Another, More Sinister Reality Jbftv

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

The Influence of Kitchen Sink Drama in John Osborne's

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 23, Issue 9, Ver. 7 (September. 2018) 77-80 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org The Influence of Kitchen Sink Drama In John Osborne’s “ Look Back In Anger” Sadaf Zaman Lecturer University of Bisha Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Corresponding Author: Sadaf Zaman ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- Date of Submission:16-09-2018 Date of acceptance: 01-10-2018 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------------- John Osborne was born in London, England in 1929 to Thomas Osborne, an advertisement writer, and Nellie Beatrice, a working class barmaid. His father died in 1941. Osborne used the proceeds from a life insurance settlement to send himself to Belmont College, a private boarding school. Osborne was expelled after only a few years for attacking the headmaster. He received a certificate of completion for his upper school work, but never attended a college or university. After returning home, Osborne worked several odd jobs before he found a niche in the theater. He began working with Anthony Creighton's provincial touring company where he was a stage hand, actor, and writer. Osborne co-wrote two plays -- The Devil Inside Him and Personal Enemy -- before writing and submittingLook Back in Anger for production. The play, written in a short period of only a few weeks, was summarily rejected by the agents and production companies to whom Osborne first submitted the play. It was eventually picked up by George Devine for production with his failing Royal Court Theater. Both Osborne and the Royal Court Theater were struggling to survive financially and both saw the production of Look Back in Anger as a risk. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

It's a Conspiracy

IT’S A CONSPIRACY! As a Cautionary Remembrance of the JFK Assassination—A Survey of Films With A Paranoid Edge Dan Akira Nishimura with Don Malcolm The only culture to enlist the imagination and change the charac- der. As it snows, he walks the streets of the town that will be forever ter of Americans was the one we had been given by the movies… changed. The banker Mr. Potter (Lionel Barrymore), a scrooge-like No movie star had the mind, courage or force to be national character, practically owns Bedford Falls. As he prepares to reshape leader… So the President nominated himself. He would fill the it in his own image, Potter doesn’t act alone. There’s also a board void. He would be the movie star come to life as President. of directors with identities shielded from the public (think MPAA). Who are these people? And what’s so wonderful about them? —Norman Mailer 3. Ace in the Hole (1951) resident John F. Kennedy was a movie fan. Ironically, one A former big city reporter of his favorites was The Manchurian Candidate (1962), lands a job for an Albu- directed by John Frankenheimer. With the president’s per- querque daily. Chuck Tatum mission, Frankenheimer was able to shoot scenes from (Kirk Douglas) is looking for Seven Days in May (1964) at the White House. Due to a ticket back to “the Apple.” Pthe events of November 1963, both films seem prescient. He thinks he’s found it when Was Lee Harvey Oswald a sleeper agent, a “Manchurian candidate?” Leo Mimosa (Richard Bene- Or was it a military coup as in the latter film? Or both? dict) is trapped in a cave Over the years, many films have dealt with political conspira- collapse. -

ULUSLARARASI AVRASYA SOSYAL BİLİMLER DERGİSİ MART/MARCH Yıl/Year: 6, Cilt/Vol:6, Sayı/Issue: 18 2015

ULUSLARARASI AVRASYA SOSYAL BİLİMLER DERGİSİ MART/MARCH Yıl/Year: 6, Cilt/Vol:6, Sayı/Issue: 18 2015 ALIENATION IN ROOM AT THE TOP: JOE LAMPTON’S TRANSFORMATION INTO THE STEREOTYPICAL OTHERS OF HIS MIND Mustafa DEMİREL Arş. Gör. Ege Edebiyat Fakültesii İngiliz Dili ve Edebiyatı, [email protected] ABSTRACT Throughout this study, Joe Lampton is examined as a model hero of the "Angry Young Men" movement in the post-war Britain. In the first place, the movement and its basic notions are explained; then, the attention is directed to the patterns of hero of the 1950s' fictions. After the reasons of alienation for those models of hero are posed, the paper deals with Joe Lampton's particular case of disappointment and alienation. For the rest part of the study, Joe Lampton's psyche, which is full of self-created imaginary conceptions, is at the center. Through a comparative stance to his past and present mindset, it is claimed that after a while, the protagonist becomes the victim of his own stereotypical characters. The dilemma between his lower status based on his past and his new identity adopted among the upper classes brings about an ambiguity for both the identity of the protagonist and the end of the story. Key Words: Alienation, angry young men, class, identity, stereotype. TEPEDEKİ ODA'DAKİ YABANCILAŞMA: JOE LAMPTON'IN ZİHNİNDEKİ STEREOTİP ÖTEKİLERE DÖNÜŞÜMÜ ÖZET Bu çalışmada, Joe Lampton savaş sonrası İngiltere'sindeki "Öfkeli Genç Adamlar" hareketinin kahraman modeli olarak incelenir. İlk olarak hareket ve onun temel kavramları açıklanır, daha sonra 1950'lerin romanlarının kahraman modellerine dikkat çekilir. -

Valkyrie Talent

Valkyrie Talent: Tom Cruise, Bill Nighy, Terence Stamp, Tom Wilkinson, Clarice van Houten, Kenneth Branagh, David Bamber, Thomas Kretschmann, Eddie Izzard. Date of review: Thursday 22nd January, 2009 Director: Bryan Singer Duration: 122 minutes Classification: M We rate it: 2 and a half stars. Valkyrie has been widely billed as the first of Tom Cruise’s steps back into the A-list stratosphere. After all the couch-jumping, manager-firing, studio-hopping, Scientology-spouting weirdness, Tom has apparently decided to get his career back on track (despite the fact that it is arguably in quite good shape, with the star sporting a recent Golden Globe nomination for his quite hilarious turn in Ben Stiller’s Tropic Thunder). Valkyrie is indeed a very serious and sombre film, and despite the fact that it’s backed by a healthy budget, it is a film that is all about performances, so with all of that in mind, it does seem like a decent choice for an actor bent on returning to centre stage. Valkyrie is one of many recent films that tells a story about World War II as a good old espionage thriller, replete with the odd reflection upon some of our contemporary world’s conflicts. The film’s plot revolves around one of the numerous attempts that Germans army officers made to assassinate Adolf Hitler. Anyone who knows his or her history knows that there were quite a few attempts to kill the Nazi leader, but it’s of course also a widely known fact that Hitler survived all of those attempts, and the he suicided when the Allied victory became apparent. -

An Overview of the Working Classes in British Feature Film from the 1960S to the 1980S: from Class Consciousness to Marginalization

An Overview of the Working Classes in British Feature Film from the 1960s to the 1980s: From Class Consciousness to Marginalization Stephen C. Shafer University of Illinois Abstract The portrayal of the working classes has always been an element of British popular film from the comic music hall stereotypes in the era of Gracie Fields and George Formby in the 1930s to the more gritty realism of the “Angry Young Man” films that emerged in the 1950s and 1960s. Curiously, in the last thirty years, the portrayal of the working classes in popular film has become somewhat less sharply drawn and more indistinct. In an odd way, these changes may parallel criticisms directed toward politicians about a declining sense of working-class unity and purpose in the wake of the Margaret Thatcher and post-Thatcher eras. When noted English film director and commentator Lindsay Anderson was asked to contribute an overview article on the British cinema for the 1984 edi- tion of the International Film Guide, he ruefully observed that from the per- spective of 1983 and, indeed, for most of its history, “British Cinema [has been] . a defeated rather than a triumphant cause.”1 Referring to the perennial fi- nancial crises and the smothering effect of Hollywood’s competition and influ- ence, Anderson lamented the inability of British films to find a consistent na- tional film tradition, adding that “the British Cinema has reflected only too clearly a nation lacking in energy and the valuable kind of pride . which cher- ishes its own traditions.”2 In particular, Anderson observed that when, on occa- sion, the British film industry had attempted to address the interests and needs of its working classes, the “aims” of the film-makers “were not supported . -

Elisabeth Shue and Terence Stamp Star in Cult Fantasy Horror “LINK” (15)

Elisabeth Shue and Terence Stamp Star in Cult Fantasy Horror “LINK” (15) From the director of Cloak and Dagger, Terence Stamp (The Limey) is single-minded professor Dr Steven Phillip who sets in motion a terrifying chain of events for Elizabeth Shue (Hollow Man) in the UK DVD release of LINK (15). Available as a brand-new transfer from the original film elements, it is available to own on 26 August 2013, RRP £9.99. Jane (Shue), an American zoology student, takes a summer job at the lonely cliff-top home of a professor who is exploring the link between man and ape. Soon after her arrival he vanishes, leaving her to care for his three chimps: Voodoo, a savage female; the affectionate, child-like Imp; and Link – a circus ape trained as the perfect servant and companion. Soon a disturbing role reversal takes place in the relationship between master and servant and Jane becomes a prisoner in a simian house of horror. In her attempts to escape she’s up against an adversary several times her physical strength – and the instincts of a bloodthirsty killer… With a score from Oscar-winning composer Jerry Goldsmith (The Omen), this suspense thriller from Richard Franklin is a horror classic which will make you go ape with fear. Special Features Instant Play feature Stills gallery Promotional PDFs. ENDS NOTES TO EDITOR LINK (15) Release Date: 26 August 2013 RRP: £9.99 Running Time: 112 mins (approx.) Screen Ratios: 1.66.1 (colour) No. of Discs: 1 Catalogue no. 7953930 For further information visit: www.networkonair.com www.facebook.com/TheBritishFilm www.twitter.com/networktweets #TheBritishFilm For media enquiries contact: Luciano Chelotti, Sabina Maharjan Network, 19-20 Berghem Mews, Blythe Road, London, W14 0HN Tel: 020 7605 4422 or 020 7605 4424 Fax: 020 7605 4421 Email [email protected] or [email protected]. -

Room at the Top Free

FREE ROOM AT THE TOP PDF John Braine | 240 pages | 15 Jun 2005 | Cornerstone | 9780099445364 | English | London, United Kingdom Room at the Top (novel) - Wikipedia Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Room at the Top to Read Room at the Top Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh Room at the Top try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — Room at the Top by John Braine. The ruthlessly ambitious Joe Lampton rises swiftly from the petty bureaucracy of local government into the world of inherited wealth, fast cars, and glamorous women. But betrayal and tragedy strike as the original 'angry young man' of the fifties pursues his goals. Get A Copy. Published by Methuen Publishing first published More Details Original Title. Yorkshire, England. Other Editions Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Room at the Topplease sign Room at the Top. Read this book when I was 13 and it was an immediate pack of wallop. Now I have a different question; Which Warley? There are several of them over here! Mymymble It's fictional. The excellent film was shot mainly in Halifax. Is there a sequel novel? There are two films about Joe Lamptob. Greg The sequel is called, "Life at the Top". See 2 questions about Room at the Top…. Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 3. -

Frenchlieutenantswom

Virtual April 6, 2021 (42:10) Karel Reisz: THE FRENCH LIEUTENANT’S WOMAN (1981, 124 min) Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. Cast and crew name hyperlinks connect to the individuals’ Wikipedia entries Vimeo link for ALL of Bruce Jackson’s and Diane Christian’s film introductions and post-film discussions in the virtual BFS Vimeo link for our introduction to The French Lieutenant’s Woman Zoom link for all Spring 2021 BFS Tuesday 7:00 PM post-screening discussions: Meeting ID: 925 3527 4384 Passcode: 820766 Directed by Karel Reisz Based on the novel by John Fowles Screenplay by Harold Pinter Produced by Leon Clore Original Music by Carl Davis Cinematography by Freddie Francis Liz Smith....Mrs. Fairley The film was nominated for five Oscars, including Patience Collier....Mrs. Poulteney Best Actress in a Leading Role (Meryl Streep) and David Warner....Murphy Best Writing, Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium (Harold Pinter), at the 1982 Karel Reisz (21 July 1926, Ostrava, Academy Awards. Czechoslovakia—25 November 2002, London, England) directed 13 theatrical and tv films: “Act Meryl Streep....Sarah/Anna Without Words I” (2000), The Deep Blue Sea (1994), Jeremy Irons....Charles Henry Smithson/Mike Everybody Wins (1990), Sweet Dreams (1985), The Hilton McRae....Sam French Lieutenant's Woman (1981), Who'll Stop the Emily Morgan....Mary Rain (1978), The Gambler (1974), Isadora (1968), Charlotte Mitchell....Mrs. Tranter Morgan (1966), Night Must Fall (1964), Saturday Lynsey Baxter....Ernestina Night and Sunday Morning (1960), We Are the Jean Faulds....Cook Lambeth Boys (1958) and Momma Don't Allow Peter Vaughan ....Mr. -

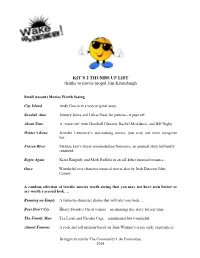

Jim Kitendaugh's Highly Acclaimed Movie List

KIT’S 2 THUMBS UP LIST thanks to movie mogul Jim Kitendaugh Small (recent) Movies Worth Seeing City Island Andy Garcia in a very original story. Swedish Auto January Jones and Lukas Haas; be patient—it pays off. About Time A “must see” with Domhall Gleeson, Rachel McAdams, and Bill Nighy. Winter’s Bone Jennifer Lawrence’s star-making movie; you may not even recognize her. Frozen River Melissa Leo’s Oscar-nominated performance; an unusual story brilliantly rendered. Begin Again Keira Knightly and Mark Ruffalo in an off-kilter musical/romance. Once Wonderful two-character musical movie also by Irish Director John Carney. A random selection of terrific movies worth seeing that you may not have seen before or are worth a second look…. Running on Empty A fantastic character drama that will take you back…. Boys Don’t Cry Hilary Swank’s Oscar winner—an amazing true story for our time. The Family Man Tea Leoni and Nicolas Cage—sentimental but wonderful. Almost Famous A rock and roll memoir based on Jann Wenner’s crazy early experiences. Brought to you by The Community Life Committee 2018 True Grit (2010) The 1970 version was fun; this version is good; Jeff Bridges. They Won’t Forget Unbelievable movie based on Leo Frank’s trial for the murder of Mary Phagan; Lana Turner’s film debut. Road to Perdition Tom Hanks cast against type; Paul Newman’s last movie; extraordinary story-telling and cinematography. Nashville Country music, the bicentennial, politics, a mosaic of 24 fascinating characters—Robert Altman’s masterpiece. King Kong (1933) Not just a curiosity—a great movie with a caveat: portrayals/caricatures of native islanders are typical of the time. -

Five Films of Steven Soderbergh Donald Beale Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2003 Five films of Steven Soderbergh Donald Beale Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Beale, Donald, "Five films of Steven Soderbergh" (2003). LSU Master's Theses. 1469. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/1469 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FIVE FILMS OF STEVEN SODERBERGH A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Arts in The Interdepartmental Program in Liberal Arts by Donald Beale B.A., Pennsylvania State University, 1982 August 2003 Acknowledgments As an employee of the LSU Office of Independent Study, I owe my thanks to my supervisor, Kathryn Carroll, Assistant Director for Instructional Support and Publications, and to Dr. Ronald S. McCrory, Director, for their support and for providing an environment that encourages and accommodates staff members’ enrollment in university courses and pursuit of a degree. Jeffrey A. Long, P.E., cherished friend for more than two decades, provided a piece of technical information as well as the occasional note of encouragement. I cannot exaggerate my debt of gratitude to John D.