Allegany Council House Notes – Jennifer Walkowski

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Weekly Lists for 1997

National Register of Historic Places 1997 Weekly Lists WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 12/23/96 THROUGH 12/27/96 .................................... 3 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 12/30/96 THROUGH 1/03/97 ...................................... 5 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 1/06/97 THROUGH 1/10/97 ........................................ 8 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 1/13/97 THROUGH 1/17/97 ...................................... 12 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 1/20/97 THROUGH 1/25/97 ...................................... 14 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 1/27/97 THROUGH 1/31/97 ...................................... 16 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 2/03/97 THROUGH 2/07/97 ...................................... 19 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 2/10/97 THROUGH 2/14/97 ...................................... 21 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 2/17/97 THROUGH 2/21/97 ...................................... 25 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 2/24/97 THROUGH 2/28/97 ...................................... 28 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 3/03/97 THROUGH 3/08/97 ...................................... 32 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 3/10/97 THROUGH 3/14/97 ...................................... 34 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 3/17/97 THROUGH 3/21/97 ...................................... 36 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 3/24/97 THROUGH 3/28/97 ...................................... 39 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 3/31/97 THROUGH 4/04/97 ...................................... 41 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 4/07/97 THROUGH 4/11/97 ...................................... 43 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 4/14/97 THROUGH 4/18/97 ..................................... -

Sedgwick-Highland-James Preservation District Guidelines Pertain to the Exterior Treatment of Historic Properties

Guidelines & Standards Sedgwick-Highland-James Preservation District Syracuse, New York City of Syracuse Landmark Preservation Board 2004 Guidelines & Standards Sedgwick-Highland-James Preservation District Syracuse, New York This publication was made possible through a grant from the Certified Local Government program. The Certified Local Government program and this publication are financed in part with federal funds provided by the National Park Service, Department of the Interior, and administered by the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation. However, the contents and opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior. Regulations of the U.S. Department of the Interior strictly prohibit unlawful discrimination in departmental federally assisted programs on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, or handicap. Any person who believes he or she has been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility operated by a recipient of federal assistance should write to: Director, Equal Opportunity Program, U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, P.O. Box 37127, Washington, D.C. 20013-7127. Publication by Randall T. Crawford, 1998 Revised by Syracuse Landmark Preservation Board, 2003 Table of Contents 1. Introduction……………………………………………………………… 1-1 2. The Design Review Process………………………………………….. 2-1 Design Review…………………………………………………………. 2-1 Certificate of Appropriateness……………………………………… 2-2 Application Guidelines………………………………………………. 2-2 Application Process at a Glance…………………………………… 2-3 Repairs and In-Kind Replacement……………………………….. 2-3 3. Description, History, and Significance………………………….. 3-1 Description and History……………………………………………. 3-1 Significance……………………………………………………………. 3-2 Map……………………………………………………………………… 3-4 4. Residential Architectural Styles………………………………….. 4-1 Italianate………………………………………………………………. 4-1 Colonial Revival………………………………………………………. -

National Register of Historic Places - Onondaga County Sites

Field Office Technical Guide Section II – Natural Resources Information – Cultural Resources Information Page - 51 NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES - ONONDAGA COUNTY SITES The following information is taken from: http://www.nationalregisterofhistoricplaces.com/ny/Onondaga/state2.html NEW YORK - Onondaga County ALVORD HOUSE (ADDED 1976 - BUILDING - #76001257) N OF SYRACUSE ON BERWICK RD., SYRACUSE Historic Significance: Event, Information Potential Area of Significance: Historic - Non-Aboriginal, Agriculture Cultural Affiliation: American,rural Period of Significance: 1825-1849 Owner: Local Gov't Historic Function: Domestic Historic Sub-function: Single Dwelling Current Function: Landscape, Vacant/Not In Use Current Sub-function: Park AMOS BLOCK (ADDED 1978 - BUILDING - #78001890) 210--216 W. WATER ST., SYRACUSE Historic Significance: Event, Architecture/Engineering Architect, builder, or engineer: Silsbee,Joseph Lyman Architectural Style: Romanesque Area of Significance: Commerce, Transportation, Architecture Period of Significance: 1875-1899 Owner: Private , Local Gov't Historic Function: Commerce/Trade Historic Sub-function: Business Current Function: Vacant/Not In Use U.S. Department of Agriculture New York Natural Resources Conservation Service August 2002 Field Office Technical Guide Section II – Natural Resources Information – Cultural Resources Information Page - 52 ARMORY SQUARE HISTORIC DISTRICT (ADDED 1984 - DISTRICT - #84002816) ALSO KNOWN AS SEE ALSO:LOEW BUILDING S. CLINTON, S. FRANKLIN, WALTON, W. FAYETTE, AND W. JEFFERSON -

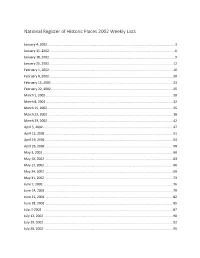

National Register of Historic Places Weekly Lists for 2002

National Register of Historic Places 2002 Weekly Lists January 4, 2002 ............................................................................................................................................. 3 January 11, 2002 ........................................................................................................................................... 6 January 18, 2002 ........................................................................................................................................... 9 January 25, 2002 ......................................................................................................................................... 12 February 1, 2002 ......................................................................................................................................... 16 February 8, 2002 ......................................................................................................................................... 20 February 15, 2002 ....................................................................................................................................... 23 February 22, 2002 ....................................................................................................................................... 25 March 1, 2002 ............................................................................................................................................. 28 March 8, 2002 ............................................................................................................................................ -

History of L'pool, Syr, Danforth Lodges

A History of LLiivveerrppooooll--SSyyrraaccuussee LLooddggee NNoo.. 501 Free & Accepted Masons Liverpool, New York 1824 to 2000 Compiled by R.’.W.’. Gary L. Heinmiller Area 11 Historian Grand Lodge of Free & Accepted Masons of the State of New York Historian Liverpool - Syracuse Lodge No. 501 Liverpool, New York 1995 - 2010 Leonidas Lodge No. 381 4 Jun 1824 - 5 Jun 1834 --------- Liverpool Lodge No. 525 5 Jun1863 - 2 May 1994 Liverpool Temple Dedicated 6 Aug 1918 ---------- Syracuse Lodge No. 484 9 Jun 1826 - 5 Jun 1835 Syracuse Lodge No. 102 23 Jul 1844 - 5 Jul 1860 Syracuse Lodge No. 501 5 Jul 1860 - 2 May 1994 ---------- Danforth Lodge No 957 19 May 1919 - 15 May 1985 ---------- Liverpool Syracuse 501 Chartered 2 May 1994 1 A History of Liverpool-Syracuse Lodge No. 501 F&AM Liverpool, New York 1824 to 1995 Early History of Onondaga County, Syracuse & Liverpool The area now known as Onondaga County took its name from the Central Nation of the great Iroquois Confederacy, the Onondagas. It was here that the Council Fire was then, and is to this day, kept. A chronology of the birth of the Onondaga County of today is as follows: 1610 - Dutch first settled in New York, then called New Netherlands. 1638 - The vast territory west of Albany (Fort Orange) was called "Terra Incognita". 1615 - Samuel de Champlain contacted the domain of the Iroquois. 1651 - Radisson visited the Onondaga area. 1654 - Father Simon Le Moyne visited the Onondaga area. 1655 - Chaumonot and Dablon founded a mission and fort near what is now Liverpool. 1683 - The English gained supremacy over the Dutch settlements in the Colony of New York and subdivided it into twelve counties, one of which was Albany County. -

Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 18 / Tuesday, January 28, 1997 / Notices

4076 Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 18 / Tuesday, January 28, 1997 / Notices 6-months notice, during a legislative session, facilities including roads, pipelines, Dated: January 22, 1997. of his intention to submit the petition; or power lines, compressor stations and G. William Lamb, 3. The state legislature implements a law water disposal facilities. State Director, Utah. or regulation permitting and encouraging the development of coalbed methane. The BLM also proposes to approve [FR Doc. 97±2001 Filed 1±27±97; 8:45 am] development of natural gas within the BILLING CODE 4310±DQ±M Since the State of Illinois has met the project area and approve individual condition for removal from the List of drilling applications and right of way Affected States by passing a resolution [CO±030±07±1820±00±1784] authorizations. requesting removal, the State of Illinois is officially removed from the List of Possible Alternatives Southwest Resource Advisory Council Affected States. Meetings The EIS will analyze the Proposed FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: AGENCY: Bureau of Land Management, Action and the No-Action Alternative. David R. Stewart, Chief, Branch of Interior. Resources Planning and Protection, Other alternatives may include various well spacing options and resource ACTION: Notice; Resource Advisory Bureau of Land Management, Eastern Council meetings. States, 7450 Boston Boulevard, protection alternatives. Springfield, Virginia 22153, or Anticipated Issues SUMMARY: In accordance with the telephone (703) 440±1728; or Charles W. Federal Advisory Committee Act (5 Byrer, U.S. Department of Energy, 3610 Potential issues include air quality, USC), notice is hereby given that the Collins Ferry Road, Morgantown, West social and economic impacts, ground Southwest Resource Advisory Council Virginia 26507, or telephone (304) 285± water, water disposal, wildlife, and (Southwest RAC) will meet on 4547. -

Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 18 / Tuesday, January 28, 1997 / Notices

Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 18 / Tuesday, January 28, 1997 / Notices 4077 the number of persons wishing to make Montezuma County NEW YORK oral statements, a per-person time limit Wrightsman House, 209 Bauer Ave., Mancos, Albany County may be established by the Montrose 97000045 Slingerlands, Albert, House, 36 Bridge St., District Manager. Routt County Slingerlands, 97000068 Summary minutes for Council meetings are maintained in the DawsonÐCarpenter Ranch, 13250 W. US 40, Columbia County Hayden vicinity, 97000047 Montrose District Office and are Church of Our Saviour, NY 22, near jct. with available for public inspection and FLORIDA US 20, Hamlet of Lebanon Springs, New reproduction during regular business Pasco County Lebanon vicinity, 97000067 hours within thirty (30) days following Baker, Samuel, House, 5744 Moog Rd., Elfers, Jefferson County each meeting. 97000052 Tracy Farm (Orleans MPS), E. side of Wilder Dated: January 21, 1997. Sarasota County Rd., S of jct. with Overbluff Rd., Orleans, Mark W. Stiles, 97000066 Casa Del Mar, 25 S. Washington Dr., Sarasota, District Manager. 97000051 Onondaga County [FR Doc. 97±1949 Filed 1±27±97; 8:45 am] GEORGIA Ashton House (Architecture of Ward BILLING CODE 4310±JB±P Wellington Ward in Syracuse MPS), 301 Dooly County Salt Springs Rd., Syracuse, 97000089 Byrom, William H., House, Main St., near the Blanchard House (Architecture of Ward National Park Service jct. of GA 90 and the Seaboard Coast RR, Wellington Ward in Syracuse MPS), 329 Dooly, 97000053 Westcott St., Syracuse, 97000094 National -

Jrr"!T^R.Oir PI Apf-^ This Form Is for Use in Documenting

(June 1991) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR RECEIVED 2280 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE „,„„*».i******"""1-*"*™"***"" 1 """ " ""nJa*1 NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES MULTIPLE PROPERTY DOCUMENTATION FORM MfiT> ._,.RFTISTER . jrr"!T^r.oirU! nl^lurti^ PIr^nvt-tj apf-^ This form is for use in documenting multiple property -^--:-- »i/LCi-{j\nri-. or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Comp le Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. [x] New Submission [ ] Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Architecture of Ward Wellington Ward in Syracuse, New York, 1908-1932 B. Associated Historic Contexts___________________________________________ (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period of each.) Architecture of Ward Wellington Ward in Syracuse, New York, 1908-1932 C. Form Prepared by name/title Richard Carlson/consultant organization Private consultant date September 11, 1996 street & number 200 East Upland Rd. telephone (607) 257-7631 city or town Ithaca__________ state New York zip code 14850 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. -

• a Survey of • Scottholm Syracuse, New York

• A SURVEY OF • SCOTTHOLM SYRACUSE, NEW YORK 2010 Cornell University CRP-5610 Historic Preservation Historic Preservation Planning Program Planning Workshop: Surveys For the City of Syracuse Dear Residents: We members of the Cornell Historic Preservation Planning Pro- gram are excited to share with you the cultural resource sur- vey we have been conducting of the Scottholm Tract. Over the past three months, students enrolled in the CRP5610 Preserva- tion Planning Workshop have been researching a section of your neighborhood; you may have seen us walking around, taking pictures, measuring sidewalks and the distance between trees, or talking to you about the history of Scottholm. This survey is a joint effort between the City of Syracuse and Cornell’s Historic Preservation Planning Program, conducted so that the city can have a better understanding of its historic resources in order to enhance future planning in the area. We have created this booklet for you to see what we have been doing, and some of what we found. Thank you for the warm welcome you have extended to us over the course of the semester, and for allowing us to survey your neighborhood. Students Katherine Coffield Jessica Follman Mahyar Hadighi Meghan Hayes Katherine Kaliszewski Donald Johnson Christiana Limniatis William Marzella Gregory Prichard Jonathon Rusch Jessica Stevenson Ryann Wolf Faculty Jeffrey Chusid Katelyn Wright A History Of SCOTTHOLM From the opening of the Erie Canal to the beginning of the Great Depression, Syracuse experienced a century of nearly unabated progress and prosperity. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the city enjoyed a vibrant downtown, a booming population, and a healthy mix of industrial and commercial pursuits. -

Oha Research Center Reading Room Subject Finding Aid

1 OHA RESEARCH CENTER READING ROOM SUBJECT FINDING AID The primary research collection of the Onondaga Historical Association is the Vertical File collection, which is contained in over 100 file cabinets and has been gathered over the course of the past century. The Vertical File Collection of the Onondaga Historical Association’s Research Center has five main divisions or series: Biographical/Genealogical Block Image Subject Town each of which has numerous subdivisions or sub-series. BIOGRAPHICAL / GENEALOGICAL FILES The Biographical Files contain newspaper clippings, research notes, photographs, ephemera, genealogical information, and other material on specific individuals or families. These are arranged alphabetically. In many instances there are separate files for individuals while in other cases there are general files for a particular surname. Note: there is a separate listing of Genealogical Titles in this guide, which is a list of printed/published genealogies. BLOCK FILES The Block Files contain material primarily pertaining to the Syracuse City blocks and wards. There are separate block files for Salina and Geddes Blocks, which pertain to areas pre-dating the incorporation of the City of Syracuse in 1848. The files contain newspaper clippings, photographs, sections from the Sanborn Fire Insurance Atlases from 1894 through 1950 (not consistently for each and every block), and other materials relating to the structures and land usage patterns within a limited area including Syracuse. The easiest point of access to the Block Files is the reference set of 1957 Sanborn Atlases. 1 2 Note: there is additional information contained in the general Syracuse files on Subdivisions and there are separate files on some Syracuse City Streets. -

Berkeley Park Historic District Syracuse, New York

Guidelines & Standards Berkeley Park Historic District Syracuse, New York Guidelines & Standards Berkeley Park Historic District Syracuse, New York Syracuse Landmark Preservation Board, 2006 Table of Contents 1. Introduction……………………………………………………………..… 1-1 2. The Design Review Process…………………………………………... 2-1 Design Review………………………………………………………..…. 2-1 Certificate of Appropriateness…………………………………….… 2-2 Application Guidelines……………………………………………….. 2-2 Application Process at a Glance………………………………….… 2-3 Repair and In-Kind Replacement…………………..………………. 2-4 Certificate of Appropriateness Application………….…………….2-5 3. Description, History, and Significance………………………..….. 3-1 Description & History……………………………………………..….. 3-1 Significance……………………………………………………………... 3-2 Map…………………………………………………………………….…. 3-3 4. Residential Architectural Styles…………………………………..… 4-1 Colonial Revival………………………………………………………... 4-1 Tudor Revival…………………..……………………………………….. 4-1 French and Spanish Eclectic…….……………………………….… 4-1 Craftsman Bungalow………………………………………………….. 4-1 Pictorial Guide…………………………………………………………..4-3 5. The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation-A Framework for Judging the Appropriateness of Changes to Historic Properties………..…. 5-1 6. Guidelines……………………………………………………………..…… 6-1 Awnings………………………………………………………………….. 6-1 Demolition……………………………………………………………….. 6-2 Demolition or Partial Demolition of Buildings…………… 6-2 Exterior Wall Surfaces………………………………………………… 6-2 Repair and Replacement……………………………………… 6-3 Exterior Wood Cladding………………………………. 6-3 Historic Stucco…………………………………………. -

Federal Register/Vol. 67, No. 8/Friday, January 11, 2002/Notices

Federal Register / Vol. 67, No. 8 / Friday, January 11, 2002 / Notices 1501 comments should be submitted by Fremont County forwarded by United States Postal January 28, 2002. Rector, Jason and Elizabeth Baylor, Service, to the National Register of House,2174 Bluff Rd.,Thurman, 01001542 Historic Places, National Park Service, Erika Martin Seibert, KANSAS 1849 C St. NW, NC400, Washington, DC Acting, Keeper of the National Register. 20240; by all other carriers, National Arkansas Atchison County Register of Historic Places, National Earhart, Amelia, Historic District,115– Park Service, 800 N. Capitol St.NW, Clark County 125,200–227,302–315,318,324 2nd St, 203– Suite 400, Washington DC 20002; or by Arkadelphia Boy Scout Hut, 8th 305 North Ter, 124,200,300 3rdSt, and fax, 202–343–1836. Written or faxed St.,Arkadelphia, 01001526 205,112 and 224 Santa Fe St.,Atchison, 01001543 comments should be submitted by Hot Spring County January 28, 2002. Cowley County Rockport Cemetery,US 270,Rockport, Carol D. Shull, 01001527 St. John’s Lutheran College Girls Dormitory,6th Ave and Gary St.,Winfield, Keeper of the National Registerof Historic Perry County 01001544 Places. Hawks Schoolhouse, Co. Rd. 7,Ava, NEVADA 01001528 CONNECTICUT Churchill County Hartford County Connecticut Churchill County Jail,10 W Williams Clark Farm Tenant House Site,Address New London County Ave.,Fallon, 01001546 Hazen Store,00 Reno Highway,Hazen, Restricted,East Granby, 01001554. Slater Library and Fanning Annex,26 Main 01001547 St.,Griswold, 01001529 GEORGIA SOUTH CAROLINA Tolland County Fulton County Aiken County Spotswood Hall,(West Paces Ferry Road Captain Nathan Hale Monument,120 Lake MRA)555 Argonne Dr., NW,Atlanta, St.,Coventry, 01001531 Zubly Cemetery,Forrest Dr.,Beech Island, 01001548 01001556.