatment Background Pinpricked sensation was suspended deficits at C5-T1 Oligodendroglioma originates from oligodendrocyte, levels. Biceps, triceps and brachioradialis, knee and which is found in either the brain or spinal cord [1]. Achilles reflexes were 2+. Further, Hoffman reflexes This tumor is commonly found in the cerebral hemi- were absent. -

Molecular Subtypes of Anaplastic Oligodendroglioma: Implications for Patient Management at Diagnosis1

Vol. 7, 839–845, April 2001 Clinical Cancer Research 839 Molecular Subtypes of Anaplastic Oligodendroglioma: Implications for Patient Management at Diagnosis1 Yasushi Ino, Rebecca A. Betensky, without TP53 mutations, which are poorly responsive, ag- Magdalena C. Zlatescu, Hikaru Sasaki, gressive tumors that are clinically and genotypically similar David R. Macdonald, to glioblastomas. Conclusions: These data raise the possibility, for the Anat O. Stemmer-Rachamimov, first time, that therapeutic decisions at the time of diagnosis 2 David A. Ramsay, J. Gregory Cairncross, and might be tailored to particular genetic subtypes of anaplastic David N. Louis oligodendroglioma. Molecular Neuro-Oncology Laboratory, Department of Pathology and Neurosurgical Service, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School [Y. I., H. S., A. O. S-R., D. N. L.] and Department of INTRODUCTION Biostatistics, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts Malignant gliomas are the most common type of primary 02114 [R. A. B.], and Departments of Clinical Neurological Sciences, ϳ Oncology, and Pathology, University of Western Ontario and London brain tumor, with 12,000 new cases diagnosed each year in the Regional Cancer Centre, London, Ontario N6A 4L6, Canada United States (1). For nearly a century, malignant gliomas have [M. C. Z., D. R. M., D. A. R., J. G. C.] been classified on the basis of their histological appearance as astrocytomas (including glioblastomas), oligodendrogliomas, ependymomas, or mixed gliomas. For each type, surgical resec- ABSTRACT tion and radiation therapy have been the mainstays of treatment. Purpose: In a prior study of anaplastic oligodendrogli- Cytotoxic drugs have had a relatively minor therapeutic role omas treated with chemotherapy at diagnosis or at recur- because responses to chemotherapy generally have been infre- rence after radiotherapy, allelic loss of chromosome 1p cor- quent, brief, and unpredictable. -

Farewell to Oligoastrocytoma: in Situ Molecular Genetics Favor Classification As Either Oligodendroglioma Or Astrocytoma

Acta Neuropathol (2014) 128:551–559 DOI 10.1007/s00401-014-1326-7 ORIGinaL PAPER Farewell to oligoastrocytoma: in situ molecular genetics favor classification as either oligodendroglioma or astrocytoma Felix Sahm · David Reuss · Christian Koelsche · David Capper · Jens Schittenhelm · Stephanie Heim · David T. W. Jones · Stefan M. Pfister · Christel Herold‑Mende · Wolfgang Wick · Wolf Mueller · Christian Hartmann · Werner Paulus · Andreas von Deimling Received: 29 April 2014 / Revised: 23 July 2014 / Accepted: 23 July 2014 / Published online: 21 August 2014 © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2014 Abstract Astrocytoma and oligodendroglioma are histo- in different institutions employing histology, immunohisto- logically and genetically well-defined entities. The majority chemistry and in situ hybridization addressing surrogates of astrocytomas harbor concurrent TP53 and ATRX muta- for the molecular genetic markers IDH1R132H, TP53, tions, while most oligodendrogliomas carry the 1p/19q ATRX and 1p/19q loss. In all but one OA the combination co-deletion. Both entities share high frequencies of IDH of nuclear p53 accumulation and ATRX loss was mutually mutations. In contrast, oligoastrocytomas (OA) appear less exclusive with 1p/19q co-deletion. In 31/43 OA, only altera- clearly defined and, therefore, there is an ongoing debate tions typical for oligodendroglioma were observed, while in whether these tumors indeed constitute an entity or whether 11/43 OA, only indicators for mutations typical for astrocy- they represent a mixed bag containing both astrocytomas tomas were detected. A single case exhibited a distinct pat- and oligodendrogliomas. We investigated 43 OA diagnosed tern, nuclear expression of p53, ATRX loss, IDH1 mutation and partial 1p/19q loss. However, this was the only patient undergoing radiotherapy prior to surgery, possibly contrib- Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00401-014-1326-7) contains supplementary uting to the acquisition of this uncommon combination.