Botanist Interior 43.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

28. GALIUM Linnaeus, Sp. Pl. 1: 105. 1753

Fl. China 19: 104–141. 2011. 28. GALIUM Linnaeus, Sp. Pl. 1: 105. 1753. 拉拉藤属 la la teng shu Chen Tao (陈涛); Friedrich Ehrendorfer Subshrubs to perennial or annual herbs. Stems often weak and clambering, often notably prickly or “sticky” (i.e., retrorsely aculeolate, “velcro-like”). Raphides present. Leaves opposite, mostly with leaflike stipules in whorls of 4, 6, or more, usually sessile or occasionally petiolate, without domatia, abaxial epidermis sometimes punctate- to striate-glandular, mostly with 1 main nerve, occasionally triplinerved or palmately veined; stipules interpetiolar and usually leaflike, sometimes reduced. Inflorescences mostly terminal and axillary (sometimes only axillary), thyrsoid to paniculiform or subcapitate, cymes several to many flowered or in- frequently reduced to 1 flower, pedunculate to sessile, bracteate or bracts reduced especially on higher order axes [or bracts some- times leaflike and involucral], bracteoles at pedicels lacking. Flowers mostly bisexual and monomorphic, hermaphroditic, sometimes unisexual, andromonoecious, occasionally polygamo-dioecious or dioecious, pedicellate to sessile, usually quite small. Calyx with limb nearly always reduced to absent; hypanthium portion fused with ovary. Corolla white, yellow, yellow-green, green, more rarely pink, red, dark red, or purple, rotate to occasionally campanulate or broadly funnelform; tube sometimes so reduced as to give appearance of free petals, glabrous inside; lobes (3 or)4(or occasionally 5), valvate in bud. Stamens (3 or)4(or occasionally 5), inserted on corolla tube near base, exserted; filaments developed to ± reduced; anthers dorsifixed. Inferior ovary 2-celled, ± didymous, ovoid, ellipsoid, or globose, smooth, papillose, tuberculate, or with hooked or rarely straight trichomes, 1 erect and axile ovule in each cell; stigmas 2-lobed, exserted. -

Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science

Comparison of Groundlayer and Shrublayer Communities in Full Canopy and Light Gap Areas of Hoot Woods, Owen County, Indiana Rebecca A. Strait and Marion T. Jackson Department of Life Sciences Indiana State University Terre Haute, Indiana 47809 AND D. Brian Abrell Indiana Department of Natural Resources Indianapolis, Indiana 46204 Introduction Hoot Woods is a 64-acre (25.9-ha) old-growth beech-maple dominated forest located in Owen County, Indiana, about 3 miles northwest of the village of Freedom. The tract occupies a gentle east-facing slope which closely approximates the average environment for that region. Predominate soils are residual Wellston and Muskingum silt loams (35-70% slopes) and Zanesville silt loam (12-18% slope) derived in sandstone and shale (Owen County Soil Survey Report). National Natural Landmark designation was awarded the stand several years ago in recognition of its overall high quality and lack of disturbance. Forest composition and stand dynamics of Hoot Woods have been the focus of several studies (Petty and Lindsey, 1961; Jackson and Allen, 1967; Donselman, 1973; Levenson, 1973; Williamson, 1975; Abrell and Jackson, 1977; and Jackson and Abrell, 1977). A 10.87-acre (4.40-ha) area within the best section of the stand was fully censused for forest trees and all stems > 4.0 inches (10 cm) dbh mapped at a 1:33 scale during the summer of 1965 (Jackson and Allen, 1967). An additional 5.43-acre (2.20-ha) ad- joining area was mapped during the decade interval follow-up study by Abrell and Jackson (1977) bringing the total area under consideration to 16.30 acres (6.60-ha). -

Complete Iowa Plant Species List

!PLANTCO FLORISTIC QUALITY ASSESSMENT TECHNIQUE: IOWA DATABASE This list has been modified from it's origional version which can be found on the following website: http://www.public.iastate.edu/~herbarium/Cofcons.xls IA CofC SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME PHYSIOGNOMY W Wet 9 Abies balsamea Balsam fir TREE FACW * ABUTILON THEOPHRASTI Buttonweed A-FORB 4 FACU- 4 Acalypha gracilens Slender three-seeded mercury A-FORB 5 UPL 3 Acalypha ostryifolia Three-seeded mercury A-FORB 5 UPL 6 Acalypha rhomboidea Three-seeded mercury A-FORB 3 FACU 0 Acalypha virginica Three-seeded mercury A-FORB 3 FACU * ACER GINNALA Amur maple TREE 5 UPL 0 Acer negundo Box elder TREE -2 FACW- 5 Acer nigrum Black maple TREE 5 UPL * Acer rubrum Red maple TREE 0 FAC 1 Acer saccharinum Silver maple TREE -3 FACW 5 Acer saccharum Sugar maple TREE 3 FACU 10 Acer spicatum Mountain maple TREE FACU* 0 Achillea millefolium lanulosa Western yarrow P-FORB 3 FACU 10 Aconitum noveboracense Northern wild monkshood P-FORB 8 Acorus calamus Sweetflag P-FORB -5 OBL 7 Actaea pachypoda White baneberry P-FORB 5 UPL 7 Actaea rubra Red baneberry P-FORB 5 UPL 7 Adiantum pedatum Northern maidenhair fern FERN 1 FAC- * ADLUMIA FUNGOSA Allegheny vine B-FORB 5 UPL 10 Adoxa moschatellina Moschatel P-FORB 0 FAC * AEGILOPS CYLINDRICA Goat grass A-GRASS 5 UPL 4 Aesculus glabra Ohio buckeye TREE -1 FAC+ * AESCULUS HIPPOCASTANUM Horse chestnut TREE 5 UPL 10 Agalinis aspera Rough false foxglove A-FORB 5 UPL 10 Agalinis gattingeri Round-stemmed false foxglove A-FORB 5 UPL 8 Agalinis paupercula False foxglove -

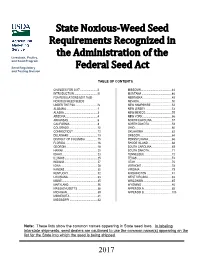

State Noxious-Weed Seed Requirements Recognized in the Administration of the Federal Seed Act

State Noxious-Weed Seed Requirements Recognized in the Administration of the Livestock, Poultry, and Seed Program Seed Regulatory Federal Seed Act and Testing Division TABLE OF CONTENTS CHANGES FOR 2017 ........................ II MISSOURI ........................................... 44 INTRODUCTION ................................. III MONTANA .......................................... 46 FSA REGULATIONS §201.16(B) NEBRASKA ......................................... 48 NOXIOUS-WEED SEEDS NEVADA .............................................. 50 UNDER THE FSA ............................... IV NEW HAMPSHIRE ............................. 52 ALABAMA ............................................ 1 NEW JERSEY ..................................... 53 ALASKA ............................................... 3 NEW MEXICO ..................................... 55 ARIZONA ............................................. 4 NEW YORK ......................................... 56 ARKANSAS ......................................... 6 NORTH CAROLINA ............................ 57 CALIFORNIA ....................................... 8 NORTH DAKOTA ............................... 59 COLORADO ........................................ 10 OHIO .................................................... 60 CONNECTICUT .................................. 12 OKLAHOMA ........................................ 62 DELAWARE ........................................ 13 OREGON............................................. 64 DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ................. 15 PENNSYLVANIA................................ -

Crooked-Stem Aster,Symphyotrichum Prenanthoides

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Crooked-stem Aster Symphyotrichum prenanthoides in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2012 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2012. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Crooked-stem Aster Symphyotrichum prenanthoides in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. ix + 33 pp. (www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default_e.cfm). Previous report(s): COSEWIC. 2002. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the crooked-stem aster Symphyotrichum prenanthoides in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 16 pp. Zhang, J.J., D.E. Stephenson, J.C. Semple and M.J. Oldham. 1999. COSEWIC status report on the crooked-stem aster Symphyotrichum prenanthoides in Canada, in COSEWIC assessment and status report on the crooked-stem aster Symphyotrichum prenanthoides in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-16 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Allan G. Harris and Robert F. Foster for writing the status report on the Crooked-stem Aster, Symphyotrichum prenanthoides, in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada. This report was overseen and edited by Jeannette Whitton and Erich Haber, Co- chairs of the COSEWIC Vascular Plants Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur L’aster fausse-prenanthe (Symphyotrichum prenanthoides) au Canada. -

Vascular Plant Species of the Cayuga Region of New York State F

Vascular Plant Species of the Cayuga Region of New York State F. Robert Wesley, Sana Gardescu, and P. L. Marks © 2008 Cornell Plantations (first author); Dept. of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology (other authors), Cornell University, Ithaca NY 14853. This species list is available online. Search for "Wesley" at: <http://ecommons.library.cornell.edu/browse-author> For more details and a summary of the patterns found in the data, see the Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society for an article based on this species list, published in 2008, entitled "The vascular plant diversity of the Finger Lakes region of central New York State: changes in the 1800s and 1900s," by P.L. Marks, F.R. Wesley, & S. Gardescu. For a link to the Journal's 2008 issues and abstracts, go to: <http://www.torreybotanical.org/journal.html> The following list of vascular plants includes native and non-native species that occur in a multi-county area in central New York State (see map below). We have called this the "Cayuga Region," as it includes the "Cayuga Quadrangle" of the flora of Clausen (1949) and the "Cayuga Lake Basin" of earlier floras (Dudley 1886, Wiegand & Eames 1926). A single set of modern species concepts was used, to correct for variations in nomenclature among the floras. Species found only under cultivation are not included. SPECIES NAMES are in alphabetical order, within major group. NATIVE/NOT is with respect to the Cayuga Region. For non-natives, WHEN HERE is the year by which the species had first established i the region, based on the floras of Dudley (1886), Wiegand & Eames (1926), Clausen (1949), and Wesley (2005; unpublished). -

Checklist Flora of the Former Carden Township, City of Kawartha Lakes, on 2016

Hairy Beardtongue (Penstemon hirsutus) Checklist Flora of the Former Carden Township, City of Kawartha Lakes, ON 2016 Compiled by Dale Leadbeater and Anne Barbour © 2016 Leadbeater and Barbour All Rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or database, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, without written permission of the authors. Produced with financial assistance from The Couchiching Conservancy. The City of Kawartha Lakes Flora Project is sponsored by the Kawartha Field Naturalists based in Fenelon Falls, Ontario. In 2008, information about plants in CKL was scattered and scarce. At the urging of Michael Oldham, Biologist at the Natural Heritage Information Centre at the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Dale Leadbeater and Anne Barbour formed a committee with goals to: • Generate a list of species found in CKL and their distribution, vouchered by specimens to be housed at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, making them available for future study by the scientific community; • Improve understanding of natural heritage systems in the CKL; • Provide insight into changes in the local plant communities as a result of pressures from introduced species, climate change and population growth; and, • Publish the findings of the project . Over eight years, more than 200 volunteers and landowners collected almost 2000 voucher specimens, with the permission of landowners. Over 10,000 observations and literature records have been databased. The project has documented 150 new species of which 60 are introduced, 90 are native and one species that had never been reported in Ontario to date. -

The Rubiaceae of Ohio

THE RUBIACEAE OF OHIO EDWARD J. P. HAUSER2 Department of Biological Sciences, Kent State University, Kent, Ohio Eight genera and twenty-seven species, of which six are rare in their distribu- tion, are recognized in this study as constituting a part of Ohio's flora, Galium, represented by fifteen species, is the largest genus. Five other genera, Asperula, Cephalanthus, Mitchella, Sherardia, and Spermacoce, consist of a single species. Asperula odorata L., Diodia virginiana L., and Galium palustre L., are new reports for the state. Typically members of the Rubiaceae in Ohio are herbs with the exception of Cephalanthus occidentalis L., a woody shrub, and Mitchella repens L., an evergreen, trailing vine. In this paper data pertinent to the range, habitat, and distribution of Ohio's species of the Rubiaceae are given. The information was compiled from my examination of approximately 2000 herbarium specimens obtained from seven herbaria located within the state, those of Kent State University, Miami Uni- versity, Oberlin College, The Ohio State University, Ohio Wesleyan University, and University of Cincinnati. Limited collecting and observations in the field during the summers of 1959 through 1962 supplemented herbarium work. In the systematic treatment, dichotomous keys are constructed to the genera and species occurring in Ohio. Following the species name, colloquial names of frequent usage and synonyms as indicated in current floristic manuals are listed. A general statement of the habitat as compiled from labels on herbarium specimens and personal observations is given for each species, as well as a statement of its frequency of occurrence and range in Ohio. An indication of the flowering time follows this information. -

Vascular Flora of a Southern Appalachian Fen and Floodplain Complex

CASTANEA 69(2): 116–124. JUNE 2004 Vascular Flora of a Southern Appalachian Fen and Floodplain Complex 1 1 2 ROBERT J. WARREN II, *J.DAN PITTILLO, and IRENE M. ROSSELL 1Department of Biology, Western Carolina University, Cullowhee, North Carolina 28723-9646; 2Environmental Studies Department, University of North Carolina at Asheville, Asheville, North Carolina 28804-3299 ABSTRACT A survey of vascular flora was completed at wetland sites in the Tulula Creek floodplain in Graham County, North Carolina as part of a comprehensive ecological study. The vegetation survey was conducted in forested and unforested fen and floodplain wetlands in 1994 and 2001, and in a forested floodplain wetland in 2001 in order to document plant species occurring in these rare mountain habitats. A total of 107 taxa representing 52 families were identified. More than 66% of the taxa also have been reported in other non- alluvial wetlands in the region; about 31% of the taxa identified in the Tulula Creek wetland complex have been reported in non-alluvial wetlands in West Virginia and about 12% have been reported in the non- alluvial wetlands of northeastern United States and adjacent Canada. This paper documented the vascular plant communities within this rare wetland complex before intensive stream restoration began in 2001. INTRODUCTION Wetland plant communities in the Southern Blue Ridge Province are uncommon ecological islands within an expansive temperate deciduous forest; they often contain plant species that do not occur in the surrounding terrestrial and fluvial habitats (Weakley and Schafale 1994). Non-alluvial southern Appalachian wetlands are found in every mountain county in North Carolina (Weakley and Schafale 1994), yet they are infrequent ecosystems that cover less than one percent of the land area (Pittillo 1994). -

Great Lakes Coastal Wetlands Monitoring Plan

Great Lakes Coastal Wetlands Monitoring Plan Developed by the Great Lakes Coastal Wetlands Consortium, A project of the Great Lakes Commission Funded by the United States Environmental Protection Agency Great Lakes National Program Office March 2008 This page intentionally blank. Table of Contents Editors ...........................................................................................................................................................8 Authors..........................................................................................................................................................8 Acknowledgments .......................................................................................................................................10 Executive Summary .....................................................................................................................................12 Statistical Design.....................................................................................................................................13 Chemical/Physical and Land Use/Cover Measurements.........................................................................13 Vegetation Community Indicators ..........................................................................................................14 Invertebrate Community Indicators ........................................................................................................14 Fish Community Indicators......................................................................................................................15