Arxiv:1210.2720V1 [Astro-Ph.EP] 9 Oct 2012 Xli H Bevdrdu.Cneunl,Amassive a Barely Consequently, Only ( Could Radius

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radio and IR Interferometry of Sio Maser Stars

Cosmic Masers - from OH to H0 Proceedings IAU Symposium No. 287, 2012 c International Astronomical Union 2012 R.S. Booth, E.M.L. Humphreys & W.H.T. Vlemmings, eds. doi:10.1017/S1743921312006989 Radio and IR interferometry of SiO maser stars Markus Wittkowski1, David A. Boboltz2,MalcolmD.Gray3, Elizabeth M. L. Humphreys1 Iva Karovicova4, and Michael Scholz5,6 1 ESO, Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 2, 85748 Garching bei M¨unchen, Germany 2 US Naval Observatory, 3450 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20392-5420, USA 3 Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics, Alan Turing Building, University of Manchester, Manchester M13 9PL, UK 4 Max-Planck-Institut f¨ur Astronomie, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany 5 Zentrum f¨ur Astronomie der Universit¨at Heidelberg (ZAH), Institut f¨ur Theoretische Astrophysik, Albert-Ueberle-Str. 2, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany 6 Sydney Institute for Astronomy, School of Physics, University of Sydney, Sydney NSW 2006, Australia Abstract. Radio and infrared interferometry of SiO maser stars provide complementary infor- mation on the atmosphere and circumstellar environment at comparable spatial resolution. Here, we present the latest results on the atmospheric structure and the dust condensation region of AGB stars based on our recent infrared spectro-interferometric observations, which represent the environment of SiO masers. We discuss, as an example, new results from simultaneous VLTI and VLBA observations of the Mira variable AGB star R Cnc, including VLTI near- and mid- infrared interferometry, as well as VLBA observations of the SiO maser emission toward this source. We present preliminary results from a monitoring campaign of high-frequency SiO maser emission toward evolved stars obtained with the APEX telescope, which also serves as a pre- cursor of ALMA images of the SiO emitting region. -

Lurking in the Shadows: Wide-Separation Gas Giants As Tracers of Planet Formation

Lurking in the Shadows: Wide-Separation Gas Giants as Tracers of Planet Formation Thesis by Marta Levesque Bryan In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Pasadena, California 2018 Defended May 1, 2018 ii © 2018 Marta Levesque Bryan ORCID: [0000-0002-6076-5967] All rights reserved iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost I would like to thank Heather Knutson, who I had the great privilege of working with as my thesis advisor. Her encouragement, guidance, and perspective helped me navigate many a challenging problem, and my conversations with her were a consistent source of positivity and learning throughout my time at Caltech. I leave graduate school a better scientist and person for having her as a role model. Heather fostered a wonderfully positive and supportive environment for her students, giving us the space to explore and grow - I could not have asked for a better advisor or research experience. I would also like to thank Konstantin Batygin for enthusiastic and illuminating discussions that always left me more excited to explore the result at hand. Thank you as well to Dimitri Mawet for providing both expertise and contagious optimism for some of my latest direct imaging endeavors. Thank you to the rest of my thesis committee, namely Geoff Blake, Evan Kirby, and Chuck Steidel for their support, helpful conversations, and insightful questions. I am grateful to have had the opportunity to collaborate with Brendan Bowler. His talk at Caltech my second year of graduate school introduced me to an unexpected population of massive wide-separation planetary-mass companions, and lead to a long-running collaboration from which several of my thesis projects were born. -

Evidence for Very Extended Gaseous Layers Around O-Rich Mira Variables and M Giants B

The Astrophysical Journal, 579:446–454, 2002 November 1 # 2002. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. EVIDENCE FOR VERY EXTENDED GASEOUS LAYERS AROUND O-RICH MIRA VARIABLES AND M GIANTS B. Mennesson,1 G. Perrin,2 G. Chagnon,2 V. Coude du Foresto,2 S. Ridgway,3 A. Merand,2 P. Salome,2 P. Borde,2 W. Cotton,4 S. Morel,5 P. Kervella,5 W. Traub,6 and M. Lacasse6 Received 2002 March 15; accepted 2002 July 3 ABSTRACT Nine bright O-rich Mira stars and five semiregular variable cool M giants have been observed with the Infrared and Optical Telescope Array (IOTA) interferometer in both K0 (2.15 lm) and L0 (3.8 lm) broad- band filters, in most cases at very close variability phases. All of the sample Mira stars and four of the semire- gular M giants show strong increases, from ’20% to ’100%, in measured uniform-disk (UD) diameters between the K0 and L0 bands. (A selection of hotter M stars does not show such a large increase.) There is no evidence that K0 and L0 broadband visibility measurements should be dominated by strong molecular bands, and cool expanding dust shells already detected around some of these objects are also found to be poor candi- dates for producing these large apparent diameter increases. Therefore, we propose that this must be a con- tinuum or pseudocontinuum opacity effect. Such an apparent enlargement can be reproduced using a simple two-component model consisting of a warm (1500–2000 K), extended (up to ’3 stellar radii), optically thin ( ’ 0:5) layer located above the classical photosphere. -

Planetary Phase Variations of the 55 Cancri System

The Astrophysical Journal, 740:61 (7pp), 2011 October 20 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/740/2/61 C 2011. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. PLANETARY PHASE VARIATIONS OF THE 55 CANCRI SYSTEM Stephen R. Kane1, Dawn M. Gelino1, David R. Ciardi1, Diana Dragomir1,2, and Kaspar von Braun1 1 NASA Exoplanet Science Institute, Caltech, MS 100-22, 770 South Wilson Avenue, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC V6T1Z1, Canada Received 2011 May 6; accepted 2011 July 21; published 2011 September 29 ABSTRACT Characterization of the composition, surface properties, and atmospheric conditions of exoplanets is a rapidly progressing field as the data to study such aspects become more accessible. Bright targets, such as the multi-planet 55 Cancri system, allow an opportunity to achieve high signal-to-noise for the detection of photometric phase variations to constrain the planetary albedos. The recent discovery that innermost planet, 55 Cancri e, transits the host star introduces new prospects for studying this system. Here we calculate photometric phase curves at optical wavelengths for the system with varying assumptions for the surface and atmospheric properties of 55 Cancri e. We show that the large differences in geometric albedo allows one to distinguish between various surface models, that the scattering phase function cannot be constrained with foreseeable data, and that planet b will contribute significantly to the phase variation, depending upon the surface of planet e. We discuss detection limits and how these models may be used with future instrumentation to further characterize these planets and distinguish between various assumptions regarding surface conditions. -

Interior Dynamics of Super-Earth 55 Cancri E Constrained by General Circulation Models

Geophysical Research Abstracts Vol. 21, EGU2019-4167, 2019 EGU General Assembly 2019 © Author(s) 2019. CC Attribution 4.0 license. Interior dynamics of super-Earth 55 Cancri e constrained by general circulation models Tobias Meier (1), Dan J. Bower (1), Tim Lichtenberg (2), and Mark Hammond (2) (1) Center for Space and Habitability, Universität Bern , Bern, Switzerland , (2) Department of Physics, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom Close-in and tidally-locked super-Earths feature a day-side that always faces the host star and are thus subject to intense insolation. The thermal phase curve of 55 Cancri e, one of the best studied super-Earths, reveals a hotspot shift (offset of the maximum temperature from the substellar point) and a large day-night temperature contrast. Recent general circulation models (GCMs) aiming to explain these observations determine the spatial variability of the surface temperature of 55 Cnc e for different atmospheric masses and compositions. Here, we use constraints from the GCMs to infer the planet’s interior dynamics using a numerical geodynamic model of mantle flow. The geodynamic model is devised to be relatively simple due to uncertainties in the interior composition and structure of 55 Cnc e (and super-Earths in general), which preclude a detailed treatment of thermophysical parameters or rheology. We focus on several end-member models inspired by the GCM results to map the variety of interior regimes relevant to understand the present-state and evolution of 55 Cnc e. In particular, we investigate differences in heat transport and convective style between the day- and night-sides, and find that the thermal structure close to the surface and core-mantle boundary exhibits the largest deviations. -

Occurrence and Core-Envelope Structure of 1–4× Earth-Size Planets Around Sun-Like Stars

Occurrence and core-envelope structure of 1–4× SPECIAL FEATURE Earth-size planets around Sun-like stars Geoffrey W. Marcya,1, Lauren M. Weissa, Erik A. Petiguraa, Howard Isaacsona, Andrew W. Howardb, and Lars A. Buchhavec aDepartment of Astronomy, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720; bInstitute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, HI 96822; and cHarvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138 Edited by Adam S. Burrows, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, and accepted by the Editorial Board April 16, 2014 (received for review January 24, 2014) Small planets, 1–4× the size of Earth, are extremely common planets. The Doppler reflex velocity of an Earth-size planet − around Sun-like stars, and surprisingly so, as they are missing in orbiting at 0.3 AU is only 0.2 m s 1, difficult to detect with an − our solar system. Recent detections have yielded enough informa- observational precision of 1 m s 1. However, such Earth-size tion about this class of exoplanets to begin characterizing their planets show up as a ∼10-sigma dimming of the host star after occurrence rates, orbits, masses, densities, and internal structures. coadding the brightness measurements from each transit. The Kepler mission finds the smallest planets to be most common, The occurrence rate of Earth-size planets is a major goal of as 26% of Sun-like stars have small, 1–2 R⊕ planets with orbital exoplanet science. With three years of Kepler photometry in periods under 100 d, and 11% have 1–2 R⊕ planets that receive 1–4× hand, two groups worked to account for the detection biases in the incident stellar flux that warms our Earth. -

![Arxiv:2010.13762V1 [Astro-Ph.EP] 26 Oct 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3118/arxiv-2010-13762v1-astro-ph-ep-26-oct-2020-523118.webp)

Arxiv:2010.13762V1 [Astro-Ph.EP] 26 Oct 2020

Draft version October 27, 2020 Typeset using LATEX default style in AASTeX63 A Framework for Relative Biosignature Yields from Future Direct Imaging Missions Noah W. Tuchow 1 and Jason T. Wright 1 1Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics and Center for Exoplanets and Habitable Worlds and Penn State Extraterrestrial Intelligence Center 525 Davey Laboratory The Pennsylvania State University University Park, PA, 16802, USA ABSTRACT Future exoplanet direct imaging missions, such as HabEx and LUVOIR, will select target stars to maximize the number of Earth-like exoplanets that can have their atmospheric compositions charac- terized. Because one of these missions' aims is to detect biosignatures, they should also consider the expected biosignature yield of planets around these stars. In this work, we develop a method of computing relative biosignature yields among potential target stars, given a model of habitability and biosignature genesis, and using a star's habitability history. As an illustration and first application of this method, we use MESA stellar models to calculate the time evolution of the habitable zone, and examine three simple models for biosignature genesis to calculate the relative biosignature yield for different stars. We find that the relative merits of K stars versus F stars depend sensitively on model choice. In particular, use of the present-day habitable zone as a proxy for biosignature detectability favors young, luminous stars lacking the potential for long-term habitability. Biosignature yields are also sensitive to whether life can arise on Cold Start exoplanets that enter the habitable zone after formation, an open question deserving of more attention. Using the case study of biosignature yields calculated for θ Cygni and 55 Cancri, we find that robust mission design and target selection for HabEx and LUVOIR depends on: choosing a specific model of biosignature appearance with time; the terrestrial planet occurrence rate as a function of orbital separation; precise knowledge of stellar properties; and accurate stellar evolutionary histories. -

10. Scientific Programme 10.1

10. SCIENTIFIC PROGRAMME 10.1. OVERVIEW (a) Invited Discourses Plenary Hall B 18:00-19:30 ID1 “The Zoo of Galaxies” Karen Masters, University of Portsmouth, UK Monday, 20 August ID2 “Supernovae, the Accelerating Cosmos, and Dark Energy” Brian Schmidt, ANU, Australia Wednesday, 22 August ID3 “The Herschel View of Star Formation” Philippe André, CEA Saclay, France Wednesday, 29 August ID4 “Past, Present and Future of Chinese Astronomy” Cheng Fang, Nanjing University, China Nanjing Thursday, 30 August (b) Plenary Symposium Review Talks Plenary Hall B (B) 8:30-10:00 Or Rooms 309A+B (3) IAUS 288 Astrophysics from Antarctica John Storey (3) Mon. 20 IAUS 289 The Cosmic Distance Scale: Past, Present and Future Wendy Freedman (3) Mon. 27 IAUS 290 Probing General Relativity using Accreting Black Holes Andy Fabian (B) Wed. 22 IAUS 291 Pulsars are Cool – seriously Scott Ransom (3) Thu. 23 Magnetars: neutron stars with magnetic storms Nanda Rea (3) Thu. 23 Probing Gravitation with Pulsars Michael Kremer (3) Thu. 23 IAUS 292 From Gas to Stars over Cosmic Time Mordacai-Mark Mac Low (B) Tue. 21 IAUS 293 The Kepler Mission: NASA’s ExoEarth Census Natalie Batalha (3) Tue. 28 IAUS 294 The Origin and Evolution of Cosmic Magnetism Bryan Gaensler (B) Wed. 29 IAUS 295 Black Holes in Galaxies John Kormendy (B) Thu. 30 (c) Symposia - Week 1 IAUS 288 Astrophysics from Antartica IAUS 290 Accretion on all scales IAUS 291 Neutron Stars and Pulsars IAUS 292 Molecular gas, Dust, and Star Formation in Galaxies (d) Symposia –Week 2 IAUS 289 Advancing the Physics of Cosmic -

Cfa in the News ~ Week Ending 3 January 2010

Wolbach Library: CfA in the News ~ Week ending 3 January 2010 1. New social science research from G. Sonnert and co-researchers described, Science Letter, p40, Tuesday, January 5, 2010 2. 2009 in science and medicine, ROGER SCHLUETER, Belleville News Democrat (IL), Sunday, January 3, 2010 3. 'Science, celestial bodies have always inspired humankind', Staff Correspondent, Hindu (India), Tuesday, December 29, 2009 4. Why is Carpenter defending scientists?, The Morning Call, Morning Call (Allentown, PA), FIRST ed, pA25, Sunday, December 27, 2009 5. CORRECTIONS, OPINION BY RYAN FINLEY, ARIZONA DAILY STAR, Arizona Daily Star (AZ), FINAL ed, pA2, Saturday, December 19, 2009 6. We see a 'Super-Earth', TOM BEAL; TOM BEAL, ARIZONA DAILY STAR, Arizona Daily Star, (AZ), FINAL ed, pA1, Thursday, December 17, 2009 Record - 1 DIALOG(R) New social science research from G. Sonnert and co-researchers described, Science Letter, p40, Tuesday, January 5, 2010 TEXT: "In this paper we report on testing the 'rolen model' and 'opportunity-structure' hypotheses about the parents whom scientists mentioned as career influencers. According to the role-model hypothesis, the gender match between scientist and influencer is paramount (for example, women scientists would disproportionately often mention their mothers as career influencers)," scientists writing in the journal Social Studies of Science report (see also ). "According to the opportunity-structure hypothesis, the parent's educational level predicts his/her probability of being mentioned as a career influencer (that ism parents with higher educational levels would be more likely to be named). The examination of a sample of American scientists who had received prestigious postdoctoral fellowships resulted in rejecting the role-model hypothesis and corroborating the opportunity-structure hypothesis. -

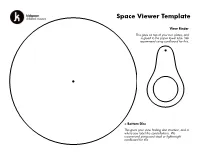

Space Viewer Template

Space Viewer Template View Finder This goes on top of your two plates, and is glued to the paper towel tube. We recommend using cardboard for this. < Bottom Disc This gives your view finding disc structure, and is where you label the constellations. We recommend using card stock or lightweight cardboard for this. Constellation Plate > This disc is home to your constellations, and gets glued to the larger disc. We recommend using paper for this, so the holes are easier to punch. Use the punch guides on the next page to punch holes and add labels to your viewer. Orion Cancer Look for the middle star of Orions When you look at this constellation, look sword, that is an area of brighter nearby for 55 Cancri a star that has light, it’s actually a nebula! The five exoplanets orbiting it. One of those Orion Nebula is a gigantic cloud of plants (55 Cancri e) is a super hot dust and gas, where new stars are planet entirely covered in an ocean of being created. lava! Cygnus Andromeda This constellation is home to the This constellation is very close to the Kepler-186 system, including the Andromeda Galaxy (an enormous planet Kepler-186f. Seen by collection of gas, dust, and billions of NASA's Kepler Space Telescope, stars and solar systems). This spiral this is the first Earth-sized planet galaxy is so bright, you can spot it with discovered that is in"habitable the naked eye! zone" of its star. Ursa Minor Cassiopeia Ursa Minor has two stars known While gazing at Cassiopeia look for with exoplanets orbiting them - the“Pacman Nebula” (It’s official name both are gas giants, that are much is NGC 281). -

A Case for an Atmosphere on Super-Earth 55 Cancri E

The Astronomical Journal, 154:232 (8pp), 2017 December https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-3881/aa9278 © 2017. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. A Case for an Atmosphere on Super-Earth 55 Cancri e Isabel Angelo1,2 and Renyu Hu1,3 1 Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, CA 91109, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Astronomy, University of California, Campbell Hall, #501, Berkeley CA, 94720, USA 3 Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA Received 2017 August 2; revised 2017 October 6; accepted 2017 October 8; published 2017 November 16 Abstract One of the primary questions when characterizing Earth-sized and super-Earth-sized exoplanets is whether they have a substantial atmosphere like Earth and Venus or a bare-rock surface like Mercury. Phase curves of the planets in thermal emission provide clues to this question, because a substantial atmosphere would transport heat more efficiently than a bare-rock surface. Analyzing phase-curve photometric data around secondary eclipses has previously been used to study energy transport in the atmospheres of hot Jupiters. Here we use phase curve, Spitzer time-series photometry to study the thermal emission properties of the super-Earth exoplanet 55 Cancri e. We utilize a semianalytical framework to fit a physical model to the infrared photometric data at 4.5 μm. The model uses parameters of planetary properties including Bond albedo, heat redistribution efficiency (i.e., ratio between radiative timescale and advective timescale of the atmosphere), and the atmospheric greenhouse factor. -

FY13 High-Level Deliverables

National Optical Astronomy Observatory Fiscal Year Annual Report for FY 2013 (1 October 2012 – 30 September 2013) Submitted to the National Science Foundation Pursuant to Cooperative Support Agreement No. AST-0950945 13 December 2013 Revised 18 September 2014 Contents NOAO MISSION PROFILE .................................................................................................... 1 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 2 2 NOAO ACCOMPLISHMENTS ....................................................................................... 4 2.1 Achievements ..................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Status of Vision and Goals ................................................................................. 5 2.2.1 Status of FY13 High-Level Deliverables ............................................ 5 2.2.2 FY13 Planned vs. Actual Spending and Revenues .............................. 8 2.3 Challenges and Their Impacts ............................................................................ 9 3 SCIENTIFIC ACTIVITIES AND FINDINGS .............................................................. 11 3.1 Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory ....................................................... 11 3.2 Kitt Peak National Observatory ....................................................................... 14 3.3 Gemini Observatory ........................................................................................