Fishing and Petroleum Interactions on Georges Bank Volume II: The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Translation Series No.1375

FISHERIES RESEARCH BOARD OF CANADA Translation Series No. 1375 Bioebenoses and biomass of benthos of the Newfoundland-Labrador region. By Ki1N. Nesis Original title: Biotsenozy i biomassa bentosa N'yufaund- • .lendskogo-Labradorskogo raiona.. From: Trudy Vsesoyuznogo Nauchno-Issledovatel'skogo •Instituta Morskogo Rybnogo Khozyaistva Okeanografii (eNIRO), 57: 453-489, 1965. Translated by the Translation Bureau(AM) Foreign Languages Division Department of the Secretary of State of Canada Fisheries Research Board of Canada • Biological Station , st. John's, Nfld 1970 75 pages typescript 'r OEPARTMENT OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE SECRÉTARIAT D'ÉTAT TRANSLATION BUREAU BUREAU DES TRADUCTIONS FOREIGN LANGUAGES DIVISION DES LANGUES DIVISION ° CANADA ÉTRANGÈRES TRANSLATED FROM - TR,ADUCTION DE INTO - EN Russian English 'AUTHOR - AUTEUR Nesis K.N. TITLE IN ENGLISH - TITRE ; ANGLAIS Biocoenoses and biomas of benthos of the Newfolindland-Labradoriregion Title . in foreign_iangnage---(tranalitarate_foreisn -ottantatere) Biotsenozy i biomassa bentosa N i yufaundlendSkogo-Labradorskogoraiona. , .ReF5RENCE IN FOREIGN ANGUA2E (NAME OF BOOK OR PUBLICATION) IN FULL. TRANSLITERATE FOREIGN CFiA,IRACTERS. • REFERENCE' EN LANGUE ETRANGERE (NOM DU LIVRE OU PUBLICATION), AU COMPLET. TRANSCRIRE EN CARACTERES PHONETIQUEL •. Trudylesesoyuznogo nauchno-iàsledovaterskogo instituta morskogo — rybnogo khozyaistva i okeanogràfii - :REFEREN CE IN ENGLISH - RÉFÉRENCE EN ANGLAIS • Trudy of the 40.1-Union Scientific-Research Instituteof Marine . Fiseriés and Oceanography. PUBLISH ER ÉDITEUR PAGE,NUMBERS IN ORIGINAL DATE OF PUBLICATION NUMEROS DES PAGES DANS DATE DE PUBLICATION . L'ORIGINAL YE.tR ISSUE.NO . 36 VOLUME ANNEE NUMERO PLACE OF PUBLICATION NUMBER OF TYPED PAGES LIEU DE PUBLICATION NOMBRE DE PAG.ES DACTY LOGRAPHIEES 1965 5 7 REQUEr IN G• DEPA RTMENT Fisheries Research Board TRANSLATION BUREAU NO. -

Fronts in the World Ocean's Large Marine Ecosystems. ICES CM 2007

- 1 - This paper can be freely cited without prior reference to the authors International Council ICES CM 2007/D:21 for the Exploration Theme Session D: Comparative Marine Ecosystem of the Sea (ICES) Structure and Function: Descriptors and Characteristics Fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems Igor M. Belkin and Peter C. Cornillon Abstract. Oceanic fronts shape marine ecosystems; therefore front mapping and characterization is one of the most important aspects of physical oceanography. Here we report on the first effort to map and describe all major fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs). Apart from a geographical review, these fronts are classified according to their origin and physical mechanisms that maintain them. This first-ever zero-order pattern of the LME fronts is based on a unique global frontal data base assembled at the University of Rhode Island. Thermal fronts were automatically derived from 12 years (1985-1996) of twice-daily satellite 9-km resolution global AVHRR SST fields with the Cayula-Cornillon front detection algorithm. These frontal maps serve as guidance in using hydrographic data to explore subsurface thermohaline fronts, whose surface thermal signatures have been mapped from space. Our most recent study of chlorophyll fronts in the Northwest Atlantic from high-resolution 1-km data (Belkin and O’Reilly, 2007) revealed a close spatial association between chlorophyll fronts and SST fronts, suggesting causative links between these two types of fronts. Keywords: Fronts; Large Marine Ecosystems; World Ocean; sea surface temperature. Igor M. Belkin: Graduate School of Oceanography, University of Rhode Island, 215 South Ferry Road, Narragansett, Rhode Island 02882, USA [tel.: +1 401 874 6533, fax: +1 874 6728, email: [email protected]]. -

An Assessment of Sea Scallop Abundance and Distribution in the Georges Bank Closed Area II - Preliminary Results

An Assessment of Sea Scallop Abundance and Distribution in the Georges Bank Closed Area II - Preliminary Results Submitted to: Sea Scallop Plan Development Team Falmouth, Massachusetts William D. DuPaul David B. Rudders Virginia Institute of Marine Science College of William and Mary Gloucester Point, VA 23062 VIMS Marine Resource Report No. 2007-3 June 27, 2007 Draft document-for Scallop PDT use only Do not circulate, copy or cite Project Summary As the spatial and temporal dynamics of marine ecosystems have recently become better understood, the concept of entirely closing or limiting activities in certain areas has gained support as a method to conserve and enhance marine resources. In the last decade, the sea scallop resource has benefited from measures that have closed specific areas to fishing effort. As a result of closures on both Georges Bank and in the mid-Atlantic region, biomass of scallops in those areas has expanded. As the time approaches for the fishery to harvest scallops from the closed areas, quality, timely and detailed stock assessment information is required for managers to make informed decisions about the re-opening. During May of 2007, an experimental cruise was conducted aboard the F/V Celtic, a commercial sea scallop vessel. At pre-determined sampling stations within the exemption area of Georges Bank Closed Area II (GBCAII) both a standard NMFS survey dredge and a commercial New Bedford style dredge were simultaneously towed. From the cruise, fine scale survey data was used to assess scallop abundance and distribution in the closed areas. The results of this study will provide additional information in support of upcoming openings of closed areas within the context of continuing sea scallop industry access to the groundfish closed areas on Georges Bank. -

Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission

Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission Interstate Fishery Management Plan for Atlantic Migratory Group Cobia ASMFC Vision: Sustainably Managing Atlantic Coastal Fisheries November 2017 Interstate Fishery Management Plan for Atlantic Migratory Group Cobia Prepared by Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission Cobia Plan Development Team Plan Development Team Members: Louis Daniel, Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, Chair Mike Schmidtke, Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission Ryan Jiorle, Virginia Marine Resources Commission Steve Poland, North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries Mike Denson, South Carolina Kathy Knowlton, Georgia Krista Shipley, Florida Deb Lambert, NMFS Kari MacLauchlin, SAFMC This Plan was prepared under the guidance of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission’s South Atlantic State/Federal Fisheries Management Board, Chaired by Jim Estes of Florida and Advisory assistance was provided by the South Atlantic Species Advisory Panel Chaired by Tom Powers of Virginia. This is a report of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission pursuant to U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award No. NA15NMF4740069. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION: The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (Commission) has developed an Interstate Fishery Management Plan (FMP) for Cobia, under the authority of the Atlantic Coastal Fisheries Cooperative Management Act (ACFCMA). Management authority for this species is from zero to three nautical miles offshore, including internal state waters, and lies with the Commission. Regulations are promulgated by the Atlantic coastal states. Responsibility for compatible management action in the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) from 3-200 miles from shore lies with the South Atlantic Fishery Management Council (SAFMC) and NOAA Fisheries under their Coastal Migratory Pelagics Fishery Management Plan (CMP FMP) under the authority of the Magnuson-Stevens Fisheries Conservation and Management Act. -

August 2011 Robert T

The Community Outlook VOL. LXII, No. 9 August 2011 Robert T. Dowling Robert T. © Published by Point Lookout Community Church, Point Lookout, Long Island, N.Y. Page 2 The Community Outlook August 2011 “A Service to the Community” than those who were more isolated. These people were less susceptible to mucous than The relationally isolated subjects. (I’m not mak- ing this up. They produced less mucous. Community This means it is literally true: Unfriendly Outlook people are snottier than friendly people.) Issued throughout the year by the God has wired us to be social beings. Point Lookout Community Church Pastor’s Outlook Whenever we live in line with the way he has P.O. Box 28 designed us to be we benefit in every way both Point Lookout, Long Island, New York One of the most fascinating statements that physically and emotionally. When we gather Jesus made is found in the Gospel of Mat- together “in His name” we then add the Brendan H. Cahill, Editor thew 18:20 where it says, “For where two spiritual component. The writer of the book Maureen Dowling O’Sullivan, or three are gathered together in my name, of Hebrews encourages the early believers Assistant Editor there am I in the midst.” I think to gather with some of the most important things they are to do when he writes this: “Let us hold Marion Lemke, Advertisements in his name is not as simple as just saying a prayer when we come together and pro- unswervingly to the hope we profess, for He Robert T. -

Optimizing the Georges Bank Scallop Fishery by Maximizing Meat Yield and Minimizing Bycatch

Optimizing the Georges Bank Scallop Fishery /; by Maximizing Meat Yield and Minimizing Bycatch Final Report Prepared for the 2017 Sea Scallop Research Set-Aside (NA17NMF4540030) October 2018 Coonamessett Farm Foundation, Inc 277 Hatchville Road East Falmouth, MA Submitted By 02536 508-356-3601 FAX 508-356-3603 Luisa Garcia, Liese Siemann, Ron Smolowitz - Coonamessett Farm [email protected] Foundation, Inc David Rudders www.cfarm.org Roxanna Smolowitz- Roger Williams University TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................... 6 INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................... 8 OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................................................. 10 GENERAL SAMPLING METHODS ....................................................................................... 10 Study area .....................................................................................................................................10 Sampling design ...........................................................................................................................11 Laboratory analysis ......................................................................................................................14 Data analysis .................................................................................................................................15 -

PDF Linkchapter

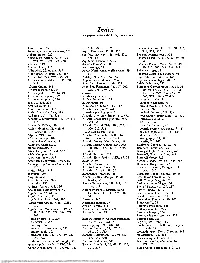

Index [Italic page numbers indicate major references] Abaco Knoll, 359 116, 304, 310, 323 Bahama Platform, 11, 329, 331, 332, Abathomphalus mayaroensis, 101 Aquia Formation, 97, 98, 124 341, 358, 360 Abbott pluton, 220 aquifers, 463, 464, 466, 468, 471, Bahama volcanic crust, 356 Abenaki Formation, 72, 74, 257, 476, 584 Bahamas basin, 3, 5, 35, 37, 39, 40, 259, 261, 369, 372, 458 Aquitaine, France, 213, 374 50 ablation, 149 Arcadia Formation, 505 Bahamas Fracture Zone, 24, 39, 40, Abyssal Plain, 445 Archaean age, 57 50, 110, 202, 349, 358, 368 Adirondack Mountains, 568 Arctic-North Atlantic rift system, 49, Bahamas Slope, 12 Afar region, Djibouti, 220, 357 50 Bahamas-Cuban Fault system, 50 Africa, 146, 229, 269, 295, 299 Ardsley, New York, 568, 577 Baja California, Mexico, 146 African continental crust, 45, 331, Argana basin, Morocco, 206 Bajocian assemblages, 20, 32 347 Argo Fan, Scotian margin, 279 Balair fault zone, 560 African Craton, 368 Argo Salt Formation, 72, 197, 200, Baltimore Canyon trough, 3, 37, 38, African margin, 45, 374 278, 366, 369, 373 40, 50, 67, 72 , 81, 101, 102, African plate, 19, 39, 44, 49 arkoses, 3 138, 139, 222, 254, 269, 360, Afro-European plate, 197 artesian aquifers, 463 366, 369, 396, 419,437 Agamenticus pluton, 220 Ashley Formation, 126 basement rocks, 74 age, 19, 208, 223 Astrerosoma, 96 carbonate deposits, 79 Agulhas Bank, 146 Atkinson Formation, 116, 117 crustal structure, 4, 5, 46 Aiken Formation, 125 Atlantic basin, 6, 9, 264 faults in, 32 Aikin, South Carolina, 515 marine physiography, 9 geologic -

Threats from Fishing and Cumulative Impacts

6.2 Adverse impacts of fishing activities under South Atlantic Council Fishery Management Plans (excerpted from Barnette 2001) All fishing has an effect on the marine environment, and therefore the associated habitat. Fishing has been identified as the most widespread human exploitative activity in the marine environment (Jennings and Kaiser 1998), as well as the major anthropogenic threat to demersal fisheries habitat on the continental shelf (Cappo et al. 1998). Fishing impacts range from the extraction of a species which skews community composition and diversity to reduction of habitat complexity through direct physical impacts of fishing gear. The nature and magnitude of the effects of fishing activities depend heavily upon the physical and biological characteristics of a specific area in question. There are strict limitations on the degree to which probable local effects can be inferred from the studies of fishing practices conducted elsewhere (North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries 1999). The extreme variability that occurs within marine habitats confounds the ability to easily evaluate habitat impacts on a regional basis. Obviously, observed impacts at coastal or nearshore sites should not be extrapolated to offshore fishing areas because of the major differences in water depth, sediment type, energy levels, and biological communities (Prena et al. 1999 ). Marine communities that have adapted to highly dynamic environmental conditions (e.g., estuaries) may not be affected as greatly as those communities that are adapted to stable environmental conditions (e.g., deep water communities). While recognizing the pitfalls that are associated with applying the results of gear impact studies from other geographical areas, due to the lack of sufficient and specific information within the Southeast Region it is necessary to review and carefully interpret all available literature in hopes of improving regional knowledge and understanding of fishery-related habitat impacts. -

WINTER FLOUNDER / Pseudopleuronectes Americanus (Walbaum 1792) / Blackback, Georges Bank Flounder, Lemon Sole, Rough Flounder / Bigelow and Schroeder 1953:276-283

WINTER FLOUNDER / Pseudopleuronectes americanus (Walbaum 1792) / Blackback, Georges Bank Flounder, Lemon Sole, Rough Flounder / Bigelow and Schroeder 1953:276-283 Description. Body oval, about two and a quarter times as long to base of caudal fin as it is wide, thick-bodied, and with a proportionately broader caudal peduncle and tail than any of the other local small flatfishes (Fig. 305). Mouth small, not gaping back to eye, lips thick and fleshy. Blind side of each jaw armed with one series of close-set incisor-like teeth. Eyed side with only a few teeth, or even toothless. Dorsal fin originates opposite forward edge of upper eye, of nearly equal height throughout its length. Anal fin highest about midway, preceded by a short, sharp spine (postabdominal bone). Pelvic fins alike on both sides of body, separated from long anal fin by a considerable gap. Gill rakers short and conical. Lateral line nearly straight, with a slight bow above pectoral fin. Scales rough on eyed side, including interorbital space; smooth on blind side in juveniles and mature females, rough in mature males when rubbed Georges Bank fish of 63.5 cm, weighing 3.6 kg. The NEFSC from caudal peduncle toward head. An occasional large adult female groundfish bottom trawl survey collected two 64-cm females, one on may also be rough ventrally. 22 October 1986 at 42°67' N, 67°32' W and a second on 15 Apri11997 at 41°01' N, 68°25'W (R. Brown, pers. comm., 25 Sept. Meristics. Dorsal fin rays 59-76; anal fin rays 44-58; pectoral fin 1998). -

Eastern U.S.-Canada Boundary Line Drawn by World Court

NOAAINMFS Developments States had argued that it was entitled to a boundary line that retained all of Georges Bank. Canada had asked for a line dividing the Bank virtually in half, leaving all of the northeastern Eastern U.S.-Canada Boundary segment under its control. The World Line Drawn by World Court Court, in essence, split the difference, setting a line that cut Georges Bank about midway between the two claims. According to the National A compromise North Atlantic vessels from both sides to return to Oceanic and Atmospheric Ad boundary line, dividing Georges Bank their respective sides of the new ministration, which has jurisdiction and its resources between the United boundary (see map). over fisheries out to 200 miles off the States of America and Canada, has The heart of the issue, which has U.S. coast, including the Georges been drawn by the World Court in been a source of dispute since 1976 Bank area, the new boundary will The Hague, Netherlands. The new when both Canada and the United make management of Atlantic boundary between New England and States extended their eastern bound fisheries, including cod and haddock, Nova Scotia gives part of the Bank to aries, was control of an area of be very complex, and will require close Canada for the first time. The issue tween l3,OOO and 18,000 square consultation with all interested par was settled on 12 October 1984 and nautical miles that included the north ties. High seas rights pertaining to the the decision was enforced as of mid eastern half of Georges Bank, one of area, such as freedom of navigation, night, 26 October 1984. -

Sea Scallops (Placopecten Magellanicus)

Methods and Materials for Aquaculture Production of Sea Scallops (Placopecten magellanicus) Dana L. Morse • Hugh S. Cowperthwaite • Nathaniel Perry • Melissa Britsch Contents Rationale and background. .1 Scallop biology . 1 Spat collection . 2 Nursery culture. 3 Growout. .4 Bottom cages . 4 Pearl nets. 5 Lantern nets. 5 Suspension cages . 6 Ear hanging. 6 Husbandry and fouling control. 7 Longline design and materials . 7 Moorings and mooring lines. 7 Longline (or backline) . 7 Tension buoys . 7 Marker buoys . 7 Compensation buoys . 8 Longline weights. 8 Site selection . 8 Economic considerations & recordkeeping . 8 Scallop products, biotoxins & public health . 8 Literature Cited. 9 Additional Reading. 9 Appendix I . 9 Example of an annual cash flow statement. 9 Acknowledgements . 9 Authors’ contact information Dana L. Morse Nathaniel Perry Maine Sea Grant and University of Maine Pine Point Oyster Company Cooperative Extension 10 Pine Ridge Road, Cape Elizabeth, ME 04107 193 Clark’s Cove Road, Walpole, ME 04573 [email protected] [email protected] Melissa Britsch Hugh S. Cowperthwaite University of Maine, Darling Marine Center Coastal Enterprises, Inc. 193 Clark’s Cove Road, Walpole, ME 04573 30 Federal Street, Brunswick, ME 04011 [email protected] [email protected] The University of Maine is an EEO/AA employer and does not discriminate on the grounds of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, transgender status, gender expression, national origin, citizenship status, age, disability, genetic information or veteran’s status in employment, education, and all other programs and activities. The following person has been designated to handle inquiries regarding non-discrimination policies: Director of Equal Opportunity, 101 North Stevens Hall, University of Maine, Orono, ME 04469-5754, 207.581.1226, TTY 711 (Maine Relay System). -

The Flounder Fishery of the Gulf of Mexico, United States: a Regional Management Plan

The Flounder Fishery of the Gulf of Mexico, United States: A Regional Management Plan ..... .. ·. Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission October 2000 Number83 GULF STATES MARINE FISHERIES COMMISSION Commissioners and Proxies Alabama Warren Triche Riley Boykin Smith Louisiana House of Representatives Alabama Department of Conservation & Natural 100 Tauzin Lane Resources Thibodaux, Louisiana 70301 64 North Union Street Montgomery, Alabama 36130-1901 Frederic L. Miller proxy: Vernon Minton P.O. Box 5098 Marine Resources Division Shreveport, Louisiana 71135-5098 P.O. Drawer 458 Gulf Shores, Alabama 36547 Mississippi Glenn H. Carpenter Walter Penry Mississippi Department of Marine Resources Alabama House of Representatives 1141 Bayview Avenue, Suite 101 12040 County Road 54 Biloxi, Mississippi 39530 Daphne, Alabama 36526 proxy: William S. “Corky” Perret Mississippi Department of Marine Resources Chris Nelson 1141 Bayview Avenue, Suite 101 Bon Secour Fisheries, Inc. Biloxi, Mississippi 39530 P.O. Box 60 Bon Secour, Alabama 36511 Billy Hewes Mississippi Senate Florida P.O. Box 2387 Allan L. Egbert Gulfport, Mississippi 39505 Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission 620 Meridian Street George Sekul Tallahassee, Florida 323299-1600 805 Beach Boulevard, #302 proxies: Ken Haddad, Director Biloxi, Mississippi 39530 Florida Marine Research Institute 100 Eighth Avenue SE Texas St. Petersburg, Florida 33701 Andrew Sansom Texas Parks & Wildlife Department Ms. Virginia Vail 4200 Smith School Road Division of Marine Resources Austin, Texas 78744 Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission proxies: Hal Osburn and Mike Ray 620 Meridian Street Texas Parks & Wildlife Department Tallahassee, Florida 32399-1600 4200 Smith School Road Austin, Texas 78744 William W. Ward 2221 Corrine Street J.E. “Buster” Brown Tampa, Florida 33605 Texas Senate P.O.