Download the Full Cyclone Debbie: Sonification Background Report Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Parks Contents

Whitsunday National Parks Contents Parks at a glance ...................................................................... 2 Lindeman Islands National Park .............................................. 16 Welcome ................................................................................... 3 Conway National Park ............................................................. 18 Be inspired ............................................................................... 3 Other top spots ...................................................................... 22 Map of the Whitsundays ........................................................... 4 Boating in the Whitsundays .................................................... 24 Plan your getaway ..................................................................... 6 Journey wisely—Be careful. Be responsible ............................. 26 Choose your adventure ............................................................. 8 Know your limits—track and trail classifications ...................... 27 Whitsunday Islands National Park ............................................. 9 Connect with Queensland National Parks ................................ 28 Whitsunday Ngaro Sea Trail .....................................................12 Table of facilities and activities .........see pages 11, 13, 17 and 23 Molle Islands National Park .................................................... 13 Parks at a glance Wheelchair access Camping Toilets Day-use area Lookout Public mooring Anchorage Swimming -

Cyclone Factsheet UPDATE

TROPICAL CYCLONES AND CLIMATE CHANGE: FACTSHEET CLIMATECOUNCIL.ORG.AU TROPICAL CYCLONES AND CLIMATE CHANGE: FACT SHEET KEY POINTS • Climate change is increasing the destructive power of tropical cyclones. o All weather events today, including tropical cyclones, are occurring in an atmosphere that is warmer, wetter, and more energetic than in the past. o It is likely that maximum windspeeds and the amount of rainfall associated with tropical cyclones is increasing. o Climate change may also be affecting many other aspects of tropical cyclone formation and behaviour, including the speed at which they intensify, the speed at which a system moves (known as translation speed), and how much strength is retained after reaching land – all factors that can render them more dangerous. o In addition, rising sea levels mean that the storm surges that accompany tropical cyclones are even more damaging. • While climate change may mean fewer tropical cyclones overall, those that do form can become more intense and costly. In other words, we are likely to see more of the really strong and destructive tropical cyclones. • A La Niña event brings an elevated tropical cyclone risk for Australia, as there are typically more tropical cyclones in the Australian region than during El Niño years. BACKGROUND Tropical cyclones, known as hurricanes in the North Atlantic and Northeast Pacific, typhoons in the Northwest Pacific, and simply as tropical cyclones in the South Pacific and Indian Oceans, are among the most destructive of extreme weather events. Many Pacific Island Countries, including Fiji, Vanuatu, Solomon Islands and Tonga, lie within the South Pacific cyclone basin. -

The Bathurst Bay Hurricane: Media, Memory and Disaster

The Bathurst Bay Hurricane: Media, Memory and Disaster Ian Bruce Townsend Bachelor of Arts (Communications) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2019 School of Historical and Philosophical Inquiry Abstract In 1899, one of the most powerful cyclones recorded struck the eastern coast of Cape York, Queensland, resulting in 298 known deaths, most of whom were foreign workers of the Thursday Island pearling fleets. Today, Australia’s deadliest cyclone is barely remembered nationally, although there is increasing interest internationally in the cyclone’s world record storm surge by scientists studying past cyclones to assess the risks of future disasters, particularly from a changing climate. The 1899 pearling fleet disaster, attributed by Queensland Government meteorologist Clement Wragge to a cyclone he named Mahina, has not until now been the subject of scholarly historical inquiry. This thesis examines the evidence, as well as the factors that influenced how the cyclone and its disaster have been remembered, reported, and studied. Personal and public archives were searched for references to, and evidence for, the event. A methodology was developed to test the credibility of documents and the evidence they contained, including the data of interest to science. Theories of narrative and memory were applied to those documents to show how and why evidence changed over time. Finally, the best evidence was used to reconstruct aspects of the event, including the fate of several communities, the cyclone’s track, and the elements that contributed to the internationally significant storm tide. The thesis concludes that powerful cultural narratives were responsible for the nation forgetting a disaster in which 96 percent of the victims were considered not to be citizens of the anticipated White Australia. -

Results for the Mackay-Whitsunday 2018 Report Card

RESULTS FOR THE MACKAY-WHITSUNDAY-ISAAC 2018 REPORT CARD ENVIRONMENTAL INDICATORS Authorship statement The Mackay-Whitsunday-Isaac Healthy Rivers to Reef Healthy Partnership (Partnership) Results for Environmental Indicators for the Mackay-Whitsunday-Isaac 2018 Report Card technical report was compiled by the Partnership’s Technical Officers, Alysha Lee and Jessica Gillespie. Substantial input was received from the Regional Report Cards Technical Working Group (TWG) members. Some content was also drawn from technical reports from earlier Mackay-Whitsunday report cards. Regional Report Cards Technical Working Group members Diane Tarte (TWG Chair July 2018 onwards) Adam Fletcher Paulina Kaniewska Nicola Stokes Richard Hunt Reinier Mann Tegan Whitehead Angus Thompson Emma Maxwell Nathan Waltham Alysha Lee Alex Carter Jessica Gillespie Michael Rasheed Carl Mitchell Glynis Orr Nyssa Henry Luke Galea Michael Holmes Eddie Jebreen David Moffatt Ken Rhode Andrew Moss Travis Sydes Lynne Powell Lyndon Llewellyn Judith Wake Nadine Marshall Donna Audas Paul Groves Chris Dench Stephen Lewis Michael Nash Chris Manning Melinda Louden Adam Folkers Acknowledgements The authors also thank Phillip Trendell, Bernie Cockayne, Bronwyn Houlden, Carol Honchin, Len McKenzie, Jamie Corfield and Matt Curnock for their technical input into various aspects of document development and/or their review of the document. Members of the Reef Independent Science Panel are also gratefully acknowledged for their advice and review of this document. Suggested citation Mackay-Whitsunday-Isaac Healthy Rivers to Reef Partnership (2019). Results for the Mackay- Whitsunday-Isaac 2018 Report Card: Environmental Indicators, Technical Report. Mackay- Whitsunday-Isaac Healthy Rivers to Reef Partnership, Mackay. This technical report was finalised and released online in November 2019. -

189930408.Pdf

© The University of Queensland and James Cook University, 2018 Published by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority ISSN: 2208-4134 Marine Monitoring Program: Annual report for inshore pesticide monitoring 2016-2017 is licensed for use under a Creative Commons By Attribution 4.0 International licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logos of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, The University of Queensland and James Cook University, any other material protected by a trademark, content supplied by third parties and any photographs. For licence conditions see: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0 This publication should be cited as: Grant, S., Thompson, K., Paxman, C., Elisei, G., Gallen C., Tracey, D., Kaserzon, S., Jiang, H., Samanipour, S. and Mueller, J. 2018, Marine Monitoring Program: Annual report for inshore pesticide monitoring 2016-2017. Report for the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, Townsville, 128 pp. A catalogue record for this publication is available from the National Library of Australia Front cover image: Turbid river plume emerging from the Russell-Mulgrave river mouth following several days of heavy rainfall in February 2015 © Dieter Tracey, 2015 DISCLAIMER While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this document are factually correct, UQ and JCU do not make any representation or give any warranty regarding the accuracy, completeness, currency or suitability for any particular purpose of the information or statements contained in this document. To the extent permitted by law UQ and JCU shall not be liable for any loss, damage, cost or expense that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of or reliance on the contents of this document. -

Horticulture Code: Growers Responsibilities P10-15

ISSUE 59 WINTER 2017 Horticulture Code: Growers responsibilities P10-15 Your source of fresh information for the fruit and vegetable industry Print post approved pp 100001181 WE CAN HELP YOU WITH GREAT DRIVEAWAY DEALS! New Toyota HiLux New Toyota CH-R New Sorento New Rio New Triton New Pajero Sport New Navara New Colorado New Trailblazer New Ranger New Escape New & Used Enquiries $ Finance Packages Service Bookings Small Business Leasing & Fleet Options Call Ian Blaikie 3000 9736 Brisbane Markets Co-ordinator motorama.com.au/brisbane-markets A4 Brisbane Markets ad Feb 17.indd 1 24/01/2017 5:31 PM CEO COMMENT HORTICULTURE CODE Brisbane Markets® is working In 2018, it will be Queensland’s turn Fresh Markets Australia (FMA) closely with its Memorandum of to bring together what is likely to hasn’t wasted any time on running Understanding partners, Bundaberg be in excess of 2,500 Australian and Horticulture Code of Conduct Fruit and Vegetable Growers New Zealand industry delegates to workshops for its 400 wholesaler and Bowen Gumlu Growers Brisbane. members around the country. Association, to assist promoting an BML, through its membership of understanding of the Code. the Central Markets Association of The 2017 legislation took effect Australia, and Brismark, through from 1 April. The wholesaling Take a look at pages 10 to 15 for its membership with Fresh Markets sector through its representative more information. Australia, have begun working with organisation, Fresh Markets DEVELOPMENT PROGRESS the 2018 Hort Connection organisers, Australia, has been working hard to Brisbane Markets® 77ha landscape AUSVEG and Produce Marketing develop a suite of Code compliant has changed enormously over the Association Australia-New Zealand, documentation which Market past 10 years since Brisbane to ensure a stellar event. -

Air Quality 10

CR Tabs_Main:Layout 1 14/5/09 3:15 PM Page 10 Air Quality 10 10 Air Quality The air quality assessment for the Caval Ridge Project has considered the potential release of dust from the site due to earth moving and mining activities associated with the construction and operation of the project. This assessment evaluates the emission sources together with the proposed mitigation measures, to determine the potential impacts at local residential communities. The air quality assessment comprises an evaluation of the local climate as well as the existing environment in relation to particulate matter. Meteorology plays an important role in the transport and dispersion of dust away from the mine site and an understanding of the local meteorological environment is crucial when assessing the impact on emissions from the mine on nearby sensitive receptors. Dispersion modelling has been performed using the DERM approved Calmet/Calpuff modelling package. A detailed emissions inventory has been established using expected activity data, in conjunction with emission factors from both the Australian National Pollutant Inventory (NPI) emission estimation manual and USEPA AP-42 emission estimation manual, which are used in the absence of site-specific data. The predicted impacts from the proposed mine operation on local air quality incorporating BMA’s proposed air quality control methods, are presented in this assessment. Mining activities for the project have been evaluated for three scenarios: Year 1, representing construction of the initial box cut in the Horse Pit, and mining operations in the Heyford Pit (for which the box cut has already been completed) Year 2, representing the first year of mining operations, in both pits, on the western side of the project site Year 20, representing mining towards the eastern side of the project site and reflecting the increasing proportion of overburden removed as the mining depth increases. -

Tourismwhitsundays.Com.Au Visitor Guide 2019/20

VISITOR GUIDE 2019/20 TOURISMWHITSUNDAYS.COM.AU HAMILTON ISLAND Remember Why hamiltonisland.com.au SAVE 10%* WHEN YOU BOOK TWO OR MORE TOURS HEART PONTOON, HARDY REEF, GREAT BARRIER REEF BARRIER GREAT REEF, HARDY PONTOON, HEART WHITEHAVEN BEACH ISLAND ESCAPE CAMIRA SAILING REEFSLEEP & HILL INLET DAY CRUISES ADVENTURE Iconic beaches, lush tropical islands, luxe resorts and the amazing Great Barrier Reef – the Whitsundays is holiday heaven. Dig your toes into the pure sand of Whitehaven Beach, snorkel amongst spectacular marine life and sleep under the stars on the Great Barrier Reef or soak up the scenery on an island-hopping day cruise – your adventure awaits with the region’s premier tour operator. TO BOOK PLEASE CONTACT CRUISE WHITSUNDAYS +61 7 4846 7000 [email protected] cruisewhitsundays.com *TERMS & CONDITIONS - ONLY ONE DISCOUNT IS ELIGIBLE PER BOOKING. DISCOUNT IS NOT AVAILABLE FOR RESORT CONNECTION SERVICES, HAMILTON ISLAND GOLF, HAMILTON ISLAND ADRENALIN, AIRLIE BEACH ATTRACTIONS OR WHITSUNDAYS CROCODILE SAFARI. THE WHITSUNDAYS, A PLACE TRULY ALIVE WITH WONDER… WHITSUNDAYS VISITOR INFORMATION CENTRE Opening late 2019 at Whitsunday Gold Coffee Plantation Bruce Hwy, Proserpine QLD 4800 +61 7 4945 3967 | [email protected] tourismwhitsundays.com.au Tourism Whitsundays acknowledge the traditional owners of this land. We pay our respects to their Elders, past and present, and Elders from other communities living in the Whitsundays today. Tourism Whitsundays would like to thank Brooke Miles - Above and Below Gallery -

SUGGESTED ITINERARIES by Rail

Discover Queensland Queensland Rail Travel - SUGGESTED ITINERARIES by Rail SAMPLE ITINERARIES Whitsunday Islands Fraser Island BRISBANE – FRASER ISLAND – WHITSUNDAYS – CAIRNS Day 1 11.00am Depart Roma Street Station, Brisbane aboard the Tilt Train in an Economy Seat. 2.40pm Arrive Maryborough West Station. Private transfer to River Heads for ferry transfer to Fraser Island (approx. 50-60 minutes). Ferry transfer departs 6.45pm daily (approx. 40 minutes). Stay at Kingfisher Bay Resort. Day 2 Join a spectacular Fraser Island and Beauty Spots Tour. Day 3 5.00pm Board ferry transfer arriving mainland terminal at 5.40pm. Private transfer from mainland terminal to Maryborough West Station (approx. 50-60 minutes). 7.29pm Depart Maryborough West Station aboard the Spirit of Queensland in a RailBed with dinner and breakfast included. Day 4 6.22am Arrive Proserpine Station and transfer with a RailBus Coach Connection to Airlie Beach (approx. 40 minutes) 7.30am Arrive Airlie Beach (six possible bus stops including Port of Airlie Cruise Whitsunday Terminal). Stay on the mainland or transfer to Daydream Island or Hamilton Island with Cruise Whitsundays. Day 5 Relax on Daydream or Hamilton Island. Day 6 Option 1 – Fly out of Hamilton Island. Option 2 – Transfer back to Airlie Beach and overnight in hotel. Day 7 5.00am Board a RailBus Coach Connection to Proserpine Station. 6.32am Depart Proserpine Station aboard the Spirit of Queensland in a Premium Economy Seat. 4.30pm Arrive Cairns Station. Discover Queensland Queensland Rail Travel - SUGGESTED ITINERARIES by Rail Fraser Island RailBed by night BRISBANE – FRASER ISLAND – CAIRNS BRISBANE – WHITSUNDAYS – CAIRNS Day 1 11.00am Depart Roma Street Station, Brisbane aboard Day 1 3.45pm Depart Roma Street Station, Brisbane aboard the Tilt Train in an Economy Seat. -

Avis Australia Commercial Vehicle Fleet and Location Guide

AVIS AUstralia COMMErcial VEHICLES FLEET SHEET UTILITIES & 4WDS 4X2 SINGLE CAB UTE | A | MPAR 4X2 DUAL CAB UTE | L | MQMD 4X4 WAGON | E | FWND • Auto/Manual • Auto/Manual • Auto/Manual • ABS • ABS • ABS SPECIAL NOTES • Dual Airbags • Dual Airbags • Dual Airbags • Radio/CD • Radio/CD • Radio/CD The vehicles featured here should • Power Steering • Power Steering • Power Steering be used as a guide only. Dimensions, carrying capacities and accessories Tray: Tray: are nominal and vary from location 2.3m (L), 1.8m (W) 1.5m (L), 1.5m (W), 1.1m (wheelarch), tub/styleside to location. All vehicles and optional 4X4 SINGLE CAB UTE | B | MPBD 4X4 DUAL CAB UTE | D | MQND 4X4 DUAL CAB UTE CANOPY | Z | IQBN extras are subject to availability. • Auto/Manual • Auto/Manual • Auto/Manual For full details including prices, vehicle • ABS • ABS • ABS availability and options, please visit • Dual Airbags • Dual Airbags • Dual Airbags • Radio/CD • Radio/CD • Radio/CD www.avis.com.au, call 1800 141 000 • Power Steering • Power Steering • Power Steering or contact your nearest Avis location. Tray: Tray: Tray: 1.5m (L), 1.5m (W), 2.3m (L), 1.8m (W) 1.8m (L), 1.8m (W) 0.9m (H) lockable canopy VANS & BUSES DELIVERY VAN | C | IKAD 12 SEATER BUS | W | GVAD LARGE BUS | K | PVAD • Air Con • Air Con • Air Con • Cargo Barrier • Tow Bar • Tow Bar • Car Licence • Car Licence • LR Licence Specs: 5m3 2.9m (L), 1.5m (W), Specs: 12 People Specs: 1.1m (wheelarch) including Driver 20-25 People HITop VAN | H | SKAD 4.2M MovING VAN | F | FKAD 6.4M MovING VAN | S | PKAD 7.3M VAN | V | PQMR • Air Con • Air Con • Air Con • Air Con • Power Steering • Ramp/Lift • Ramp/Lift • Ramp/Lift • Car Licence • Car Licence • MR Licence • MR Licence Specs: 3.7m (L), 1.75m (W), Specs: Specs: Specs: 19m3, 4.2m (L), 34m3, 6.4m (L), 42m3, 7.3m (L), 1.9m (H), between 2.1m (W), 2.1m (H), 2.3m (W), 2.3m (H), 2.4m (W), 2.4m (H), wheel arch 1.35m (L) up to 3 pallets up to 10 pallets up to 12 pallets *Minimum specs. -

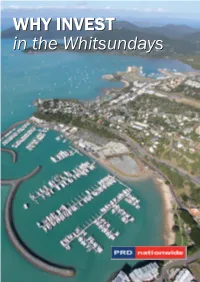

Why Invest in the Whitsundays

WHYWHY INVESTINVEST inin thethe WhitsundaysWhitsundays Whitsunday Region Profile Why invest in the Whitsundays Location Airlie Beach is just one square kilometre of ultimate real estate that is the most exclusive waterfront lifestyle precinct on the planet. With the township book ended by two world class marinas and appointed with a range of cosmopolitan dining and fashion options, the Airlie Beach lifestyle is the perfect foundation. The township is well connected to the 74 Whitsunday Islands, 8 of which are resort islands and the remaining islands are protected National Parks. More than half of the 2600km2 Shire is classified as National Park, ensuring the retention of the area’s natural beauty. Located just 25km inland is Proserpine, home to the region’s hospital, railway station, sugar mill and primary airport. Bowen,situated on the north-eastern coast of the region, is known for its award winning beaches and delicious mangoes. Finally Collinsville, found 87km south-west of Bowen, lies within the resource rich Bowen Basin and is home to several mines. Quality of Life The results of an extensive survey conducted by Tourism and Events Queensland in 2013 revealed that 92% of residents love living here and 58% of residents would not live anywhere else. More than 85% of residents were born elsewhere in Australia, and more than 60% of residents stay for 10 years or more after relocating to the area. Of the residents surveyed, a large majority identified that the tourism industry results in many positive impacts for the area, including more interesting things to do, employment opportunities, events and festivals, improved facilities, increased local pride and greater cultural diversity. -

Product Update

Hello valued trade partners, Sending you some warm sunshine from the Whitsundays, which is currently experiencing 24 degrees Celsius winter days, with clear blue skies and tropical turquoise waters. Tourism Whitsundays would like to take the opportunity to thank you all for your ongoing support over the past few months. Your commitment and assistance to the Whitsundays is greatly appreciated. The Whitsundays truly shines in winter, with the region attracting humpback whales, who head north to give birth in the warm tropical waters. Sighting these majestic mammals and their calves is a memorable, awe-inspiring experience and one that people talk about for many years afterwards. It is possible to experience a whale encounter in the Whitsundays at any time from July through to September – some come as early as late June – and many passengers on sailing vessels and day trips have this unexpected delight while out on the water. There is no better place than the Whitsundays to escape the winter blues! Should you have any questions about the region or if you would like to talk to the team about future trade partnerships, then please reach out to us here at Tourism Whitsundays. We look forward to delivering an unforgettable Whitsundays experience to your clients. Warm Whitsunday wishes, Tourism Whitsundays Trade Team Product Update New Boutique Hotel + Bar & Grill coming soon to the Whitsundays - Freedom Shores + Northerlies Beach Bar & Grill Freedom Shores has been designed to capture the natural surrounds of the beach, water and lush Whitsundays tropical forests. Be immersed in a destination like no other. Freedom Shores® - Boutique Hotel accommodation with a twist, plus Northerlies Beach Bar and Grill® - with a view you won’t want to leave.