Hack, Sputter, Wheeze… Herbs to Help You Cough

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Comparative Evaluation of Dietary Oregano, Anise and Olive

Revista Brasileira de Ciência Avícola ISSN: 1516-635X [email protected] Fundação APINCO de Ciência e Tecnologia Avícolas Brasil Christaki, EV; Bonos, EM; Florou-Paneri, PC Comparative evaluation of dietary oregano, anise and olive leaves in laying Japanese quails Revista Brasileira de Ciência Avícola, vol. 13, núm. 2, abril-junio, 2011, pp. 97-101 Fundação APINCO de Ciência e Tecnologia Avícolas Campinas, SP, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=179719101003 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Brazilian Journal of Poultry Science Revista Brasileira de Ciência Avícola Comparative Evaluation of Dietary Oregano, Anise ISSN 1516-635X Apr - Jun 2011 / v.13 / n.2 / 97-101 and Olive Leaves in Laying Japanese Quails nAuthor(s) ABSTRACT Christaki EV Bonos EM Aim of the present study was the comparative evaluation of the Florou-Paneri PC effect of ground oregano, anise and olive leaves as feed additives on Laboratory of Nutrition performance and some egg quality characteristics of laying Japanese Faculty of Veterinary Medicine quails. A total of 189 Coturnix japonica quails (126 females and 63 Aristotle University of Thessaloniki Thessaloniki, Greece males), 149 days old, were randomly allocated into seven equal groups with three subgroups of 9 birds each (6 females and 3 males). A commercial laying diet was fed to the control group. The remaining six groups were fed the same diet supplemented with oregano at 10 g/kg or 20 g/kg, anise at 10 g/kg or 20 g/kg and olive leaves at 10 g/ kg or at 20 g/kg. -

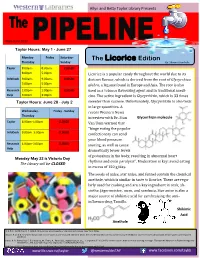

The Licorice Edition

Allyn and Betty Taylor Library Presents May-June 2017 Taylor Hours: May 1 - June 27 Monday- Friday Saturday- The Licorice Edition Thursday Sunday By: Shawn Hendrikx Taylor 8:00am- 8:00am- CLOSED 8:00pm 5:00pm Licorice is a popular candy throughout the world due to its InfoDesk 9:00am- 9:00am- CLOSED distinct flavour, which is derived from the root of Glycyrrhiza 5:00pm 5:00pm glabra, a legume found in Europe and Asia. The root is also Research 1:00pm- 1:00pm- CLOSED used as a tobacco flavouring agent and in traditional medi- Help 3:00pm 3:00pm cine. The active ingredient is Glycyrrhizin, which is 33 times Taylor Hours: June 28 - July 2 sweeter than sucrose. Unfortunately, Glycyrrhizin is also toxic in large quantities. A Wednesday- Friday - Sunday recent Western News Thursday interview with Dr. Stan Glycerrhizin molecule Taylor 8:00am-5:00pm CLOSED Van Uum warned that “binge eating the popular InfoDesk 9:00am- 5:00pm CLOSED confectionary can send your blood pressure Research 1:00pm-3:00pm CLOSED soaring, as well as cause Help dramatically lower levels of potassium in the body, resulting in abnormal heart Monday May 22 is Victoria Day rhythms and even paralysis”. Moderation is key: avoid eating The Library will be CLOSED in excess of 150 g/day. The seeds of anise, star anise, and fennel contain the chemical anethole, which is similar in taste to licorice. These are regu- larly used for cooking and are a key ingredient in arak, ab- sinthe, Ja germeister, ouzo, and sambuca. Star anise is also a major source of shikimic acid for synthesizing the anti- influenza drug Tamiflu. -

Fragrant Herbs for Your Garden

6137 Pleasants Valley Road Vacaville, CA 95688 Phone (707) 451-9406 HYPERLINK "http://www.morningsunherbfarm.com" www.morningsunherbfarm.com HYPERLINK "mailto:[email protected]" [email protected] Fragrant Herbs For Your Garden Ocimum basilicum – Sweet, or Genovese basil; classic summer growing annual Ocimum ‘Pesto Perpetuo’ – variegated non-blooming basil! Ocimum ‘African Blue’ - sterile Rosmarinus officinalis ‘Blue Spires’ – upright grower, with large leaves, beautiful for standards Salvia officinalis ‘Berggarten’ – sun; classic culinary, with large gray leaves, very decorative Thymus vulgaris ‘English Wedgewood’ – sturdy culinary, easy to grow in ground or containers Artemesia dracunculus var sativa – French tarragon; herbaceous perennial. Absolutely needs great drainage! Origanum vulgare – Italian oregano, popular oregano flavor, evergreen; Greek oregano - strong flavor Mentha spicata ‘Kentucky Colonel’ – one of many, including ginger mint and orange mint Cymbopogon citratus – Lemon grass, great for cooking, and for dogs Aloysia triphylla – Lemon verbena ; Aloysia virgata – Sweet Almond Verbena – almond scented! Polygonum odoratum – Vietnamese coriander, a great perennial substitute for cilantro Agastache foeniculum ‘Blue Fortune’ – Anise hyssop, great for teas, honebee plant Agastache ‘Coronado’; A. Grape Nectar’ – both are 18 inches, delicious for tea, edible flr Agastache ‘Summer Breeze’ – large growing, full sun, bicolored pink and coral flowers Prostanthera rotundifolium – Australian Mint Bush. -

Chest Pain and Non-Respiratory Symptoms in Acute Asthma

Postgrad Med J 2000;76:413–414 413 Chest pain and non-respiratory symptoms in Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pmj.76.897.413 on 1 July 2000. Downloaded from acute asthma W M Edmondstone Abstract textbooks. Occasionally the combination of The frequency and characteristics of chest dyspnoea and chest pain results in diagnostic pain and non-respiratory symptoms were confusion. This study was prompted by the investigated in patients admitted with observation that a number of patients admitted acute asthma. One hundred patients with with asthmatic chest pain had been suspected a mean admission peak flow rate of 38% of having cardiac ischaemia, pleurisy, pericardi- normal or predicted were interviewed tis, or pulmonary embolism. It had also been using a questionnaire. Chest pain oc- observed that many patients admitted with curred in 76% and was characteristically a asthma complained of a range of non- dull ache or sharp, stabbing pain in the respiratory symptoms, something which has sternal/parasternal or subcostal areas, been noted previously in children1 and in adult worsened by coughing, deep inspiration, asthmatics in outpatients.2 The aim of this or movement and improved by sitting study was to examine the frequency and char- upright. It was rated at or greater than acteristics of chest pain and other symptoms in 5/10 in severity by 67% of the patients. A patients admitted with acute asthma. wide variety of upper respiratory and sys- temic symptoms were described both Patients and methods before and during the attack. One hundred patients (66 females, mean (SD) Non-respiratory symptoms occur com- age 45.0 (19.7) years) admitted with acute monly in the prodrome before asthma asthma were studied. -

Chemical Composition and Antifungal Effect of Anise (Pimpinella Anisum L.) Fruit Oil at Ripening Stage

Annals of Microbiology, 56 (4) 353-358 (2006) Chemical composition and antifungal effect of anise (Pimpinella anisum L.) fruit oil at ripening stage Mehmet Musa ÖZCAN1*, Jean Claude CHALCHAT2 1Department of Food Engineering, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Selcuk, 42031 Konya, Turkey; 2Laboratoire de Chimie des Huiles Essentielles, Universite Blaise Pascal de Clermont, 63177 Aubiere Cedex, France Received 1 June 2006 / Accepted 25 October 2006 Abstract -The composition of the essential oil of Pimpinella anisum L fruit is determined by GC and GC-MS. The volatile oil content obtained by hydrodistillation was 1.91%. Ten compounds representing 98.3% of the oil was identified. The main constituents of the oil obtained from dried fruits were trans-anethole (93.9%) and estragole (2.4%). The olfactorially valuable constituents that were found with concentration higher than 0.06% were (E)-methyeugenol, α-cuparene, α-himachalene, β-bisabolene, p-anisaldehyde and cis-anet- hole. Also, the different concentrations of anise oil exerted varying levels of inhibitory effects on the mycelial growth of Alternaria alter- nata, Aspergillus niger and Aspergillus parasiticus used in experimental. The results showed that the most effected fungus from anise oil was A. parasiticus, which is followed by A. niger and A. alternata. Individual of this plant oil may provide a useful to achive adequate shelf-life of foods. Key words: anise, Pimpinella anisum, essential oil, composition, trans-anethole, fungi, inhibitory effect. INTRODUCTION Spices, herbs and their derivatives are used in foods for their flavours and aroma (Dorman and Deans, 2000). The Anise (Pimpinella anisum L.), belonging to the Umbelliferae chemical composition of essential oil of several Pimpinella family is an annual herbaceous and a typical aromatic plant, species has been studied (Embong et al., 1977; Ashraf et al., which grows in several regions all over the world (Omidbai- 1980; Ivanic et al., 1983; Lawrence, 1984; Bas,er and Özek, gi et al., 2003; Rodrigues et al., 2003; Askari et al., 2005). -

Spice Basics

SSpicepice BasicsBasics AAllspicellspice Allspice has a pleasantly warm, fragrant aroma. The name refl ects the pungent taste, which resembles a peppery compound of cloves, cinnamon and nutmeg or mace. Good with eggplant, most fruit, pumpkins and other squashes, sweet potatoes and other root vegetables. Combines well with chili, cloves, coriander, garlic, ginger, mace, mustard, pepper, rosemary and thyme. AAnisenise The aroma and taste of the seeds are sweet, licorice like, warm, and fruity, but Indian anise can have the same fragrant, sweet, licorice notes, with mild peppery undertones. The seeds are more subtly fl avored than fennel or star anise. Good with apples, chestnuts, fi gs, fi sh and seafood, nuts, pumpkin and root vegetables. Combines well with allspice, cardamom, cinnamon, cloves, cumin, fennel, garlic, nutmeg, pepper and star anise. BBasilasil Sweet basil has a complex sweet, spicy aroma with notes of clove and anise. The fl avor is warming, peppery and clove-like with underlying mint and anise tones. Essential to pesto and pistou. Good with corn, cream cheese, eggplant, eggs, lemon, mozzarella, cheese, olives, pasta, peas, pizza, potatoes, rice, tomatoes, white beans and zucchini. Combines well with capers, chives, cilantro, garlic, marjoram, oregano, mint, parsley, rosemary and thyme. BBayay LLeafeaf Bay has a sweet, balsamic aroma with notes of nutmeg and camphor and a cooling astringency. Fresh leaves are slightly bitter, but the bitterness fades if you keep them for a day or two. Fully dried leaves have a potent fl avor and are best when dried only recently. Good with beef, chestnuts, chicken, citrus fruits, fi sh, game, lamb, lentils, rice, tomatoes, white beans. -

Growing Hummingbird Mint in Utah Gardens Taun Beddes and Michael Caron

October 2017 Horticulture/Garden/2017-02pr Growing Hummingbird Mint in Utah Gardens Taun Beddes and Michael Caron Quick Facts Introduction • Hummingbird mints are a group of Most hummingbird mint species (Agastache spp.) ornamental herbaceous perennials that are native to the American Southwest and Mexico. bloom from early summer to fall, in colors They are members of the mint family, but do not ranging from pink, red, orange, purple, blue, aggressively spread like spearmint and peppermint. and yellow. Most are cold-hardy along the Wasatch Front, Moab • They are popular with various pollinators and St. George. Many also grow in colder areas of including hummingbirds and butterflies. Utah, but care must be taken to be sure. Table 1 lists • Most cultivars grow to 18-36 inches tall and common species, USDA hardiness zones, mature wide depending on the cultivar. size, and flower colors. Many cultivars and hybrids • They tolerate full sun and grow in most soils have been created that have given more variety to if the soil is not waterlogged. their flower colors and mature sizes than is shown • They do not require frequent irrigation once in the table. Residents can find their hardiness zone established. at www.forestry.usu.edu/trees-cities-towns/tree- selection/hardiness-zone Table 1. Selected common hummingbird mint species. Species USDA Mature Size Flower Color Hardiness Zone Orange hummingbird mint 5 - 8 12-30 inches tall, 12-24 Yellow, red, orange (Agastache aurantiaca) inches wide Texas hummingbird mint 5 - 8 18-36 inches tall, 12-24 Violet, blue, rose, red (A. cana) inches wide Cusick’s hyssop 4 – 8 6 – 12 inches tall and wide Light purple (A. -

Management of Wheeze and Cough in Infants and Pre-Schoo L Children In

nPersonal opinio lManagement of wheeze and cough in infants and pre-schoo echildren in primary car Pauln Stephenso nIntroductio is, well established in adults 2thoughs there remain somer controversy about its diagnosis in children eve Managementa of wheeze and cough in children is sinceh Spelman's uncontrolled study of children wit commonm problem in primary care. In this paper I ai nchronic cough successfully treated according to a tod provide a few useful management tools with regar .asthma protocol 3gWithout the ability to perform lun toe diagnosis, the role of a trial of treatment, and th functione tests in pre-school children, care must b rationalee for referral. For an in-depth review see th takent to exclude other diagnoses. A persisten article. in this journal two years ago by Bush 1 eproductiv coughc may be due solely to chroni catarrhe with postnasal drip, but early referral may b sPresentation of Symptom needed. A persistent dry cough,n worse at night and o exercise,s and without evidence of other diagnose Ity is always worth asking parents what they mean b warrants. a trial of asthma treatment thed term 'wheeze' or 'cough'. The high-pitche musicaln noise of a wheeze usually on expiratio Thef younger the child, the longer the list o shouldy not be confused with the sound of inspirator differentialo diagnoses and the more one has t sstridor. The sound of airflow through secretions i econsider possibilities other than 'asthma'. Thes ddifferent again, and parents may describe their chil linclude upper airways disease, congenital structura 'vomiting'g when, in fact, the child has been coughin diseasel of the bronchi, bronchial or trachea severely and bringing up phlegm or mucus. -

Gas Exchange and Respiratory Function

LWBK330-4183G-c21_p484-516.qxd 23/07/2009 02:09 PM Page 484 Aptara Gas Exchange and 5 Respiratory Function Applying Concepts From NANDA, NIC, • Case Study and NOC A Patient With Impaired Cough Reflex Mrs. Lewis, age 77 years, is admitted to the hospital for left lower lobe pneumonia. Her vital signs are: Temp 100.6°F; HR 90 and regular; B/P: 142/74; Resp. 28. She has a weak cough, diminished breath sounds over the lower left lung field, and coarse rhonchi over the midtracheal area. She can expectorate some sputum, which is thick and grayish green. She has a history of stroke. Secondary to the stroke she has impaired gag and cough reflexes and mild weakness of her left side. She is allowed food and fluids because she can swallow safely if she uses the chin-tuck maneuver. Visit thePoint to view a concept map that illustrates the relationships that exist between the nursing diagnoses, interventions, and outcomes for the patient’s clinical problems. LWBK330-4183G-c21_p484-516.qxd 23/07/2009 02:09 PM Page 485 Aptara Nursing Classifications and Languages NANDA NIC NOC NURSING DIAGNOSES NURSING INTERVENTIONS NURSING OUTCOMES INEFFECTIVE AIRWAY CLEARANCE— RESPIRATORY MONITORING— Return to functional baseline sta- Inability to clear secretions or ob- Collection and analysis of patient tus, stabilization of, or structions from the respiratory data to ensure airway patency improvement in: tract to maintain a clear airway and adequate gas exchange RESPIRATORY STATUS: AIRWAY PATENCY—Extent to which the tracheobronchial passages remain open IMPAIRED GAS -

Chief Compaint/HPI History

PULMONOLOGY ASSOCIATES OF TEXAS 6860 North Dallas Pkwy, Ste 200, Plano, TX 75024 Tel: 469-305-7171 Fax: 469-212-1548 Patient Name: Thomas Cromwell Patient DOB: 02-09-1960 Patient Sex: Male Visit Date: 03-06-2016 Chief Compaint/HPI Chief Complaint: Shortness of Breath History of Present Illness: he patient is an 56-year-old male. From the last few days, he is not feeling well. Complains of fatigue, tiredness, weakness, nausea, no vomiting, no hematemesis or melena. The patient relates to have some low-grade fever. The patient came to the emergency room. Initially showed atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. It appears that the patient has chronic atrial fibrillation. As per the medications, they are not very clear. He denies any specific chest pain. Her main complaint is shortness of breath and symptoms as above Pulmonary symptoms: cough, sputum, no hemoptysis, dyspnea and wheezing. History Past Medical History: Pulmonary history includes pneumonia and sleep apnea. Cardiac history includes atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure. Remainder of PMH is non-significant. Surgical History: appendectomy in 2007. Medications: Pulmonary medications are albuterol and Spiriva; Cardiac medications include: atenolol and digoxin; Family History: Father is deceased at age 80. Father PMH remarkable for CHF, hypertension and MI; Mother is alive. Mother PMH remarkable for alzheimers, diabetes and hypertension; Cancer history in family: No Lung disease in the family: No Social History: Current every day smoker - 1 pack / day Alcohol consumption: social Marital status: lives alone Exposure History: Occupation: farmer. Asbestos exposure: None. No exposure to Ground Zero. Immunization History: Patient has an immunization history of flu shot, H1N1shot and pneumococcal shot. -

Approach to Type 2 Respiratory Failure Changing Nature of NIV

Approach to type 2 Respiratory Failure Changing Nature of NIV • Not longer just the traditional COPD patients • Increasingly – Obesity – Neuromuscular – Pneumonias • 3 fold increase in patients with Ph 7.25 and below Impact • Changing guidelines • Increased complexity • Increased number of patients • Decreased threshold for initiation • Lower capacity for ITU to help • Higher demands on nursing staff Resp Failure • Type 1 Failure of Oxygenation • Type 2 Failure of Ventilation • Hypoventilation • Po2 <8 • Pco2 >6 • PH low or bicarbonate high Ventilation • Adequate Ventilation – Breathe in deeply enough to hit a certain volume – Breathe out leaving a reasonable residual volume – Breath quick enough – Tidal volume and minute ventilation Response to demand • Increase depth of respiration • Use Reserve volume • Increase rate of breathing • General increase in minute ventilation • More gas exchange Failure to match demand • Hypoventilation • Multifactorial • Can't breathe to a high enough volume • Can't breath quick enough • Pco2 rises • Po2 falls Those at risk • COPD • Thoracic restriction • Central • Neuromuscular • Acute aspects – Over oxygenation – Pulmonary oedema Exhaustion • Complicates all forms of resp failure • Type one will become type two • Needs urgent action • Excessive demand • Unable to keep up • Resp muscle hypoxia Exhaustion • Muscles weaken • Depth of inspiration drops • Residual volume drops • Work to breath becomes harder • Spiral of exhaustion • Pco2 rises, Po2 drops Type 2 Respiratory Failure Management Identifying Those -

Consumption Impact of Some Rich Phytoestrogen Plant Foods on Menstrual Disturbance for Undergraduate Girl Students

World Applied Sciences Journal 34 (12): 1888-1896, 2016 ISSN 1818-4952 © IDOSI Publications, 2016 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.wasj.2016.1888.1896 Consumption Impact of Some Rich Phytoestrogen Plant Foods on Menstrual Disturbance for Undergraduate Girl Students 1,2Nabila Y. Mahmoud and 1Ensaf M. Yassin 1Nutrition and Food Science Department, Faculty of Home Economics, Al-Azhar University, Egypt 2Department of Food Science and Nutrition, Faculty of Science, Taif University, Taif - Al-Haweiah - P.O. Box 888, ZIP code 21974, Taif, KSA Abstract: This study aimed to focus on the possible role of sesame seeds, germinated chickpea, wheat, fenugreek and water extract of fennel/anise as a rich source of phytoestrogen plants to improve menstrual disturbance for undergraduate girl students for three months. Body mass index, percent of nutrient to DRIs, food habits percent as indicator to nutritional status were examined. Menstrual problems questionnaire was collected to check period heath status. Estradiol (E2) and hemoglobin levels were tested as biochemical blood data. The collected data of body mass index percent showed high percent of ideal weight between groups followed by overweight and low percent in obesity and underweight girls. Daily intake of protein, carbohydrate and calories in most groups, increased vitamins compared to DRIs in all groups. But calcium and phosphorus percent decreased for all groups. Food habit data recorded moderate percent of all answers. Menstrual problems recorded irregular menstruation of plant groups. The best results of estradiol levels were found in fennel/anise decoction, bellila, chickpea, sesame seeds and fenugreek groups. Hemoglobin levels improved ranking of fenugreek, chickpea, sesame seeds and wheat bellila groups.