Arxiv:2012.00080V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 24 Dec 2020 [email protected] Ie Ogeog Eprlbsln Fobservations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planetary Phase Variations of the 55 Cancri System

The Astrophysical Journal, 740:61 (7pp), 2011 October 20 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/740/2/61 C 2011. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. PLANETARY PHASE VARIATIONS OF THE 55 CANCRI SYSTEM Stephen R. Kane1, Dawn M. Gelino1, David R. Ciardi1, Diana Dragomir1,2, and Kaspar von Braun1 1 NASA Exoplanet Science Institute, Caltech, MS 100-22, 770 South Wilson Avenue, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC V6T1Z1, Canada Received 2011 May 6; accepted 2011 July 21; published 2011 September 29 ABSTRACT Characterization of the composition, surface properties, and atmospheric conditions of exoplanets is a rapidly progressing field as the data to study such aspects become more accessible. Bright targets, such as the multi-planet 55 Cancri system, allow an opportunity to achieve high signal-to-noise for the detection of photometric phase variations to constrain the planetary albedos. The recent discovery that innermost planet, 55 Cancri e, transits the host star introduces new prospects for studying this system. Here we calculate photometric phase curves at optical wavelengths for the system with varying assumptions for the surface and atmospheric properties of 55 Cancri e. We show that the large differences in geometric albedo allows one to distinguish between various surface models, that the scattering phase function cannot be constrained with foreseeable data, and that planet b will contribute significantly to the phase variation, depending upon the surface of planet e. We discuss detection limits and how these models may be used with future instrumentation to further characterize these planets and distinguish between various assumptions regarding surface conditions. -

Interior Dynamics of Super-Earth 55 Cancri E Constrained by General Circulation Models

Geophysical Research Abstracts Vol. 21, EGU2019-4167, 2019 EGU General Assembly 2019 © Author(s) 2019. CC Attribution 4.0 license. Interior dynamics of super-Earth 55 Cancri e constrained by general circulation models Tobias Meier (1), Dan J. Bower (1), Tim Lichtenberg (2), and Mark Hammond (2) (1) Center for Space and Habitability, Universität Bern , Bern, Switzerland , (2) Department of Physics, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom Close-in and tidally-locked super-Earths feature a day-side that always faces the host star and are thus subject to intense insolation. The thermal phase curve of 55 Cancri e, one of the best studied super-Earths, reveals a hotspot shift (offset of the maximum temperature from the substellar point) and a large day-night temperature contrast. Recent general circulation models (GCMs) aiming to explain these observations determine the spatial variability of the surface temperature of 55 Cnc e for different atmospheric masses and compositions. Here, we use constraints from the GCMs to infer the planet’s interior dynamics using a numerical geodynamic model of mantle flow. The geodynamic model is devised to be relatively simple due to uncertainties in the interior composition and structure of 55 Cnc e (and super-Earths in general), which preclude a detailed treatment of thermophysical parameters or rheology. We focus on several end-member models inspired by the GCM results to map the variety of interior regimes relevant to understand the present-state and evolution of 55 Cnc e. In particular, we investigate differences in heat transport and convective style between the day- and night-sides, and find that the thermal structure close to the surface and core-mantle boundary exhibits the largest deviations. -

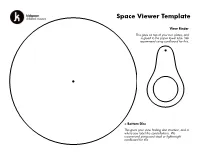

Space Viewer Template

Space Viewer Template View Finder This goes on top of your two plates, and is glued to the paper towel tube. We recommend using cardboard for this. < Bottom Disc This gives your view finding disc structure, and is where you label the constellations. We recommend using card stock or lightweight cardboard for this. Constellation Plate > This disc is home to your constellations, and gets glued to the larger disc. We recommend using paper for this, so the holes are easier to punch. Use the punch guides on the next page to punch holes and add labels to your viewer. Orion Cancer Look for the middle star of Orions When you look at this constellation, look sword, that is an area of brighter nearby for 55 Cancri a star that has light, it’s actually a nebula! The five exoplanets orbiting it. One of those Orion Nebula is a gigantic cloud of plants (55 Cancri e) is a super hot dust and gas, where new stars are planet entirely covered in an ocean of being created. lava! Cygnus Andromeda This constellation is home to the This constellation is very close to the Kepler-186 system, including the Andromeda Galaxy (an enormous planet Kepler-186f. Seen by collection of gas, dust, and billions of NASA's Kepler Space Telescope, stars and solar systems). This spiral this is the first Earth-sized planet galaxy is so bright, you can spot it with discovered that is in"habitable the naked eye! zone" of its star. Ursa Minor Cassiopeia Ursa Minor has two stars known While gazing at Cassiopeia look for with exoplanets orbiting them - the“Pacman Nebula” (It’s official name both are gas giants, that are much is NGC 281). -

A Case for an Atmosphere on Super-Earth 55 Cancri E

The Astronomical Journal, 154:232 (8pp), 2017 December https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-3881/aa9278 © 2017. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. A Case for an Atmosphere on Super-Earth 55 Cancri e Isabel Angelo1,2 and Renyu Hu1,3 1 Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, CA 91109, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Astronomy, University of California, Campbell Hall, #501, Berkeley CA, 94720, USA 3 Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA Received 2017 August 2; revised 2017 October 6; accepted 2017 October 8; published 2017 November 16 Abstract One of the primary questions when characterizing Earth-sized and super-Earth-sized exoplanets is whether they have a substantial atmosphere like Earth and Venus or a bare-rock surface like Mercury. Phase curves of the planets in thermal emission provide clues to this question, because a substantial atmosphere would transport heat more efficiently than a bare-rock surface. Analyzing phase-curve photometric data around secondary eclipses has previously been used to study energy transport in the atmospheres of hot Jupiters. Here we use phase curve, Spitzer time-series photometry to study the thermal emission properties of the super-Earth exoplanet 55 Cancri e. We utilize a semianalytical framework to fit a physical model to the infrared photometric data at 4.5 μm. The model uses parameters of planetary properties including Bond albedo, heat redistribution efficiency (i.e., ratio between radiative timescale and advective timescale of the atmosphere), and the atmospheric greenhouse factor. -

Abstracts of Extreme Solar Systems 4 (Reykjavik, Iceland)

Abstracts of Extreme Solar Systems 4 (Reykjavik, Iceland) American Astronomical Society August, 2019 100 — New Discoveries scope (JWST), as well as other large ground-based and space-based telescopes coming online in the next 100.01 — Review of TESS’s First Year Survey and two decades. Future Plans The status of the TESS mission as it completes its first year of survey operations in July 2019 will bere- George Ricker1 viewed. The opportunities enabled by TESS’s unique 1 Kavli Institute, MIT (Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States) lunar-resonant orbit for an extended mission lasting more than a decade will also be presented. Successfully launched in April 2018, NASA’s Tran- siting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) is well on its way to discovering thousands of exoplanets in orbit 100.02 — The Gemini Planet Imager Exoplanet Sur- around the brightest stars in the sky. During its ini- vey: Giant Planet and Brown Dwarf Demographics tial two-year survey mission, TESS will monitor more from 10-100 AU than 200,000 bright stars in the solar neighborhood at Eric Nielsen1; Robert De Rosa1; Bruce Macintosh1; a two minute cadence for drops in brightness caused Jason Wang2; Jean-Baptiste Ruffio1; Eugene Chiang3; by planetary transits. This first-ever spaceborne all- Mark Marley4; Didier Saumon5; Dmitry Savransky6; sky transit survey is identifying planets ranging in Daniel Fabrycky7; Quinn Konopacky8; Jennifer size from Earth-sized to gas giants, orbiting a wide Patience9; Vanessa Bailey10 variety of host stars, from cool M dwarfs to hot O/B 1 KIPAC, Stanford University (Stanford, California, United States) giants. 2 Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology TESS stars are typically 30–100 times brighter than (Pasadena, California, United States) those surveyed by the Kepler satellite; thus, TESS 3 Astronomy, California Institute of Technology (Pasadena, Califor- planets are proving far easier to characterize with nia, United States) follow-up observations than those from prior mis- 4 Astronomy, U.C. -

How to Detect Exoplanets Exoplanets: an Exoplanet Or Extrasolar Planet Is a Planet Outside the Solar System

Exoplanets Matthew Sparks, Sobya Shaikh, Joseph Bayley, Nafiseh Essmaeilzadeh How to detect exoplanets Exoplanets: An exoplanet or extrasolar planet is a planet outside the Solar System. Transit Method: When a planet crosses in front of its star as viewed by an observer, the event is called a transit. Transits by terrestrial planets produce a small change in a star's brightness of about 1/10,000 (100 parts per million, ppm), lasting for 2 to 16 hours. This change must be absolutely periodic if it is caused by a planet. In addition, all transits produced by the same planet must be of the same change in brightness and last the same amount of time, thus providing a highly repeatable signal and robust detection method. Astrometry: Astrometry is the area of study that focuses on precise measurements of the positions and movements of stars and other celestial bodies, as well as explaining these movements. In this method, the gravitational pull of a planet causes a star to change its orbit over time. Careful analysis of the changes in a star's orbit can provide an indication that there exists a massive exoplanet in orbit around the star. The astrometry technique has benefits over other exoplanet search techniques because it can locate planets that orbit far out from the star Radial Velocity method: The radial velocity method to detect exoplanet is based on the detection of variations in the velocity of the central star, due to the changing direction of the gravitational pull from an (unseen) exoplanet as it orbits the star. -

Bayesian Analysis of Interiors of HD 219134B, Kepler-10B, Kepler-93B, Corot-7B, 55 Cnc E, and HD 97658B Using Stellar Abundance

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. output c ESO 2016 September 13, 2016 Bayesian analysis of interiors of HD 219134b, Kepler-10b, Kepler-93b, CoRoT-7b, 55 Cnc e, and HD 97658b using stellar abundance proxies Caroline Dorn1, Natalie R. Hinkel2, and Julia Venturini1 1 Physics Institute, University of Bern, Sidlerstrasse 5, CH-3012, Bern, Switzerland e-mail: [email protected] 2 School of Earth & Space Exploration, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287, USA September 13, 2016 ABSTRACT Aims. Using a generalized Bayesian inference method, we aim to explore the possible interior structures of six selected exoplanets for which planetary mass and radius measurements are available in addition to stellar host abundances: HD 219134b, Kepler-10b, Kepler- 93b, CoRoT-7b, 55 Cnc e, and HD 97658b. We aim to investigate the importance of stellar abundance proxies for the planetary bulk composition (namely Fe/Si and Mg/Si) on prediction of planetary interiors. Methods. We performed a full probabilistic Bayesian inference analysis to formally account for observational and model uncertainties while obtaining confidence regions of structural and compositional parameters of core, mantle, ice layer, ocean, and atmosphere. We determined how sensitive our parameter predictions depend on (1) different estimates of bulk abundance constraints and (2) different correlations of bulk abundances between planet and host star. Results. The possible interior structures and correlations between structural parameters differ depending on data and data uncertainty. The strongest correlation is generally found between size of rocky interior and water mass fraction. Given the data, possible water mass fractions are high, even for most potentially rocky planets (HD 219134b, Kepler-93b, CoRoT-7b, and 55 Cnc e with estimates up to 35 %, depending on the planet). -

Zone Eight-Earth-Mass Planet K2-18 B

LETTERS https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-019-0878-9 Water vapour in the atmosphere of the habitable- zone eight-Earth-mass planet K2-18 b Angelos Tsiaras *, Ingo P. Waldmann *, Giovanna Tinetti , Jonathan Tennyson and Sergey N. Yurchenko In the past decade, observations from space and the ground planet within the star’s habitable zone (~0.12–0.25 au) (ref. 20), with have found water to be the most abundant molecular species, effective temperature between 200 K and 320 K, depending on the after hydrogen, in the atmospheres of hot, gaseous extrasolar albedo and the emissivity of its surface and/or its atmosphere. This planets1–5. Being the main molecular carrier of oxygen, water crude estimate accounts for neither possible tidal energy sources21 is a tracer of the origin and the evolution mechanisms of plan- nor atmospheric heat redistribution11,13, which might be relevant for ets. For temperate, terrestrial planets, the presence of water this planet. Measurements of the mass and the radius of K2-18 b 22 is of great importance as an indicator of habitable conditions. (planetary mass Mp = 7.96 ± 1.91 Earth masses (M⊕) (ref. ), plan- 19 Being small and relatively cold, these planets and their atmo- etary radius Rp = 2.279 ± 0.0026 R⊕ (ref. )) yield a bulk density of spheres are the most challenging to observe, and therefore no 3.3 ± 1.2 g cm−1 (ref. 22), suggesting either a silicate planet with an 6 atmospheric spectral signatures have so far been detected . extended atmosphere or an interior composition with a water (H2O) Super-Earths—planets lighter than ten Earth masses—around mass fraction lower than 50% (refs. -

The Hunt for Sara Seager Astronomers Are fi Nding and Studying Worlds Just a Little Larger Than Ours

Closing in on Life-Bearing Planets Super-EarthsThe Hunt for sara seager Astronomers are fi nding and studying worlds just a little larger than ours. For thousands of years people What’s a Super-Earth? Super-Earths are unoffi cially defi ned as planets with have wondered if we are alone. masses between about 1 and 10 Earth masses. The term is largely reserved for planets that are rocky in nature rather Modern astronomers pose the than for planets that have icy interiors or signifi cant gas envelopes. Astronomers refer to the latter as exo-Nep- question in a slightly diff erent tunes. Because super-Earths and exo-Neptunes may be continuous and have an overlapping mass range, they are way, a way that can be answered often discussed together. Super-Earths are fascinating because they have no quantitatively, in stages, in the solar-system counterparts, because they represent our nearest-term hope for fi nding habitable planets, and near future: Are there planets because they should display a huge diversity of properties. The wide and almost continuous spread of giant exo- like Earth? Are they common? planet masses and orbits illustrates the random nature of planet formation and migration; this trend surely extends Do any of them have signs of to super-Earths as well. Indeed, even though about two dozen are known so far, their range of masses and orbits life? The hunt for life-sustain- supports this notion. Current detection methods are biased toward fi nding close-in super-Earths, so there’s ing exoplanets is accelerating as undoubtedly a huge population waiting to be discovered. -

Tsiaras Et Al. 2016

The Astrophysical Journal, 820:99 (13pp), 2016 April 1 doi:10.3847/0004-637X/820/2/99 © 2016. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. DETECTION OF AN ATMOSPHERE AROUND THE SUPER-EARTH 55 CANCRI E A. Tsiaras1, M. Rocchetto1, I. P. Waldmann1, O. Venot2, R. Varley1, G. Morello1, M. Damiano1,3, G. Tinetti1, E. J. Barton1, S. N. Yurchenko1, and J. Tennyson1 1 Department of Physics & Astronomy, University College London, Gower Street, WC1E6BT London, UK; [email protected] 2 Instituut voor Sterrenkunde, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Celestijnenlaan 200D, B-3001 Leuven, Belgium 3 INAF–Osservatorio Astronomico di Palermo, Piazza del Parlamento 1, I-90134 Palermo, Italy Received 2015 November 27; accepted 2016 February 5; published 2016 March 24 ABSTRACT We report the analysis of two new spectroscopic observations in the near-infrared of the super-Earth 55 Cancri e, obtained with the WFC3 camera on board the Hubble Space Telescope. 55 Cancri e orbits so close to its parent star that temperatures much higher than 2000 K are expected on its surface. Given the brightness of 55 Cancri, the observations were obtained in scanning mode, adopting a very long scanning length and a very high scanning speed. We use our specialized pipeline to take into account systematics introduced by these observational parameters when coupled with the geometrical distortions of the instrument. We measure the transit depth per wavelength channel with an average relative uncertainty of 22 ppm per visit and find modulations that depart from a straight line model with a 6σ confidence level. These results suggest that 55 Cancri e is surrounded by an atmosphere, which is probably hydrogen-rich. -

1952 (Created: Wednesday, August 25, 2021 at 11:00:43 AM Eastern Standard Time) - Overview

JWST Proposal 1952 (Created: Wednesday, August 25, 2021 at 11:00:43 AM Eastern Standard Time) - Overview 1952 - Determining the Atmospheric Composition of the Super-Earth 55 Cancri e Cycle: 1, Proposal Category: GO INVESTIGATORS Name Institution E-Mail Dr. Renyu Hu (PI) Jet Propulsion Laboratory [email protected] Dr. Alexis Brandeker (CoI) (ESA Member) Stockholm University [email protected] Dr. Mario Damiano (CoI) Jet Propulsion Laboratory [email protected] Prof. Brice-Olivier Demory (CoI) (ESA Member) University of Bern [email protected] Dr. Diana Dragomir (CoI) University of New Mexico [email protected] Dr. Yuichi Ito (CoI) (ESA Member) University College London (UCL) [email protected] Dr. Heather A. Knutson (CoI) California Institute of Technology [email protected] Dr. Yamila Miguel (CoI) (ESA Member) Universiteit Leiden [email protected] Michael Zhang (CoI) California Institute of Technology [email protected] OBSERVATIONS Folder Observation Label Observing Template Science Target Observation Folder 1 NIRCAM F444W Eclip NIRCam Grism Time Series (1) -RHO01-CNC se 2 MIRI LRS Eclipse MIRI Low Resolution Spectroscopy (1) -RHO01-CNC ABSTRACT One of the primary inquiries of astronomy is to determine for small exoplanets (1) whether they have an atmosphere, and (2) what their atmospheres are made of. To date, we have answered the first question for only one planet that is rocky in composition and lacking an H2-dominated atmosphere (i.e., a super-Earth): 55 Cancri e. Here we propose to use JWST's spectral capabilities in the mid-infrared to answer the second question for this planet. -

First Detection of Super-Earth Atmosphere 16 February 2016

First detection of super-earth atmosphere 16 February 2016 Using observations made with the Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3) on board the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope, the scientists were able to analyse the atmosphere of this exoplanet. This makes it the first detection of gases in the atmosphere of a super-Earth. The results allowed the team to examine the atmosphere of 55 Cancri e in detail and revealed the presence of hydrogen and helium, but no water vapour. These results were only made possible by exploiting a newly- developed processing technique. "This is a very exciting result because it's the first time that we have been able to find the spectral fingerprints that show the gases present in the This artist's impression shows the super-Earth 55 Cancri atmosphere of a super-Earth," explains Angelos e in front of its parent star. Using observations made Tsiaras, a PhD student at UCL, who developed the with the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope and new analysis technique along with his colleagues Ingo analytic software scientists were able to analyse the Waldmann and Marco Rocchetto. "The composition of its atmosphere. It was the first time this observations of 55 Cancri e's atmosphere suggest was possible for a super-Earth.55 Cancri e is about 40 that the planet has managed to cling on to a light-years away and orbits a star slightly smaller, cooler significant amount of hydrogen and helium from the and less bright than our Sun. As the planet is so close to nebula from which it originally formed." its parent star, one year lasts only 18 hours and temperatures on the surface are thought to reach around 2000 degrees Celsius.