Community Killing in Chimpanzees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan Paniscus)

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan paniscus) Editors: Dr Jeroen Stevens Contact information: Royal Zoological Society of Antwerp – K. Astridplein 26 – B 2018 Antwerp, Belgium Email: [email protected] Name of TAG: Great Ape TAG TAG Chair: Dr. María Teresa Abelló Poveda – Barcelona Zoo [email protected] Edition: First edition - 2020 1 2 EAZA Best Practice Guidelines disclaimer Copyright (February 2020) by EAZA Executive Office, Amsterdam. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in hard copy, machine-readable or other forms without advance written permission from the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). Members of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) may copy this information for their own use as needed. The information contained in these EAZA Best Practice Guidelines has been obtained from numerous sources believed to be reliable. EAZA and the EAZA APE TAG make a diligent effort to provide a complete and accurate representation of the data in its reports, publications, and services. However, EAZA does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information. EAZA disclaims all liability for errors or omissions that may exist and shall not be liable for any incidental, consequential, or other damages (whether resulting from negligence or otherwise) including, without limitation, exemplary damages or lost profits arising out of or in connection with the use of this publication. Because the technical information provided in the EAZA Best Practice Guidelines can easily be misread or misinterpreted unless properly analysed, EAZA strongly recommends that users of this information consult with the editors in all matters related to data analysis and interpretation. -

Conflict and Cooperation in Wild Chimpanzees

ADVANCES IN THE STUDY OF BEHAVIOR VOL. 35 Conflict and Cooperation in Wild Chimpanzees MARTIN N. MULLER* and JOHN C. MITANIt *DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY BOSTON UNIVERSITY BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, 02215, USA tDEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN, 48109, USA 1. INTRODUCTION The twin themes of competition and cooperation have been the focus of many studies in animal behavior (Alcock, 2001; Dugatkin, 2004; Krebs and Davies, 1997). Competition receives prominent attention because it forms the basis for the unifying, organizing principle of biology. Darwin's (1859) theory of natural selection furnishes a powerful framework to understand the origin and maintenance of organic and behavioral diversity. Because the process of natural selection depends on reproductive competition, aggression, dominance, and competition for mates serve as important foci of ethological research. In contrast, cooperation in animals is less easily explained within a Darwinian framework. Why do animals cooperate and behave in ways that benefit others? Supplements to the theory of natural selection in the form of kin selection, reciprocal altruism, and mutualism provide mechanisms that transform the study of cooperative behavior in animals into a mode of inquiry compatible with our current understand- ing of the evolutionary process (Clutton-Brock, 2002; Hamilton, 1964; Trivers, 1971). If cooperation can be analyzed via natural selection operating on indivi- duals, a new way to conceptualize the process emerges. Instead of viewing cooperation as distinct from competition, it becomes productive to regard them together. Students of animal behavior have long recognized that an artificial dichotomy may exist insofar as animals frequently cooperate to compete with conspecifics. -

The Cognitive Animal Empirical and Theoretical Perspectives on Animal Cognition

This PDF includes a chapter from the following book: The Cognitive Animal Empirical and Theoretical Perspectives on Animal Cognition © 2002 Massachusetts Institute of Technology License Terms: Made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ OA Funding Provided By: The open access edition of this book was made possible by generous funding from Arcadia—a charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin. The title-level DOI for this work is: doi:10.7551/mitpress/1885.001.0001 Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/books/edited-volume/chapter-pdf/677498/9780262268028_c002400.pdf by guest on 25 September 2021 Chimpanzee Ai and Her Son Ayumu: An Episode of Education by Master- 25 Apprenticeship Tetsuro Matsuzawa I have been studying chimpanzee (Pan troglo- use has never before been found in nonhuman dytes) intelligence both in the laboratory and animals. Humans show strong hand preference in the wild (Matsuzawa 2001). Chimpanzees in on the individual level, and there is also a strong the wild use and manufacture a wide variety of right bias at the population level. The chimpan- tools, such as twigs to fish for termites or a pair zees of Bossou show a slight bias toward the of stones to crack open hard-shelled nuts. Re- right for hammering at the population level, with cent studies comparing di¤erent communities of about 67 percent of group members being right- chimpanzees have shown that each community handers. However, there is perfect correspon- develops its own unique set of cultural traditions. -

Bonobos (Pan Paniscus) Show an Attentional Bias Toward Conspecifics’ Emotions

Bonobos (Pan paniscus) show an attentional bias toward conspecifics’ emotions Mariska E. Kreta,1, Linda Jaasmab, Thomas Biondac, and Jasper G. Wijnend aInstitute of Psychology, Cognitive Psychology Unit, Leiden University, 2333 AK Leiden, The Netherlands; bLeiden Institute for Brain and Cognition, 2300 RC Leiden, The Netherlands; cApenheul Primate Park, 7313 HK Apeldoorn, The Netherlands; and dPsychology Department, University of Amsterdam, 1018 XA Amsterdam, The Netherlands Edited by Susan T. Fiske, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, and approved February 2, 2016 (received for review November 8, 2015) In social animals, the fast detection of group members’ emotional perspective, it is most adaptive to be able to quickly attend to rel- expressions promotes swift and adequate responses, which is cru- evant stimuli, whether those are threats in the environment or an cial for the maintenance of social bonds and ultimately for group affiliative signal from an individual who could provide support and survival. The dot-probe task is a well-established paradigm in psy- care (24, 25). chology, measuring emotional attention through reaction times. Most primates spend their lives in social groups. To prevent Humans tend to be biased toward emotional images, especially conflicts, they keep close track of others’ behaviors, emotions, and when the emotion is of a threatening nature. Bonobos have rich, social debts. For example, chimpanzees remember who groomed social emotional lives and are known for their soft and friendly char- whom for long periods of time (26). In the chimpanzee, but also in acter. In the present study, we investigated (i) whether bonobos, the rarely studied bonobo, grooming is a major social activity and similar to humans, have an attentional bias toward emotional scenes a means by which animals living in proximity may bond and re- ii compared with conspecifics showing a neutral expression, and ( ) inforce social structures. -

Lethal Aggression in Pan Is Better Explained by Adaptive Strategies Than Human Impacts

LETTER doi:10.1038/nature13727 Lethal aggression in Pan is better explained by adaptive strategies than human impacts Michael L. Wilson1,2, Christophe Boesch3, Barbara Fruth4,5, Takeshi Furuichi6, Ian C. Gilby7,8, Chie Hashimoto6, Catherine L. Hobaiter9, Gottfried Hohmann3, Noriko Itoh10, Kathelijne Koops11, Julia N. Lloyd12, Tetsuro Matsuzawa6,13, John C. Mitani14, Deus C. Mjungu15, David Morgan16, Martin N. Muller17, Roger Mundry18, Michio Nakamura10, Jill Pruetz19, Anne E. Pusey7, Julia Riedel3, Crickette Sanz20, Anne M. Schel21, Nicole Simmons12, Michel Waller22, David P. Watts23, Frances White22, Roman M. Wittig3, Klaus Zuberbu¨hler9,24 & Richard W. Wrangham25 Observations of chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and bonobos (Pan In contrast, the adaptive strategies hypothesis views killing as an paniscus) provide valuable comparative data for understanding the evolved tactic by which killers tend to increase their fitness through significance of conspecific killing. Two kinds of hypothesis have increased access to territory, food, mates or other benefits1–5,10–17.Kin been proposed. Lethal violence is sometimes concluded to be the selection18 and evolutionary game theory19 yield a set of specific predic- result of adaptive strategies, such that killers ultimately gain fit- tions for how benefits and costs should vary with the context, age, sex, ness benefits by increasing their access to resources such as food or and genetic relatedness of the attackers and targets. Lethal aggression mates1–5. Alternatively, it could be a non-adaptive result of human occurs within a diverse set of circumstances, but is expected to be most impacts, such as habitat change or food provisioning6–9. To discri- commonly committed by males; directed towards males; directed towards minate between these hypotheses we compiled information from non-kin, particularly members of other groups; and committed when 18 chimpanzee communities and 4 bonobo communities studied overwhelming numerical superiority reduces the costs of killing. -

Death of a Trapped Chimpanzee: Survival and Conservation of Great Apes in Unprotected Agricultural Areas of Uganda

African Primates 13: 47-56 (2019)/ 47 Case Study: Death of a Trapped Chimpanzee: Survival and Conservation of Great Apes in Unprotected Agricultural Areas of Uganda Marie Cibot1,2,3, Sarah Le Roux⁴, Jacqueline Rohen2, and Matthew R. McLennan1,2,5 1Department of Social Sciences, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, United Kingdom; 2Bulindi Chimpanzee and Community Project, Hoima, Uganda; 3Anicoon Vétérinaires, Ploemeur/ Larmor- Plage, France; 4Département de Pathologie Cellulaire et Tissulaire, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire d’Angers, Angers, France; 5Centre for Ecology and Conservation, University of Exeter, Cornwall, United Kingdom Abstract: Rural, human-dominated landscapes present substantial risks to chimpanzees and other primates. In western Uganda, some farmers guard against crop losses to wildlife by placing large steel leg-hold traps (‘mantraps’) near their agricultural fields. Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii) can step in these illegal devices, resulting in severe injury or death. Here, we report a case of trapping and subsequent death of a wild chimpanzee from the Bulindi community (Hoima District). The elderly female chimpanzee died 13 days after being injured by a mantrap. Her injury could have contributed to the cause of death by impacting her balance in low trees above a stream; her body was subsequently found in the water. Behavioural observations prior to death and evidence from physical inspection of her injured hand suggest she may have otherwise recovered from her -

Chimpanzee Referents and the Emergence of Human Hunting Travis Rayne Pickering*,1,2 and Manuel Domínguez-Rodrigo3

The Open Anthropology Journal, 2010, 3, 107-113 107 Open Access Chimpanzee Referents and the Emergence of Human Hunting Travis Rayne Pickering*,1,2 and Manuel Domínguez-Rodrigo3 1Department of Anthropology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1180 Observatory Drive, 5240 Social Building, Madison, Wisconsin, 53706, USA; 2Institute for Human Evolution, University of the Witwatersrand, Private Bag 3, WITS 2050, Johannesburg, South Africa; 3Department of Prehistory, Complutense University, 28040, Madrid, Spain Abstract: The use of referent taxa, and especially chimpanzee referents, in modeling human evolution has been harshly criticized. No doubt, chimpanzee data are often misused in models of early hominid behavior. But, those misuses are ex- amples of careless, formal analogizing. In contrast, it is equally possible to create non-trivial chimpanzee analogies. These analogies can, in turn, be linked together to construct credible models of human evolution, from which emanate hypothe- ses that are testable using paleoanthropological data. Unique among potential referents, chimpanzees are very closely re- lated to early hominids and some populations reside in ecological contexts that are comparable to those of our African an- cestors. It is these two variables that form the core of evolutionary behavioral ecology. We exploit chimpanzee and early hominid continuities and employ non-trivial analogies to provide a model of basal hominid hunting. The model is testable and the topic is worthy because hunting and meat-eating are argued by some to be the basis of human sociality. Keywords: Uniformitarianism, modeling, human evolution, predation, meat-eating. INTRODUCTION mandible and on the ventral surface of a rib implies filleting of fully fleshed limbs and the removal of the tongue and up- Human hunting is unique. -

©TH @Reem W©Rea Edife©Eefff

©TH @REEm w©REa EDife©EEffF Reading/ Writing (3-week assignment) 1. Complete the Performance tack on Can Animals learn or use language? (Week 1} a. Read and highlight important fact b. Answer the questions on the bottom of each page that has a question c. Complete the multiple choice and essay question on pages 29-30 2. On page 31- write down your claim (Can animals team or use lartguage?} /Wbe* 2/ a. Come up with 3 reasons and facts on why animals can or cannot learn or use language b. Write a counterclaim (what other people believe) and with a fact of why they believe that c. Write a conclusion. In the conclusion you need summarize your reasons on why you believe animals can or cannot use or leam language 3. Before Writing the essay: Do some practice skills. a. Complete the Organization Challenge for an Introduction, Body paragraphs 1-3, and conclusion. Review the complete essay to see how you did b. Reviewthe Essay Exampleto see howthe facts are put together 4. Writing your essay: use the graphic organizer to begin writing your essay with the facts you have gathered and then transfer it on to binder paper (you may type it if you would like). /Week 3/ a. Make sure you cite (for example: /n soune I /.rstates.„} b. Use quotation marks when copying a direct quote from the sources c. Each paragraph should have at least4 complete and detailed sentences Studies Weekly (One per Week) Historv/ Social Science Week ffl (People of Phoenicia) and Week #15 (More African Kingdoms) Read, highlight/ underline important facts. -

Between the Gorilla and the Chimpanzee: a History of Debate Concerning the Existence of the Kooloo-Kamba Or Gorilla-Like Chimpanzee

"J. Ethnobiol. 4(1): 1-13 May 1984 BETWEEN THE GORILLA AND THE CHIMPANZEE: A HISTORY OF DEBATE CONCERNING THE EXISTENCE OF THE KOOLOO-KAMBA OR GORILLA-LIKE CHIMPANZEE BRIAN T. SHEA Department ofAnthropology and Cell Biology & Anatomy Northwestern University 2006 Sheridan Road Evanston, IL 60201 ABSTRACT.-The taxonomic scheme proposed in 1934 by Ernst Schwarz for the subspec ific classification of common chimpanzees (P(J.n troglody tes) has been accepted by the majority of subsequent primatologists. A notable exception to this general trend is that the late W. C. O. Hill continued and revived a long history of controversial debate over the existence of a rare gorilla-like chimpanzee subspecies known as the "kooloo-kamba." The history of the enigmatic kooloo-kamba is reviewed here, from its early discovery and des cription by DuChaillu, through the morphological investigations of Keith, Schwarz, Merfield, and others, and finally to the more recent claims of Hill. Almost all claims supporting the existence of the kooloo-kamba have invoked indigenous labels and folk taxonomies as t'yJdence. The prolonged debate provides insights into the relationships between folk taxonomies and our own classifications. Confusion, vanatlon, and me u~~ 0"/ ,i'i'&"J.~\"ru".a..tc.t.!'" or hybrid categories in both Western and indigenous classifications probably reflects a salient biologic fact-gorillas and chimpanzees are very closely related animals with patterns of morphological development which coincide and overlap. INTRODUCTION During the late 1800s and early 1900s, a large number of chimpanzee and gorilla species were described by various workers, often on the basis of a particular variation of facial coloring, hair distribution, or cranial shape. -

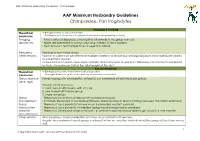

Minimum Husbandry Guidelines for Chimpanzee, Pan Troglodytes

AAP Minimum Husbandry Guidelines: Chimpanzee AAP Minimum Husbandry Guidelines Chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes Foraging & Feeding Theoretical → Biological need to vary in food items. conclusion → Ethological need to perform foraging behaviour (searching/working for food). Foraging - Food is offered dispersed, ensuring that all animals in the group can eat. opportunity - Meals are presented in various ways (e.g. hidden, in food puzzles). - Fresh browse is fed multiple times a week if available. Frequency Feeding at least twice a day. Other remarks Food and water must be offered at multiple locations to ensure low-ranking individuals have adequate access to water/food sources. Cultivated fruits contain more sugars and less fibre compared to wild fruits. Therefore, not too much fruit should be fed, 5 to maximum 25% of the total weight of the diet. Social interaction Theoretical → Ethological need for social contact with conspecifics. conclusion → Managerial need for gradual introductions of unfamiliar conspecifics. Group structure Social housing with conspecifics: at least 2, but preferably ≥4 individuals per group. (sexe, age) Possible social structures: 1. multi-male/multi-female, with ♂♂ < ♀♀. 2. one male/multi-female group. 3. single sex group. Group - There must be at least 2 indoor and 1 outdoor enclosure. management - If animals are locked in the inside enclosures, there must be at least 2 hatches between the indoor enclosures. Social - There must be a possibility to have visual & protected contact (animals). introductions - There must be a possibility to interfere during the physical phase (caretakers). (hatches, - There must be escape routes available, i.e. animals should always be able to get away in a safe manner. -

The Ecological Role of the Bonobo: Seed Dispersal Service in Congo Forests

The ecological role of the Bonobo : seed dispersal service in Congo forests David Beaune To cite this version: David Beaune. The ecological role of the Bonobo : seed dispersal service in Congo forests. Agricultural sciences. Université de Bourgogne, 2012. English. NNT : 2012DIJOS096. tel-00932505 HAL Id: tel-00932505 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00932505 Submitted on 17 Jan 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITE DE BOURGOGNE UFR Sciences de la Vie, de la Terre et de l'Environnement THÈSE Pour obtenir le grade de Docteur de l’Université de Bourgogne Discipline : Sciences Vie par David Beaune le 28 novembre 2012 The Ecological Role of the Bonobo Seed dispersal service in Congo forests Directeurs de thèse Pr Loïc Bollache, uB Pr François Bretagnolle, uB Dr Barbara Fruth, MPI Jury Bollache, Loïc Prof. Université de Bourgogne Directeur Bretagnolle, François Prof. Université de Bourgogne Directeur Hart, John Dr. Lukuru Research Fundation Rapporteur Krief, Sabrina Dr. MNHN Paris Examinateur McKey, Doyle Prof. Université de Montpellier Rapporteur © Aux jardiniers des forêts. Puissent-ils encore vivre… tout simplement 1 Remerciements Financeurs : Le projet « Rôle écologique des bonobos » a bénéficié de diverses sources de financements : . -

Dispersal and Integration in Female Chimpanzees by Kara Kristina Walker Department of Evolutionary Anthropology Duke University

Dispersal and Integration in Female Chimpanzees by Kara Kristina Walker Department of Evolutionary Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Anne Pusey, Supervisor ___________________________ Brian Hare ___________________________ Susan Alberts ___________________________ Christine Drea Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Evolutionary Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 ABSTRACT Dispersal and Integration in Female Chimpanzees by Kara Kristina Walker Department of Evolutionary Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Anne Pusey, Supervisor ___________________________ Brian Hare ___________________________ Susan Alberts ___________________________ Christine Drea An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Evolutionary Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 Copyright by Kara Kristina Walker 2015 Abstract In chimpanzees, most females disperse from the community in which they were born to reproduce in a new community, thereby eliminating the risk of inbreeding with close kin. However, across sites, some females breed in their natal community, raising questions about the flexibility of dispersal, the costs and benefits of different strategies and the mitigation of costs associated with dispersal and integration. In this dissertation I address these questions by combining long-term behavioral data and recent field observations on maturing and young adult females in Gombe National Park with an experimental manipulation of relationship formation in captive apes in the Congo. To assess the risk of inbreeding for females who do and do not disperse, 129 chimpanzees were genotyped and relatedness between each dyad was calculated.